To coincide with the National Gallery’s The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance, Emily Watkins reveals what Jennifer Coolidge and a 500-year-old painting have in common.

Sugar, spice and all things nice – that’s what little girls, and the women they grow into, are supposed to be made of. From the oldest depictions of women to the present day, Western visual culture has not only prized female beauty above all else but aligned it with moral virtue too. Imagine, if you can, how many times the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus has been painted; yet, for all her variety – Italian or Flemish, by Rubens or da Vinci – she is reliably young, beautiful, expressionless: the perfect woman.

Per psychoanalysis’s Madonna-whore complex, the patriarchy doesn’t consider female attractiveness a straightforwardly positive force – for every butter-wouldn’t-melt Mary, a seductive Magdalene is waiting to lure unwitting men from the path of righteousness. Beauty can be frightening as well as alluring, then – but even the knottiest feelings can’t obscure the fact that our paragons of moral good almost always align with our paragons of beauty, and vice versa.

To illustrate the point with recent visual history, look to Disney films: here, goodies are pretty and baddies are not (think of Ariel vs Ursula in The Little Mermaid, or Cinderella and her Ugly Sisters). This stuff starts so early and goes so deep that I’d be surprised if you don’t recognise what I’m describing – but if in doubt, just remember that, when it comes to women, young = beautiful, beautiful = good, and good = subservient. Bad = well, anything else.

Credit: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures

With our moral landscape so clearly legible in the faces of its characters, any step over the lines is immediately and starkly visible; what’s more, you don’t need to be a sea witch to fall outside the ideal – being over age 25 or more than 120 lbs will do. As such, it seems worth mentioning that – after decades of subsisting on the thin gruel of female archetypes – the women on screen today are suddenly just as likely to exist beyond those narrow confines as to meet them.

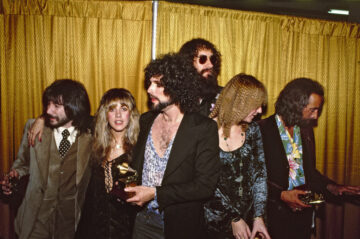

Olivia Colman in The Favourite, Cate Blanchett in Tár, Kate Winslet in Mare of Easttown, Jennifer Coolidge in The White Lotus; almost overnight, it seems we are being treated to a banquet of female characters who fit no archetype we’ve been trained to recognise, sending centuries of mopey princesses scattering in their wake.

Cate Blanchett as Lydia Tár. Credit: Universal Pictures

Three-dimensional arcs, nuanced motivations, rich inner lives – ambassador, you’re spoiling us! (In fact, actors like Blanchett and Winslet have timed this perfectly, ageing into much more interesting roles than they were permitted when they were younger and skipping the career cut off that has historically befallen actresses over 40: win-win).

So, what’s going on? Why are we suddenly permitting women to be people in public? Well, if the National Gallery’s show The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance is anything to go by, our appetite for difficult women with difficult faces might not be so new after all. Featuring the iconic painting An Old Woman (made circa 1513 and better known as ‘The Ugly Duchess’) by Flemish renaissance master Quinten Massys, the exhibition surveys historic attitudes to beauty, ageing, and the ways in which morality is conflated with attractiveness.

Quinten Massys’ An Old Woman, about 1514-24

Reunited with her accompanying portrait – An Old Man who she hopes to seduce, as the rose bud in her hand makes clear – the Duchess provides the show’s focal point as well as its title. While it has been suggested that Massys was painting a sitter with an ailment – specifically Paget’s disease, a rare condition which causes the bones to grow in abnormal ways – the consensus today is that the Duchess was not painted from life (a fact that an older cartoon of the same face by Francesco Melzi after Leonardo da Vinci, copied by Massys and displayed as part of the exhibition, makes plain).

As such, the artist could revel in – and exaggerate – her facial idiosyncrasies; the curious, crepe-y texture of the skin of her decolletage; the white hair in her facial mole; the delicate concertina of her jowls and neck. As curator Emma Capron explains, “the fact that he’s lavishing so much care and attention on something so indecorous – that tension between form and subject – is the joke.”

Quinten Massys’ An Old Man, about 1513

Working in the early 16th century in hyper-religious Europe, Massys would have relied on commissions from wealthy patrons, painting on demand to decorate their homes and altars. Countless Madonnas, hundreds of pietas, crucifixion after crucifixion – imagine what a novelty it would have been to have a whole new terrain to cover. “It goes back to a very famous quote by Umberto Eco, where he says, in many ways, beauty is boring because it always is confined by strict norms,” continues Capron “It has to answer to a certain understanding of harmony – whereas ugliness is free. It’s unpredictable and it’s infinite.”

Massys’ duchess might not be a paragon to aspire to, but she’s moralising in her own way. Used to convey a lesson about vanity – “inside [the painting] is also perhaps a critique aimed at the pretension there is in sitting for any portrait” – she is an object of mockery, pity, and of possibility too. Here is a woman, Massys seems to say, whose physical appearance diverges so acutely from the demands we have made of women that she is barely a woman at all.

It’s a message he expresses explicitly in the composition: sitting in context as part of her duo, the duchess is on the “proper right” – traditionally the preserve of the man in such tableaus. “She’s turning the world upside down, [by] taking the place of a man,” explains Capron. Yet, being ejected from her socially acceptable position presents opportunity as well as scandal, for the duchess herself and her artist alike. After all, if she’s not a wife or a mother or a bride or a beauty, then she could be anything: “ a very powerful move,” says Capron.

Quinten Massys, An Old Woman (‘The Ugly Duchess’), about 1513

Exiled – or liberated, depending who you ask – from the role that society assigned her, Massys’ duchess is an extreme example of a phenomenon we see played out every time we flick through Netflix today. Just as painting the faces of older women let artists experiment with techniques that they could never have exercised on their umpteenth Madonna, so actresses who step beyond the asphyxiating confines of Hollywood beauty standards find themselves penalised on the one hand, and whole realms of agency that their alluring daughters could only dream of on the other. It’s a step in the right direction, but more a battle won than a war.

Still permitted beauty or agency – never both – attitudes to women have arguably hardly changed since Massys painted his duchess more than 500 years ago. Viewed thus, the rash of ‘difficult’ female characters is less revolutionary than it might first seem; increased freedom for actresses to portray (and ergo, audiences to see) three-dimensional characters is surely a good thing – but a parallel expansion in the purview of leading ladies and love interests is yet to materialise.

“As a viewer, there is a kind of cathartic joy in beholding this woman trampling gender hierarchies, social conventions, canons of beauty;” speaking on The Ugly Duchess, Capron could be talking about any number of recent female characters on screen. “It’s complicated.” You’re telling me.

Jennifer Coolidge in The White Lotus. Credit: HBO

From renaissance Flanders to 2023 streaming culture, we remain trapped in the same old and-or dichotomy. Extracting female characters from the matrix of cinematic heterosexual desire — by making them ‘old’, ‘ugly’, queer, pick your poison — seems to grant them licence to do all sorts of interesting, complicated things. That is, obviously, great – but until we can hold both sex and subjectivity in our heads at once, we’re yet to cross the finish line.

Gleefully exploring the territory beyond those age-old beauty standards like it’s the promised land, we’ve forgotten our fight to expand the standards themselves. More productive, perhaps, to do away with them altogether – make like Massys and revel in every wrinkle. In Capron’s words, “He’s almost saying, well, you want something that reproduces the world around you, you want to get as close as possible to real life? I’ll give you that.” Careful what you wish for.