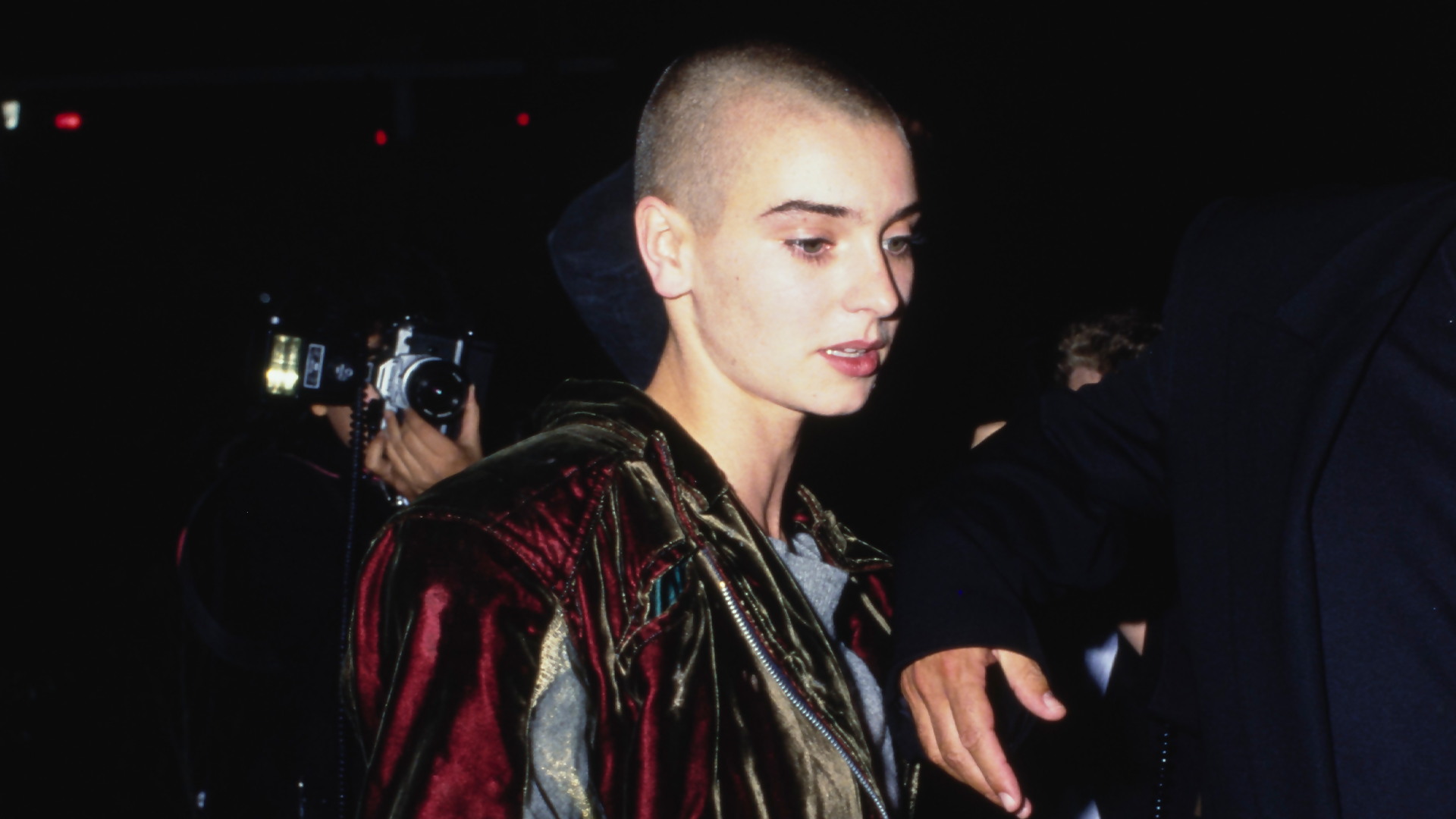

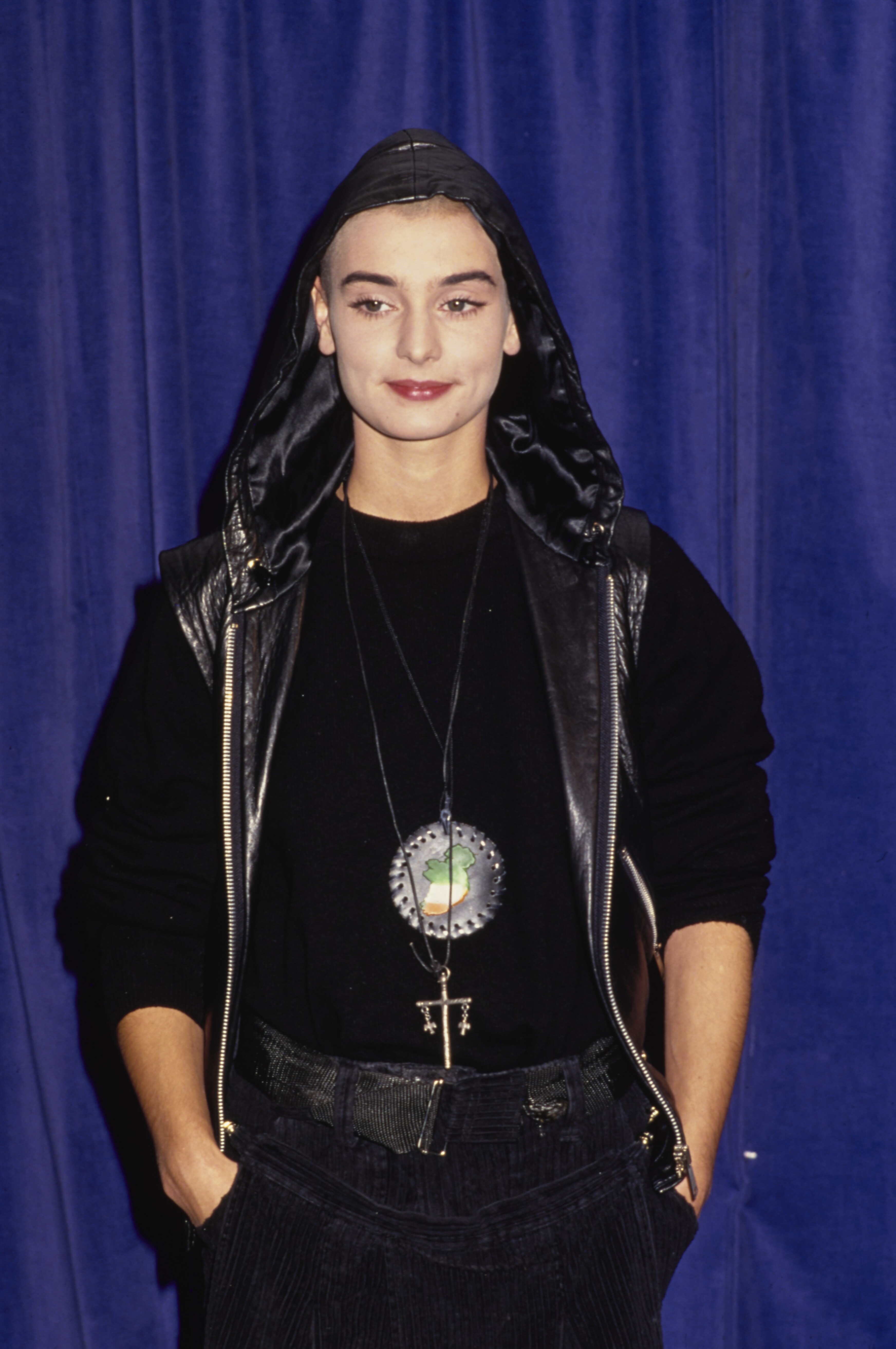

“I think an artist’s job is to be themselves at any cost,” Sinéad O’Connor said in her firm but tender Irish lilt during a 2002 BBC interview. Certainly, from the moment her shaved-headed, fists-in-the-air defiance was emblazoned on the cover of her 1987 debut album Lion and the Cobra, it set a prescient image of an artist who would be ruthlessly themselves.

Of course, many will no doubt best remember O’Connor for the huge, lovelorn hit ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’, which was one of the best-selling singles of the ‘90s. It shot the singer to worldwide fame and ensured she remained a household name. But other moments of fame (some of infamy) would cloud the singer’s colourful life. Indeed, she would express herself – whatever the cost.

Here, we look at the challenging earlier years that shaped Sinéad O’Connor and the thread of uncompromising character that ran throughout her life and its key milestones.

Photo: Vinnie Zuffante

How her troubled childhood led her to a life of music

O’Connor’s 2021 memoir Rememberings paints an almost unimaginable picture of child cruelty. It describes how her mother, Marie (nee O’Grady), would regularly strip her naked and beat her, often with an “obsession” for destroying the young child’s reproductive organs. On the day O’Connor’s father left the family home, when the youngster was eight, the mother would lock her and her two siblings out of the family home.

At the age of 15, amid the abuse, O’Connor was placed under the care of a Magdalene asylum in Dublin for truancy and shoplifting – the latter of which she was actively encouraged to perpetrate by her mother. Although life there remained difficult, with O’Connor disciplined in other ways, it was at Magdalene where a nun gave O’Connor her first guitar. This, it would transpire, set O’Connor’s path in a different direction.

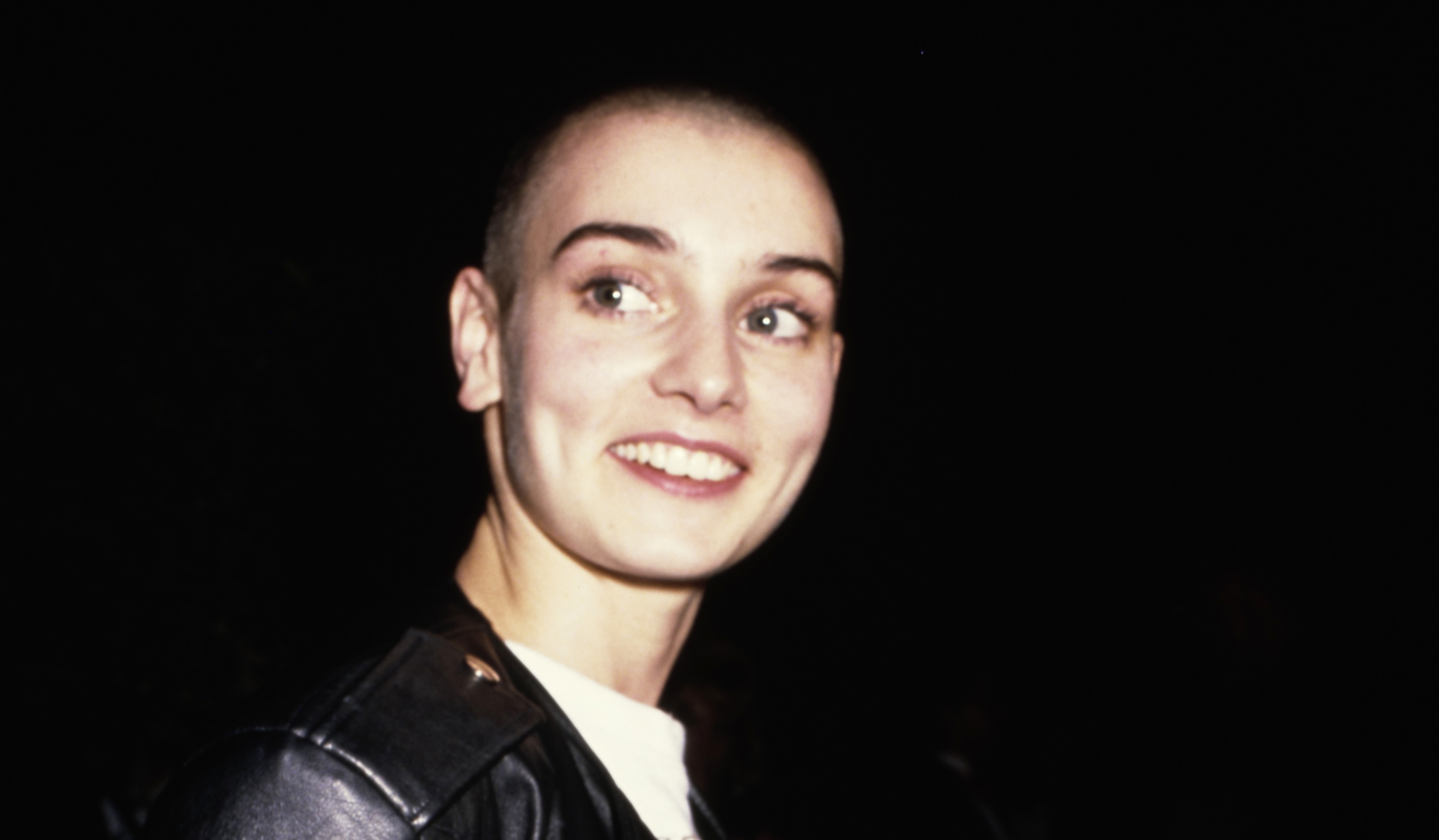

Photo: Vinnie Zuffante

By the time O’Connor’s mother died in a car crash at the age of 45, the 18-year-old had finally found something she could hold onto; with music being a place that nurtured her soul, unlike she had received as a child and allowed her to be the non-conformist she was, unlike the rigid practices she was forced to maintain at the Dublin asylum.

With influences ranging from Bob Dylan to Siouxsie And The Banshees, O’Connor took to the streets of Dublin to busk and by 1985, with her fledgling distinct vocal range and sense of adventure, she signed to Ensign Records.

Nothing Compares 2 U

Hardly a soul in music can claim to overshadow Prince – even on one occasion. But, arguably, the commercial and artistic peak of O’Connor’s career would do just that. Originally written by Prince for his Paisley Park Records side-project The Family, the track would feature on the funk band’s only album: their eponymous 1985 LP.

Fachtna O’Kelly, O’Connor’s manager, is believed to have first suggested she cover the track. O’Connor and her producer Nellee Hooper would take the tune some five years later and give it a completely new arrangement, transforming it from a woozy rock number into an F-major power ballad and, in the process, a chart-topping phenomenon. (Prince would later engage in something of an act of reclamation, adding his duet version of the track with Rosie Gaines – perhaps having seen the success a female voice could bring to it – to his 1993 collection The Hits).

Photo: Scott Gries

Of course, there are no objective answers as to what makes a hit a hit – something which falls into sharp focus when a cover achieves more acclaim than its original. But there is something undeniable about the depth of genuine feeling with which O’Connor approaches the song.

In Rememberings, O’Connor explained that she was thinking of her mum and their fraught relationship, notably on the line “All the flowers that you planted mama / In the back yard / All died when you went away.” It’s almost at this exact moment, in fact, on the video’s accompanying video, where you see the Irish singer crying. Those are real tears and emotions stretching beyond the often overdone emotions of power ballads.

The substance and lyrics of the track have been told time and time before with its clear-cut appraisal of heartbreak. But O’Connor’s version has stood the test of time by having that ingredient you can neither buy nor concoct in the studio: authenticity.

This resonated with people around the world. The song topped the charts in some 17 countries, was crowned “the number one World Single” for the year by Billboard and sold more than 3.5 million copies in its first year. O’Connor, already a known artist since the release of her debut three years earlier, had now been catapulted to international stardom.

Sinéad O’Connor protests sexual abuse of minors in the church, ripping up a photo of The Pope Live on SNL — earning a lifetime ban from the show.

The following decades would reveal just how pervasive the abuse was. Rest in power. pic.twitter.com/QwjP1lEQ4t

— Kaivan Shroff (@KaivanShroff) July 26, 2023

Ripping up the image of the Pope – and the backlash

But almost immediately from the moment she found herself under the global spotlight, the core tenet of her character – her uncompromising sense of self – began to rub up against the demands placed on someone when they become more than a person, but a cog in an industry. By August 1990, she provoked the ire of Americans by reportedly refusing to play a gig in New Jersey that had played, as is customary, the US national anthem ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ before the show.

The backlash was near-instantaneous. Some radio stations banned her songs. People destroyed her CDs at protests. The New York State Senator Nicholas Spano called for a boycott of her shows. In one of the first of many public disputes with known figures, none other than Frank Sinatra had criticised her, reportedly advising her to at least leave the country or, at most, “have her a** kicked.”

That episode would be merely a sign of things to come. If you want to remain in favour of the American people, then it’s best not to cause consternation around the national anthem and religion (and guns, of course). Yet O’Connor wouldn’t have a problem with expressing her views publicly on either. In 1992, she demonstrated she really did do as she wanted when on Saturday Night Live!, at the end of an a cappella performance of Bob Marley’s ‘War’, she held up a photo of Pope John Paul II and ripped it into pieces before saying the words: “Fight the real enemy.”

Her act, which instantly stunned the TV audience (the SNL producer Lorne Michaels immediately ordered the applause sign not to be used), had been aimed at the sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church. Given what we know now about the Catholic church and its big, dark secret, it might seem odd to consider the immense backlash the singer faced. But O’Connor was detrimentally ahead of her time, only to be vindicated some nine years later when the pope publicly admitted the abuse at the hands of the religious institution.

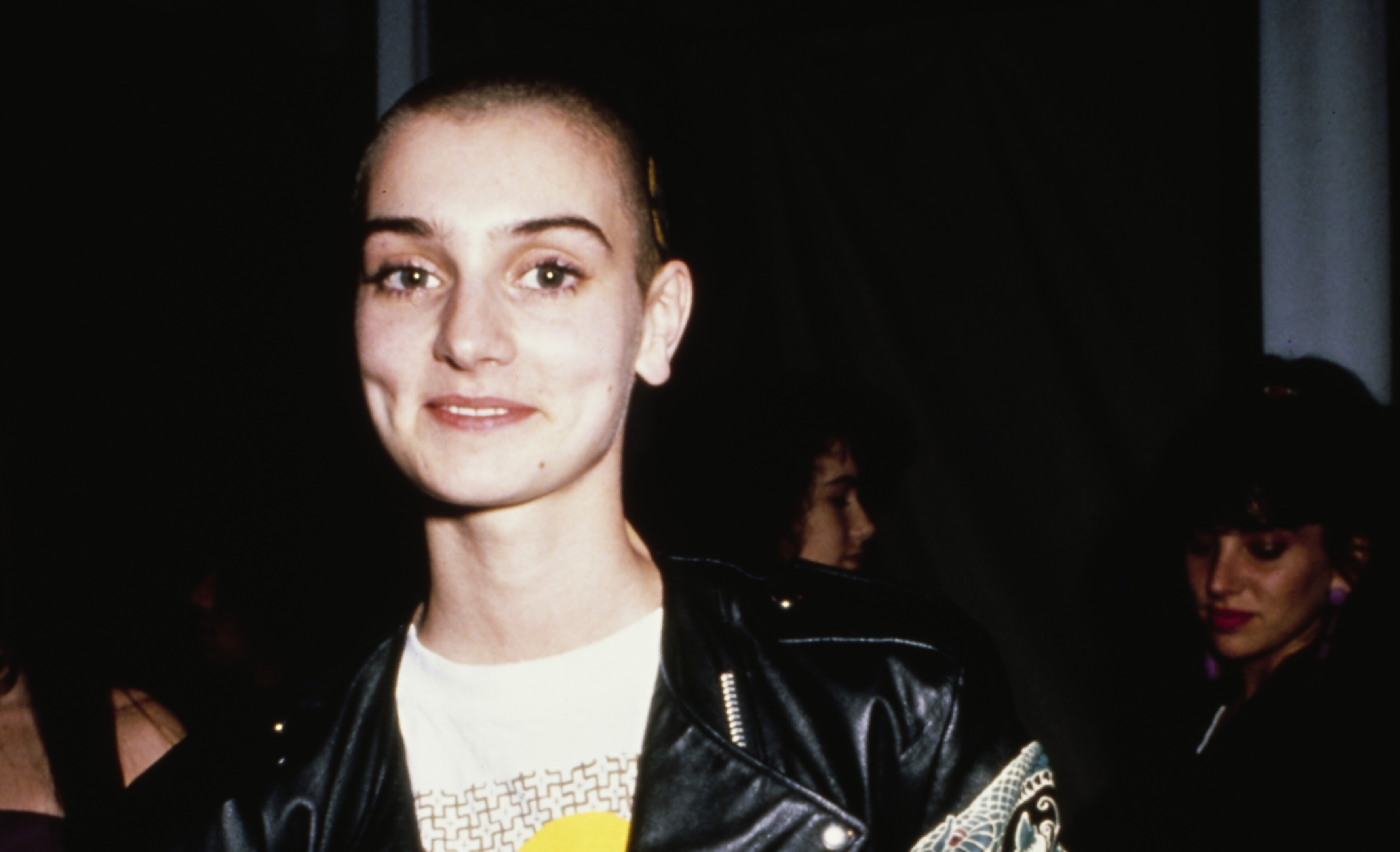

Photo: Vinnie Zuffante

The response was brutal and unrelenting. As O’Connor would say herself some years later, it became fashionable to denounce her. The New York Daily News branded her a “Holy Terror”, and NBC banned her for life, while over the pond, The Sun labelled her “Sinéad, She Devil!”. Catholic-raised Madonna, meanwhile – no stranger to controversy herself – would publicly chastise her.

The most face-to-face example of the outcry O’Connor had caused arrived just two weeks later when she was on the line-up for a 30th-anniversary tribute concert to her hero Bob Dylan. Introduced to the stage by Kris Kristofferson, she was met by a sea of boos. Her response, in turn, demonstrated her character, at one point halting her band from playing only so she could soak up and face down the animosity.

After gazing into the distance, she doubled down on her convictions, bursting into another a-cappella song with ‘War’ (incidentally, another made popular by Marley), adding another vocal criticism after “And until the ignoble and unhappy regime” of “Child abuse, child abuse.” Seen in the light of today, this was an act of immense bravery; O’Connor was defiant onstage, but her subsequent burst into tears offstage, hugged by Kristofferson, is a reminder that a human still lay beneath.

She would never have another Number 1 record in the US, following her 1990 LP I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, the parent album of ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’, but ripping the image of the Pope in protest against child sexual abuse was an act of liberation that was worth it; in Rememberings, O’Connor would write poignantly of this episode, in terms that says more about the limitations of free expression when subject to the whims of the public eye.

“A lot of people say or think that tearing up the Pope’s photo derailed my career. That’s not how I feel about it,” she wrote. “I feel that having a No. 1 record derailed my career and my tearing the photo put me back on the right track.” Once again, this subversion of what’s considered the greater deed was a belief held on account of O’Connor being truly herself – whatever the cost.

The many public disputes

Few things could be more significant than angering Sinatra and Madonna, but O’Connor would continue to have many public feuds. Arguably the most recognisable of them arrived in 2013, in response to Miley Cyrus, who had credited the Irish singer and the ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ video as an inspiration for her provocative video of ‘Wrecking Ball’. O’Connor didn’t take this as a compliment and instead penned an open letter, warning the young actress-turned-pop star, “you will obscure your talent by allowing yourself to be pimped, whether it’s the music business or yourself doing the pimping.”

These no-nonsense words, even if prefaced as being “said in the spirit of motherliness and with love”, in turn, saw a sharp response from Cyrus, who compared O’Connor with the troubled actress Amanda Bynes, who had been undergoing psychiatric treatment at the time. This came during a period when O’Connor herself had been suffering from bipolar disorder, and the Irish singer would threaten legal action and ask for a public apology. Whilst in this instance, it would be Cyrus who was more readily criticised for her rather childish response (she was just 20 at the time), it nonetheless evoked a sense of O’Connor being the target of public shaming that had long been a theme of her career.

In 2016, too, O’Connor was the subject of a lawsuit that would indeed materialise and for which she would be the defendant. After Prince’s death in 2016, O’Connor wrote her own tribute to the man who had penned her defining tune; only, she also wrote that the late, great icon was also a “long time hard drug user” who “got his drugs over the decades” from US talk show host Arsenio Hall.

The result, unsurprisingly, amounted to a $5 million (£3.8 million) defamation lawsuit from Hall and his reps – something made even less surprising by the singer’s add-ons: “I do not like drugs killing musicians. And I do not like Arsenio Hall. He can suck my dick. That is if he isn’t too busy sucking someone else’s dick.”

O’Connor’s retraction some 300 days later, both deleting all the posts and apologising for “insinuating that Arsenio had something to do with Prince’s death” was a rarity in the world of O’Connor – a climbdown invoked by the threat of a multi-million-dollar payout (perhaps there is, after all, some degree of cost).

Converting (or “reverting”) to Islam

In more recent years, the shaved-head image of O’Connor was replaced by one wearing a hijab, a woman whose name wasn’t Sinéad O’Connor but Shuhada’ Sadaqat. On 19 October 2018, the singer announced she had converted to Islam – or “reverted”, as she would term it in interviews, citing the religion’s central text, The Quran. She wrote: “This is to announce that I am proud to have become a Muslim. This is the natural conclusion of any intelligent theologian’s journey. All scripture study leads to Islam. Which makes all other scriptures redundant.”

Whilst this marked the public pronouncement, O’Connor’s decision had actually arrived a year earlier, but she had kept it a secret as she felt it unnecessary to justify or explain. Certainly, O’Connor would have been wary of the scrutiny placed on her religious beliefs. Not only did her symbolic act of ripping up an image of the pope some 25 years prior pit her against the Catholic Church, but in 1999 she stirred yet more trouble among religious figures when she was ordained as a priest and renamed Mother Bernadette Mary after a ceremony held by the breakaway Latin Tridentine church in Lourdes.

The Catholic Church – still likely incensed by her sacrilegious act on live TV earlier in the decade – denied the ordination and didn’t see it as anything other than “bizarre and absurd.” One prominent dissident priest, Pat Buckley, even decried that an act of simony (purchasing a sacrament) had been committed on account of her £IR150,000 to priest Bishop Michael Cox who ordained her – even if the money was pledged to set up a healing centre for Ireland’s travelling community in County Offaly.

O’Connor’s varied religious experiences even once amounted to a keen interest in Rastafarianism – holding it in high regard for its intersection between activism, music and spirituality. (Her first encounter with Rastafarian musicians came when she was 17 and had visited London to see a friend who ran open mic sessions on Portobello Road and who had a radio station called Dread Broadcasting). This was most evidenced in her work through her 2005 Throw Down Your Arms LP – her first reggae album, the genre emblematic of the wider Rastafari movement.

Retirement from music – and then rescinding

In 2021, following the release of Rememberings, O’Connor would go as far as to announce her retirement from music, the thing she held so dear. In giving interviews for the book, she had requested that the press be mindful of the traumatic aspects the memoirs divulge. Only, being the media, these requests fell largely on deaf ears, certainly in O’Connor’s eyes. One particular review of the book from The Telegraph, which described her as “the crazy woman in pop’s attic” – a line repeated on BBC Woman’s Hour – irked O’Connor more than most.

As a result, she announced her retirement, writing in typically plainspoken terms: “I’ve gotten older and I’m tired. So it’s time for me to hang up my nipple tassels, having truly given my all.”

Yet after seeing the support from fans, she said her initial take was merely a “knee-jerk” reaction to the media, which had made her the subject of international ridicule on several occasions. Consequently, she retracted her retirement and committed herself to her 2022 tour dates. But as with almost everything on O’Connor’s journey, an unexpected turn – this time in the form of the most tragic circumstances a person can experience – lay awaiting.

At the start of last year, two days after being reported missing, Shane O’Connor – the third youngest of his mother’s children – was found dead by the Gardaí in Bray, County Wicklow. He died from suicide by hanging.

Some days after the tragedy, Sinead herself was hospitalised after an unverified Twitter account linked to hers had sent some troubling messages, including: “There is no point living without him. Everything I touch, I ruin. I only stayed for him. And now he’s gone.” She would later seek to allay fears over the posts and announced she was seeking help.

Photo: Gaye Gerard

On 26 July, aged 56, Sinéad O’Connor was found unresponsive at her London home. The police are not treating her death as suspicious. She leaves behind her a legacy that extends beyond the immense power of ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ and its beautiful doe-eyed music video – an ode to humanity at its most raw. Her 1987 debut alone, The Lion and the Cobra, was one of the most striking of its time, venturing into a pop sound that few had mustered prior.

Whilst tributes have inevitably poured in, Morrissey has notably slammed many of them as superficial, criticising people who “hadn’t the guts to support her when she was alive.” Whatever you might think of the The Smiths frontman – who has a well-documented non-conformist streak himself – he has a point. The life of Sinead O’Connor, who stood up for what she believed in and expressed herself as she saw fit, reminds us of that virtue some of the very best teach us when they leave: to be a little kinder, a little less quick to judge, and to do so during one’s life.