I have to confess that throughout The Painter and the Thief, one question preoccupied me: why on earth did the director decide to make the film look like a documentary? I watched the film ‘blind’, as it were, without prior research, partly to avoid reading anything that might prejudice my viewing, partly due to a hectic first week of the London Film Festival, where the film had its UK premiere.

After the film, watching the Q&A with the director, 31-year-old Benjamin Ree, I got my answer: it was a documentary.

ArrayWhy the confusion? For one thing, Ree, a self-declared film nerd, draws heavily on cinematic tropes so the film is redolent of fictional classics. Another reason is that the story is quite incredible – in both senses of the word.

It goes like this: Barbora Kysilkova is a Czech painter who has just moved to Oslo to be with her Norwegian boyfriend. Not long after arriving, her work shows at a gallery where one day, two men break in and steal two of her paintings. Usually, we’re told, thieves would cut a canvas out of its frame with a knife. But these men carefully unstapled the canvas to preserve the painting’s integrity, a process that would have taken a professional at least an hour.

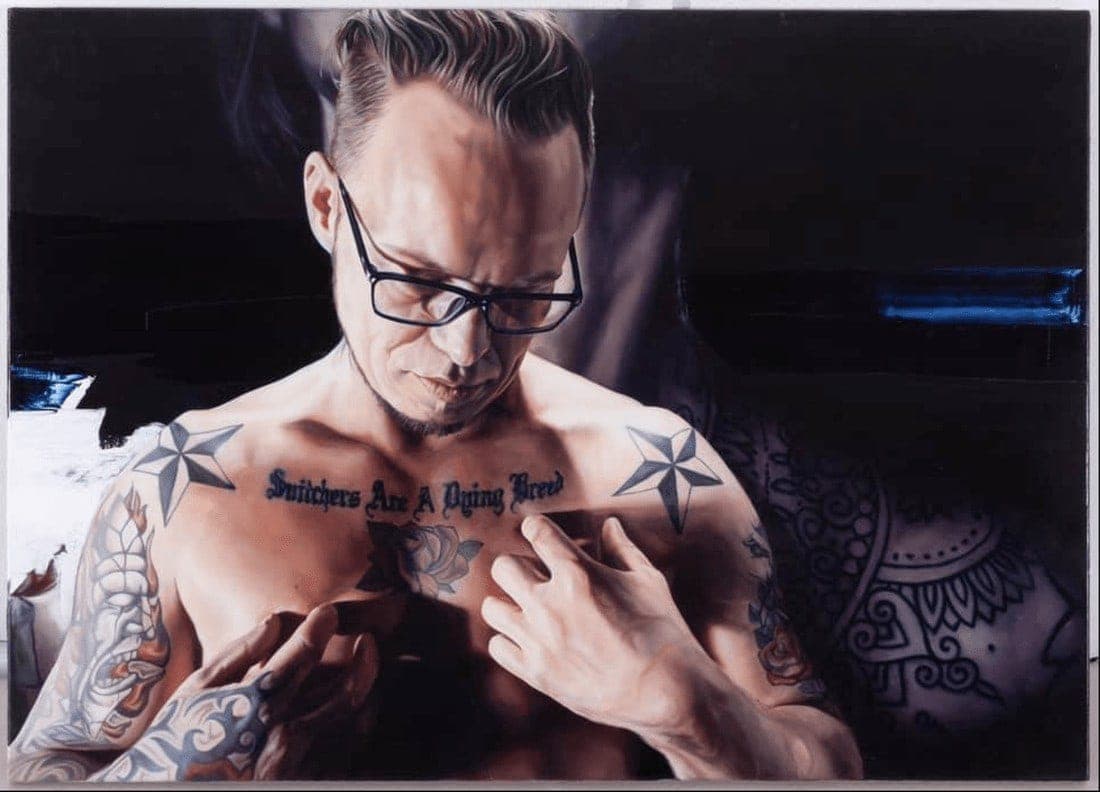

Police catch the thieves but they don’t find the paintings. Barbara attends the court proceedings and she is struck by the answer one of the men gives when asked why he took the painting. ‘Because it was beautiful,’ he says. Barbara approaches the man, Karl-Bertil Nordland, a heavily tattooed petty criminal, and asks if she can paint his portrait. ‘That’s possible,’ he says. From there, they get to know one another, the painter and the thief.

The film charts the ups and downs of their unlikely friendship. Those ups and downs are largely Bertil’s. In a couple of years, he badly injures himself stealing a car and ends up back in prison. He goes to rehab, comes out, and gets himself clean.

ArrayThe film’s showpiece scene sees Barbara reveal her first portrait to Karl-Bertil. He visits her and, at first, doesn’t see the picture hanging behind him on the wall. Then he turns and sees it, and he begins to tremble and sob. ‘What the fuck?’ he manages to say through the tears.

‘The questions I would like to explore here are: what do humans do in order to be seen and appreciated?’ says Ree in the Q&A. The implication is that while Karl-Bertil steals and Barbara paints, both are finding ways to impose form on the chaos of the world, and both are finding ways to heal from traumatic childhoods.

There follows much narration by Karl-Bertil on his childhood, accompanied by slideshows of grainy photographs of his youth. We learn that Bertil’s mother took his siblings and moved away, leaving Bertil to grow up alone with his father. From there, he fell in with a group of bad boys. Of 13, he tells us, only two are still alive today. The others fell to murder, suicide, or overdoses.

His story is harrowing but not always compelling. One result of the film’s fictional feature film style is that it’s tempting to judge it by the criteria one brings to a fiction feature, and by those criteria The Painter and the Thief is missing something. For one thing, many of the story’s most dramatic moments happen off-camera. What the audience gets to see is mostly the long and harmonious relationship between Bertil and Barbora. It is touching, but as another Karl-Bertil monologue begins, one worries the story’s energy is already spent.

ArraySome of the most compelling moments are the dialogues between Barbora and her gentle and empathetic Norwegian boyfriend, who probes the artist on the ethics of her interest in Bertil. Is it voyeuristic? Self-indulgent? Self-destructive?

Bertil sees this, too. ‘She sees me very well,’ he says, ‘but she forgets that I can see her, too.’

Near the film’s end, we see Barbora discover one of her missing paintings through Karl-Bertil’s accomplice. The camera follows the artist as she goes to recover it from the house of a dangerous Oslo gangster. Barbora is shocked to find her painting rolled up in the corner of a dusty loft. Yet we see here that recovering the paintings was never the story of this film. The real story is the relationship between two troubled people who in each other’s company, find unlikely ways to feel, see, and be seen.