The harmonica might be one of the smallest instruments around, but it has a sizeable history, helping shape the sound of an entire genre and making its way into the palms of some of the most significant artists in history.

With edition two of ‘The Mick Jagger Series’ of custom-made harmonicas out now, in collaboration with whynow Music, we explore the journey of this humble instrument.

The harmonica originated about as naturally as you could imagine. Almost as naturally as harmony itself; only, it wasn’t called a harmonica, or a French harp or even a mouth organ, but took the form of a sheng, a free reed wind instrument made of bamboo that began life in China around 1100 B.C. Of course, the sheng, which usually consisted of around 17 bamboo pipes of varying lengths, was an instrument of its own accord, but it would pave the way for what we now know as the harmonica – even if it wasn’t the gift of music that was initially sought.

That’s because fast-forward to 1780 and the German-born physicist and engineer Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein was taking radical strides in the field of speech synthesis at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Building on the understanding of sound waves, Kratzenstein entered his “vowel organ” invention into a competition which aimed to explore the different tonal qualities of letters.

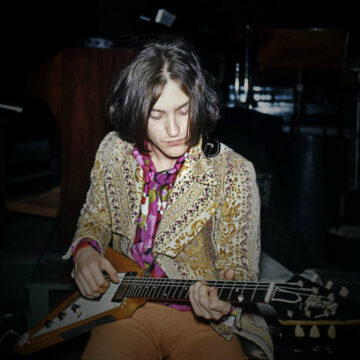

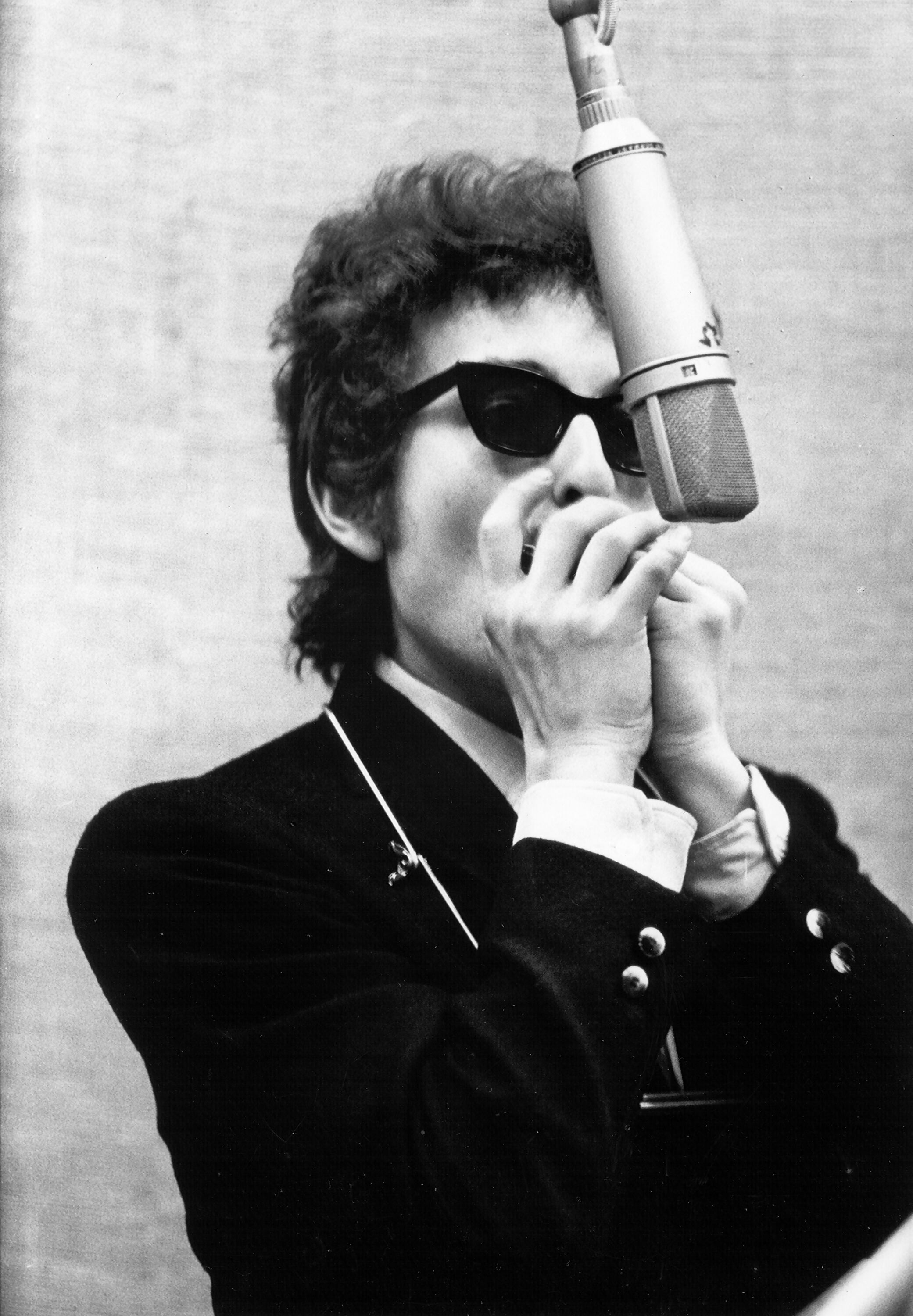

How did the harmonica makes its way into the palms of greats like Bob Dylan? Photo: Michael Ochs Archives.

No one knows exactly how or where Kratzenstein derived the idea for his first-placed entry (and a Christopher Nolan blockbuster to explain seems unlikely), but many have pointed to the sheng, devised all those years ago, as providing him with the obvious blueprint. Kratzenstein’s contraption, or “talking machine” as he called it, was initially about the same size as a piano, but over the next handful of decades more musically-minded inventors would condense this instrument down into a more pocket-sized form.

At this stage, the precise evolution of the harmonica is rather blurred, the waters rather muddy, but a few German inventors were finding new and novel ways to tweak the device. One inventor, Joseph Richter (not of Richter scale fame), developed the eponymous Richter-tuning, whilst a young instrument maker, Christian Bauschmann, would create what he called “The Aura”, which had fifteen reeds and mainly served as a pitch pipe.

This experimental little device would catch the attention of two clockmakers: Christian Messner and his cousin Christian Weiss, who churned them out as a side hobby and extra source of income. But as with many of the greatest inventions, it would take a savvy business mind to push the humble instrument far and wide.

Matthias Hohner wasn’t a particularly skilled harmonica player, but what he lacked in this department he made up for in market nouse. (Some evidence suggests he’d even trained with Messner and Weiss, whereupon he possibly saw, and even copied, the process of making the harmonica he would later popularise). By 1857 he’d established his namesake company, which developed some 650 harmonicas in its first year.

War has a habit of creating winners and losers, and during the American Civil War, Hohner was definitely a victor. By selling harmonicas to the US, largely through German immigrants who settled in its Southern belly, he would crack one of the fastest-growing markets, and create a foundation that would ensure his self-named business remains one of the foremost harmonica brands to this day.

Sales by this stage rocketed. Not only were many families buying them to give to their soldier sons and husbands on the frontline, providing some entertainment during rare moments of downtime, but at a time when much of America was on the move, there would be few more portable, music-making devices. By the turn of the century, Hohner was producing over four million harmonicas each year, employing more than 1,000 workers to keep up with demand.

The likes of Little Walter would eventually change the game for the trusty harmonica. Photo: David Redfern.

Much like we might look back today and gawp at earlier iterations of the iPhone, so too was the harmonica seeing gradual and effective improvements during this period. In 1896, Hohner released the classic Marine Band harmonica – an affordable, lightweight, mass-produced variation (the Ford T Model of harmonicas, if you will).

By 1910, the sophisticated Chromatic Harmonica was developed, which had a button on the side; when pressed, it would redirect air to a selected reed plate, thereby making all 12 notes in the standard Western chromatic scale available. Suddenly, there was a hand-sized instrument of true power, capable of expressing the full emotive range of its player.

What came next was creative ingenuity of a different kind. With its plangent wailing and vibrato texture, the harmonica lent itself naturally to the blues. It would provide a very young, Tennessee-born DeFord Bailey with one of the few means of escapism after he contracted polio aged just three-years-old.

The grandson of slaves, Bailey would go on to be a competent multi-instrumentalist, but his real love was for the harmonica – so much so he would later gain the nickname the “harmonica wizard” and would be one of the first performers on the prestigious Grand Ole Opry radio broadcast, where he’d play the instrument.

Few did as much to add to the deep-rooted associations between the harmonica and the blues than Sonny Boy Williamson. Photo: Michael Ochs Archives.

Whilst Bailey was a key figure in broadcasting the warbling sounds of the harmonica further to the masses, few did quite as much to add to its appeal and deep-rooted associations with the blues than Sonny Boy Williamson.

One of the most recorded blues musicians of the ‘30s and ‘40s, he not only set a tone and timbre for the blues but demonstrated the versatility of the harmonica, applying it through the likes of uptempo blues standard tune ‘Good Morning School Girl’ and the achy ‘Sugar Mama Blues’ – the latter demonstrating just how the instrument could get across a depth of feeling, well, the blues.

Sonny Boy Williamson’s style would make him the blues artist’s blues artist. His sound would inspire the likes of the rather sublime Marion Jacobs – the Louisiana-born harmonica virtuoso better known as Little Walter, who perfected the tongue-blocking playing technique that produced an exceptionally smooth sound, and whose track ‘Juke’ is seen as the unofficial anthem of blues harmonica.

Non-harmonica-playing artists such as the father of the Chicago blues himself, Muddy Waters, would also be heavily influenced by the sound of Sonny Boy Williamson.

Photo: David Redfern

Whilst Little Walter and Muddy helped define the blues in their own right, music is an ever-cascading trickle of influence, one generation of artists encouraging the next. The fact a young, skilled harmonicist Aleck Miller would later change his name to Sonny Boy Williamson II, in an attempt to reap some of the benefits from the success of his namesake, says a lot about where the artist’s inspiration in relation to the instrument derived.

The success and, more importantly, the sound emanating from many of these African-American blues musicians likewise permeated the nascent rock n’ roll scene. Much has been written of the potent mix of jazz, blues and country music which converged to form this truly seismic episode in music and life more broadly, but the symbol of the harmonica remains a connection between the old and the new; between a time of great new change and a tradition harking back to an old America that shaped it.

A few moments and figures would capture this in particular. In March 1963, a young folk singer was invited onto WBC-TV to play tunes from his forthcoming album, one that would truly begin to assert the singer-songwriter as one of the defining artists of the 20th century: The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.

Playing one of his most enduring compositions, ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’, Bob Dylan wasn’t just armed with his trusty guitar, but a neck rack and harmonica that helped mould his image as a road-travelling troubadour with music pouring from every available limb.

Around this period, too, American kids would be tuning-into their favourite music programme, Shindig!. The MTV or SB.TV of its day, it supplied them with their fix of rock n’ roll. On one particular evening in May 1965, England’s lively new group The Rolling Stones would be making an appearance – but only having forced an agreement with the show’s producers that the unsung blues artist Howlin’ Wolf, who they so admired, also played.

Despite a then- 54-years-old Holwin’ Wolf having previously recorded at Memphis’ Sun Records before moving to well-regarded blues label Chess Records, he had often been overlooked.

This performance, in which he played the trusty ol’ harmonica with aplomb, the camera honed-in on his solid face, put him momentarily back in the spotlight. What’s more, it represented a handing-over of the baton, harking back to a former age of the blues whilst nodding to the future, as Mick Jagger – who’d go on to wield the harmonica more and more throughout his own iconic career – and the rest of The Rolling Stones watched on.

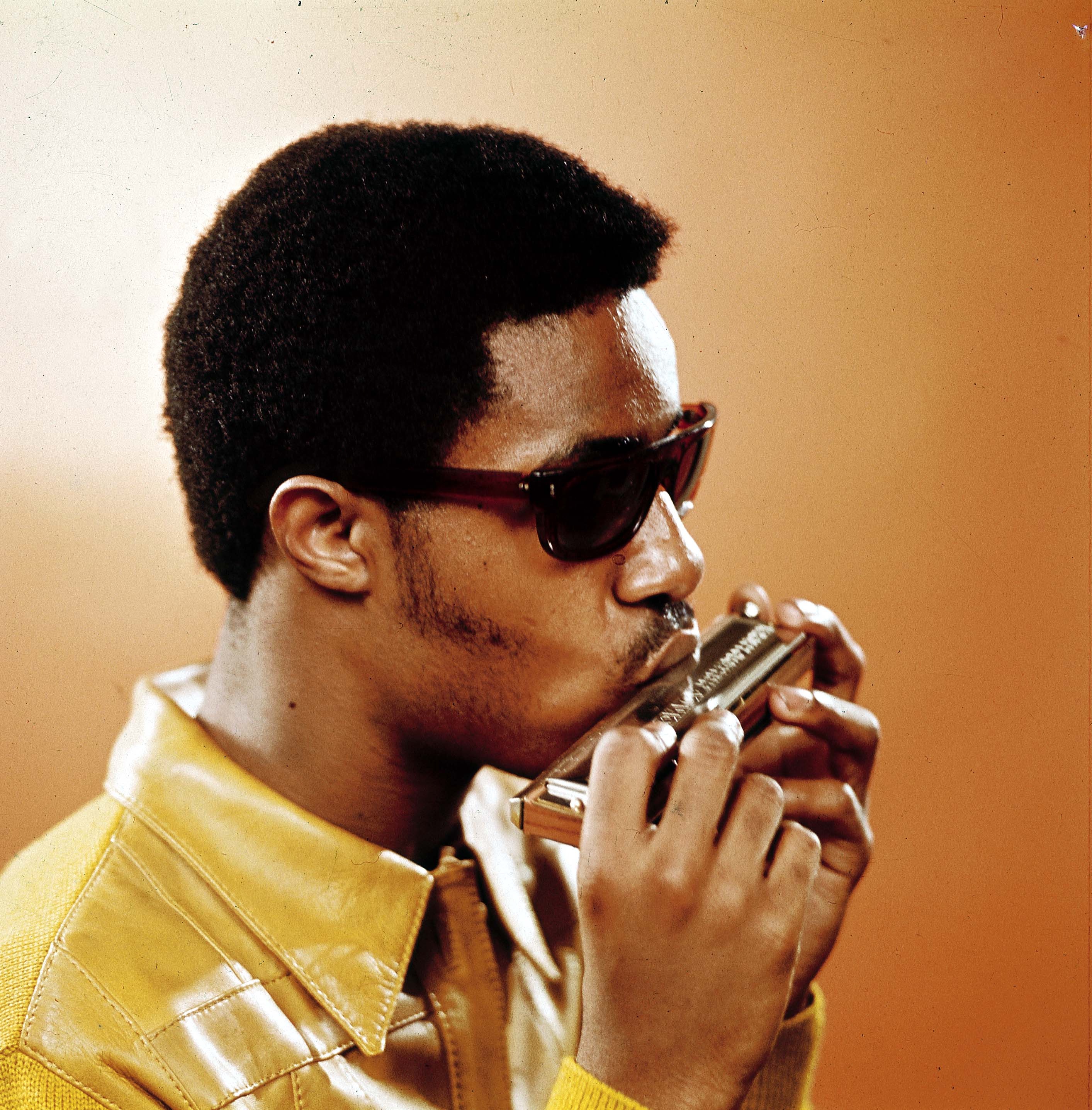

By November 1968, too, an easy listening instrumental rhythm and blues album Eivets Rednow was released, which put the harmonica largely front-and-centre. It was the work, of course – if you spell Eivets Rednow backwards – of Stevie Wonder. Whilst this extraordinarily gifted performer may best be imagined at the side of a piano, he was in fact better known as a youngster for his ability to bend notes on a harmonica.

Stevie Wonder playing the harmonica. Photo: Redferns.

Throughout Wonder’s storied life in music he hasn’t just applied his dab-hand on the instrument to his own work, but added harmonica solos to the likes of Chaka Khan’s 1979 chart-topping single ‘I Feel For You’ (originally written by Prince), as well as Elton John’s soft rock classic ‘I Guess That’s Why They Call It the Blues’ – an aptly-titled track given it referenced the genre of Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter and Muddy Waters.

And so this nifty instrument, which has seen many variations over the decades and even centuries, figures in the 20th century as an emblem through which genres, sounds and styles merged and evolved. Beneath its history lies a story of great ingenuity, enormous skill and timeless tunes. It may be one of the smallest instruments around, but this pocket-sized instrument packs a punch.

And now you can get your hands on edition two of ‘The Mick Jagger Series’ of custom-made harmonicas, which are sold through whynow Music.