★★☆☆☆

Within the 90 minutes comprising this Peter Doherty documentary, made by his now-wife Katia deVidas, we see him smoke a fag while his body is cast in a crucifix position, perform on stage with his father making coke-snorting gestures, squirt lighter fluid around his living room then ignite it, reveal that he talks to furniture when he lacks sleep, get zonked on enough heroin to fell a woolly mammoth, and wince on a hospital bed while a drugs-blocking implant is inserted into his torso.

For better or worse, you do not get this sort of stuff from The 1975.

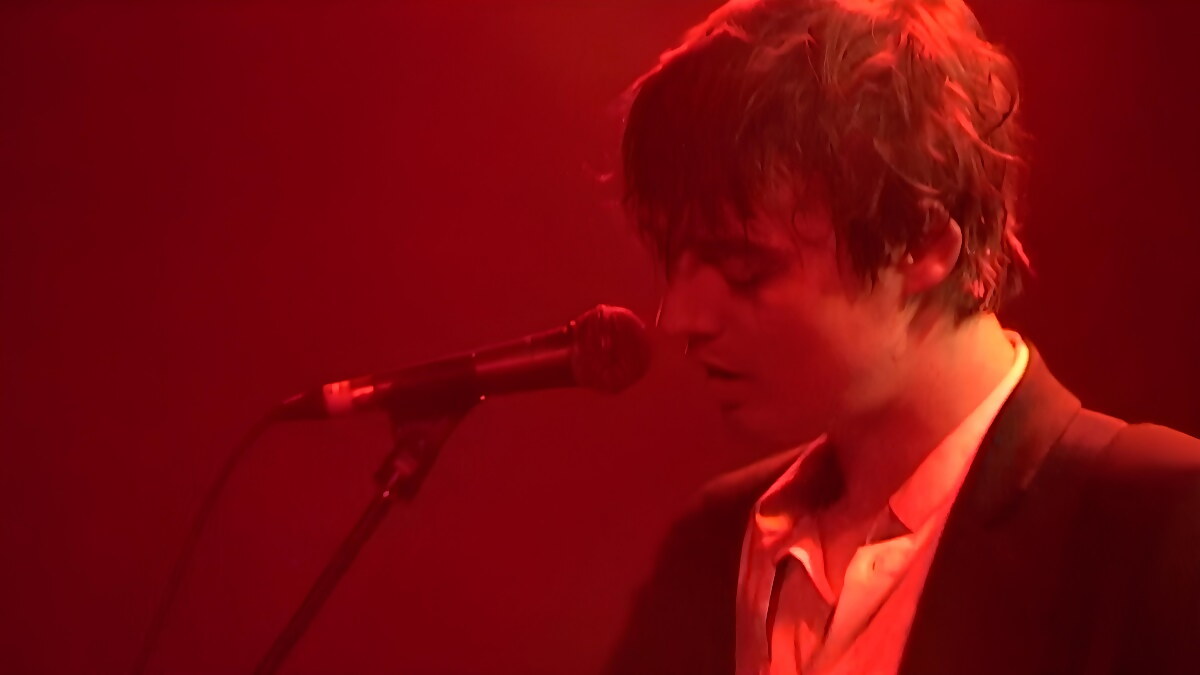

Doherty, as the main point of intrigue of his bands The Libertines and Babyshambles, was an agent of charismatic chaos as he found success, adoration and tabloid notoriety through the 2000s. deVidas was on hand through much of the 2010s to record his stumbly, mumbly attempts to make sense of his talent and demons, filming sweat-drenched live shows then the quiet comedowns: Doherty scribbling in diaries and taking drugs in the early hours, otherwise alone.

The result is a rickety ride-along with Britain’s last true decadent rock star that will please fans but offers little story or revelation.

After the whizz-bang success of The Libertines is quickly shown – on telly with Jonathan Ross, screeching fans, in NME every week – we see Doherty in a stupor, drooling on his guitar as his tour bus drives through the night. He explains it was on a flight to Japan, on which he suffered heroin withdrawal, that he realised he was a full-blown addict. He talks of a “need for chaos and frenzy” fuelling his drive to perform, but quickly, his need for smack becomes just as influential.

Doherty says he started taking drugs due to romantic literary notions inspired by the likes of Hunter S Thompson and Thomas Chatterton. Before this, he was a model student (seven A*s at GCSE and two As at A-Level). Drugs seem linked to his creativity but simultaneously threaten his musical career, with his Libertines co-frontman Carl Barât kicking him out of the group due to his heroin consumption.

Doherty descends into intense friendships with creative criminals such as Peter ‘Wolfman’ Wolfe, whom we see Doherty greeting outside Pentonville prison. Wolfe collaborated with Doherty on their 2004 UK top ten single ‘For Lovers’, but this isn’t explained, so to non-Doherty aficionados, he’s just a craggy-faced mate whose presence is confusing.

Relationships such as these might help explain the vulnerabilities that creep up on Doherty when the gigs are over, and the entourage dissipates, but they aren’t splayed open here. We see Doherty and Barât nudge heads and finish each other’s sentences as they announce a Libertines reunion, but their raging marriage-like attachment, that first set Doherty on the path to success, isn’t probed in the footage or Doherty’s narration (there are no talking heads in the film). We briefly hear Barat describing him and Doherty as “two one-legged men”, only becoming whole together.

READ MORE: ★★★★☆ The Libertines at Wembley Arena review | A nostalgic sense of occasion

Doherty talks of another estrangement from his father: a soldier who imposed militaristic limits on his teenage son. But how deeply this seeded a desire in Doherty to leap the barbed wire and create his own alternative literary world that ended up becoming bought into by swathes of fervently loyal fans is breezed over, as is father and son’s eventual reconciliation at a gig. Doherty says he’s “just grateful he’s not disowned me anymore”, but we’re not shown what caused the change or if it gave proper closure.

Doherty’s relationship with Kate Moss, which torpedoed him to the tabloid front pages as Britain’s number one rogue in brogues, is mentioned only in the context of him mentioning that inmates shouted, “You shagged Kate Moss!” when he was in prison for breaching probation. His friendship with Amy Winehouse, who became his lover as she became Britain’s top paparazzi target, is only shown in the context of an art piece the pair made together (that Doherty later flogged).

The depression spiral Winehouse’s death sent Doherty into isn’t addressed, nor is the death following the heroin overdose of his close musician friend Alan Wass, who is briefly seen in the footage. Mark Blanco, the actor who died in 2006 after falling from a balcony at a party Doherty was attending, that police questioned Doherty about (he has never been suspected or accused of wrongdoing in relation to this), isn’t mentioned. deVidas may have started filming after some of these events, but they cast shadows on Doherty that must have lingered.

deVidas, too, could have been more visible in the story she’s telling. She said she stopped filming Doherty when they became romantically involved, which is fair enough, but showing how he finally evolved into a family man could feel relevant and new. We get just a glimpse of their love – as deVidas films Doherty at a Thai rehab centre, she extends her hand from behind the camera, and we see the pair’s fingers intertwine.

30.09.21 ♥️ pic.twitter.com/XR1FGVWOCN

— Peter Doherty (@petedoherty) October 5, 2021

Doherty can be brazenly open on record and could have been probed for narration about how all these connections shaped him, although discussing supermodel exes might admittedly have been awkward.

Indeed, the project’s main flaw is that Doherty has already had so much of his life on full public show the unearthing of years worth of intimate footage doesn’t feel like a big reveal. He used to post videos on YouTube of himself in the bath. He complained about lawyers removing too many passages from his recent memoir, A Likely Lad. He’s smoked substances in drug paraphernalia-strewn apartments during interviews while slagging off Barât or talking about affairs with famous actresses. Forget Doherty’s soul being exposed; we already feel intimately familiar with the stained soles of his feet.

Still, despite many assuming he wouldn’t live to middle age, Doherty’s eventual escape from narcotic jail gives deVidas’ doc a happy ending. It won’t be a spoiler to anyone who has read about Doherty recently to learn that he gets clean and stabilises The Libertines, who are releasing a new album soon.

Fans of the man and band will enjoy mainlining this tar-dark all-access adventure ahead of this new music arriving, but Stranger in My Own Skin is footage rather than a film. As Doherty says, in one of many poetic narration lines: “Scraps of music, songs, poems, that which can’t be captured in a neatly arranged story, because there is no neat, arranged story.”

Stranger in My Own Skin arrives in cinemas on 9 November.

Want to write about music? Pitch us your ideas.

Are you passionate about music and have a story or hot take to share? whynow wants to hear from you. Send your music-focused pitch to editors@whynow.co.uk. Let’s make some noise together.