It’s a warm evening just off Liverpool Street, on the night of the Champions League final. A brave date to hold a gig – especially when you’re scheduled to play between eight and half 10.

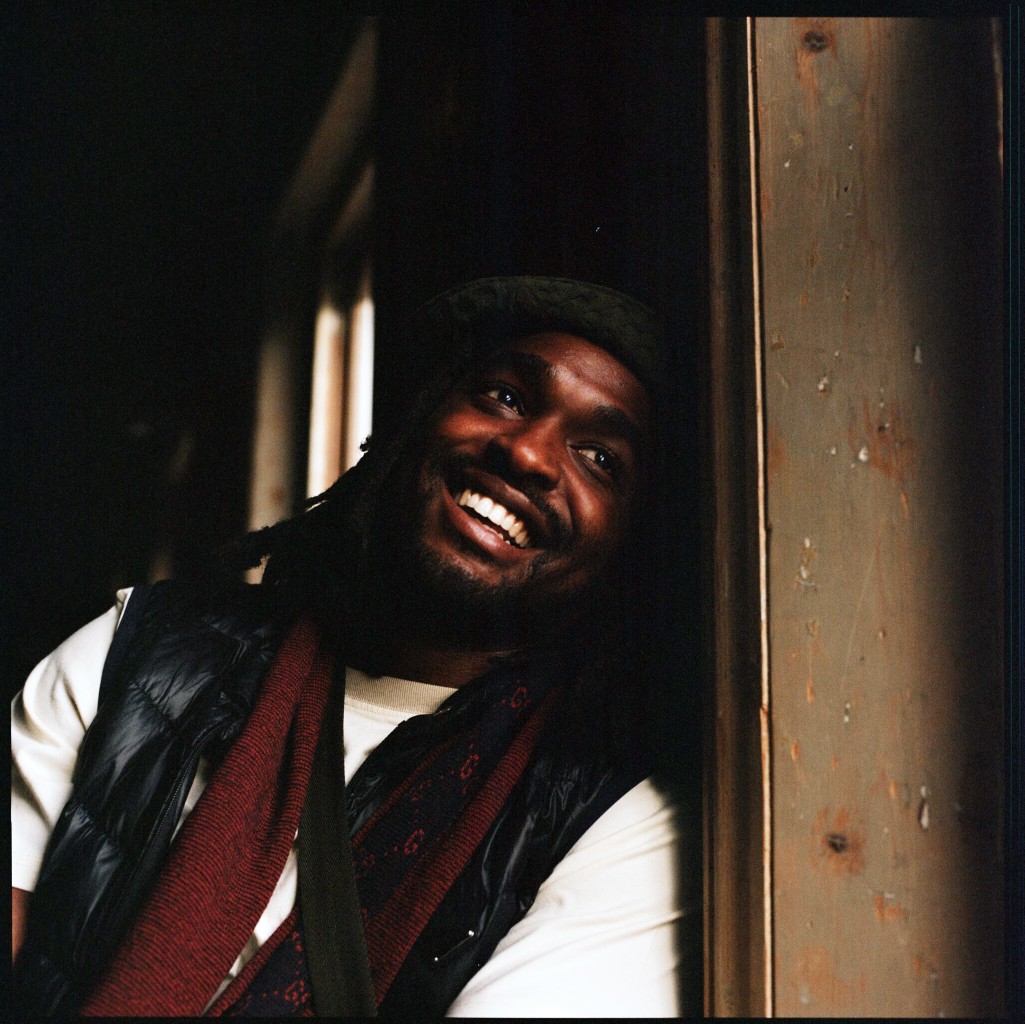

Yet such is the pull of Hak Baker, East London’s beloved son and self-described ‘G-Folk’ artist, that fans are packed into The Old Blue Last like sardines, their pints swaying to his stock of relatable tales.

This gig formed part of a series of pub shows, including at The Dublin Castle, The Windmill and The Social – all venues that, like Hak, are rooted in their local areas. Anyone already familiar with Hak Baker, knows he’s East London, born and bred; specifically, the Isle of Dogs.

“I don’t think you could wish for a better childhood, really,” he tells me, a couple of hours before his performance. “As a kid you could have fun, run about, there was places to explore. You could expand your mind… it was the people. There was morals, there was space, there was love, there was–”

Well-timed, Hak’s mate Bill, who DJs during parts of his set, politely interrupts to ask Hak if he’d like to get some food from another London staple: Morley’s Chicken. By all means, take your time, I say, as Bill hands him his phone. “I’m not very good with options – it fucks me up,” Hak says, as he scrolls through what’s on offer, taps the phone a few times and hands it back.

Obviously, my next question is to ask what he went for. “Three BBQ wings, three spicy wings, chips and a drink. I wanted a burger but nah, they wanted a bomb for it… They’ve got KFC prices. I don’t know who they think they are.” His chicken-winged compromise seems a wise one.

Anyhow, you were saying, a sense of community…

“Community. That’s the first word. Spirit. Togetherness. Doors open. You can open your mate’s door and walk in, see his mum, say hello, see who’s upstairs.”

Amongst this and a love for lyricism, Hak began his way into the music industry as part of the grime collective B.O.M.B. Squad, and was just 14 when their debut release reached No. 1 on the Channel U video charts.

“It wasn’t even called grime back then,” Hak recalls. “It was just something we did religiously – go to the youth club and MC. That was the thing. I remember seeing my mate Proof, a couple of other lads – Tyrone, Trim [who later joined Roll Deep] – in a fucking youth club after school, MCing. I didn’t know what it was, I just knew I was immediately obsessed.

“I went home, got a piece of paper, and just started trying to write lyrics, thinking ‘I need to do that.’ And the youth clubs aided us, which they don’t anymore – we could go there three days a week and MC.”

What happened to B.O.M.B. Squad is a tale as old as time. Put simply, “life got in the way”. Looking for more serious ways of making money, MCing – especially when grime wasn’t as mainstream as it is now – no longer appealed to many of the group, most of whom had left their parent’s homes (something Hak also did around the age of 14).

Hak also had some run-ins with the law – which he mentions in a few tracks – and ended up in jail a couple of times. For many, this might spell the beginning of a vicious cycle, but a moment of serendipity gave Hak a helping hand. “Basically a governor come on the wing and said there was these guitar lessons. I’ve always loved guitar music. I was obsessed with Kings of Leon at one point. They’d said whoever’s interested, write your name and put it in a hat, basically. And my name got picked up.”

“So we used to do these guitar lessons with this geezer every fortnight. I was 19, 20. Then he stopped coming and I just had this guitar, so I said to myself, ‘I’m going to come out of jail and I’m gonna play guitar. I’m gonna do something with this.’”

It wasn’t plain-sailing when Hak left prison, though. “I went back to what I knew really, to make money,” he says, recounting how he slept on his brother’s sofa at the time. He hadn’t even bought a guitar, let alone begin to fulfil the dreams he told himself. Then came – not serendipity this time – but an act of kindness.

“I started going out with a stripper and she had her head screwed on. Her name was Eliza. I’ll never forget her. She said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘What do you mean, I’m just doing what I need to do.’ She said, ‘Nah, you’re 24, 25. This is dead. You need to do something. What do you want to do?’

“I said, ‘you know what? I want to sing and play guitar.’” She said, ‘How are you going to do that? You can’t even buy a guitar, you ain’t got a bank account. You know what, I’m gonna buy you one.’ And she did.

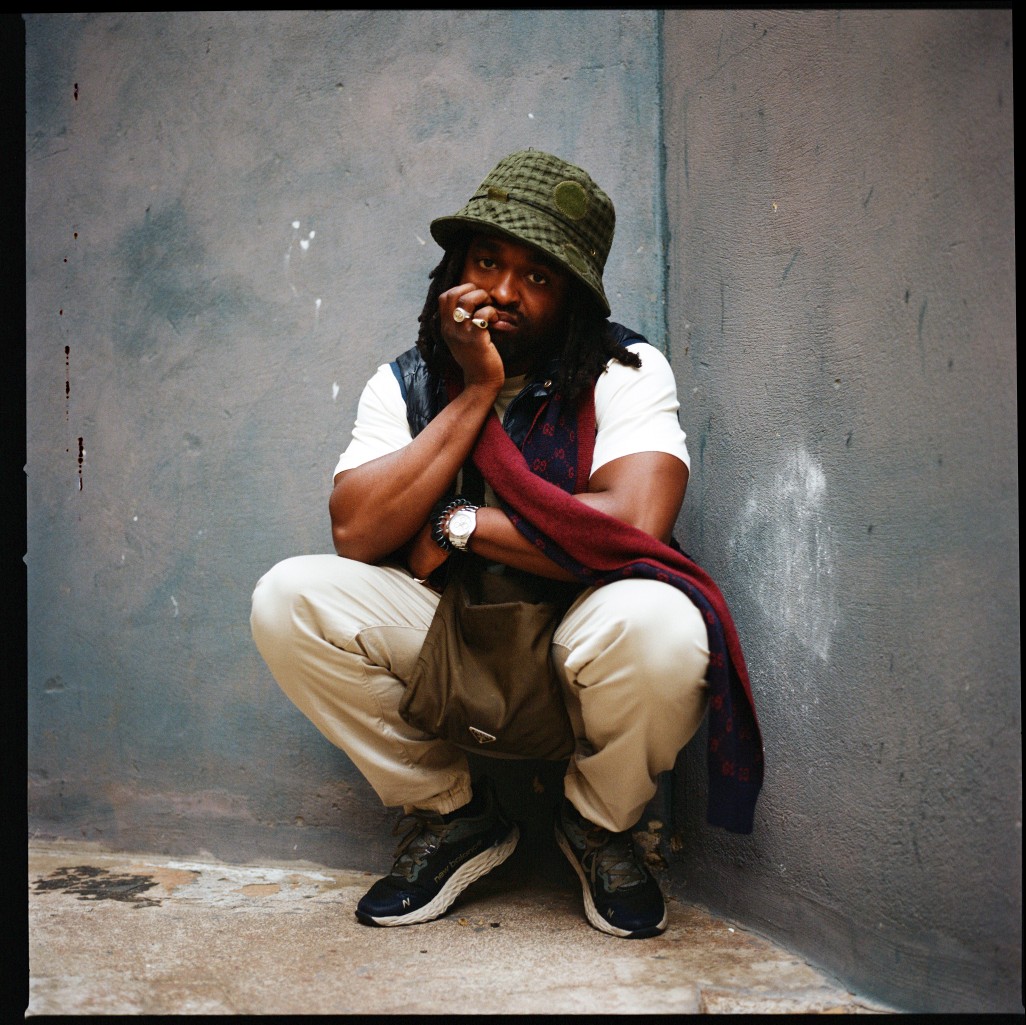

“I had to pay her back, he adds,” grinning, as though the prospect of a free guitar is hysterical; at which point, right-on-time Bill comes back up the stairs. Hak exclaims: “Bill, do me a favour, look for my scarf. It’s fucking expensive.”

Given the real-world challenges Hak faced in becoming who he is as an artist, it’s little wonder his songs are therefore based on daily observations, rather than alien, high-brow abstractions or aspirations. His music only discusses what he sees.

“I just like talking about my life. That’s it. That’s music for me: talking about my life and what I see… if I’m going to make music why would I jump back on whatever anyone else is doing? There’s enough fabricating and stuff–”

Bill walks in. He’s got the scarf. “Oh, thank fuck,” Hak says, giddily, before Bill says a few words about how expensive it is. “Oh, shut up,” Hak laughs again. “You know I’m not paying full whack for the gear,” he says, before dragging it back to the conversation. “Yeah, my music’s just about my life.”

That it is. His most extensive release to date, 2019’s Babylon, weaves a tale of his observations and societal circumstance, beginning with ‘Big House’, used “as an oxymoron, where I’m obviously talking about the man living in his big house, and also talking about the lads getting sent to jail.”

The EP continues, telling tales of being a ‘Lad’, loving women but having that special one (your ‘Mush’), and being absolutely ‘SKINT’ (“Not even a little bit, I’m talking flat on my face”).

Yet far from just being tough in the face of hard times, there’s a tender side to it, too. ‘Grief Eyes’, for instance, is an ode to Hak’s good friend, George; a sparky who one day went to work, “put his spanner on a bolt to unscrew it as he would normally,” Hak explains, “and some day they didn’t turn the electricity off, and it set him on fire.”

“Just seeing him trying to find some kind of normality in life or whatever the fuck he wants to call it, is just painful.” We hold a silent pause.

Perhaps from the slight tug of slight awkwardness, I try to change the mood and discuss other tracks. There’s some more upbeat moments in the EP, too, though… but Hak notices my attempt to steer the conversation to sunnier climes. “No, no, I’ve got no problem. I love – well, I don’t love – but pain, that’s where I’ve dwelled. That’s where I’ve put myself to grow up, really.”

“I’m 31 now and I feel I only really grew up last year. I only realised, ‘Oh, this is who you are. You don’t need to do this.’ I’ve finally grew up a bit and I think it’s wonderful for me. It just feels good.

“Everyone’s going through something. That’s the ultimate understanding: you’re not alone in this thing. That’s why I like to sing about it. And I guess it’s probably the main reasons why people come, because they feel at home whilst listening to music, or in a crowd – you don’t feel alone anymore. I used to feel alone in full rooms.”

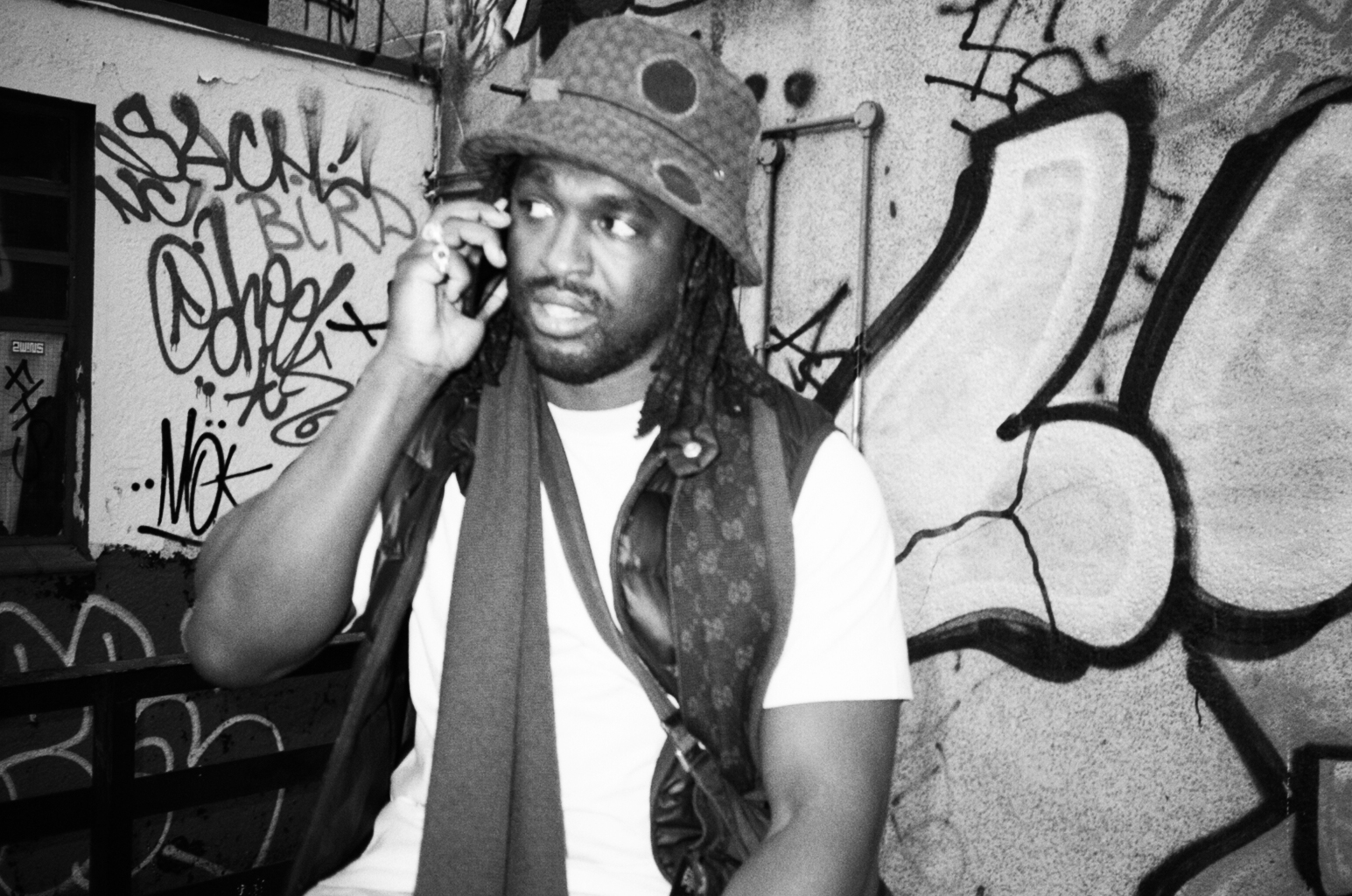

His performance later that evening can testify to that togetherness and the genuine feeling of connection Hak can manifest with his audience. At one point, he democratically asks the audience to cheer for the track they want; the euphoric ‘Thirsty Thursday’ narrowly beats the nostalgic ‘Venezuela Riddim’ and the anti-authoritarian ‘PC Plod’.

Equally egalitarian, support acts Mezzo and Rosie Holloway were decided simply after Hak posted on his Instagram, asking who’d like to play before him. Hak’s no stranger to supporting other artists. At the beginning of the year, his ‘Bricks in the Wall’ show at The Roundhouse in January was designed just for that, with support from lesser-known acts.

“I felt like I’ve always wanted to do that. I watched this documentary [Blitzed], about people clubbing in the 80s and they started going to the bars and pubs in Soho and made their own scene, basically.

“I felt I needed to do that for me and other leftfield black artists that are doing something but because they’re not fucking pop stars or rap stars, it’s difficult. So I thought, I’ve got this little platform, let’s do it.

“And we’re going to do more. It’s important just to show people that we don’t need the man; that we can do this through people power. I think that’s the most efficient power source on the planet.”

Such a spirit will no doubt endear Hak to Glastonbury, too, when he plays The Other Stage. You can picture it already, him shouting “who hates the police?” to a jubilant crowd; his lovable back-and-forth chat about being skint; and the triumphant trumpets that finish off ‘Thirsty Thursday’, beers flying in the air, just as they did at The Old Blue Last.

How are you feeling about it? I ask. “You’ve just got to take it in your stride. Half a bottle of tequila, we’ll be ready to roll,” he smiles.

Indeed, it obviously wasn’t to be for Liverpool that night, but wherever Hak is, you can be sure there’ll be a celebration. One derived from a joy for life, while equally conscious of life’s struggles. And just how precious this all is.