Having trouble finding love? We spoke to two experts in the field to find out how romance is faring in the world of dating apps.

My granddad passed away last year. I think about him quite a lot. A genial man, yet by no means a pushover, Owen Coward had a knowingness about him that at times felt like it derived from an age gone by. It presented itself in a calm, collected repose that could get what it wanted without force. He hardly ever raised his voice. He wouldn’t need to. And in the very rare times he did (as when he took me aside, aged 6, for giving my mum grief about football training), you understood there was some cosmic significance to his command.

One thing that’s always eluded, even baffled, me at times, however, is the longevity of his relationship. At his and my grandma’s 60-year wedding anniversary (their ‘diamond anniversary’, which certainly sounds as precious as a rare stone in today’s age), he revelled in the story of meeting his life partner, Brenda.

“And then I saw her at the school dance,” he grinned, “and I thought, ‘what a cracker, she’s the one.’” There was a majesty to his simplicity. They met when they were 15. At 20, they were married; at 21, they had their first child: my uncle, Tom. By the time they were my age (22), they had two kids; by my brother’s age (25), they had three kids and had bought their own house.

Such a tale seems a world away from our current debt-ridden, student-loan-saddled, Tinder-swiping, Love Island-watching, Tik-Tok-making generation. No doubt we all have the capacity to think we live in the worst of times, when in all likelihood we don’t. My grandparents, for example, were born the year the Second World War broke out – certainly not the best of times. The difference, however, in the way we conduct our relationships seems stark.

It isn’t anecdotal either. The proof is in the statistics. According to the Office for National Statistics, in 1950 there were 30,870 divorces and 358,490 marriages. In 1972, aided by the Divorce Reform Act, which enabled couples to separate after being apart for two years, divorces jumped to 119,025.

More recently, in 2019 there were 107,599 divorces, which was up by a whopping 18.4% from 90,871 in 2018; although some say the scale of this increase partly reflects divorce centres processing a backlog of casework in 2018, which is likely to have led to a higher number of completed divorces the following year.

Though we’ve never uncoupled faster than we’ve coupled, the trend is clear: divorce rates have gone up; marriages have gone down. And whilst, of course, marriages are by no means synonymous with love, the growing divorce rates do point towards an evident breakdown in long-term romantic relationships.

So, what’s occurred? Why have our long-term relationships diminished so much? What impact have dating apps like Tinder, Bumble and Hinge had on our modern-day romances? Would my granddad have stayed with my grandma if he’d had the ability to swipe right or left on an app that provided him with a seemingly infinite number of women?

Professor Viren Swami of Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), a social psychologist and author of Attraction Explained, told whynow that much of our modern approach to dating operates “in a kind of rejection mindset”, in which “when you’re offered more things, you tend to reject more often than you would with fewer options.”

“If you go into a shop and see 10 pairs of jeans, all different styles, the assumption is you’d have a better choice and would therefore be more likely to make a purchase. But what happens is that because you have too much choice, you’re actually much less likely to buy something.

“We also know,c he adds, emphasising the comparison of dating to such commodified means as shopping, “that when you enter a rejection mindset, you also evaluate people on the wrong sorts of criteria. Some psychologists have talked about this in terms of “relationshopping”, in which we end up treating other people essentially as objects.

“We look at them as criteria and ask: “What do they have that they’re willing to sell to me?” And we dehumanise people.”

Indeed, a study in 2010 by US academics suggested that the concept of shopping was “highly salient” to people using dating apps, as it was a system they were already familiar with, one that deals with “the presentation and selection of goods”; an idea supported by Professor Adam Arvidsson, who describes users on dating apps as engaging in a branding process of presenting their profiles to others, which he terms “the commodification of affect”.

“In other words,” the study added, “they shop.”

It’s an aspect to modern matchmaking that’s recognised by dating and relationships consultant Dr Kathrine Bejanyan, who views dating apps especially as “orienting us towards surface-level- character characteristics; the short-term stuff.”

“I think couples or individuals who dated before dating apps approached things very differently from those who used modern styles of dating. The things we look for when we’re dating now tend to be different from what makes a long-term relationship successful.

“For long-term success you must have characteristics, values, integrity, openness, communication, honesty, conflict resolution – all the stuff that’s on a much deeper level.

“Whereas when you’re dating, particularly on dating apps, we want common interests, we want to know how much fun we can have with someone, how attractive they are. It’s the stuff on paper, the superficial characteristics, that makes someone attractive to us, and we’ll often look for that.”

Yet dating apps aren’t the blame-all ailment for modern-day romantic woes. Just like much of our lives on the interweb, our sense of self has proliferated. We are both here and nowhere, able to speak to and meet with anyone, at virtually any point in time, from practically any part of the world.

Amongst all that, what dating apps can do, Professor Swami says, is “bring people together who are, in a very vague and abstract sense, generally suited to one another; people who might have the same values in life, who might have the same hobbies and desires. They’re very useful at bringing the right kind of people to the same space. They’re just not so good at getting people to end up in healthy relationships.”

Again, Dr Kathrine concurs. “Especially during the COVID age, a lot of us wouldn’t have been able to date if it wasn’t for dating apps. So they’ve actually been something of a godsend. But people get caught up with the way the dating apps are formulated, rather than using them effectively.

“If you’re not intentional about the way you are approaching dating apps and how you meet people, you’ll end up being used by the apps rather than using them effectively. Apps in themselves aren’t good or bad. They’re a tool. And, like a knife, if used incorrectly we could cut ourselves. But a knife isn’t good or bad. It’s just a tool that gets a job done.

“Something I often say to clients is don’t match endlessly. Try to be as purposeful and reality-based with dating apps as possible, with no more than 10 matches at a time. And put the intention on talking to people.

“If you’re swiping more than you’re engaging one-on-one, then you’re using it the wrong way; it becomes more of a gambling machine, rather than being used for what it’s for.”

Furthermore, it can sometimes be all-too-easy to deride a new technology as the sole reason for societal ills, not least with a subject matter like love and relationships, which Professor Swami regards as “incredibly complex, as people’s psychology is incredibly complex, and we’re not just talking about one person, but two people in a relationship or a fledgling one.”

Another key issue, he explains, is economic factors. “If people don’t have the stability of economics, they aren’t able to form healthy relationships.

“What do people do when they enter a relationship? They ultimately want to build a family. To build a family, you need money, you need a home, work, and long-term economic stability. When you don’t have those things, it increases stress, and when you increase stress, you take it out on your partner because they’re the closest to you.

“When you have those things, though, it makes it much easier to form and maintain healthy relationships. The reason why in the ‘60s we had lots of long-term, stable relationships, was partly cultural – people didn’t think it was acceptable to divorce or leave their partner – and it was partly a time of much greater economic freedom. They were economically stable and that meant they had families and homes they could build that were viable.”

This point inevitably brings to mind my grandad again, who, with a stable job for a pharmaceutical company, was able to settle down with his then-wife at an age many people of my generation would likely gawp at.

What further complicates things, Dr Kathrine adds – touching on a growing divergence between generations – is the younger generation’s desire “to be in-tune to a more emotional connection.”

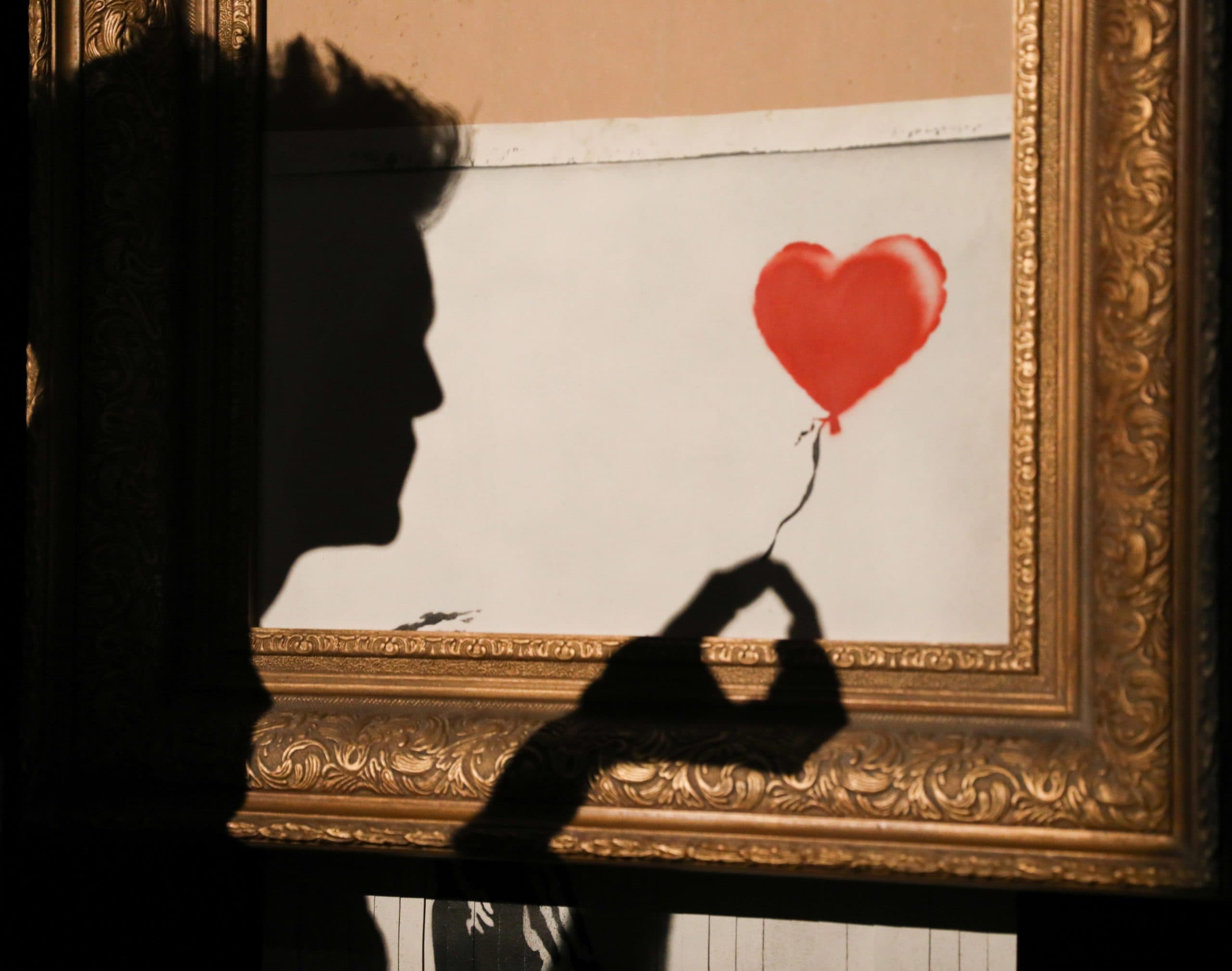

How we looked like before dating apps… probably.

“For older generations – our parents’ and grandparents’ generations – relationships were about creating a family home together. A lot of the younger generation now might not even want to have kids or invest in buying a home – they can do a lot of those things on their own. What they’re really looking for is more of an emotional connection at a level that wasn’t a thing for previous generations.

“They want to feel more emotionally in-tune; even if the relationship is functional, it’s not enough for younger generations, they want more. It’s a bit like work: previous generations were happy if they got a good salary and a good pension. Now, people think, “I want to do something that’s meaningful, I want to contribute, I want to do something that makes me come alive on an emotional level” it’s not just about getting a good pay cheque.”

Are we the victims, then, of our own ‘success’? If, that is, success is a greater understanding of one’s emotions or desire for greater fulfilment. Perhaps. Yet should we also temper this with a realism which admits that not everyone or any relationship is perfect? Probably so. Does this article profess to know all the answers? Certainly not – at which point you may choose to swipe left.

One thing is clear. Whether you deem it as simply dutiful stoicism or lifelong romance, we can thank our grandparents’ desire to be with someone, even if only briefly. Without that, we wouldn’t be here.

We reached out to Tinder, Bumble and Hinge for comment. None of them commented.

Viren Swami is a Professor of Social Psychology at Anglia Ruskin University ARU. He is a Chartered Psychologist and Associate Fellow of the British Psychological Society and is ranked in the top 2% of the most-cited scientists in the world.

Dr. Kathrine Bejanyan holds a PhD in social psychology, concentrating on romantic relationships, and Master’s in counselling psychology. She is an accredited member of the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy and has worked for companies as a resident relationships expert. For more information on her work, click here.