Have you ever had a job at a call centre or somewhere equally soul-destroying where they don’t even let you keep your name? There’s already someone on the team with your name and for reasons of corporate nonsense you can’t keep it. You must adopt a different identity for the convenience of someone else.

Now imagine that you are a national hero, internationally celebrated. People scream your name like you’re The Beatles at Shea Stadium, but you’ve never once been able to reveal your real identity. What’s in a name?

British Olympic hero Mo Farah can tell you.

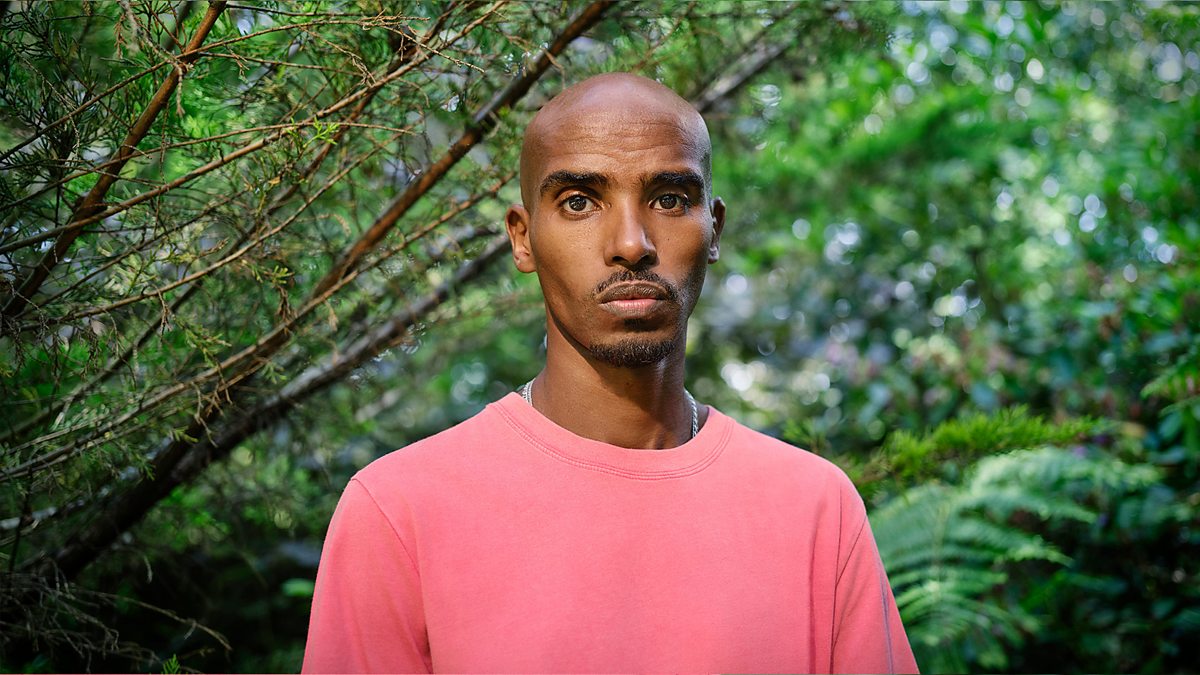

British Olympian Mo Farah has revealed his extraordinary origin story in a new BBC documentary

The extraordinary story told in the BBC’s The Real Mo Farah contains shocking and deeply unpleasant revelations about his background and how he came from Somaliland to the UK as a child. His ability to keep his story private and tell it in his own time is astonishing too, as the subject of intense media scrutiny since the 2012 Olympics.

Bravely and eloquently, he challenges our very fuzzy perceptions of what people trafficking looks like. As a small boy he’d already lived through civil war and the death of his father before he’d lost all his baby teeth. He and his twin brother were sent to Djbouti as a refuge from war, but they were separated and at the age of nine he was trafficked to London by a family he didn’t know under the stolen identity of Mohamed Farah. His real name was Hussein Abdi Kahin. There he was forced into domestic servitude. He was separated from his family, not knowing even if his mother was still alive.

Aged 11, he was finally allowed to go to school where he had a very difficult time. A report says he was “emotionally and culturally isolated” and a teacher wrote “I feel sad when I’m with him.”

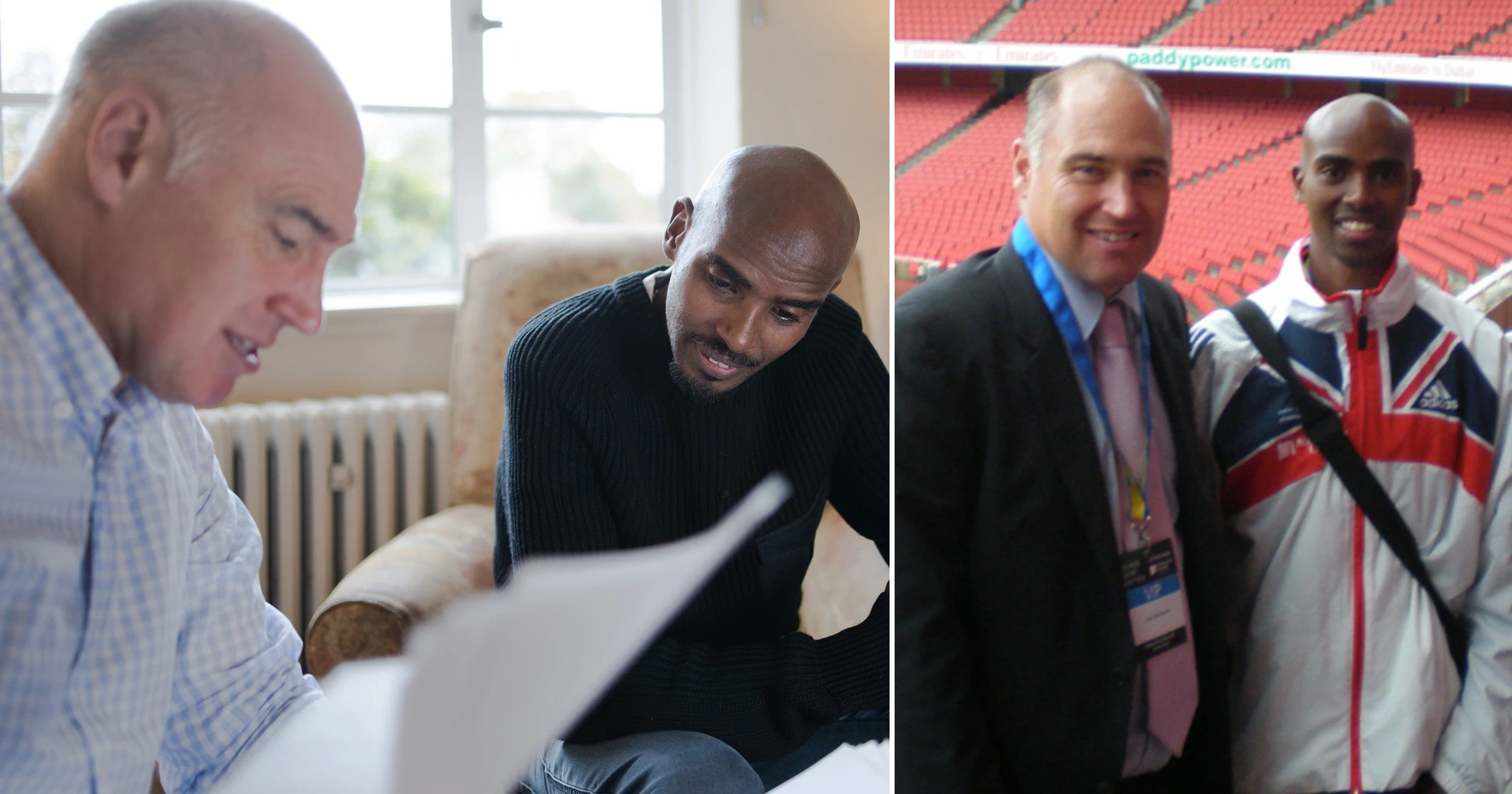

Sport was his escape; no language barrier and no difficult questions to answer. He was literally running away from it all. His PE teacher, Alan Watkinson, spotted Mo’s potential and moved mountains for him to compete internationally by applying for his British citizenship. Would those efforts have been made for a less exceptional child? His citizenship was technically obtained by fraud, but never reported to the Home Office. Coming forward, even now, makes Mo nervous for his status and that of his wife Tania and their children.

Sir Farah’s PE teacher Alan Watkinson spotted Mo’s sporting potential immediately

While still a child Mo had to find the courage to rescue himself. He was taken in by his Somalian friend’s mum Kinsi, finding a place of sanctuary there despite Kinsi being closely related to his traffickers. This is a jarring moment in a rags-to-riches story but underlines the complexity of his personal situation. He opened up eventually to his wife Tania, on the eve of their wedding. She says, “I’d worn him down”.

The documentary telling this story – available now on BBC iPlayer – is so engaging because Mo himself is famously engaging. He’s an enormously empathetic character, already well-loved by the public. Up until now we also thought we knew him well too. He’s very aware of his talent and the privilege that that’s afforded him; a fresh chapter after a terrible start in life. This would have made a heck of an episode of Who Do You Think You Are.

As he returns to Africa, taking his son to visit his family, he’s thinking about all the life he gained and all the life he lost. His feelings of gratitude are complicated, written all over his face as he asks difficult questions of his mother Aisha and brothers in Somaliland. Ultimately someone from his own family may have been responsible for trafficking him. He doesn’t want to consider this, but it clearly plays on his mind frequently.

To those with no empathy for immigrants or refugees, whose knee-jerk reaction is “strip him of his medals and send him back!”: he was a child. He was nine.

Mo Farah’s story raises questions about the nature of people trafficking in the UK today

Anger should be directed to those who deserve it, and we must task our politicians with working out how it was ever allowed to happen. Where on earth were social services in all this? And how many children today are in similar positions, hidden in plain sight?

The truth is we know so little about people trafficking, and the real human cost to the victims. It’s a sanitised or a sensationalised subject, if it’s mentioned at all. We turn our faces away thinking it’s not something that happens here in the UK. When of course it does.

Mo’s feelings of guilt and shame have been internalised over 30 years, like so many survivors of abuse in all its forms. Lying is a sin, says his mum and he’s been forced to sin, but not at his bidding. Government policy is painting the criminals and the victims as being basically one and the same. Who cares enough to distinguish between them and deal in the nuances and grey areas? In Mo Farah’s case the Home Office have said they will take no action.

What about all the others in his situation? This is a personal story of immense fortitude and perseverance. Mo has made the UK so proud, but immigrants, however they arrive, shouldn’t have to be exceptional to be made welcome.

At broadcast the reaction on social media was largely positive, with tweets calling it “astonishing” and “heart-breaking”. There was praise heaped upon Alan Watkinson and the impact of teachers on young lives more generally; “With the right teachers you can conquer the world”. There was also concern about the failure of social services and border agencies. Has anything changed for the better since Mo arrived? It’s an uncomfortable thought that we should not shy away from.

Unpleasant comments were thankfully small in number. The nastier ones included people suggesting the story was “fake”; “He’s Somali, a species with unfair advantages in long distance running. He is an illegal immigrant and no hero of British athletics.”

Ben Myatt has my favourite tweet of the night “If your first reaction to his story is “He’s illegal and should be deported” I suggest you start walking into the Atlantic Ocean. We’ll tell you when to stop.”

The Real Mo Farah is an affecting portrait of a cheerful and optimistic sporting hero, nudging into national treasure status, stirring up emotions and rightly so. Mo’s star power shines a light onto dark subjects that need much more awareness and understanding. A high-profile BBC documentary is a good place to start that conversation.