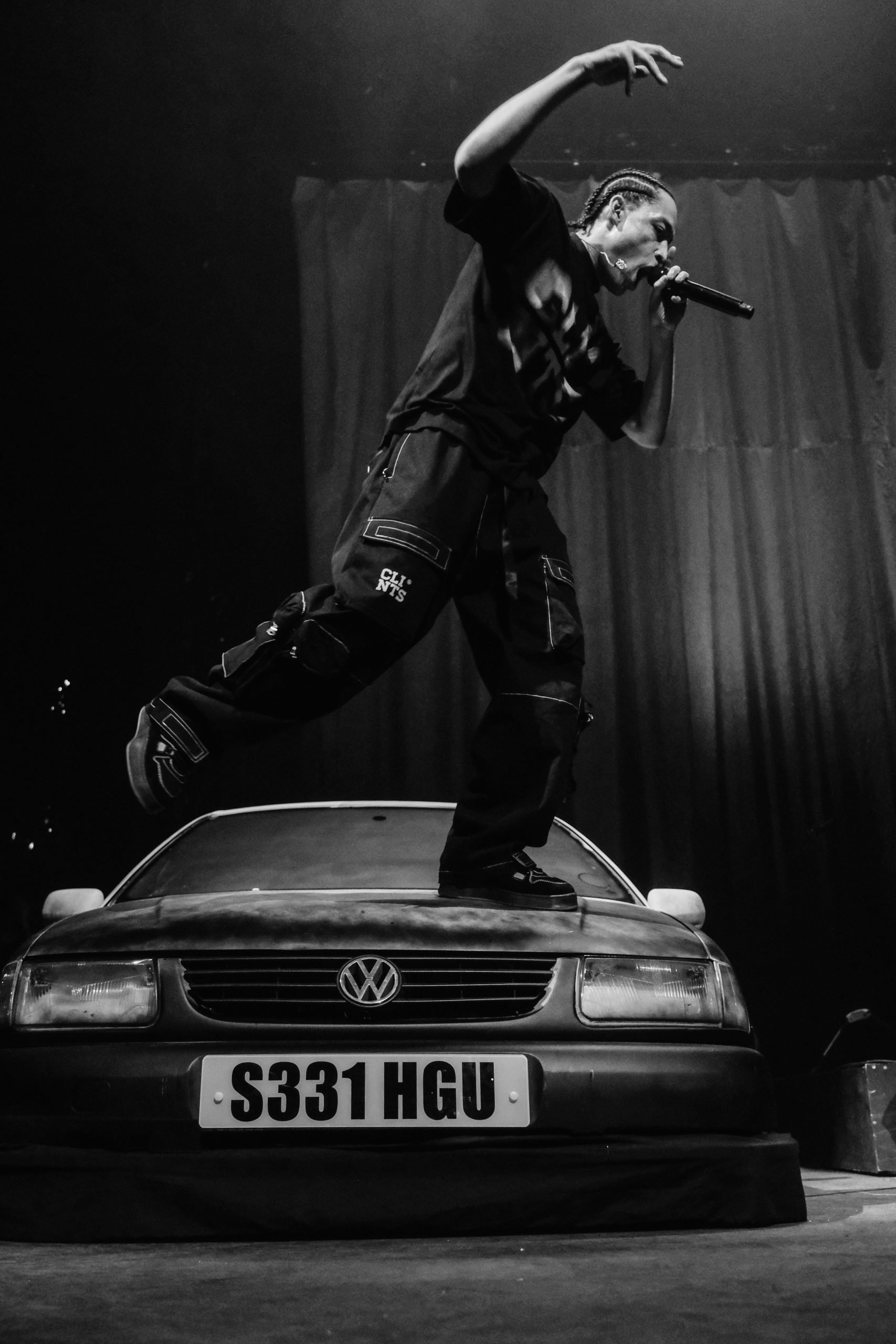

It’s unsurprising, then, that at the London rapper’s Wembley Arena show last week, half a replica of the car sat on one side of the stage as a streetlamp leaned over on the other, the lights of both flickering in near-perfect response to the varied tempo of the setlist. Neither were situated too obviously, but seemed a natural fit, as Loyle Carner’s impressive band accompanied him on varied levels across the stage. An outfit that could play it large when required and then distil it down to just the main man himself during periods of quieter reflection.

Photo: Karolina Wielocha

All in all, it was a show that breathed and – unlike many shows where an ending isn’t known until the house lights come up and security usher you out – it had a cohesive narrative arc, from the blistering opener of ‘Hate’ to the forgiveness of ‘HGU’. (Yes, there was an encore of fan favourite ‘Ottolenghi’, but the resolution had been cemented before).

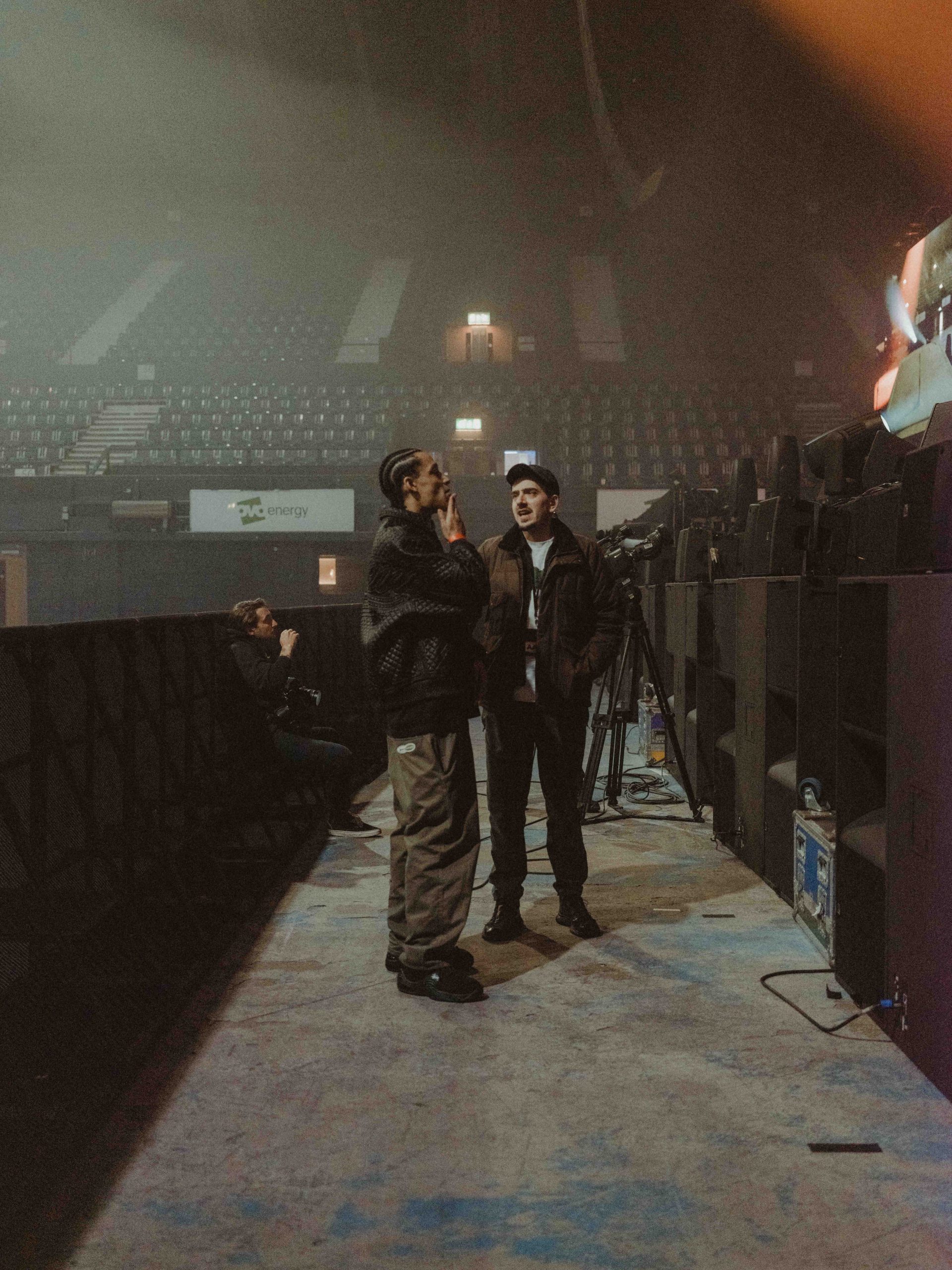

We speak to Harrison Smith and George Thomson. This creative direction duo make up The Unlimited Dream Company, who worked with Loyle Carner to bring the vision of his show to life for the stage at Wembley and smaller, more intimate venues across the country.

Photo: Karolina Wielocha

Congratulations on the show. Talk me through what the early process is like working with an artist and how you go from the initial idea to the stage.

Harrison Smith: It’s quite a varied process and depends on the artist and their creative outlook. With Ben [Loyle Carner], specifically, he’s a really visual person who exudes creativity through his music, and he’s drawing constantly. When we got approached, there was a selection of mood boards and a creative brief that explained his album [Hugo] to help us on his journey. We always say we like to work with people that already have a story and a message and translate that for the stage, so the audience can understand it in the live environment. We actually had one of our own shows on his mood board. He said, ‘I really like this show’, and we told him that was us.

George Thomson: That was a good time. It always works best when the creative process is a dialogue, and you’re not just going, “Here’s something, do you like it?” Instead, you build it together, and it grows. Ben just felt like part of the design team, really, workshopping through ideas, sketching things, modelling things. Some clients don’t want to see too much. They just want to know what they’re getting and not complicate it; but in his whole music-making process and everything he does, he’s very collaborative and likes bringing people together, so he wanted to see everything–

Photo: @felixaaa

HS: And understand the reason behind the decisions that were made. A lot of the time, me and George will go through 1000s of iterations and make small, incremental decisions – then we might present three versions [to the artist]. But with Ben, he wanted to know how we got there, so we’d show him almost all the drawings and the journey – why we went for this way, stylistically, or why we didn’t just want the full car onstage, for instance.

You mention the car – obviously, that plays a big part as an image in the album, Hugo. Was it always the obvious thing to do, to have it onstage?

GT: Weirdly not. It was a less-is-more approach. With his music, Ben likes to find what works with the most minimal parts rather than maximalist chucking loads of things in and hoping it comes together. It was about how we could make the most impactful story with as few elements as possible. For ages, we talked about not having the car – it might have looked a bit obvious, but it might have fallen into musical clichés.

Photo: @felixaaa

Then, when we started to develop the design with this gradient coming out of the stage floor, we had this treatment where we realised we could see the car differently, and it could be a more subtle lighting tool. During the regional shows, we thought to help link the story together. We felt we were missing the final piece of the puzzle that tells the audience what that story is and creates that nice moment where [Loyle Carner] can explain what the car is.

That’s an interesting point about it not falling too far into the theatrical. How did you find that balance?

HS: With that element, it was about creating an overall aesthetic that made it more of an art installation in its minimal, core form. The main brief of what we tried to achieve was stripping it back. It’s built around this whole world of the album concept – his journey with his dad, as a man, as a father. [We had] the whole stage design as a vanishing point, with the sun coming from the centre and these layers of all the different parts that we build up and then stripped back to their core form. But we didn’t want it to be too on-the-nose, like, ‘Oh, there’s a streetlamp, let’s put some trees on the stage and a park bench’. We were more trying to create a feeling and an atmosphere.

Photo: Karolina Wielocha

GT: With the car onstage, others might have gone down the route of having an actual street scene around it and props that look real. That would have rooted you in one moment, and it’s quite fixed, but because we had this gradient coating everything, it creates more of a canvas, and then we can paint with light onto that, and create completely different moods, revealing things and layering up the story.

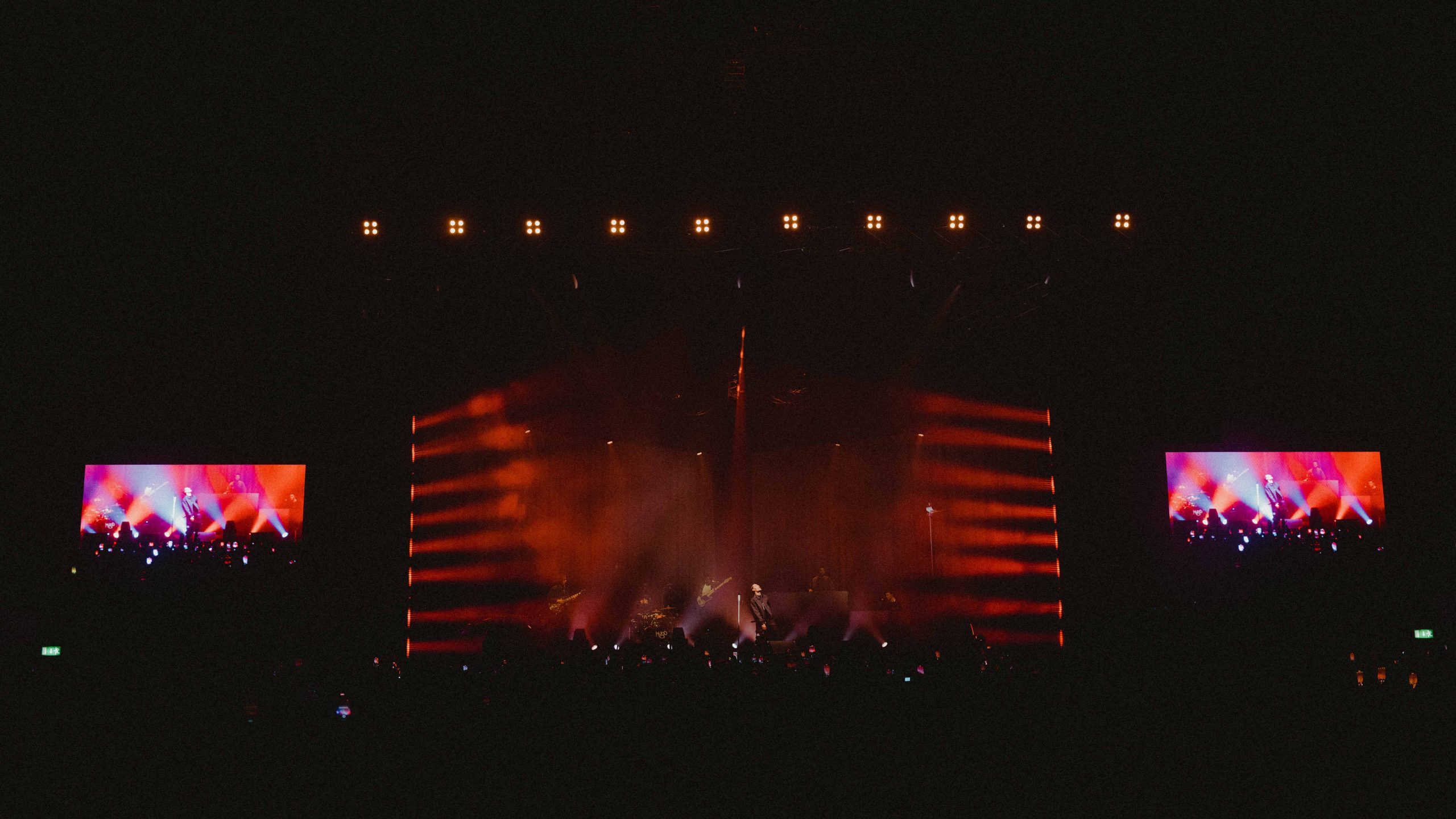

With everything we do, we like to see tension as a hand-crank: you wind everything up and up, and then let each bit go one-by-one, slowly, over the course of a show, so you’re not just giving everything upfront, and then by the midpoint of the show, you’ve seen everything. It’s about ABC storytelling – a beginning, middle and end structure, and holding as many points back to articulate those moments in the show.

Photo: Karolina Wielocha

Of course, Loyle Carner doesn’t just play tracks from Hugo on his setlist, but that album, in particular, has its bigger moments on tracks like ‘Hate’ and ‘Nobody Knows (Ladas Road)’, and then its far more intimate periods like ‘A Lasting Place’ and ‘HGU’. How did you devise a set that could match both?

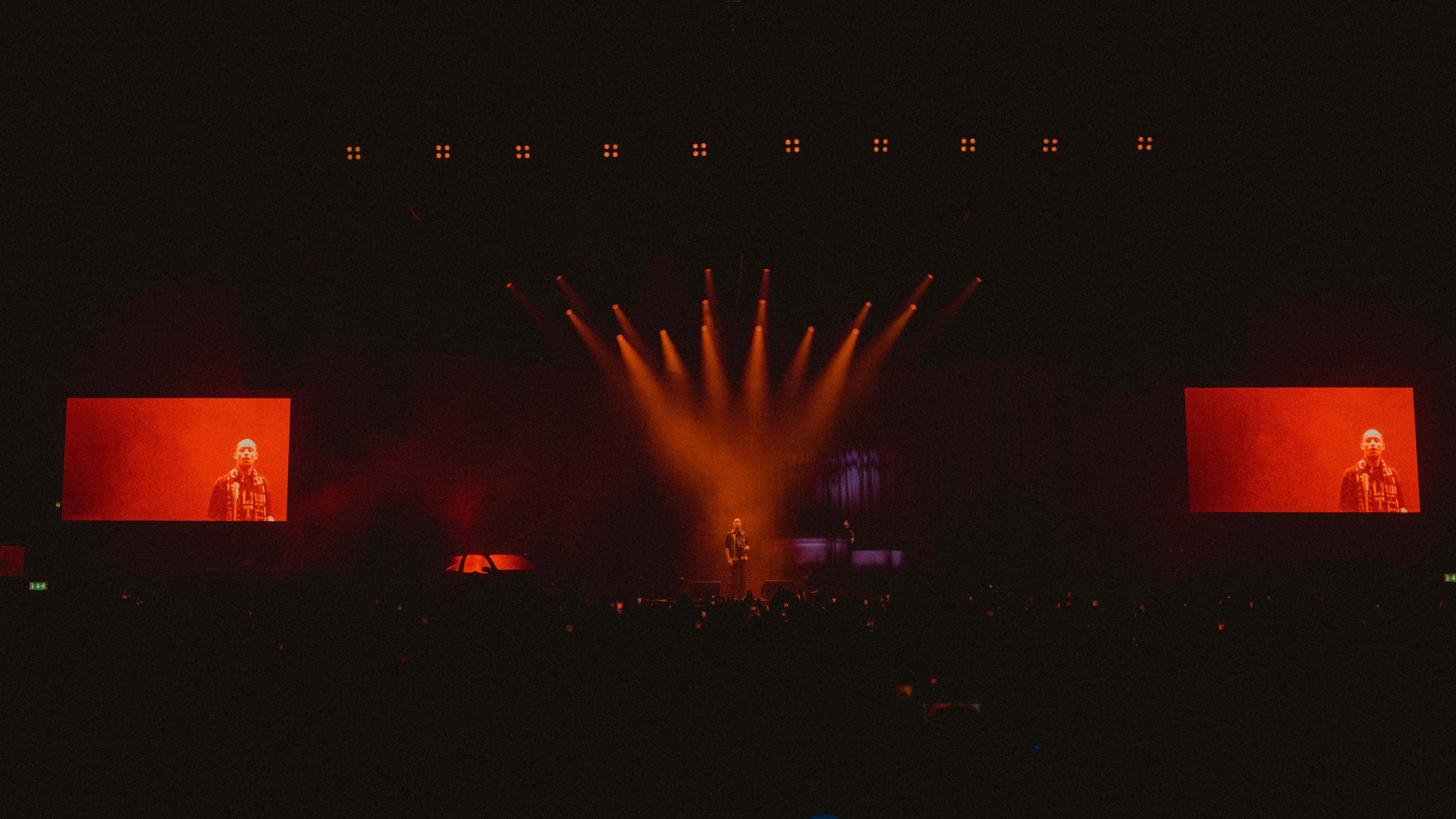

HS: We wanted to create different levels of the band because part of the brief of this sort of tour was the live element for him. Ben’s such a lovely guy, and him and the band are like a family; when they’re performing together, they’re just jamming out, having a good time. Ben loves the band as much as they love what they’re doing, so we wanted to create levels and space that gave him options. We never said, ‘Okay, stand here for this moment.’ It ebbs and flows with what worked with his idea of the setlist, from the inception of ‘Hate’ to the final track ‘HGU’, of forgiveness, that brings you to the end. There, he’s alone, the band members slowly leave, and he’s in this quite stark, white light, isolated, telling his story.

Photo: @felixaaa

GT: It was interesting working with him because he’s one of the most important storytellers of his generation. Having someone who’s already conceived an album with such a clear structure to it; that sense of an emotional journey being reflected on the stage gives you that direction. The overall concept was to convert that emotional journey into a 12-hour day cycle: the light begins with this red, dusk dawn, setting on anger; then comes the reflection of the night as you process information and come out into a new day. Because Ben gave us that very clear emotional journey, like a film script, we could match that conceptually with everything we were doing, and it gave us that backbone for the whole show.

Absolutely, Hugo has a very cinematic quality to it… What were some of your biggest challenges in putting this show together?

HS: The toughest part for us was the modular design. We designed for Wembley knowing it’s the biggest show, so we wanted to get the details in on a scale that really filled that room. But we knew it also had to fit around the country in various different sizes, so it was about coming up with a design that was flexible enough, in more technical aspects, that it could still fit in everywhere on the road – and not feel like a Wembley show squeezed into a small space–

GT: Or the other way round: a small show on a Wembley show.

Photo: Karolina Wielocha

Were there any other shows you’d worked on that this one reminded you of or your use as a blueprint?

GT: I’d say with everything, we start the process as soon as we start talking to the client. We wouldn’t reflect on what we’ve done. We just take all their input. But if it was similar to any show, the show [Loyle Carner] referenced was a show we did for Obongjayar at Koko, which had a balance between the theatrical and a very clean aesthetic. It had a very clear narrative as well. That said, we have an approach to design, but we wouldn’t say we have a style; we follow our method and how we like to work, creating the result. At the beginning of this process [with Loyle Carner], there wasn’t anything in my head for how it would look. It was just about going on that process with Ben.

As you said, Loyle Carner’s been a prolific force in the UK for several years. Like many people, I’ve been following him for about a decade. His Wembley show seemed like a massive step up in his confidence as a performer. What do you think having a production value of such quality does for the performer and the performance?

HS: It’s an interesting one: because of the stage design on the regional tours and the smaller venues, it was a slow increase in capacity. He was elevated to Wembley and held the crowd well with that many people. And in all the different venues, he held it differently, which is articulate of him as a performer. And the band still felt together, like a family, and they were all levelling up, too, but it’s steps, rather than a jump.

Photo: Karolina Wielocha

GT: You can definitely swamp a performance in production; you put so much around it, it ends up engulfing everything in its path, not allowing the show to breathe. The first thing for us is always the music. Everything else is secondary. Everything we do is about elevating the music, so the first step is plotting out the band in relation to Ben and getting that shape where they still feel like they’re in their rehearsal space together, with the same dynamic, the same energy, and then everything else is about trying to lift that up. A big part of it is those peaks and troughs: bringing everything back down again, and it is still just being Loyle Carner and the core of what it is, which is a very personal story.

It strikes me that you’re not imposing ideas on artists as creative directors but allowing their visions to come through. Do you see yourselves as a mediator between the artist’s vision and the show?

HS: Yeah, it’s all about the approach and the creative problem-solving within that. We always get delivered constructs or boundaries, and people apologise, but we thrive on that, about what we can’t do.

Photo: @felixaaa

GT: What makes it fun is, rather than just free expression where you can do what you want, we like having those constraints, those logistical problems – and correlating all the aspects of the show together to create a very tight, well-articulated concept across of the artist’s output. And doing that collaboratively, so it’s not just the artist and then us. You get a much better output if the whole thing is collaboration; it’s not top-down. Everyone can kind of input, everyone can express their opinion, and then you get the best out of everyone because everyone’s invested in it. We love the process, we love collaborating, and this is an amazing industry to be able to do both of those things.

It’s quite remarkable that you founded The Unlimited Dream Company in 2021, and already you’ve worked with Skepta, Slowthai, Alicia Keys, and obviously Loyle Carner now, among others. What’s your secret? How do you keep getting these good gigs?

HS: We’re not sure, actually!

GT: We’ve got a good agent… I mean, for us, the music has to come first. We have to love the music we’re working with to respond to that creatively, and then everything flows from there. We could have worked with other big acts, but it has to fit with how we like to do things. First and foremost, it’s the process we enjoy. It’s not about how many jobs we can win.

Photo: @felixaaa

And finally, is there a particular artist or an album you dream of bringing to life for a show?

GT: We have this conversation daily. We have a list that’s about 64 people long… We never want to be bound by genre. The important thing is storytelling. For me, I mainly listen to hip-hop, but I’m really curious about doing a metal show just because I’ve never worked on one. It’s got such a big production. It’s got very similar energy to drum n’ bass shows. That intensity, I think, would be wicked – something we’ve never done before.

HS: We’ve spoken about people like Metallica or Kiss, where they’ve got like cranes going around the shows. That’s just where my head’s at.

Well, Metallica have an album coming out in April, so maybe that’s the time to jump on it – if they’re reading…