What’s in a name? More than you might think, because it turns out a lot of them are, well, a little on the wobbly side. The misnaming of things is a fascinating category within language because the results frequently shed light on beliefs and understandings of their time. Why should an ostrich not be called a ‘sparrow camel’ when the ancient Greeks had very little to go on? And if the original Aztec name for the avocado, ahuacatl, made more sense to us as ‘alligator pear’, then who are we to argue? Below are my top ten picks of names that have never quite hit the spot.

Jerusalem artichoke

The Jerusalem artichoke has nothing to do with the Holy City and everything to do with the fact that English speakers struggled with the Italian girasole, ‘sunflower’. And, just to add to the confusion, it’s not really an artichoke either.

seagull

Strictly speaking, a seagull is really just. Despite the fact that ‘seagull’ has been recorded since the 1500s, this is a hill that many dedicated birders choose to die on.

READ MORE: Susie Dent’s Introduction To Swearing: A C-Word, But Not That One

umbrella

At the heart of the word ‘umbrella’ is the Latin umbra, meaning ‘shade’. The originals were intended to shield people from the intense heat of the sun. So when an Englishman by the name of John Hanway began carrying an umbrella down the rainy streets of London, he was hooted at, jeered, and publicly lampooned.

jellyfish

Neither a fish, nor made of jelly: rather, this is the popular name of various acalephs, medusas, or sea-nettles. They are of course gelatinous, so we can’t blame anyone for thinking of the wobbly stuff when naming them.

peanut

Nor is this a nut in botanical terms. It is a legume.

quantum leap

English is an eccentric language. Why talk about a ‘meteoric rise’ when meteors fall? Or a dramatic advance as a ‘quantum leap’ when in physics this is not a major change at all, but a tiny jump in terms of size. But a quantum leap is admittedly pretty dramatic, and so the phrase has been harnessed to describe a sudden and extremely large increase.

pineapple

The original pine apple was the fruit of the pine tree, i.e. a pine cone. When the pineapple fruit was introduced in the early 17th century, its shape and segmented skin were clearly imagined as a giant pine-cone, and so the name was simply transferred over. Simples.

grapefruit

Well, it is a fruit, but clearly has nothing to do with grapes. Its name probably reflects the fact that grapefruits grow in clusters.

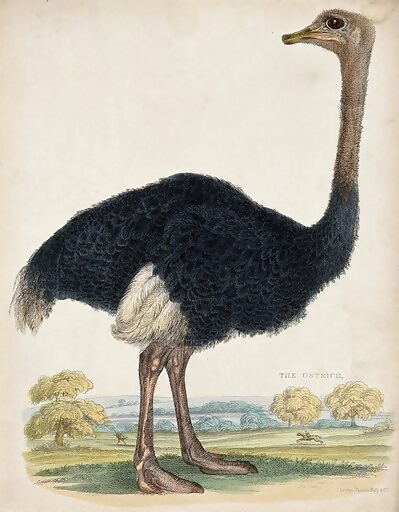

sparrow camel

It’s hard to believe, but when the ancient Greeks first observed the long-necked bird we know today as an ostrich, it struck them that it looked a little like a cross between a sparrow and a camel. Consequently, they knew it for a while as a strouthokamelos, 'sparrow camel’. Not only that, but a giraffe was a ‘camelopard’. They clearly liked their hump-backed even-toed ungulates.

Spanish flu

The 1918 pandemic of influenza is thought to have originated in the US, but relatively early on in its course it became particularly severe in Spain. Our Spanish neighbours have taken the rap ever since.

2 Comments

I have admired Susie Dent and her skills in lexicography for many years.

She is undoubtedly the best! 💖

I understood it wasn’t so much that outbreaks were severe in Spain as that wartime censorship didn’t apply there, so cases of the flu were reported there and not in other countries.