Architecture, as a practice, has always been a bit of a chimera. The Ancient Greeks placed it among the constructive arts, far below the loftier pursuits of music, poetry, and theatre. The Roman architect Vitruvius helped its case a little, in the 1st century BC, by insisting that architecture was an intellectual endeavour, founded on knowledge of pure science, and not merely the work of hard labour.

And yet, something was still missing, something that the other arts had, something intangible that architecture wanted to cement beneath its keystone; something called ‘poetics’. Enter the eighteenth century, the age of enlightenment, which would change the fortunes of architecture forever. Here, philosophers would pontificate on the poetic qualities of a building, and architects themselves would return to the drawing board for their most radical designs. This was the dawn of visionary architecture.

To put it simply, visionary architecture is architecture that never makes it off the page; architecture that was never intended to make it off the page. Since the eighteenth century, visionary architects have popped up at key moments across history: “Piranesi pushed printmaking to incredible ends during the 18th century,” Clement Laurencio tells me, “[Étienne-Louis] Boullée with his Cenotaph and architecture parlante, [Vladimir] Tatlin and his Constructivist Tower for the Third International, Archigram and their projects in response to the sterility of modernism during the 60s: their works have defined their respective zeitgeists…through a drawing.”

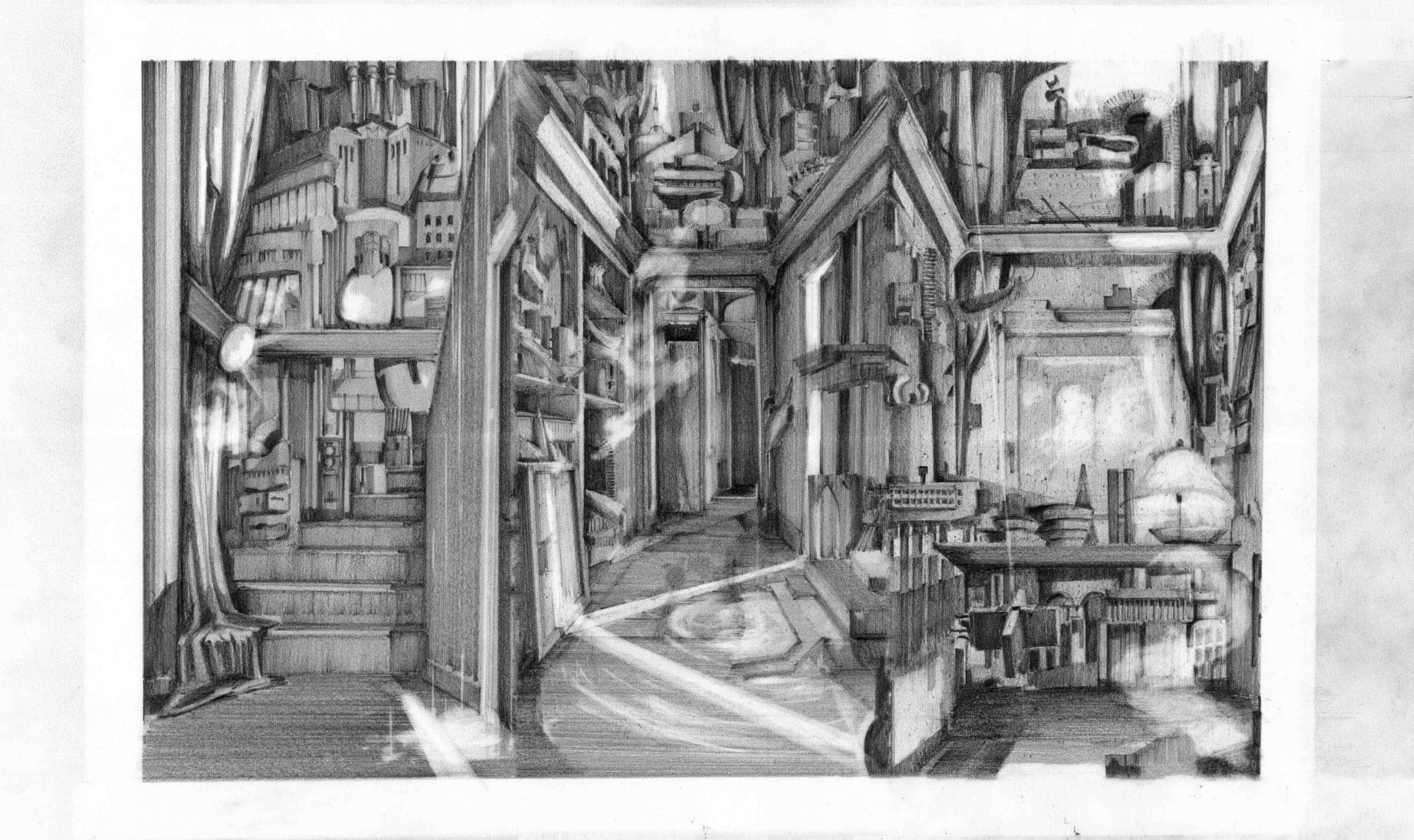

Memory Palace (2021)

Laurencio has just been awarded the Architecture Drawing Prize, established by World Architecture Festival, Sir John Soane’s Museum, and Make, back in 2018.

His labyrinthine architectural drawings fit firmly into the tradition of visionary architecture – though he’s reticent to accept such an accolade. We’re too close to ‘now’, he tells me, to know if we’re truly visionary or not: “Perhaps, only after many years’ time, with enough distance to look back at this moment, we will see that the projects which we imagined during this era of the pandemic were truly visionary.”

ArrayPavilions for Conversation (2019)

Originally from the Philippines, Clement Luk Laurencio was born in the south of France. After a childhood spent moving around the country (from the South, up to Paris, and over to the border of Geneva), Laurencio came to the UK to begin his architectural career at Nottingham University. He spent Part I of his architectural training working for the legendary Bernard Tschumi Architects in New York, before heading back to London to pursue his MArch at the Bartlett School of Architecture. And it was here that he began to develop what he calls his ‘spatial fictions’.

“I knew that my drawings were about the spaces around us, architecture, the built environment, so ‘spatial’ came first. But, I felt there was also this notion of fantasy, the way Antoniades thinks of the word: “that which exists in the clouds and in dreams”. So, ‘fiction’ came about. It also conveyed this notion of storytelling and narrative, which, I felt, was what gave life to the spaces I drew.”

It’s something that applies to all architecture, Laurencio tells me, because “at some point in time, the building exists only on paper (or in the cloud). Only until it is built, does it cease to become a spatial fiction, and becomes space.” I am reminded of something the poet John Ashbery once wrote: that “although all artists are visionaries in some sense, architects are perhaps the most radically visionary, since their aim is to alter the world and our lives.”

But if all architecture is visionary, visionary architecture must be through the roof (or in the clouds). So just what is it that these visions can do that the built environment can’t?

The Artist

“What Visionary Architecture can do,” Laurencio explains, “is to speculate on a potential architecture, an alternative world that is different from the reality in which we live in now. While it does teeter [on] the realm of pure fantasy, the rigour and precision of the architectural drawing slowly pulls it back to reality, which, for the briefest of moments, convinces one that it could potentially be built. It is precisely in this balance where we can indulge in our desires and let ourselves dream of the fiction that is in front of us.”

I ask Laurencio if he defines himself, first and foremost, as an architect or an artist, and he’s reluctant to pin himself to either: “perhaps something in between the two.” It’s the only thing a visionary architect can say (what would Piranesi have answered?), yet it raises the question of what makes visionary architecture architecture, and not simply visual art?

ArrayApartment #5, a Labyrinth and Repository of Spatial Memories (2020)

For Laurencio, in the spirit of Heidegger, it has something to do with dwelling, a concept that “means more than simply being within that space: it means absorbing the atmosphere of the place. To imagine grasping the warm door handle which has been basking in the afternoon sun, or hearing the echo of your footsteps on the stone pavement.”

To intensify these sensual qualities, Laurencio keeps his drawings unpopulated so that “the viewer [can] wander through the spaces on their own. Without the distractions from other people in the drawing, the viewer has the space to themselves, and are free to move and meander at their own pace. They can imagine climbing onto the roof, or standing under the cold rain in the Pavilion for Conversations drawings, or, pacing around the labyrinth of Apartment #5.”

It was Apartment #5 that earned Laurencio the Architecture Drawing Prize. Conceived and executed during last year’s lockdown, the piece captures the strangeness of physical stasis, of seeing the same four walls everyday, and the uncertainty of the future ahead, by drawing on memory – an idea Laurencio has picked up from the French poststructuralist thinker Gaston Bachelard. “We are isolated in our homes,” reads the text that accompanies Apartment #5, “left with our memories of those faraway places, with only our photographs to recall them.”

In this work, Laurencio fuses real and imagined space: the space of his apartment and photographs from a recent trip to India, merge with labyrinthine sketches that have been meticulously drawn by hand (usually at night, by lamplight – a fact that infuses these works with an air of visionary enigma).

Pavilions for Conversation (2019)

They have the quality of a half-remembered dream, a space we feel sure we’ve inhabited before, which its dizzying surreality assures us we never have. Looking at them, the question of what makes visionary architecture architecture, and not just a drawing, becomes redundant: the labyrinthine detail, the engineering precision, the ability to summon space is like nothing that painting alone can do.

Laurencio’s process is hybrid (part tactile, part digital), but the materially of the page and the hand of the artist are at the heart of everything he creates. “Back in my first year of architecture school, we were taught and encouraged to produce our design projects by hand-drawing them, and we spent many hours getting to grips with using Rotring technical pens. As Naja de Ostos says, drawing is our language, our lingua franca as architects and architecture students.”

ArraySoane’s Lost Room (2020)

For Laurencio, there’s something democratic in this. “The hand drawing really connects us all. At some point in everyone’s childhood, we picked up a pen or a pencil, and have doodled something. It is an act which we all are familiar with, wherever we come from.

Even since the dawn of mankind, we drew on the interior of caves, and our signatures today (which are in our own penmanship) are a part of our own identity: the marks we make are traces of ourselves.” Maybe this is where the possibility for dwelling inheres in the visionary – the trace of the artist’s hand, reaching out to pull the viewer in to the spaces projected from their minds.

The curator Hans Ulrich Obrist likes to conclude his interviews with artists and architects with a question about unfulfilled projects; yet as I ask this same question to Laurencio I realise that, by definition, all of his work is unfulfilled in some sense – its the nature of visionary architecture.

Does Laurencio have plans to draw a building that might get built from bricks and mortar? “Of course, it would be fulfilling to have one of my drawings built one day,” he says, “but for the moment, they exist and live on the surface of the paper. As long as the drawings inspire others to either to pick up a pencil, or to experience a moment of quiet contemplation – that is fulfilment enough for me.”