Tate Britain’s The Rossettis provides a fresh look at the pre-Raphaelites and a unique insight into previously unheard working class experiences, creating a dream world heavy with psychological intrigue, writes Frances Forbes-Carbines.

Header Image: Dante Gabriel Rossetti , Venus Verticordia, 1868 © Private Collection

The year is 1865, and your glorious hair, long neck and graceful gait have caught the eye of an inquisitive artist: initially alarmed as he doggedly pursues you down the Strand, your unease lifts when he praises your beauty and tentatively asks you to sit for him one afternoon. Before long you are officially the artist’s model: a spacious studio setting and a weekly fee that earns you twice as much as your previous employment as a dressmaker in Victorian London. This artist knows people – other artists who have exhibited widely – and they want you to model for them, too. You, child of a family of piano-makers and butchers, are suddenly immortalised in works of art that hang in galleries. The public stands rapt before paintings in which you pose, hair loose around your shoulders, in sumptuous gowns made for you. The artists refer to you as a stunner. Don’t let it go to your head: your reversal of fortunes will be tempered by the agonising stabs of peritonitis you’ll endure while sitting for portrait sessions. Your life will be extinguished at the age of 37; the public that so feted you will barely know your name a century later.

The fate of artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s model Alexa Wilding was, if anything, no worse than that which befell other models of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), a group of English painters, poets and art critics founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais. The Rossettis at Tate Britain, a major retrospective of the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Rossetti née Siddal and featuring the poetry of Christina Rossetti, brings us a fresh look at the pre-Raphaelites and, with a section devoted to the models who sat for the artists, gives us unique and valuable insights into previously unheard working class experiences. The Rossettis exhibition is no candied assortment of knights and blessed damozels in citadels: instead we are shown the real, careworn faces of suffering rendered all the more poignant by their having been framed by the pageantry of Arthurian fantasy. There is a sadness and a stillness in their expression that betrays lives of financial precarity; lives where illness was never wholly absent.

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, Lady Affixing Pennant to a Knight’s Spear, 1856 © Tate

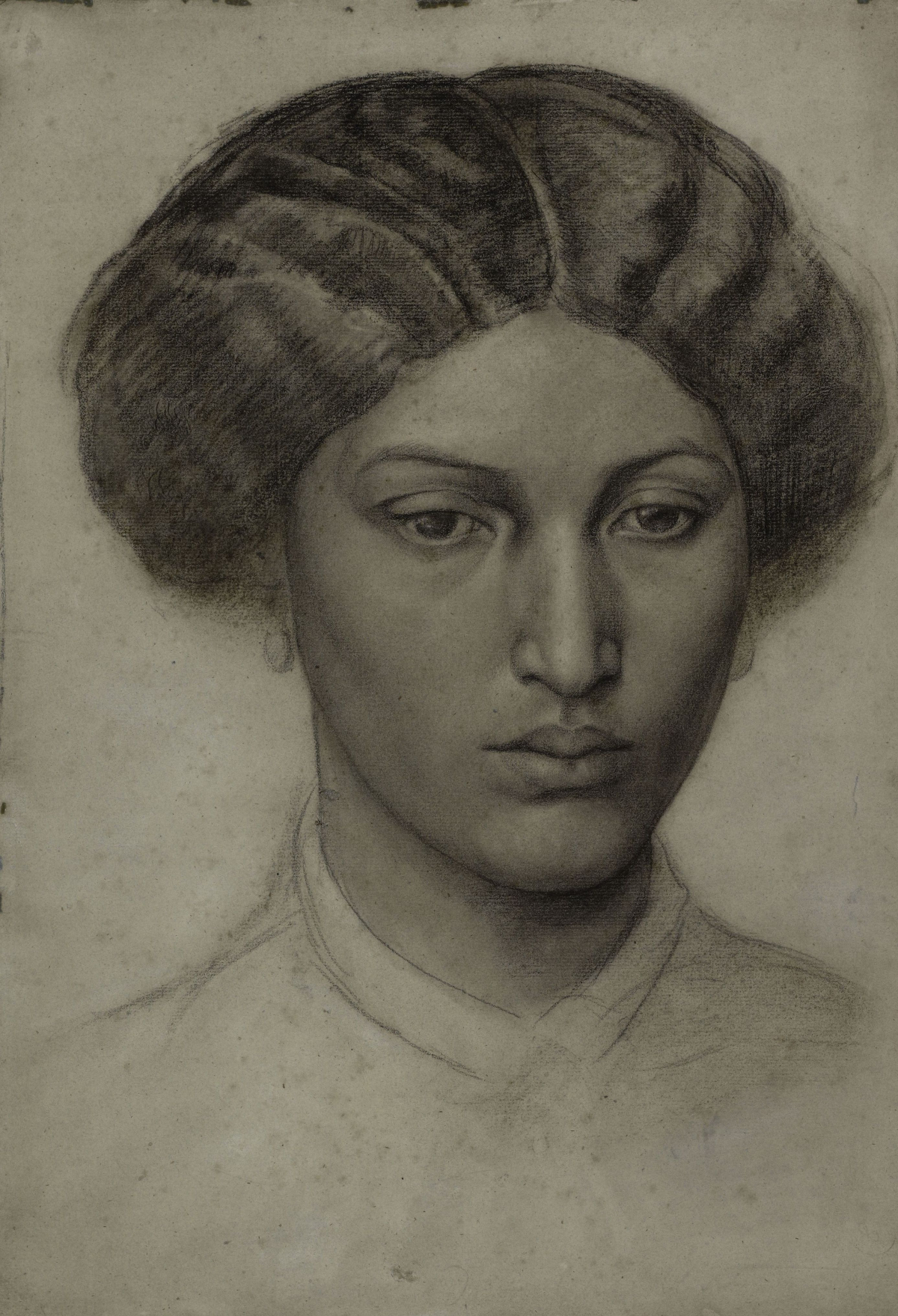

While the exhibition showcases works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882) as the first retrospective of the artist ever held at Tate, it also features a wealth of rare surviving works by Elizabeth Siddal (1829 – 1862). Exhibition curator Dr Carol Jacobi relates that Siddal was extraordinary for her time “not only as a woman artist, but as a working class artist”. The model for Millais’ revered painting Ophelia in which the titular Shakespearean character clasps flowers to her bosom, drowned and half-submerged, “Lizzie” Siddal would become the muse and model of Dante Gabriel Rossetti before becoming a painter herself, in what Carol Jacobi describes as a “short, interrupted career” beset by illness and an early death. As biographer, curator and specialist in the Pre-Raphaelite period Jan Marsh has emphasised, Siddal was not from an entirely destitute background as has previously been claimed in contemporaneous biographies: she was not raised in the slums of London, but brought up in a household of petit bourgeois aspirations typical of the impoverished gentry.

While Gabriel’s childhood left him enthralled to Florentine literature, across town Elizabeth grew up reading the poetry of Tennyson. Her works displayed in the exhibition show her dedication to her early education: art historian Ruth Millington writes in her book Muse: Uncovering The Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces that Siddal possessed a deep knowledge of art and literature, and that this aided her willingness “to impersonate characters [for the pre-Raphaelite artists] with understanding and dedication”. Despite this, we collectively remember Siddal as being a tragic muse, rather than creator: in 1862 at the age of 32, she took a fatal overdose of laudanum, an opiate she’d routinely taken for years by way of alleviating the discomfort of what was thought to be tuberculosis. The bereaved Gabriel would remember her through the creation of his painting Beata Beatrix, taking inspiration from Dante Alighieri’s La Vita Nuova, in which Alighieri mourns his love, Beatrix.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, 1864 © Tate

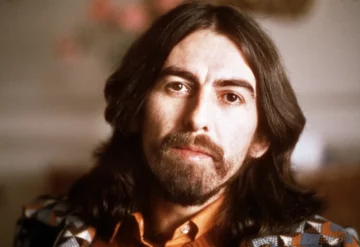

Curator Dr James Finch emphasised to me the importance of viewing the involvement of the Pre-Raphaelites’ models in the artistic process as the labour of creators, rather than that of mere muses. This is in accordance with conversations surrounding artists’ models in the twenty first century: I viewed The Rossettis from my standpoint of having worked as an artists’ model for the better part of a decade; navigating portrait and life classes and actively collaborating with artists towards creating compositions while bringing to the table my knowledge of art history. These developments with regards to how we think about artists’ models are closely linked to new biographical discoveries: as Finch noted, “it is a boon that owing to recent research, we are able to say more about the lives of the models and the impact of their work”.

The exhibition includes one of Gabriel’s finest portraits, on loan from Stanford University in California: a model named Fanny Eaton. Born in Jamaica in 1835 to an enslaved mother, Eaton moved to London in the 1840s and in her twenties was a celebrated artists’ model, hired by Millais and Joanna Mary Boyce and regarded by the Pre-Raphaelite brethren as a model of ideal beauty. In an age of colonial expansion, when artists tended only to employ people of colour as models within a narrow parameters of representing biblical and “oriental” roles, the intense subjectivity of Gabriel’s portrait of Mrs Eaton stands out as being unconventional, and speaks less of Gabriel’s technique than it does of Eaton’s incomparable skills as a collaborator in the artistic process.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti Head of a Young Woman [Mrs. Eaton] 1863-65 © Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University