It’s been 30 years since Trainspotting and Irvine Welsh is back in Edinburgh. The city has changed – Leith-sur-Mer is the gentrified seaside haven it was threatening to become in the novel’s sequel, Porno – and the world has too, moving from the street-driven society Welsh captured so memorably, to one unfolding on screens.

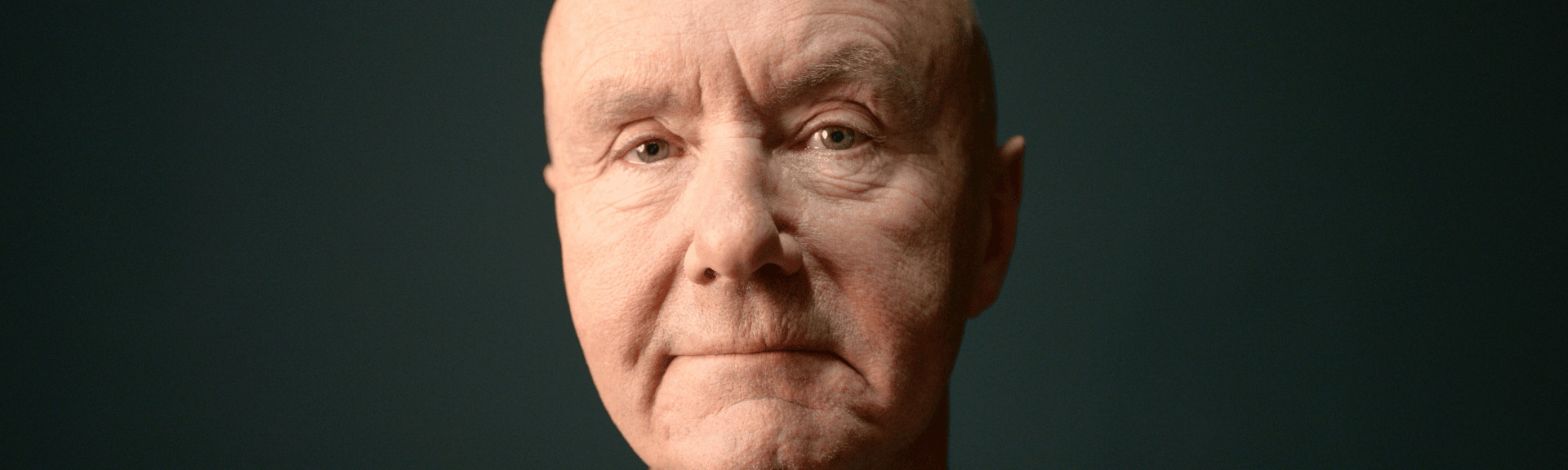

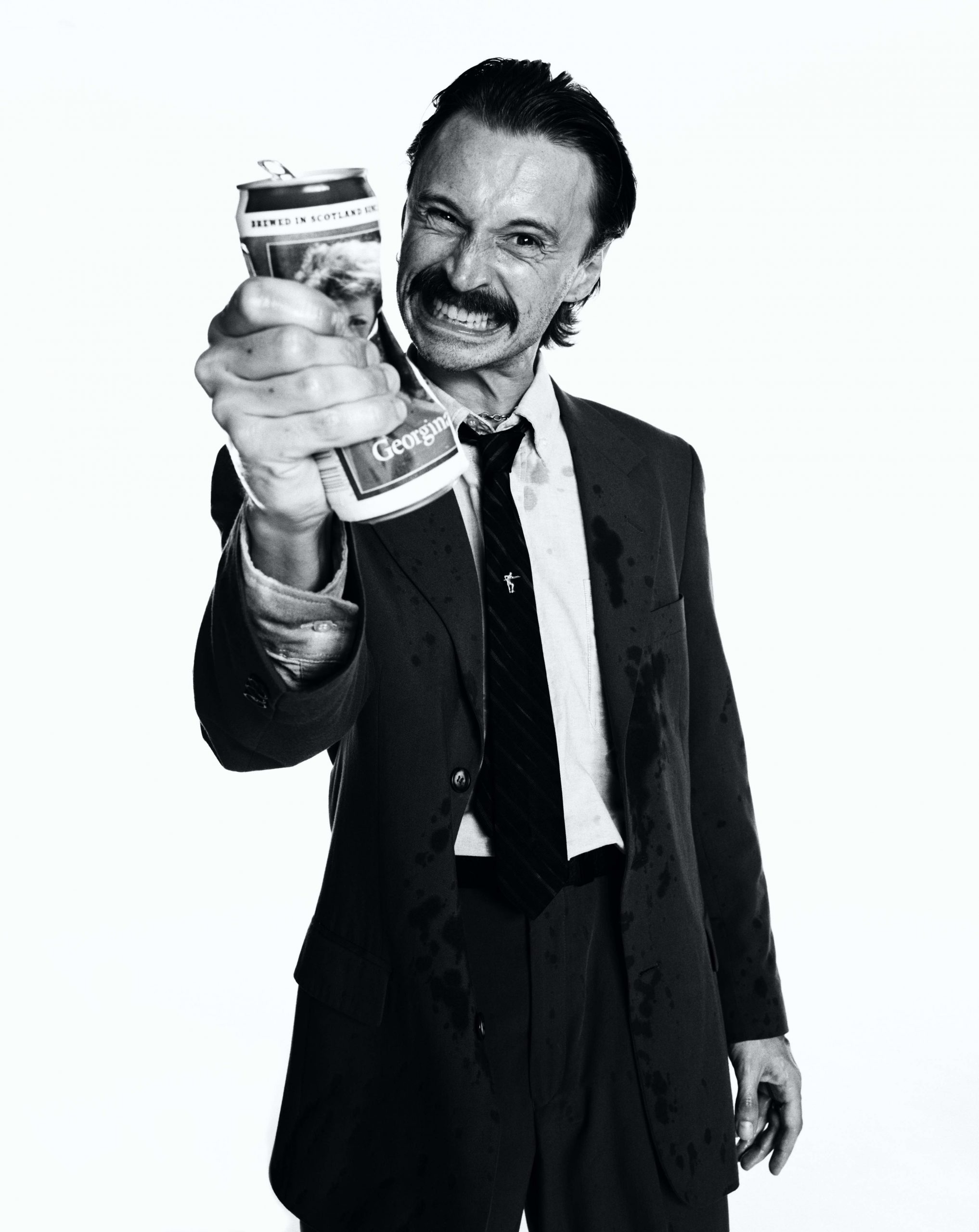

The changes undergone by Welsh himself might be most drastic of all, but he remains as outspoken as ever, a terminal side-effect of a self-diagnosed conceit. He is thoughtful on the consequences of Trainspotting and entrenched class structure, and amusing on forrays into music and drug-fuelled grandstanding come sunrise. He is also the subject of a pair of new documentaries, the first of which premiered this week at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

It’s called Choose Irvine Welsh.

“You write a book and it sells 10,000 copies? You’re a hero. You’ve represented your crowd and crew and all that. You sell 100,000 copies? It’s: ‘Yeah, good on you, well done, like.’ You sell 1,000,000 copies? You fucking sold out. The book is exactly the same. Not changed one bit.”

Irvine Welsh is slouched in a New Town pub, drinking a black decaf coffee. A conveyor belt of palatable 21st century pop tunes circulates over the speakers, drowned out by an extended family celebrating a young boy’s birthday on the other side of the room. Welsh knows the waiter and seems comfortable here. He is genial and smiles often. It’s a good smile, appearing slowly and unfurling in front of your eyes. We’re only a couple of miles up the road from his native Leith, from the schemes and seediness that played host to Trainspotting, but it feels far further away than that. Is this what selling out looks like?

“I think a lot of people felt like the story was theirs and it was taken from them.” Welsh doesn’t seem annoyed by the vague idea of selling out, but instead intrigued by it. “Taken by the world, by commerce. And I think it’s true, myself, but the act of writing is an act of giving away. You can’t give it away to people in particular. You throw it out there and see where it goes.”

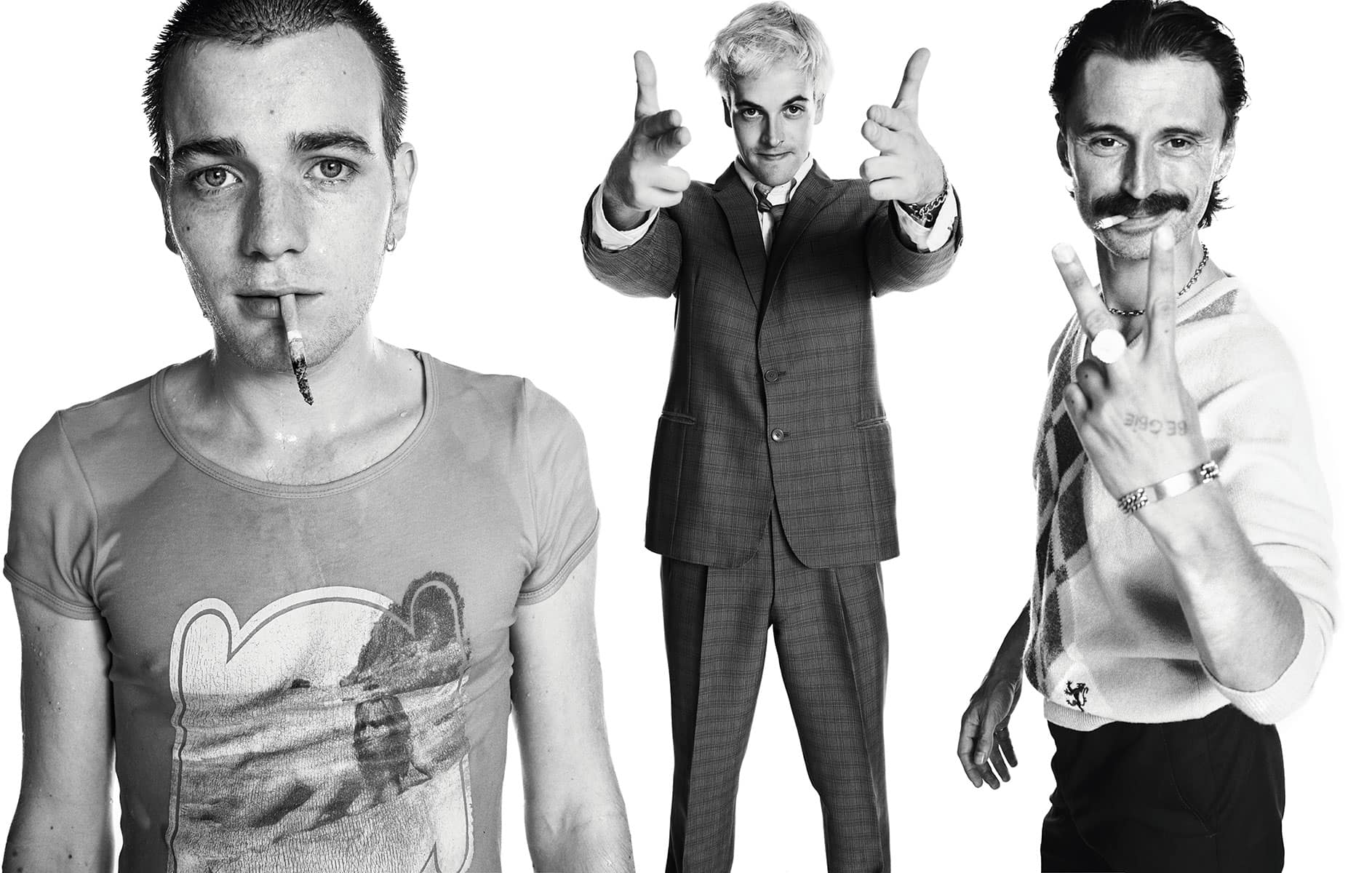

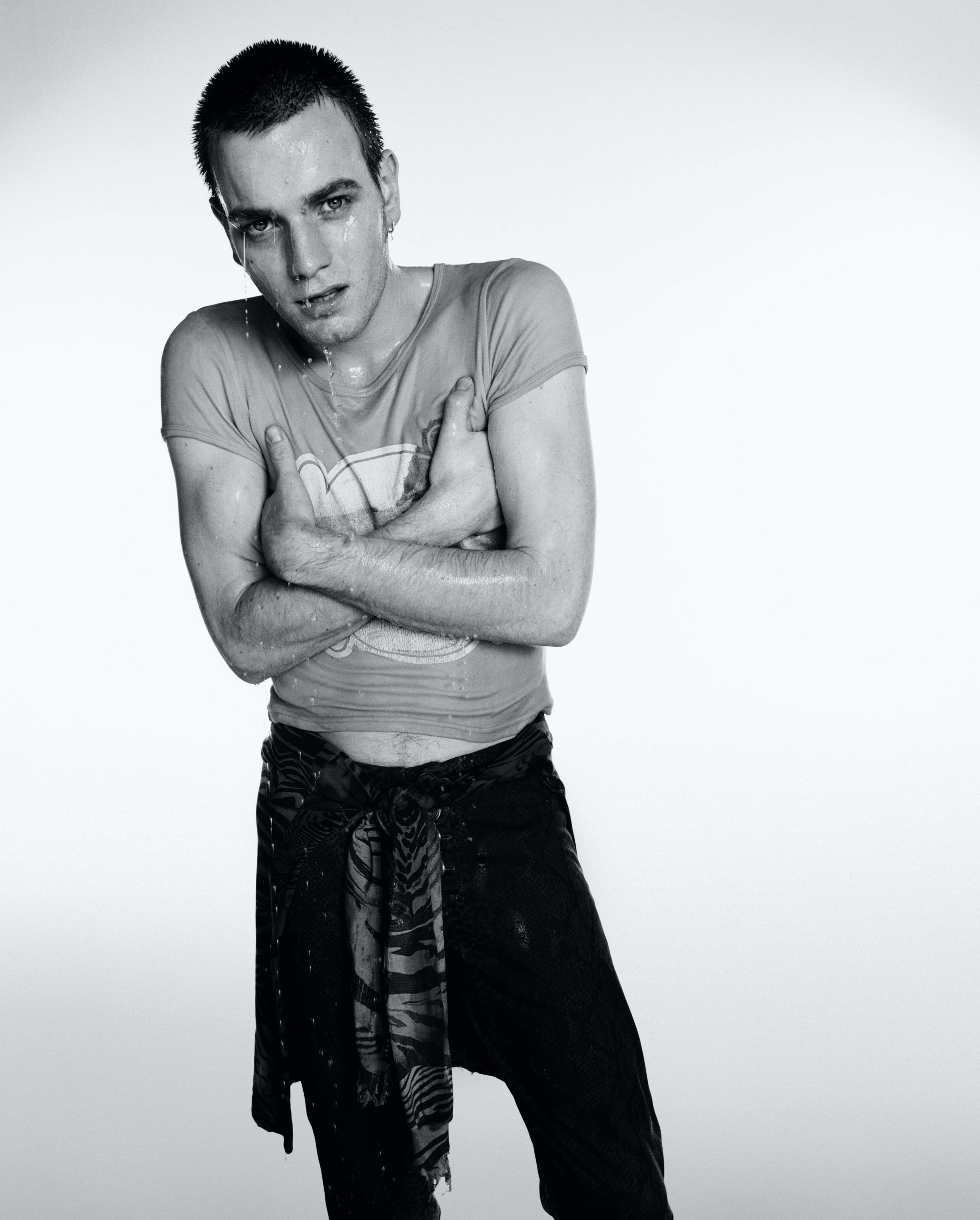

Ewan McGregor, Johnny Lee-Miller and Robert Carlyle pose as Renton, Sick Boy and Begbie from Trainspotting.

Trainspotting went everywhere. Welsh is sceptical if it would go anywhere today – casting doubt over if it would even find a mainstream publisher in the “political and almost posthuman landscape” that’s developed – but it caught fire upon release in 1993 and became a modern classic.

Welsh’s first artistic pursuit, his first act of giving away, was not writing, but music. “I was obsessed. I tried to get into terrible bands and I was always getting thrown out. I made all these tapes and sent them away to record companies and they never sent anything back. Constant rejection.”

A novel was, in Welsh’s words, a “last chance saloon of creativity”. What became Trainspotting was written quickly, Welsh then into his thirties but reflecting, unflinchingly, on a “disintegrating” 18 months of heroin addiction and club nights that had transpired a decade earlier.

Portions of the book were published in magazines and met with positive feedback. “I sent it off to the biggest publishing house in the country and straight away they came back and said: ‘We want to talk about this.’” Three decades, a dozen novels and numerous screenplays and short stories later, Trainspotting remains his seminal work.

This is partly because of the first film. For millions – myself included – Danny Boyle’s film adaptation was how we first met Mark Renton and company, and, therefore, how we first met Irvine Welsh; both as the grinning face of Mikey Forrester, but, more importantly, as the mastermind of the humour and depravity that stopped you in your tracks, maniacally laughing at you for choosing life while simultaneously demonstrating how fortunate you were to have unconsciously made that decision.

It’s partly because Trainspotting was Welsh’s debut; it got there first, and anything that followed in his distinctive style would be a derivation of it. The thick Scottish prose and unforgettable – almost scarring – subject matter was never going to greet you with a timid, Spud-esque ‘Awright’. Rather, it smacks you firmly on the back, like Begbie, and although your brain tells you to stand up, walk out of this dingy pub and leave this psycho to maim some other poor soul, he’s got you hooked and there’s no leaving now.

“I like to confront myself and really disturb myself,” he says of the shock factor. “I always have this thing, ‘What is my mum gonna say about this? What is my girlfriend gonna say about this? In really uncomfortable moments, if I don’t have that, paradoxically, I don’t feel comfortable. If there’s nothing in the book that makes people close to me think, ‘Who the fuck has this come from?’ there’s no real point in doing it.”

Trainspotting’s continued relevance and success is also in part down to Welsh returning to these characters. A sequel, Porno, was released in 2002 and is the basis for the follow-up movie, T2 Trainspotting. Welsh also wrote a prequel, Skagboys, containing some of the original material that wasn’t included in Trainspotting, and a final installment, Dead Man’s Trousers, arrived in 2018. The core cast – Renton, Sick Boy, Spud and Begbie – have all aged and developed in the 30 years as well.

“It wasn’t so much going back to these characters, it was getting away from them,” he reflects. “I’ve still got drawers of stories about them.”

Ewan McGregor poses for a portrait shoot as Renton from Trainspotting in London, UK. (Photo by Lorenzo Agius/Exclusive by Getty Images)

Welsh has his own view on why Trainspotting has stayed popular. “The reason it’s survived so long is because it’s not so much a youth or a drug book, as it is a book and a film and play about the collapse of paid work. What do you do after paid work? This is what everybody is facing. It used to be the industrial working class, who were agonised without question, but now it’s professional people, the journalists, the paralegals, even the lawyers who are being replaced by data.”

He is not the first, nor will he be the last, writer to comment on the technological revolution that has happened more or less identically in the years since Trainspotting, but it gives him a fairly interesting perspective on it. In 1993, less than 5% of British people had mobile phones. By 2000, that number was 50%. Trainspotting is not just a story set in a world before screens, but an account of people’s lives in a model of society that could, quite plausibly, be confined to human history.

Welsh philosophises with a blend of hesitation and conviction. There is no doubt in anything he actually says, but there is in the way he says it. Some of the lengthy tangents he can go on seem to unravel in his mind only split seconds before they arrive at his mouth. I expected a brasher, less wavering character. His arguments don’t lose any authority, if anything his musing inspires trust, but at times it can be hard to tell when Welsh is being sincere and when he is taking the piss. Often, it’s probably a bit of both.

Throughout his fiction, he uses humour to explore topics typically treated with gravity. “The more horrendous things get,” he smiles, “the more people will laugh and take the piss. We can’t change the world and our only defense is laughter really.”

Some of the most entertaining moments in Welsh’s work are the sweeping monologues. They are a feature of his writing, and given even more prominence in the films. “You do get people who tend to grandstand, particularly [in Scotland], especially when they’re coming down from drugs or they’re drunk and exasperated about something. They’ll give a big old soliloquy, a sort of pseudo-Shakespearean rant about the way the world is. I always find these things massively entertaining and so I like to get them down in print.”

‘Choose life’ is the most famous one. It provides one of British cinema’s best opening scenes and encapsulates the story’s energy. The same is true in T2, with Renton’s impassioned rant the climax of an inescapable emptiness.

He’s having a black decaf today, but Welsh still drinks. He went with friends down to Leith the other week in search of the cheapest Guinness (“£3.60 at the Dockers club”). He still takes the odd drug – though not heroin since he first got clean – and a documentary out in the coming months looks at Welsh’s life over the last 30 years through the lens of a DMT trip.

That is the second and more “off-the-wall” of two documentaries coinciding with the anniversary. The first premiered this week at the Edinburgh International Film Festival. Directed by Ian Jefferies and featuring interviews with some of the other men instrumental to the social phenomenon of Trainspotting – Danny Boyle, Iggy Pop, Ewan McGregor and Robert Carlyle – it also sees Welsh himself reflect on his journey from Muirhouse to Miami and beyond.

Robert Carlyle poses for a portrait shoot as Begbie from Trainspotting in London, UK. (Photo by Lorenzo Agius/Exclusive by Getty Images)

“I went out for a pint of milk and came back ten years later” is how he describes moving to America. Though he primarily lives between Edinburgh and London, Welsh still has a house in Miami and has spent much of the last three decades on the other side of the Atlantic. Chicago, San Francisco and Miami have been permanent homes, with New York and Los Angeles western entertainment capitals. “I had no plans to go, but I got married over there and started to pick up work.”

He says Leith is still his favourite place in the world. He still talks in a thick Scottish brogue. His defence of the working class still appears in broadsheets. Inevitably, however, if you split Welsh’s life into binary, pre-and-post-Trainspotting eras, they must be transformatively different.

People can say “sell out”, but it is an abstract and rather meaningless accusation. More interesting, in my view, is asking if he can simultaneously be an anti-establishment provocateur with confrontational art, and a multi-millionaire jet-setter who could, if he really wanted, retire tomorrow.

“I completely agree, to an extent. It’s the price of…” Welsh has paused before, but here he hesitates for the first time in more than an hour, before changing tack. “It’s a weird thing, you know. You want to stay the same at your core, you want to maintain your core values and your core sense of self, but you also want to grow and develop and make the most of the opportunities you’ve had, and I’ve had a lot more opportunities than most people from my background.

“So many of my pals, when we go out we’ll wind each other up, you know, and they’re all focused on how much I’ve changed. I also make the point, though: ‘You guys have changed as well. You guys are moving pictures. You’ve grown a lot, you’ve been places, you’ve done things that have made you very different as well.’ Because I’ve been in the spotlight, I suppose it’s been a bit more visible.”

Welsh’s outward ‘change’ and domestication is perhaps even more pronounced to us, strangers, who never actually knew him before. Readers and viewers ascribe the extreme actions of Trainspotting’s characters onto their creator, desperate for these lunatics to be semi-autobiographical, and, therefore, at least somewhat true. People chose the characters he created. Now we’re being given an opportunity to choose him.