A recent kerfuffle in the world of complaining about technology saw DJ David Guetta use a couple of A.I. websites to clone Eminem. Of course, not all of Eminem, just a few fresh bars that Eminem never spat. Guetta’s description of the process sounds like he created lyrics with current AI cause célèbre ChatGPT, then used a text-to-speech app to turn those lines into a rap. This home-style, deep-fake recording introduced a recent live set, captured on video and tweeted by Guetta himself.

Asked about the stunt at the BRIT Awards, the French producer told the BBC, “I’m sure the future of music is in A.I. For sure. There’s no doubt. But as a tool.”

Cue a slew of opinion editorials, most ignoring Guetta’s caveat: A.I. is here to stay but as a tool. They included a heartfelt and predictably poetic plea from murder-balladeer Nick Cave, appalled that a fan had used ChatGPT to generate a set of bloodless lyrics in his typical manner.

obviously I won’t release this commercially😃

— David Guetta (@davidguetta) February 4, 2023

Whenever there’s a sufficient technological leap, the critical headlines say the sky is falling. First, we clone Eminem. What next? Elvis duets with Michael Ball? New albums from artificial pop stars who have never taken a breath in the real world? Artists dragged from the dead to carry out further work?

Frankly, these things are already happening and are not all bad. New technologies aren’t intrinsically good or evil. It’s what we do with them. Let’s start with an observation that several of the naysayers have overlooked. A.I. isn’t just one thing. Even in Guetta’s simple example, there were two processes: the generation of lyrics and the creation of a vocal sample. A.I. is used throughout the industry to tune voices, generate harmonies and clean analogue data daily. A.I. is mainstream and right under our noses.

Artificial life support

Without A.I., there would have been no ABBA Voyage – the acclaimed, computer-generated live return of the Swedish pop legends that cost £140 million to produce. Deep fake technology was used to create digital “ABBAtars” of the veteran band in the sell-out show, allowing it to appear as if they were there in person in their prime.

And without A.I., there would have been no Get Back, Peter Jackson’s massively successful documentary using footage shot for the making of The Beatles’ Let It Be. Tools developed for Jackson’s 2018 WWI documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old upscaled existing pictures. New A.I.-powered software was used to separate and clean up the audio for remixing. Giles Martin then used the same tech to revisit and remix The Beatles’ Revolver for a new box set released in October 2022.

In both these examples, A.I. was used in collaboration with existing performances and newly generated content to enhance or recreate material. But there are also tasteful applications of A.I. tech to create classic performances that are entirely new.

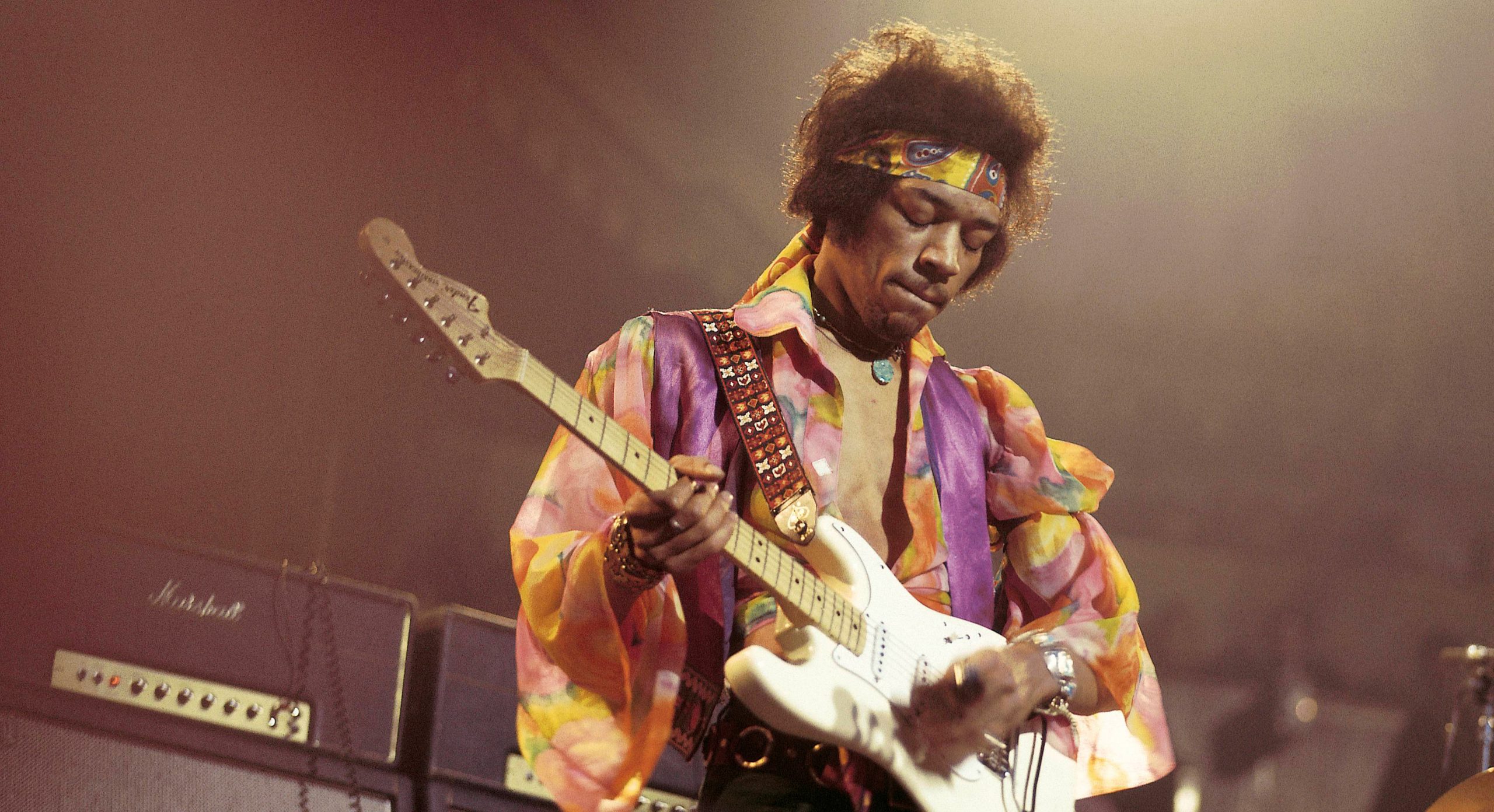

The Lost Tapes of the 27 Club project used A.I. to create new songs that mimicked the work of legendary artists who were gone too soon. Google Magenta tools analysed the musical styles, lyrics, and themes of Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain and others; an unspecified “neural network generated lyrics”.

The A.I. churned out MIDI files that were then used as a template for tribute acts to record songs that sounded remarkably like the original musicians. This potentially cheesy exercise was for a good cause, being developed by Over the Bridge – a non-profit mental health charity focusing on the music industry. The A.I. Doors and Hendrix tributes are particularly close to their human inspiration.

The experimental frontier

While these novelties are entertaining, amusing even, particularly given the growing value of legacy acts in the post-analogue industry, new technologies are most interesting at the fringes. One of the names that come up, again and again, is musician and researcher Benoit Carré.

The Lost Tapes of the 27 Club project used A.I. to create new songs that mimicked the work of legendary artists like Jimi Hendrix.

Working with Sony as Artistic Director for the A.I. project Flow Machines, Carré has steered several artists through music production using the company’s software tools, creating a handful of works under the name SKYGGE. The latest collection, Melancholia, is a challenging listen. With elements of modern classical, techno and glitch, the work sounds distinctly computer-generated. Of course, the same can often be said of other works in this area. Still, we also wonder how many “fans” Stockhausen had until his influence permeated the mainstream.

Edging closer to commercial acceptance – but only slightly – is Holly Herndon. A composer, musician, and academic, Herdon combines traditional songwriting techniques with artificial intelligence and machine-learning algorithms. Her 2019 album Proto featured a blend of human and glitchy machine voices. The album was made using a custom-built A.I. called “Spawn”, developed in collaboration with other musicians and computer scientists.

Though Proto was another difficult listen, Herndon followed this up in 2022 with a more conventional-sounding cover of Dolly Parton’s ‘Jolene’ – a duet with a digital twin of herself named Holly+. She followed this by releasing “Holly+” free online, so anyone can now upload their own audio tracks and have them “sung” by Holly’s A.I. doppelganger.

We’re already at an evolutionary stage of A.I. where software tools can generate polyphonic, instrumental music on demand in a genre of the user’s choosing – but many are shut away behind corporate doors. An exception is AIVA, a browser-based composition tool developed by Amper Music, which uses deep learning algorithms to analyse music data and create original compositions that emulate specific musical styles. In 2019, for instance, AIVA was used to compose the score for the short film I Am Human, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival.

From chaos to creation

Most collaborations between A.I. and musicians currently have a computer researcher working with artists, as was the case with 2022’s Everything Everything album Raw Data Feel. The album blends human and machine music generated with a custom-made system developed by programmer Afroditi Psarra. But as technology evolves, it becomes more accessible.

Every producer has their own favourite app to make music, but they all have one thing in common: they support AI plugins. Though most current AI-powered plugins add effects like echo or remove background noise, the number dedicated to generating grooves and tunes is growing. They might best be described as AI composition tools.

They have names like “Melodya” and “Scaler”, but most do similar things. They add features that make it easier and faster to create music. Some apps suggest chord progressions and melodies. Some plugins listen to what a producer is playing, then automatically jam along with them, adding bass or drums. Some programs can change a song’s key or tempo as easily and naturally as a real band.

A pattern emerges among all these; these apps don’t replace creativity – they enhance it. They suggest bass lines, melodies, and beats in styles and genres of the producer’s choosing. Every note in a song is now editable, and every sound can be swapped for another instrument. Welcome to the future.

When the BBC’s Mark Savage collared David Guetta on the BRITs red carpet, we think he said a mouthful. The creation of music is no longer just composition; it’s production. Even people who are not musicians know that recording has been digital for decades. Most of what we hear in the charts is a noise made by computers or chopped up and played back by computers. Guetta gets this.

In September 1962, when The Beatles recorded ‘Love Me Do’, the newly appointed Ringo Starr was an unknown quantity, so George Martin hired a session drummer. In 2023, he could have done the same or trusted the digital tools at his disposal to get a good performance out of Ringo. The drum track could have been quantised, humanised, pattern matched, chopped, changed and rearranged; the best bits looped for consistency. Or Martin could have disposed with real drummers, using a plugin to emulate a performance, particular style or another musician.

Creating recorded music has always been a process. Still, as time passes and technology improves, producers will have more choices at every stage. A.I. is about to revolutionise that process again.