★★★★☆

The Courtauld welcomes Peter Doig’ first show since moving back to London from Trinidad after 20 years away, with 12 paintings and a selection of etchings.

Header Image: Peter Doig, House of Music, (Soca Boat), (2019-23) © Prudence Cuming Associates

Having your work exhibited at the Courtauld as a living artist is no small feat. It’s the first time they have done so since a £57 million revamp two years ago, and a distinction last bestowed to Frank Auerbach in 2009 (one of the works from that show now hangs next to Modigliani in the permanent collection). With that in mind, it’s no wonder that here, and now, one of Britain’s beloved sons gets his flowers.

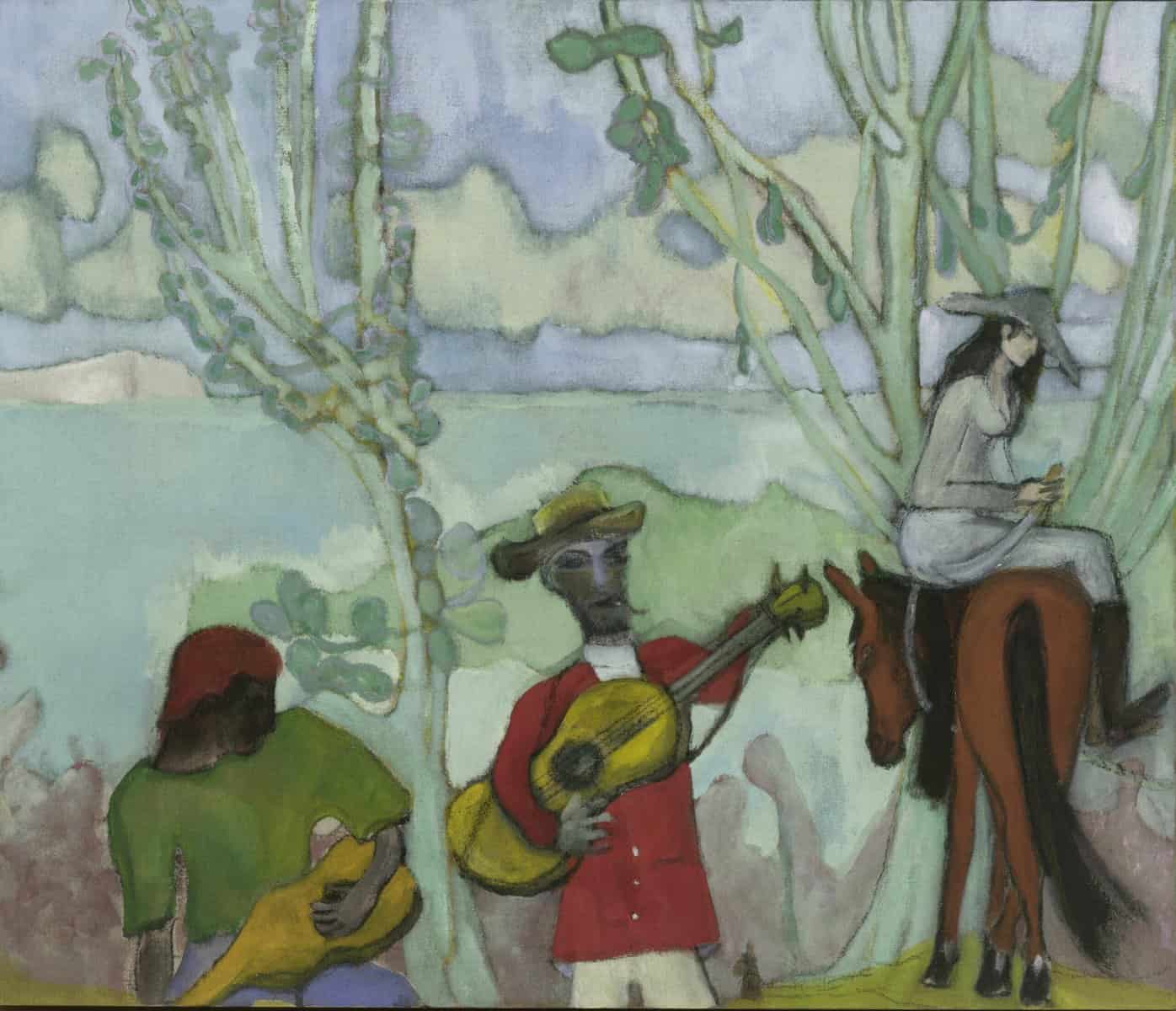

Usually revered for his landscapes, Peter Doig shifts his focus to figures as a cast of melancholic avatars takes centre stage in these compositions, like in Music (2 Trees) where calypso singers croon against the coastline’s plaintive tones of the turquoise and emerald, and Night Studio, a daunting self-portrait that dominates the entrance to the show.

‘Music (2 Trees)’, (2019) by Peter Doig © Jochen Littkemann

Artistic Heritage and Influence: Gauguin, Cézanne, and Beyond

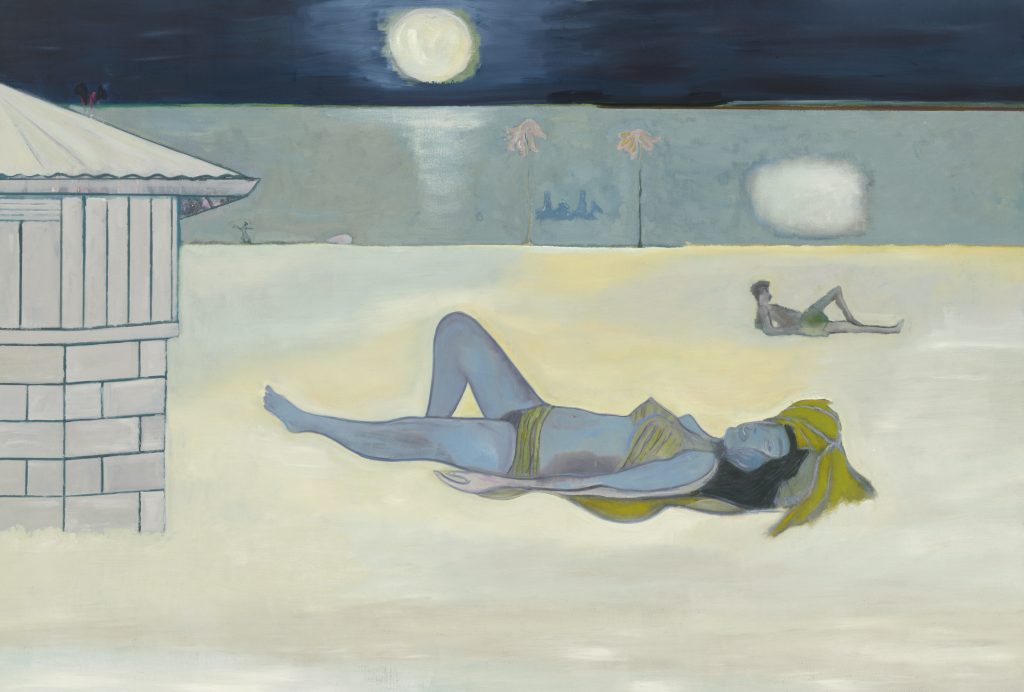

Nestled in the corner of the Gallery’s top floor, the show benefits from a break from the ‘white cube’ as it’s prefaced by the works of Impressionist and Modernist masters – a rich aperitif. We see Cézanne’s presence in Night Bathers and Bather, though these are more hangovers: the analogy is like a half-remembered conversation.

READ MORE: Keita’s Rembrandt: Osaka to Toronto and back again

Instead, Doig finds more in tune with Gauguin. While both artists draw from the deep spiritual wells of their respective adopted islands – the former’s decidedly less sordid than the latter’s in Tahiti – it’s their shared turn to the subconscious where they find understanding; Doig’s declaration in the show’s opening tombstone that “I never try to create real spaces – only painted spaces” evokes Gauguin’s urging of Van Gogh in Arles to ‘compose from memory’.

‘Night Bathers’ (2011-2019) by Peter Doig © Peter Doig

The show leans into this discourse between artist and artistic heritage, with the agitprop press release stating that: “Visitors will be able to consider Doig’s contemporary works in the light of paintings by earlier artists in The Courtauld’s collection that are important for him, such as those by Cézanne, Gauguin, Manet, Monet, Pissarro and Van Gogh. The exhibition will explore how Doig recasts and reinvents traditions and practices of painting to create his own highly distinctive works.”

How the present interacts with the past always offer an accessible springboard for curation, though it can risk straddling exhibition with baggage. Heavy lies the contextual crown – it’s one that the artist acknowledged in trepidation of his work being shown at the Courtauld: “I’m going to get a beating”.

Despite his deference, Doig stands tall among these titans of painting. Negotiating friction between imagination and figuration, the works exude a quiet magnetism that cut through his forefathers.

‘Canal’, (2023) by Peter Doig © Prudence Cuming Associates

Canal is a strong example of this, where we see a return to his memorable compositional vehicles of dew drop trees and acid-wash verdure. We’re unsure where we stand in time, with winter to the left and autumn to the right. At the same time, a muted palette and figural fuzziness engender a detached broodiness that bleeds through this temporal neverland.

Few do the natural world quite like Doig. With Alpinist, the show’s centrepiece, insight is granted into this connection: against an immense tundra climbs a harlequin skier, the diamonds of his snowsuit tesselate through forests of fir that prick against the landscape and ascend into the towering Matterhorn. The curators again ask us to think of Cézanne (you almost want to tell them to fuck off at this point), but the artist’s Instagram reveals a nod to Harry Styles's recent Swarovski jumpsuit he wore to the Grammys. Nae bad a case for art imitating life.

‘Alpinist’, (2019-2022) by Peter Doig © Peter Doig

A Two-Fold Re-emergence: Doig’s Artistic Process and Unfinished Works

This exhibition marks a two-fold re-emergence for Doig. As rumours bubbled through a pandemic of discontent of a rift’s deepening fractures with his long-term gallery Michael Werner, his wife, Parinaz Mogadassi, confirmed in February that they had parted ways. Artnews detective Annie Armstrong revealed that Werner had been left out of much of the exhibition’s planning, and one could almost tell. Notably, most of the works had been painted over several years, many of which were only completed this year.

There are two ways of looking at this: a recognition of the artistic practice and the careful consideration that Doig places on rendering nostalgia’s layered synapses. The other, more cynical, is the impression of unfinished work. In an interview with the Guardian a week before the show’s opening, Doig admitted that with a deadline looming, he was rushing to finish painting. The levitating instruments in Music Shop and the half-baked tonal modelling in House of Music (Soca Boat) indicate that he was rushed. Some of the works, when considered individually, come across as slightly premature. Whether by the Courtauld looking for a contemporary champion or Doig’s own desire to brandish his new-found bachelorhood.

View this post on Instagram

Navigating the Art Market: Doig’s Journey Towards Autonomy

Doig’s decision to run alone is perhaps more understandable when one factors in a long-standing aversion to his commercial success. Intense market speculation led to a £20 million auction record in 2021, while primary market sales regularly go into seven figures. This has always been a source of discomfort – “You get seen as a different kind of artist, one whose work is of interest only to the mega-rich,” he told the New Yorker. Money breeds opportunists, and Doig has only managed to end a decade-long legal battle to clear his name of a misattributed painting.

Doig is not alone in looking for a better deal. This shift away from conventional representation forms part of a wider phenomenon. He joins a growing list of artists rejecting exclusive partnerships with galleries, hammering out better commission rates, or simply selling the works themselves (Zuckerman’s algorithm flatters me by targeting ads for Doig’s limited prints sold through the Courtauld, priced at £3000). With these developments, the traditional parameters of the primary market are being weathered away; last year saw Christie’s and Sotheby’s get a feel for an integrated selling field by opening initiatives for artists to consign directly to auction.

Watching where Doig goes professionally and artistically will be fascinating, and it will bear considerable relevance to the art world. Though, in any case, it’s a rare joy to see his works outside of private collections and off the walls of an auction preview.

Peter Doig at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, runs to 29 May.