De La Soul might well have been too creative for their own good – too creative, at least, for the modern music industry. Their wildly freewheeling approach to sampling other people’s music is one the cornerstones of their influence on the music that came after them.

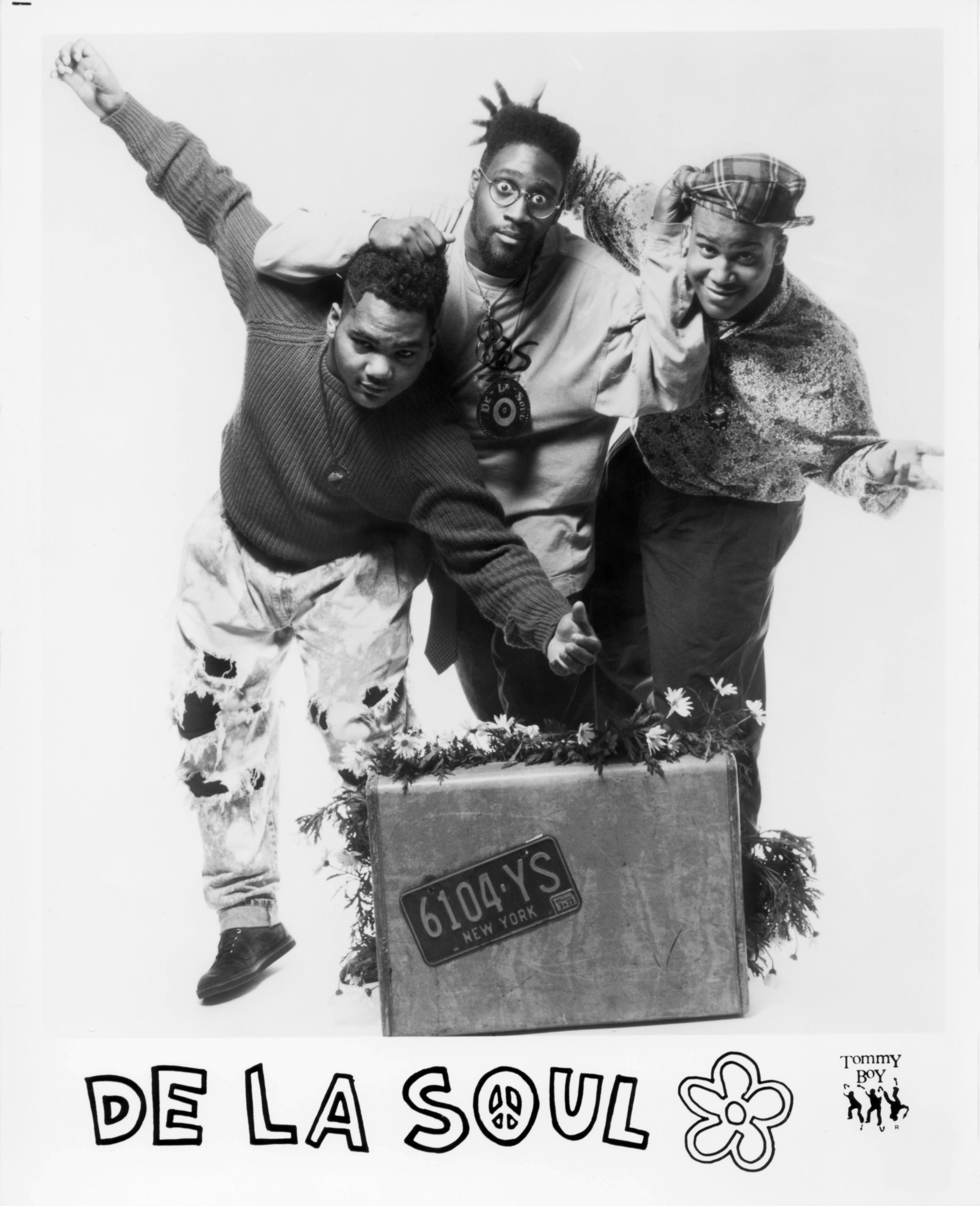

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives

When they emerged, as seemingly fully formed, original geniuses in 1989, this didn’t matter so much. But with the ever-increasing litigiousness of the contemporary music industry, complications around sample-clearance, music publishing and other legal issues have kept most of their catalogue off streaming platforms, and hence out of the public eye and whole new generations of millennial and Gen Z listeners.

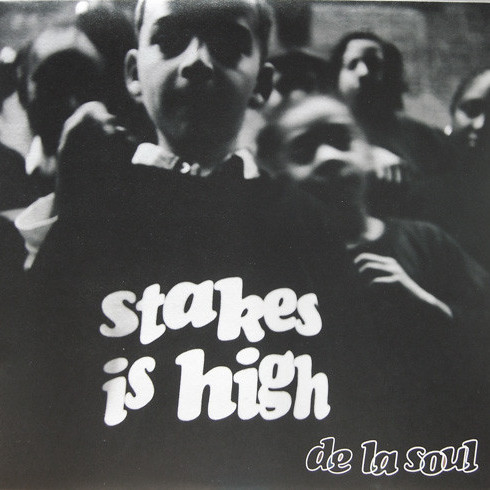

On 3 March 2023, however, that changed. A year of renewed negotiations to clear streaming rights followed many previous battles with their original label Tommy Boy Records, acquired in 2021 by Reservoir Media, who restored De La Soul ownership of their music and worked alongside them to bring it to digital platforms. Every De La Soul album is now streaming – most crucially, their legendary first-four-albums run, from 1989’s debut Three Feet High and Rising to Stakes is High in 1996.

It’s a somewhat sobering reminder of the reality of accessing musical history today. While we now have instant access to recorded music history, the decades-long travails of De La Soul show that – legacy artist or not – if you’re not on streaming, as Vincent Mason of the group recently put it, it’s almost “like we were being erased from history”.

In a sense, this sudden resurfacing of arguably the most influential rap group in history is a strange, increasingly rare kind of phenomenon. Hopefully it may have something like the creative effect on younger listeners as the posthumous re-emergence of more ‘cult’ artists, from Robert Johnson to Nick Drake. If my personal querying among the young is anything to go by, many of them have never even heard of De La Soul – familiar though they might be with fellow group out of the East Coast-based Native Tongues collective, A Tribe Called Quest. It’s an exciting prospect, because De La Soul’s music sounds as fresh as it ever did.

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives

A massive cloud hangs over this cause for celebration, though. On 12 February, one third of De La Soul – Dave Jolicoeur, aka Trugoy the Dove, aka Plug 2 – died aged 54, from congestive heart failure, with which he’d struggled with for years. This premature loss would be devastating at any time, but, as groupmate Vincent ‘Maseo’ Mason wrote in a tribute letter to Trugoy, doubly bitter is “the fact that you’re not here to celebrate and enjoy what we worked and fought so hard to achieve.”

In their respective letters, Maseo and Kelvin Mercer (aka Posdnuos, aka Plug 1) both acknowledged Trugoy as the guiding light of the group. “Thank you for never wanting to compromise the quality of our brand,” Mercer wrote. “Thank you for helping us become a group that will remain etched in the timeline of hip hop culture.”

De La Soul are, most definitely, as important to the timeline as anyone you could name. Everything about their appearance on the scene in 1989, their sound, lyrical approach, visual style, their attitude – their clear difference to any group of rappers before them, made an instant impact. Much like their innocently omnivorous approach to sample use, though, it was an image which the group would come to have a frustrated relationship with.

Like The Beastie Boys (who released their own sample-heavy masterpiece, Paul’s Boutique in 1989, the same year as Three Feet High and Rising), De La Soul began as a tight trio of high school buddies. Hailing from Amytiville, Long Island, they were close enough to New York to soak up the hip hop sounds coming out of the city, but suburban enough to be restless, irreverent, and disaffected.

Photo: Sergio Dionisio

They began making demos together, including ‘Plug Tunin’, which appears on Three Feet High. They played it to classmate DJ Prince Paul, who was already working in New York, who reworked it, tidied it up, and got De La Soul signed to Tommy Boy Records. Having made only a handful of demos, the group immediately started putting together one of the most innovative records, not just in hip hop, but music history.

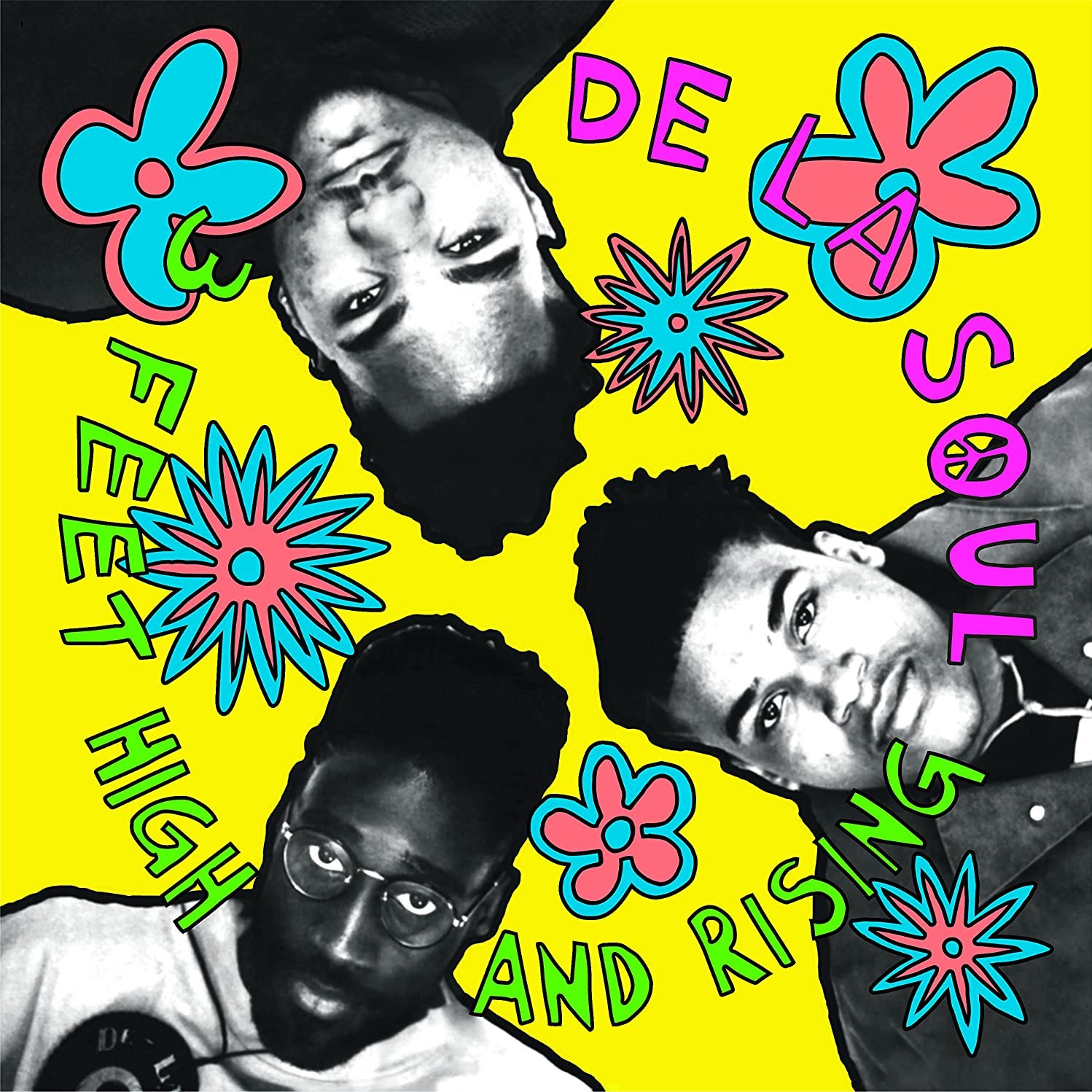

Again, like the Beasties, who were spending their days chilling and playing records in Rick Rubin’s college dorm room about the same time, Three Feet High and Rising, produced by the musically omnivorous Paul, emerged out of a white-hot and giddy period of crate-digging and wildly eclectic record-flipping. Along with drawing from classic soul, funk and jazz, they dug into old country, (Johnny Cash and 1920s yodeller Jimmie Rogers show up), Billy Joel, Hall & Oates, Eddie Murphy sketches, and French language instruction records.

The record has its own madcap kind of concept structure, introduced, and interspersed by absurdist game show skits, in which we hear pearls of wisdom such as: “Everybody in the world: you have dandruff”. The ‘concept’ isn’t annoying: it all adds to the general sense of fun. With every album through to Stakes is High, they structured their albums around ‘Intros’ and constant skits. De La Soul indeed pioneered a more cohesive, total approach to the making of hip hop records, an approach which has resonated down the years to contemporary artists from Childish Gambino to Kendrick Lamar.

And it all just comes together, comes off, dances off, perfectly, on Three Feet High and Rising – the pure sound of unleashing exuberant youthful creativity (they were all still in their teens), all while just playing around with your friends. Their approach to lyricism brought in disjunct cultural references, sensitive introspections, and private word-games impenetrable to anyone but the band themselves.

Photo: Scott Gries

This is quite apart from the cleverness and beauty of so many phrases, particularly those of Trugoy, who announced right out of the gate in ‘Plug Tunin’’ that he and De La Soul were all about “a new style of speak”, one where “vocalised liquid holds the quench of your thirst”. From music to lyrics, De La Soul put so many ideas together that they could leave listeners puzzling, and dancing, many years down the line.

However, the group soon found themselves hemmed by the record industry’s attempt to cash-in on – and public expectations of – their chilled, ‘hippie’ image. The pigeonholing contained more than a little unspoken racism. Though the group were happy to stand against stereotypes around young Black men which had been propagated in response to the ‘violent’ or ‘macho’ gangsta tropes that came before them, they were only ever interested in being themselves. “We’re just peaceful guys, so we like to wear peace signs in our hair,” said Pos upon the release of Three Feet High, “but we’re not psychedelic rappers, and we’re not hippies.”

In one of the cringiest examples of the record industry’s attempt to present them as a ‘safe’ rap group that it was okay for white people to like, was a 1989 promotional campaign showing a suited yuppie type, reminiscent of Jim Carrey as Truman, clutching a copy of the record: “I Came in for U2 – I Came out With De La Soul”, it reads, and underneath a quote from the LA Times: “The Sergeant Peppers’ of the 80s.”

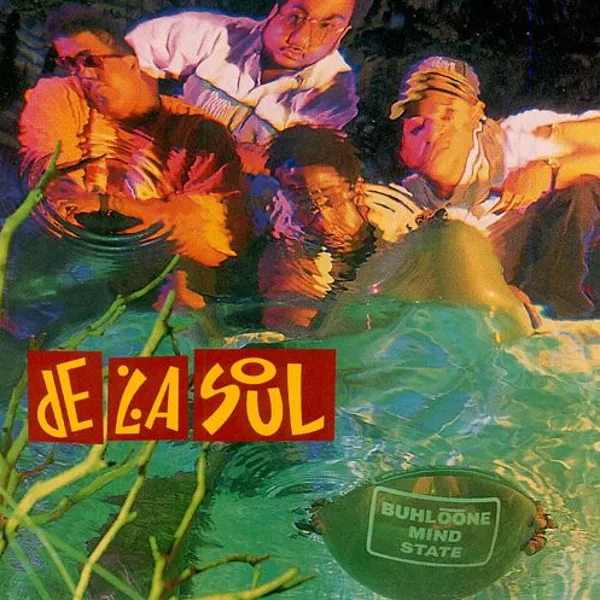

The design for Three Feet High was, at the time, a radical statement: cartoony, poppy, colourful, festooned with the famous daisies which the group would come to hate, and symbolically smash in a flowerpot on the cover to their provocative sophomore masterpiece, 1991’s De La Soul is Dead. Here, the concept-skits revolve around a group of bullies stealing the record from a younger kid and mercilessly mocking on all the songs. It’s a move which would be out there even today, and it signalled that De La Soul would be kowtowing to nobody’s idea of who or what they were.

Photo: Scott Gries

Feeling their identity was being whitewashed, the group began the process of constant striving for independence that would define them. Continuing to refine their approach musically and lyrically, each album that came through into the ‘90s would sound different and fresh, such that there is little consensus among De La fans as to what the ‘best’ of their albums really is, though they will always likely be defined by their 1989 breakthrough.

And they’ve never lost it: both their 21st century albums, 2004’s The Grind Date and 2016’s …and the Anonymous Nobody (which was crowdfunded by fans after the group went label-less) are distinct additions to the catalogue, enjoyable and worth revisiting. Now that all their albums are in one place and just a click away, it should be hoped that the fierce intelligence, exuberance, and independent spirit of their musical legacy can reach a new generation.

Featured image: Matti Hillig.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.