Video games have long been seen as impossible to adapt to the big (or small) screen. Many have tried, many have failed. Adaptations like Assassin’s Creed and Resident Evil have proved that it’s a tricky genre to master. HBO’s The Last of Us has been hailed as the best video game adaptation yet and Connor Norcott explains why.

It’s no small secret that there have been a plethora of video game adaptations for the big and small screens alike, and it’s even less of a secret that the majority of those are more a miss than they are a hit. Thankfully, with HBO’s new adaptation of The Last of Us, critics, fans, and newcomers alike are being treated to a homerun on all fronts. The series currently stands at 99% on Rotten Tomatoes.

That being said, video game adaptations are tricky and those that falter tend to fail at the first hurdle; understanding what separates the two mediums, and how to maximise the opportunities and sidestep the pitfalls that come with this process. In the majority of these adaptations, the biggest problem lies with the audience.

No, it’s not dealing with unrealistic expectations or wild fancastings, it’s much simpler than that. How do you translate the sense of agency and input players experience when they fire up their console, into hour-long episodes of television? Well, in the case of The Last of Us, you simply don’t. You do what you know, and you do it well.

Credit: HBO

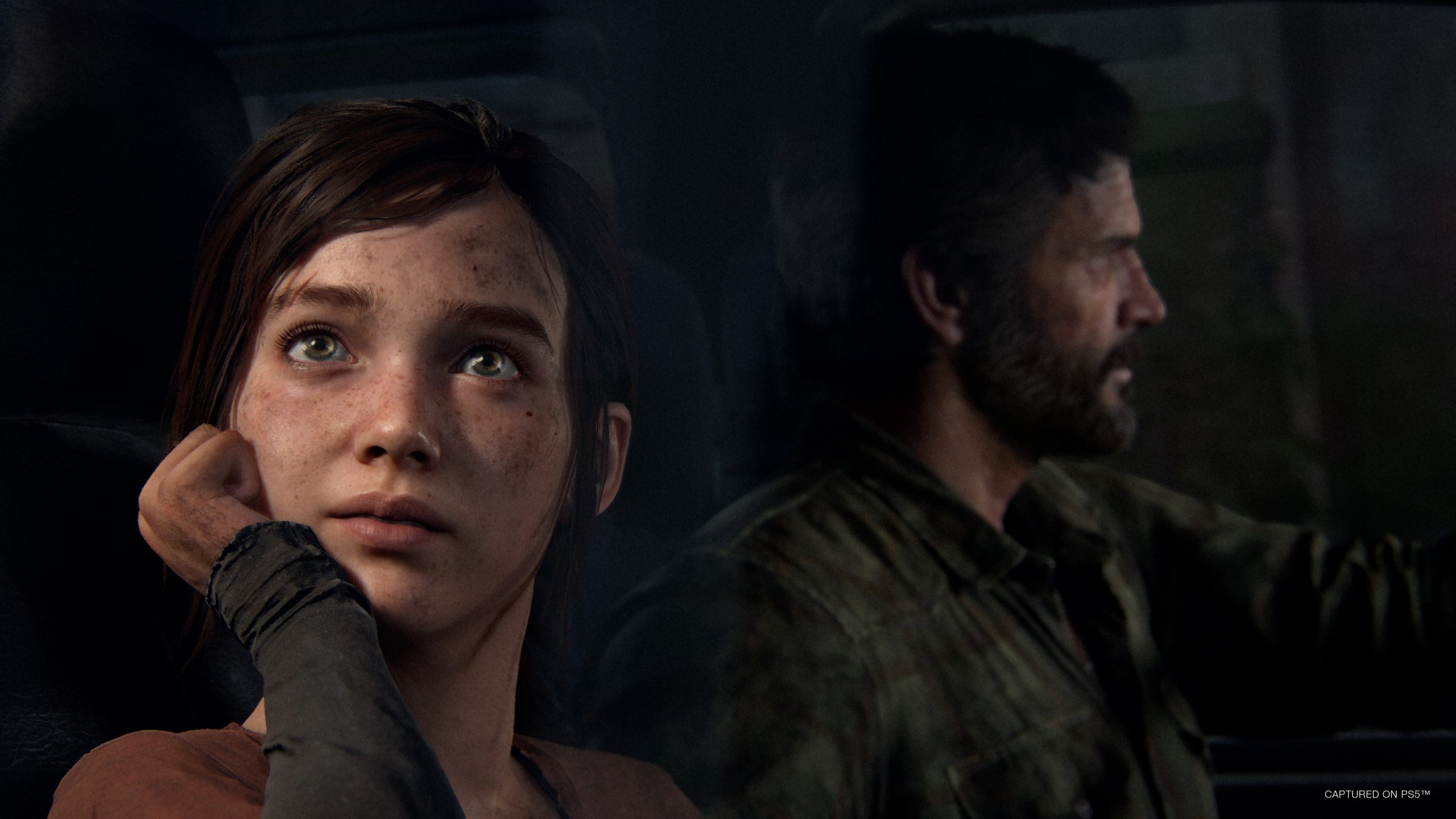

Adapted for television by the game’s writer/director/producer extraordinaire Neil Druckmann, along with acclaimed showrunner Craig Mazin (Chernobyl) The Last of Us sticks very closely to its beloved source material. In the game, set twenty years after a vicious cordyceps outbreak, you play as Joel Miller, a black-market smuggler, who is tasked with journeying across a post-apocalyptic America with the precocious Ellie, a wise-cracking and foul-mouthed teenage girl that just might be humanity’s last hope.

On the road, you’ll encounter a whole host of nasties (human and infected alike), scavenge for supplies, and fend off warring factions each with their own ulterior motives. If these beats form the skeletal structure of the game, and thus its television counterpart, the beating heart of The Last of Us is the relationship between Joel and Ellie, expertly brought to life by Troy Baker and Ashley Johnson in the game, and now re-imagined with Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey in the roles.

If you think you’re getting a like-for-like retelling, you’d be dead wrong. The showrunners have taken quite a few creative liberties in order to keep things fresh for returning fans.

Credit: HBO

Take for instance the show’s cold open, set in 1968, where two epidemiologists amicably debate the effects possible viruses could cause on humanity. Dr. Neuman (John Hannah) notes that even a slight shift in global temperature could see seemingly innocuous fungi like cordyceps mutate into something much more dangerous. What appears as typical TV-schtick at first, is actually a brilliant way to frame what follows.

Fans of the original will know the tragic outcome of Joel’s daughter Sarah in the prologue; and where the game takes no time to kick the pandemic into full swing (us gamers are an impatient bunch after all), the television show lingers on the Millers’ life pre-outbreak. As things start going south, the dread instilled from the cold open seeps into every subsequent scene, rendering the fallout that much more of a gut-punch.

Druckmann and Mazin, who was a dyed-in-the-wool fan of the franchise before coming on board as co-creator, understand where and when to deviate from the game’s locked-off perspective. In the game, players have no choice but to actively experience the world through Joel’s point of view: controlling him gives players the power to experience the story and its side characters at whatever pace, difficulty or even level of engagement they so choose. They are active participants in their own fate.

HBO’s The Last of Us brilliantly eschews this by playing with that idea of perspective. Whereas in the original, characters like Tess, Bill and Frank served to colour in Joel’s (and thus the player’s) experiences, its television equivalent dedicates more time and attention to those fan favourite characters. Their stories feel so real and so lived in, that any potential threat that may come their way feels tantamount to the importance of Joel and Ellie’s mission. For those faint of heart, be warned that peril is never too far away.

The Last of Us Part I remake was released in 2022. Credit: Naughty Dog

Post-apocalyptic stories are always interesting, and The Last of Us is no different. It has rightly drawn comparisons to Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road thanks to its desolate, overgrown landscapes and grisly violence. Mazin’s experience with the brutal and cold world of HBO’s Chernobyl definitely comes into play here, and he’s a perfect match for the genre. His understanding of what makes a particular scene or moment so bone-chilling adds weight and pressure to each dangerous encounter, and his command of tension and tone ensures that even the boldest of players-turner-viewers would be looking for the ‘skip cutscene’ option during certain moments.

Seriously, buckle up for episode three.

These slight variations go a long way to colouring in the lines for what fans of the game already know, as well as throwing up some surprises along the way to keep them on their toes. What’s remarkable is that despite the list of the changes, some of which are relatively large in reflection, each one feels considered, if not necessary for the show. Everything is streamlined to push the narrative forward, and despite some of the lengthy run-times, each episode has an ingrained sense of urgency and danger that promises to keep the show’s stakes high, and its viewers engaged.

The best adaptations don’t tread the same steps as their predecessors, they work as companion pieces, uplifting their source material and examining it through a different lens. If solving the lack of player agency is the main question when creating a video game adaptation, the answer is keeping audiences hooked with every scene; and with a finely tuned balance of loyalty to the source material, clever casting, nuanced changes, easter eggs and moments of edge-of-your-seat suspense, The Last of Us does this, and then some.