In this series, we’ll descend below the surface to explore the overlooked world beneath our streets: what’s down there and what these spaces have to tell us.

There’s a spot on Ray Street in Clerkenwell, just outside The Coach pub, where if you listen closely, you might detect the phantom rushing of a long-lost river. From its source in Hampstead Heath, it slopes southwards, passing under Kentish Town and flowing towards St Pancras Old Church before finally joining the Thames at Blackfriars. Except this is no phantom, this is London’s largest underground river: the Fleet.

Countless rivers, in fact, still flow underneath the capital, including the Tyburn, Walbrook, Westbourne, Peck and Effra. For most Londoners, these are largely forgotten, hidden as they are beneath layers of concrete, their sounds drowned out by traffic and construction noise, but these waterways bear a long and circuitous history that shaped the city as we know it today, influencing the urban landscape from building foundations to street names.

Samuel Scott’s, The Mouth of the River Fleet

Derived from the Anglo-Saxon flēot, meaning estuary or tidal inlet, the Fleet was once a vital artery of the city, providing not only a water source but also serving as a transport corridor into Northern London and generating power before the advent of fossil fuels. Yet like many of London’s other rivers, its flow reduced as the city’s population expanded, and the Fleet essentially became an open sewer. As early as 1290, the monks of Whitefriars complained to the King of the ‘putrid exhalations of the Fleet’, which overpowered the incense at mass. Centuries later, Jonathan Swift wrote of the river:

Sweepings from Butchers Stalls, Dung, Guts and Blood,

Drown’d puppies, stinking sprats, all drench’d in mud

Dead cats, and turnip-tops come tumbling down the flood.

These descriptions conjure an image of how the Fleet came to be and offer some idea as to why the river was eventually covered in the mid-19th century, buried and, for the most part, forgotten.

Despite being one of the world’s most heavily mapped countries – with the UK’s national mapping agency, Ordnance Survey, having charted almost every inch above ground – the underground remains mysteriously obscure. Beyond the underground rivers, there exist miles of new infrastructure that most of us on the surface have no idea about.

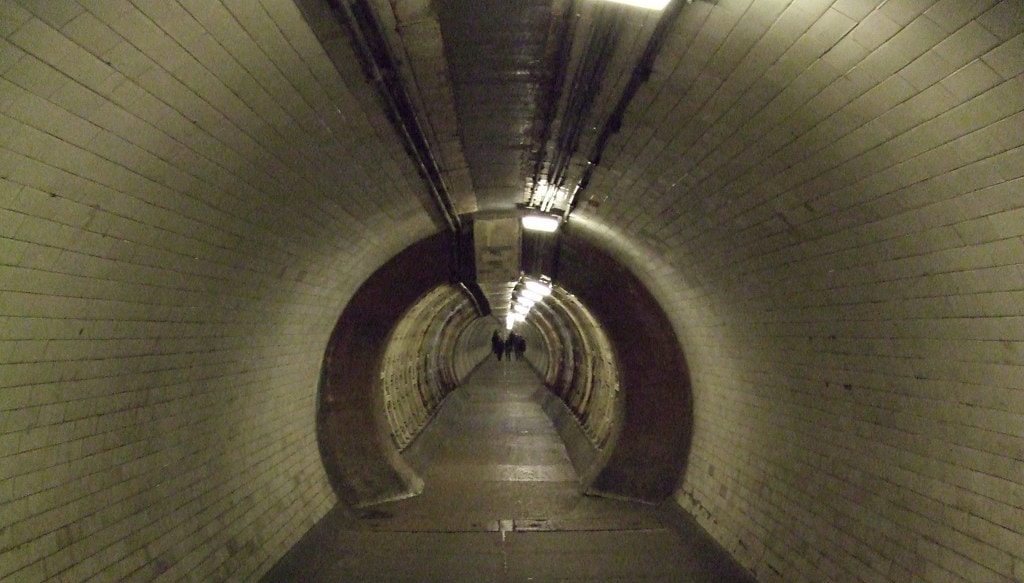

In his book Underground Cities: Mapping the tunnels, transits and networks underneath our feet (2020), Mark Ovenden writes that London “possesses one the world’s most diverse varieties of intricate, hidden and well-used passages, ducts and tubes beneath its streets”. This is, he said, partly because during the Industrial Revolution, there came a time when London became the busiest and most modern city in the world, which called for a need to utilise these vacant underground spaces.

30th July 1912: The Central London Railway extension platform at Liverpool Street Station.

Of course, one of the incredible feats of industrialisation was the London Underground, the oldest subterranean railway in the world, dating back to 1863. Today it sees around 1.8 million passengers a day, flitting between its 272 functioning stations. You might be one of them. And if you’re a regular passenger like I once was when I lived in London, you’ll probably have experienced something like this:

It’s late at night, and you’re travelling home on the Tube. Maybe you’re on your phone. Perhaps you’re staring unseeingly at the ads overhead. But suddenly, the train lurches and the lights start to flicker before the carriage is plunged into darkness. All you see are the thick cables glistening beyond murky windows. When the train stops, a platform appears, but it’s no ordinary platform, it’s covered in pigeon shit, and a sign announces DO NOT GET OUT. Along with sinkholes, this is my second underground phobia: arriving at one of these abandoned platforms and being stuck there forever.

As irrational as this fear might be, at least 40 of these abandoned stations are on the Tube network. While the reasons for their closure vary – from scarcity of passengers to lines being rerouted – these ghost stations are a natural byproduct of the city’s expansion. Many remain untouched and have inadvertently become time capsules of wartime Britain when the London Underground served as an overnight refuge for thousands of civilians during both World Wars.

Our #objectofthemonth is this cross section of Piccadilly Circus known as a stomach diagram as it shows the ‘insides’ of the station. Learn more about the history of Piccadilly Circus and explore its secret passageways on one of our #HiddenLondon tours. https://t.co/LBmWaEgXRE pic.twitter.com/0BAxgLupb2

— London Transport Museum (@ltmuseum) January 18, 2020

In the lead-up to WWII, authorities were resistant to using the underground as air raid shelters as they had done during the First World War, but the ferocity of the Blitz changed everything. On 7th September 1940, the first raid of the near-continuous bombing by German forces left 430 dead and 1,600 injured, almost the same number of casualties as sustained in all London raids in the First World War. Thousands flocked to the shelters, ushering in a rapid switch in policy.

Around this time, construction began on a series of deep-level shelters in London. These were designed to accommodate up to 8,000 people – each with their own assigned bunk and were to be situated beneath certain Underground stations. As the shelters weren’t completed until 1942, they were initially used by the government, but five were opened to the public in 1944 when the bombing intensified. (The deepest shelter at Clapham South also housed Jamaican immigrants from the MV Empire Windrush in 1948. Today, the shelter has been transformed into an underground farm).

One of Henry Moore’s Shelter Drawings from the Blitz. Image credit Sotheby’s.

Londoners tried their best to stay in high spirits underground despite the wartime conditions. As one shelterer, Theresa Griffin told TfL: “there used to be a lot of ‘Knees up Mother Brown’ going on… and drinking… and Christmas time there are carols and laughing and talking…by the time we’d finished we didn’t hear what was going on upstairs.” But the horror of the situation above-ground was far from forgotten. Over the next eight months, until the Blitz ended in May 1941, around 30,000 civilians were killed in London. Without the underground shelters, the number would likely be much higher.

These stations had other purposes, too, besides sheltering civilians during wartime. At the height of the Blitz, the Central Line was transformed into a secret aircraft components factory, where for four years, it served as a workplace for thousands of people – primarily women. Working long hours with poor ventilation, they assembled wiring sets for bombers, wireless equipment, field telephones, and Enigma Code-breaking’ Bombes’ for Bletchley Park. But it wasn’t until the 1980s that this factory was publicly revealed.

Records about underground spaces and their usage are so often veiled in secrecy. In 2017, Land Registry data exposed 4 million km of networks and telecommunications lines underneath London, many of which were constructed secretly by the Post Office, British Telecom, and the Ministry of Defence.

Browsing the dataset, British researcher, writer and campaigner Guy Shrubsole honed in on the point of interest: a ‘cable chamber’ owned by ‘His Majesty’s Postmaster General’ at the corner of Parliament Street and Bridge Street. “Why this small cable chamber is interesting,” he wrote for Who Owns England?, “is because it appears to corroborate other stories about Post Office tunnels beneath Whitehall, long the subject of legend on urban exploration online forums.”

In 1980, Duncan Campbell, a journalist investigating the government’s preparedness for nuclear war, came across an entrance to some of the Post Office tunnels and pedalled through them, ‘implausibly disguised as a touring cyclist. “A manhole cover, gently raised, gives access to one of the Post Office’s thousands of subsurface cable chambers,” he wrote. “But this one is different. Open it, and you are standing on the top platform of a shaft one hundred feet deep.” Tracing the tunnel towards Westminster, Campbell navigated “a Post Office lair called Q-Whitehall”, where shafts lead to various government offices above and patrolmen and ‘slavering Great Danes’ keep vigilance in the dark. The resulting article, a humorous critique of the Cold War security state, was published in the New Statesman’s Christmas edition, giving way to a rising curiosity about our undercity spaces.

George Jones’ Banquet in the Thames Tunnel

While there is currently no public access to any of these newly exposed tunnels, the Cabinet War Rooms – where Churchill sheltered during the Blitz and the later German V-weapon attacks – has been open to visitors since 1984. Thanks to this available data, it was only recently that a tunnel was identified running approximately 6km from Churchill’s underground headquarters to an access shaft on a traffic island in the middle of a public highway in Bethnal Green, E1. Who would’ve guessed?

The more you look, the more the underground expands and shifts beneath our feet, inviting us deeper into its mysterious labyrinthine realm. A world that feels so unknown and yet familiar at the same time. Despite the closely-guarded secrecy of these spaces, some groups and individuals remain committed to investigating the undercity to patch the missing data and extend our subterranean knowledge. And so, to the urban explorers helping bring these stories to light, we salute you.

In the next instalment of this series, we’ll look into the world of doomsday’ preppers’, exploring the phenomenon of nuclear bunkers across the globe.