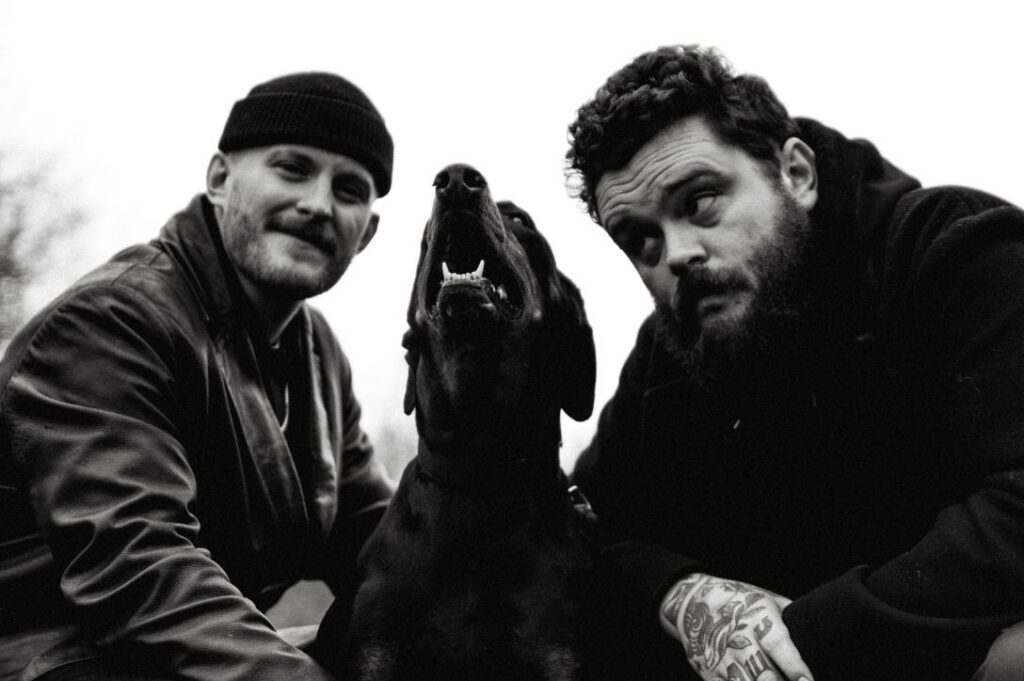

The monolithic legacy of industrialism still looms large over the Black Country – a region which owes its name to the Industrial Revolution – even in the generations since its demise. Birmingham’s Big Special are testament to that notion, and they couldn’t have said it more plainly than the title on the title of their debut album, Postindustrial Hometown Blues.

Disenchantment permeates the post-punk duo’s lyricism. Vocalist Joe Hicklin delivers his words with a wheezing exasperation that instantly evokes the plumes of smoke billowing out of the factories and coal mines of yesteryear. Cal Moloney’s enraged drumming personifies the frustration and resentment of growing up working-class with no pride or purpose in the remaining work in these left-behind communities. The pursuit of a music career often felt remote and unachievable.

But after years of juggling day jobs with their burden of creativity, the pair formed Big Special and embraced their regional, working-class experience as a superpower.

Ahead of the release of their debut album on So Records, we talked to Joe Hicklin and Cal Moloney about their voices being heard, reframing the generational shame of their Black Country beginnings, and how being a working-class musician is a political statement in itself:

Did you intend to make a political statement with Postindustrial Hometown Blues?

Joe: “It was never a ‘sit down and discuss what to do’ situation. It’s just our music, an honest reflection of our lives. We’re working class, from the West Midlands—the Black Country. If you’re just being honest about your life and the lives of those around you, it’s inherently political. Working-class bands and people who come from backgrounds that have no knowledge of how the music industry works feel like getting through to a certain point is political in and of itself.

“If you’re from our social background, your path is usually beaten out for you. There are few options for getting a job – labouring, working in shops etc. The powers that be don’t want you to progress and make art that slags them off. They don’t even want you to start up your own gardening business, you know, let alone publicly slight them. We’re just trying to be honest and creative, to make sh*t that’s true to us, to the best of our ability.

Cal: “Since I met Joe back in the day, his music has always had that classic blues narrative, the working man’s tunes. That’s where the political agenda is. You’re singing about the honest reflection of your life. Which is work. Which is what the majority of people in our country deal with. It’s political, but wasn’t premeditated. It’s just the nature of our music.”

There’s a line in ‘This Here Ain’t Water’ that’s stuck with me: “Standing on a history of factory fodder.” Do you think the Black Country’s identity as a former industrial powerhouse is an inescapable spectre?

Joe: “It looms over each generation. It was a place built on that. Generations of people were skilled labourers working in factories or mines. It was taken away at a certain point, even before our time. Lots of places in the country suffered a similar fate when everything was built on this industry before the f**king work was given away to cheaper places. There’s a taught shame about being working-class in that world. You’re not supposed to question. You’re supposed to struggle and crack on. Deal with what’s sent your way. There’s the history of going to work, and that is your life.

“When that work was taken away, the cultural identity was taken away, too. All these post-industrial towns are becoming ghost towns, money-making opportunities for local councils to turn everything into car parks. It’s just become a place where loads of f**king people reside and just live with discontentment forever—making just enough to get by, not asking for anything more. The album is trying to find poetry in the average life. The average life is really based on discontentment in this country. Putting up and shutting up. Not that we want too much anyway. We just want some identity and we want what’s ours.”

Would you have found it difficult to find purpose growing up if it weren’t for music?

Joe: “100%. That’s why we’ve been doing music for sixteen years, to no avail until recently. It was better to go without and to pursue music rather than just get by doing one of these jobs, and just continue doing that. That’s everything we’ve ever seen around here. People dream, but then ‘you’re done dreaming now’ and you’ve got to go to work. That is life, for sure. But there’s less room to dream about it round here.”

Cal: “Obviously it’s impossible to make money from music, so we’ve had a billion different jobs. But music’s never been a proper job, and it’s never been a proper hobby. The need to create is almost a burden as it prevents you finding enjoyment in any job really. Even a job in music – I got into session drumming before Big Special started, playing weddings, functions, sh*t like that. Trying to rationalise that I’m using my skill set, playing drums. But I’m playing f**king Marvin Gaye at weddings, when I want to express myself. I’ve got no beef with Marvin by the way.”

When did your paths first cross, and when did Big Special come into being?

Cal: “We met when we were seventeen, eighteen at a B-Tech college in Birmingham. From the off, we got on like a house on fire. We’d both been in bands and done bits before but hadn’t properly written music with anyone before. But we just clicked as mates and creatives. We found the same energy. We were in a few bands but eventually whittled it down to a two-piece, even then. I moved away, pursued the whole university thing and still did music to varying degrees of success. But it was during the pandemic when Joe messaged me saying he wanted to start a band.

“We’d stayed friends but hadn’t worked together for a long time. I was playing in function bands then and driving a van, so had money coming in with a full-time job. I was in my late twenties then, thinking if I don’t have it in me, so said no initially. He called me again a few weeks later though, and sent me the demo to ‘This Here Ain’t Water’ and that was the turning point. Listening to it I had the biggest grin on thinking ‘that’s exactly what I need to be doing’. Best second phone call I ever took.”

Joe: “Me and Mike, our producer, were just chatting about the demos and I just had a vision of Cal being there. It was Minnie, my wife, that convinced me to call him again. I was pacing up and down, and she said ‘just f**king ask him, he’ll get it’. He did, and that was it.”

Would there have been a third, fourth, or fifth phone call?

Cal: “There would’ve been a restraining order eventually.”

Joe: “I’ve mainly been a solo act. I’ve played in numerous bands but have always struggled to find a level of comfort playing with other people, even just with the people management. That was never a thing with Cal. But I’m glad for the ten years of experience we’ve had in-between. This is the most ‘us’ kind of art we’ve made.”

Did you know what you wanted Big Special to sound like?

Joe: “I mainly wanted to do spoken word, and not have to play live. Just be a vocalist and deliver my poems. Though I didn’t just want it to be with backing music. So I took my poems and used what I’ve learned to mould them into songs. I wanted it to be a cathartic thing, and say more. Without restriction of what I could say. With Cal next to be banging away on the drums. The rest was just experimentation really. We’d given up playing guitar on stage, which would reduce what we could make. We can make whatever the f*ck we want now in the context of knowing it’ll be a backing track. The middle ground between being a punk band and an electronic act. That was the main focus. Then we just messed around and made sh*t we liked the sound of.”

Your lyricism and spoken word delivery are both deeply poetic and evocative. Do you have any particular literary influences?

Joe: “It’s mainly lyricists. But I love books, poetry, and movies. Growing up, I was always impressed with someone saying something in their own way. You subconsciously connect to things, but you don’t choose them. I’ve always loved Charles Bukowski, Kerouac, John Cooper Clarke. Recently I’ve tried to connect with more local stuff. As we said earlier, because our cultural identity is lacking, at least on the surface, I’ve always connected with American culture. That was always the dream. Blues music, films in New York, Kerouac’s adventures. That was the stuff I loved. Getting older, it was about applying that to what was around me. With Big Special, it was a decision to reflect on this area.

“There’s a poet called Liz Berry from the Black Country. Discovering her encouraged me to brush off all my insecurities about my accent. I wasn’t thinking that separating myself from this area would make me an artist, it’s about digging into it and pulling it out. Everyone from the West Midlands is taught in some way to hate their accent, maybe because you don’t see it represented. For years I was scared to let my accent come through in my music, especially being poetic. I thought it’d sound stupid, but I was wrong. Finding Liz Berry’s poetry written in our dialect, seeing how unique and historically lyrical our accent is, it made me realise I have a thing here which is mine. It’s my tool.”

Recently, there’s been plenty of focus on the cost of touring and how increasingly difficult the realities of being a musician are for people from working-class backgrounds. How do you balance pursuing music with realities like paying bills?

Cal: “This is the first time we can say we’re actual musicians, after being signed. We’re proper full-timers. Touring’s got to a point where we can make a minimum wage off of merch, the label has helped with a publishing deal. The realities of being a working-class musicians if you ain’t signed is f**king hard graft. We did it for years. How much is the fee to the gig? Doesn’t cover the costs. Can’t get time off work, so you’re f**ked. I was in a lucky position being a self-employed van driver, so I was my own boss and could prioritise the band. The amount of bar jobs I’ve had where I couldn’t get the time off to tour, so quit. The instability you insert into your own life wanting to be a touring musician and to make rent is mad.”

Joe: “I’ve played music consistently for sixteen years, but last year was my first ever tour. It’s getting signed. I have all the respect in the world for independent artists that make stuff happen. But I don’t know how they do it.”

READ MORE: Sleaford Mods: ‘The working-class experience is too brutal for people. They don’t want to hear it’

Talking about touring, you recently supported Placebo in South America. What was that experience like?

Cal: “The maddest thing, to peep behind the curtain of what major touring was. I’ve never been south of the equator. We toured with Sleaford Mods last year, experiencing the ‘serious’ circuit, thinking ‘this is the biggest thing ever’. But to see the arenas out there, we were like ‘now this is the biggest thing ever’. I thought because our music was so Midlands, we were going to be a Midlands band, with people in London not even understanding us. The most gratifying thing of all though, was South America understanding us. Being proven wrong on such a grand scale. Going to South American audiences, hearing them chanting with us, understanding us.”

You said the album offers no answers, but do you think the message of POSTINDUSTRIAL HOMETOWN BLUES is to ensure the working-class experience isn’t erased from contemporary music?

Joe: It’s not our mission or the album’s. It’s just expression. Obviously, I’d love to see more working-class artists. The class conversation is still one that’s not discussed. There’s still shame around it. But there’s no mission statement on the album. It’s just going, ‘This is sh*t for all of us, and we’re in the sh*t together’. We’re always on the same side, but we’re always arguing with each other. We’re not slagging anyone off; we’re just lamenting. The only mission was, to be honest. It’s that wonderful feeling of people knowing where you’re coming from but not having to understand every word. Like you said, certain lines stand out for you. That’s the love of the game. I want to write in a way that impresses me. For anyone that’s creating, there’s that desperation for some sort of connection, for people to know where you’re coming from. We’re part of the world, not just a floating fart to f**king sniff at.”

Cal: “There’s a unity in just shouting into the void together. At our live shows, it’s seeing people being emotional. The fact that people are understanding the hope we’re putting across.”

Joe: “A lot of that’s the subtext though. We don’t really have a hopeful statement, we ain’t saying ‘throw your arms around each other’. We’re saying ‘look how sh*t everything is’. But if we can all see the sh*t there’s some hope in that.”

Keep up to date with the best in UK music by following us on Instagram: @whynowworld and on Twitter/X: @whynowworld