In February 2023, an exhibition put on sale hundreds of works of art by Charles Bronson (AKA Charles Salvador). His controversial prison artwork raises questions about the relationship between infamy and artistic merit.

Header Image credit: The Charles Salvador Art Foundation

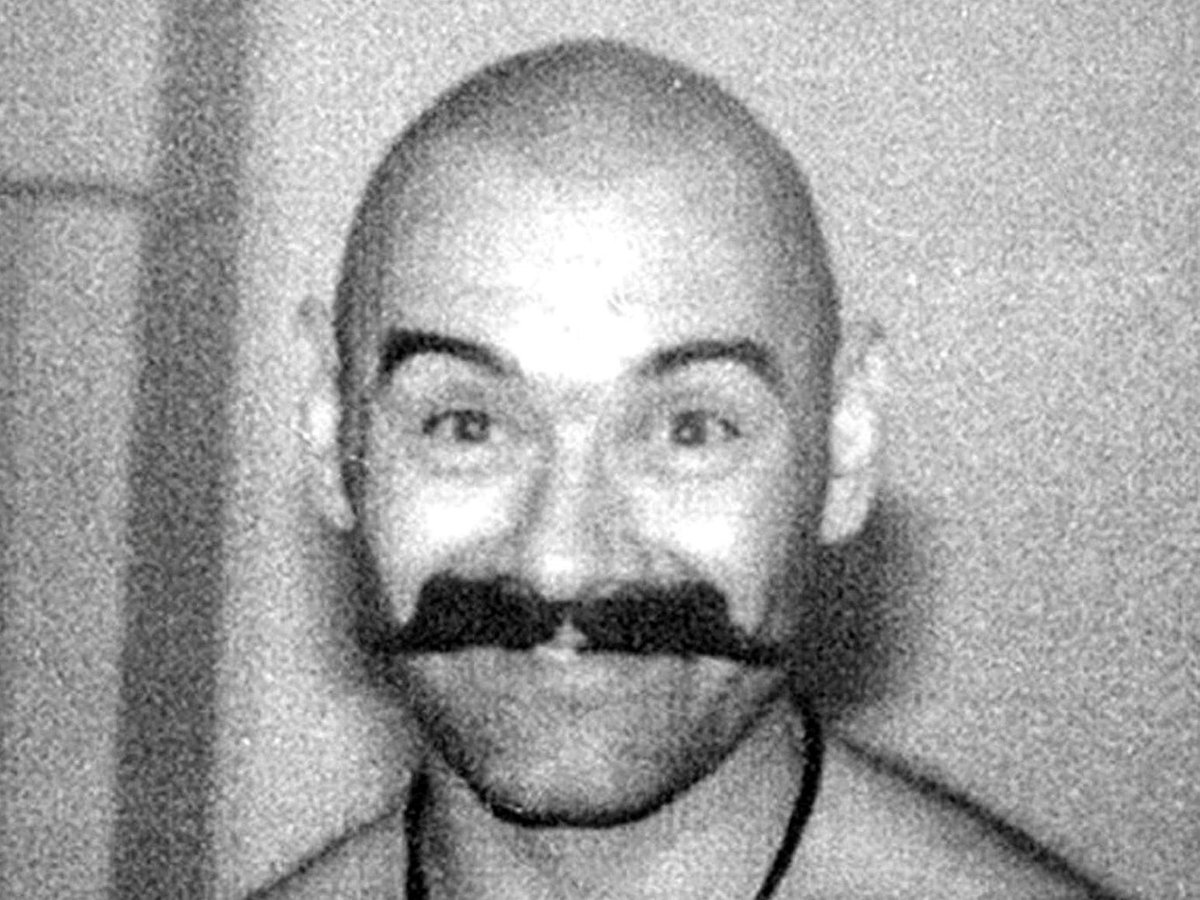

Charlie Bronson is the stuff of legend. Born Michael Peterson in 1952, he was initially jailed in 1974 for armed robbery. It wasn’t until he was in prison that he changed his name to Charles Bronson and drew out a seven-year sentence to extraordinary lengths. Extreme and repeated instances of violence, mainly against staff in the various institutions that housed him, resulted in 47 years and counting behind bars (27 in solitary confinement) and earnt Bronson the unofficial title of Britain’s most violent prisoner.

The man, the myth

His notoriety has been reflected in (and compounded by) pop culture – countless articles like this one have relished the gory details of his escapades. At the same time, Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2008 film Bronson, starring heart-throb Tom Hardy, offered viewers the chance to peer inside the head of the nation’s favourite bad guy. How does a person get to be that way? we ask, barely concealing our morbid fascination. And, uh, remind me how many hostages he took while he was inside? (FYI, the answer is nine, including a prison art teacher for three days in 1999).

Why do we love to pore over the minutiae of horrible crimes? Ask a sociologist, a criminologist, a true crime fan – but don’t ask Charlie because he’s turned over a new leaf! Now aged 70, Britain’s most infamous criminal is up for parole after nearly half a century in prison and a wholesale switch in focus from hostage-taking to careful shading. Since changing his name (again) to “Charles Salvador” – after his idol Salvador Dali – in 2014, Salvador (Bronson? Peterson?) has declared himself a “born-again artist”.

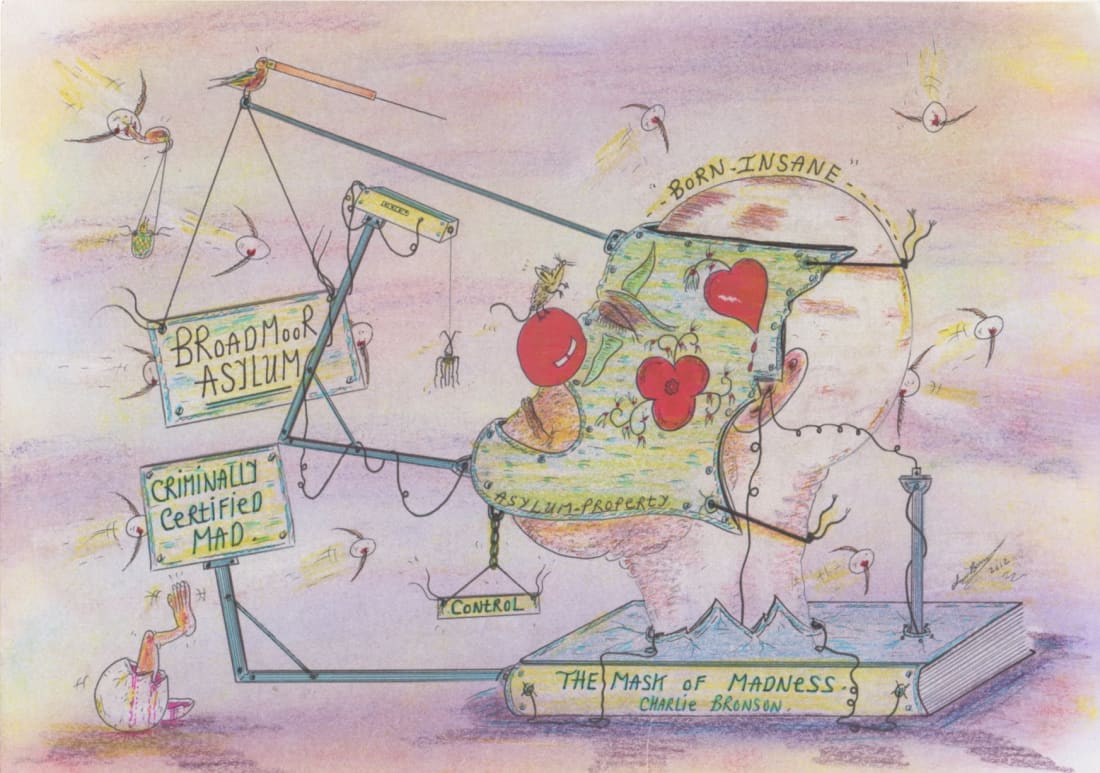

Art by Charles Bronson from 2009 | The Charles Salvador Art Foundation

Third name lucky

Making work in his cell and selling it through dealers in the outside world, Salvador’s current exhibition with Henarch Galleries in London coincided with his hearings this week – and, given the market’s appetite for his work, the show ought to stand him in good stead (naturally, an ex-prisoner’s ability to support themselves in the outside world is of paramount importance when considering parole). But here’s a question: would that same market give Bronson’s drawings a second glance if they were by someone less (in)famous?

Now, let the record show that I feel very strongly indeed about prisoners’ rights, as I do about the moral responsibility of a society to allow its outcasts a shot at re-integration; if 47 years isn’t enough time to keep someone in prison, then I’m not sure prison works. But this is not an article about prison – rather, about how an artist’s extraordinary biography, good or bad, distorts how we look at what they make. Think of readers staggering through interminable celebrity memoirs, not for the love of literature but for the parasocial thrill of being ‘near’ their favourite actor or singer.

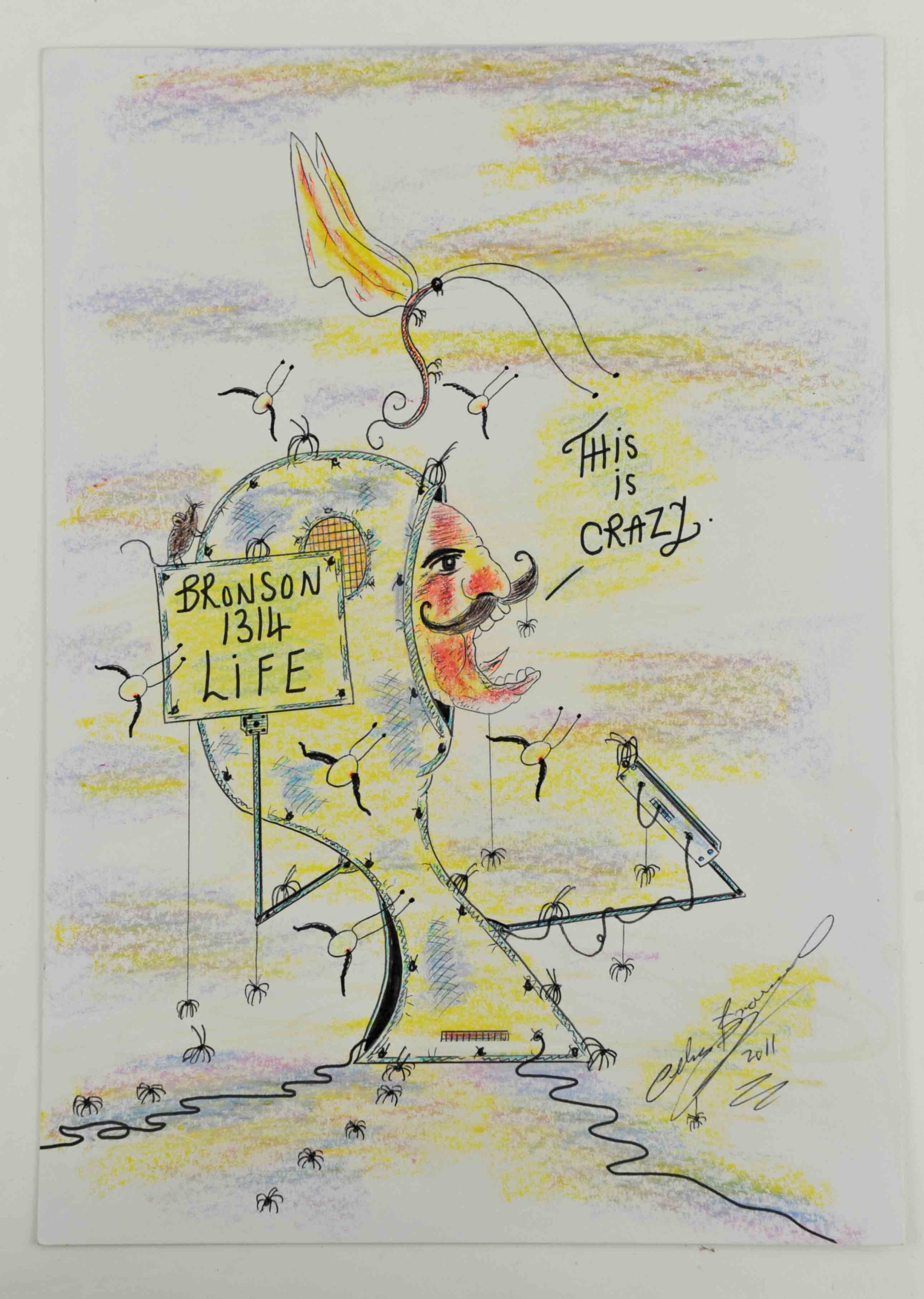

Charles Bronson art from 2011 | The Charles Salvador Art Foundation

Contagious! Outrageous!

Or consider bloated art giants, wrung dry of any interesting morsel they ever contained but with no negative impact on their market value – as long as the all-important signature or certificate accompanies the object. Even simple autographs from celebrities sell on secondary markets (eBay, auctions); there’s something of the saint’s relic about how we fetishise things touched by a human being we respect and admire. Interesting to note, then, that the same seems to apply when it comes to a person we theoretically feel less than warm about.

The contagion heuristic, in which an object is seen to hold – and potentially transmit – its prior owner’s ‘aura’, explains our collective madness. In the phenomenon’s classic example, called “Hitler’s Sweater”, subjects are asked to put on a jumper which they believe belonged to Adolf Hitler; perhaps unsurprisingly, they’re none too keen – and while the idea of transferrable ‘essence’ is inherently irrational, it goes deep. Thank God for that, because our superstition arguably keeps the art world turning.

Charles Bronson tells parole hearing “I am almost an angel now” as he urges them to free him from prison after almost half a century behind bars.@MinnieStephC4 reports.https://t.co/uIHPNwaIKP

— Channel 4 News (@Channel4News) March 6, 2023

Buying the biography

You can see Salvador’s drawings for yourself, at Henarch until March 23 or online here. Cartoon-y in spirit and style, they return (unsurprisingly) to themes of incarceration and mental illness: some are funny, and the best verge on Bosch-esque in their detail and sense of flippant chaos. From where I’m standing, the work’s not dreadful – but neither is it especially interesting, at least not on its own terms. No matter: those terms are the last thing we’re thinking about.

Just as buying a Damien Hirst tote feels like participating in a wider art ecosystem, acquiring a bit of YBA glamour and an inoffensive butterfly bag, a Bronson/Salvador represents much more than the paper it’s drawn on. There’s something caricatured about the man himself – his eccentric moustache, the bizarre details of his outsize crimes (taking a librarian hostage in 1994, then-Bronson demanded a doll, a cup of tea and helicopter as ransom) – that means he figures as an edgy folk hero rather than a villain in the popular imagination. The appeal of owning something by such a person feels clear on a gut level, if not an intellectual one. Quite apart from inverting or confounding the superstitious reasons that people want to own things, Salvador’s case exemplifies them.

You can follow the story of Charles Salvador’s (Bronson’s) life in prison and recent appeal for parole in the Channel 4 documentary “Bronson: Fit to Be Free?“.