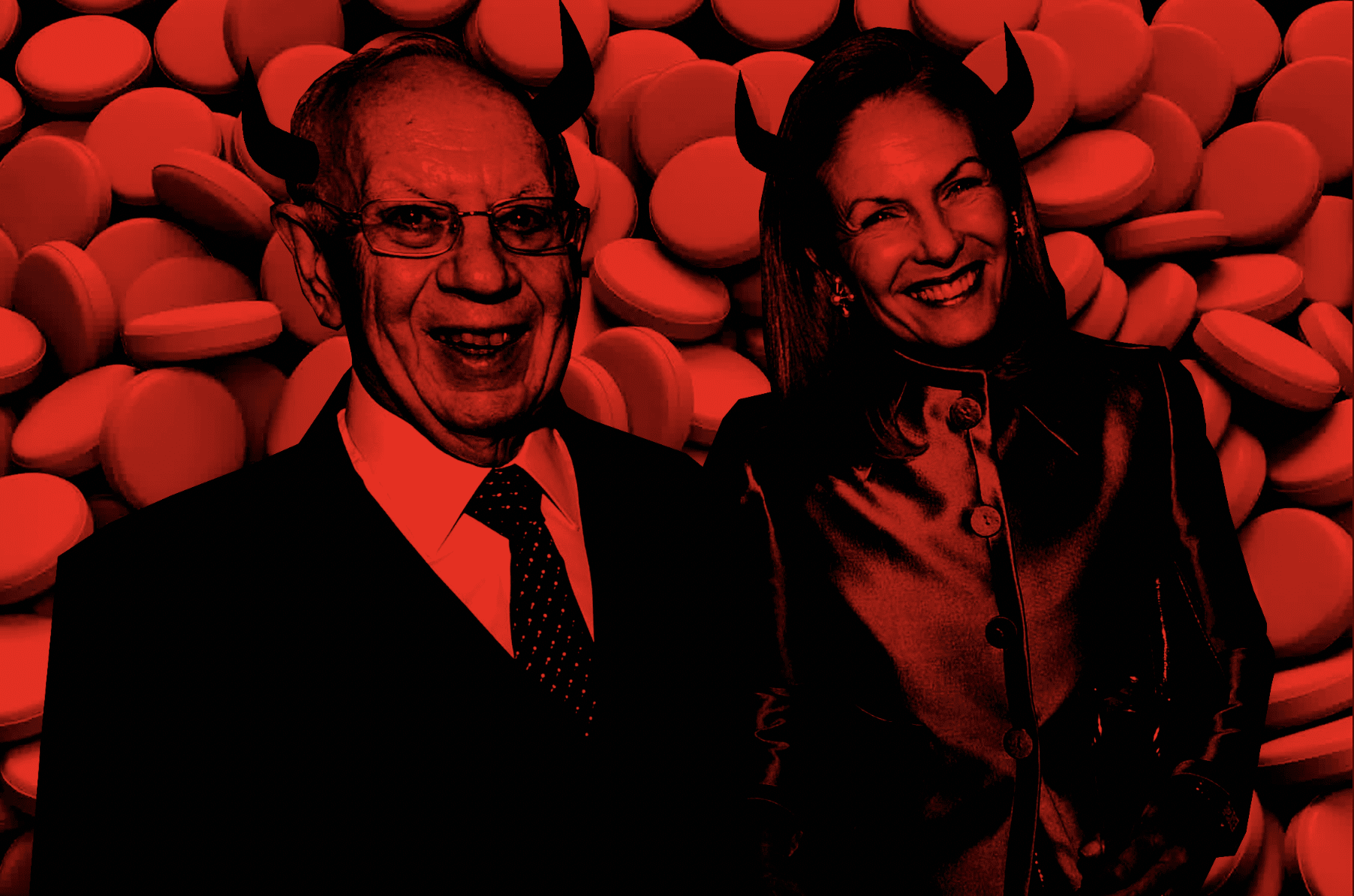

Forget charity and goodwill, it is the pursuit of immortality that drives the Sackler family’s donations, as their blemished wealth continues to whisper in the ears of Britain’s cultural institutions.

In 2019, having contributed north of £60m to British institutions over the course of the last decade, the Sackler Trust announced it was suspending donations. Embroiled in mounting controversy over the family’s role in America’s opioid crisis, the London-based trust described ongoing donations as a “distraction.” But just a year later – having made no further comment on resuming their ‘philanthropy’ – the Sackler Trust committed over £14.5 million to institutions across Britain, accounts filed last December reveal. Over £8.6m of that £14.5m remains payable beyond 2021, and the accounts lay out £39.9m in future investments, for “the medium to long term.”

In the same year that the Sackler Trust silently resumed donations, 2,263 people died from opiate related drug poisonings in the United Kingdom. This represents a 48 per cent increase from 2010, while opiate-related hospital admissions rose at the same rate between 2008 and 2018, costing £137 million in treatment. On the decade, opioid overdoses have increased by 87 per cent, to 12,000 annually.

These numbers pale in comparison to America’s epidemic – which has now claimed more than half a million lives – but make no mistake: Britain, too, is in the midst of an opioid crisis. And though the high profile institutions renouncing the Sackler name will make the headlines, their drug money still flows, and still influences British culture. Money talks; wealth whispers.

The Sackler Trust is bankrolled by the family who owns Purdue Pharma – the American pharmaceutical giant that made its fortune off the highly addictive painkiller, Oxycontin. Oxycontin is the 35 billion dollar brand name that Purdue Pharma gave to the drug Oxycodone, when they launched it in 1995. Initially, Oxycontin was released with FDA-approval, claiming the drug was safer than rival painkillers, because the Purdue-patented, slow-release form of the drug, Oxycodone, was supposedly less liable to abuse. The examiner who oversaw this approval, Dr. Curtis Wright, had a job at Purdue Pharma two years later.

Sackler knowledge of, and thereby culpability in, Oxycontin’s role in America’s opioid crisis is now widely acknowledged. They knew the dangers. They hid them. They sold buckets and buckets and buckets of Oxycontin instead. That is no longer a breaking story. Patrick Radden Keefe’s 2021 book, Empire of Pain – following his 2017 expose in The New Yorker – tells it best, and prompted the renewed calls for institutions to distance themselves from the Sacklers. Tate removed the Sackler name from their various walls two weeks ago, while the Serpentine Galleries did so last month. New York’s Metropolitan Museum – which was home to the vast Sackler Wing featuring some of the museum’s most prized possessions – dropped the name last December, while the Louvre in Paris led the way, cutting ties in 2019. Unsurprisingly, none of the galleries commented on the family’s role in the opioid epidemic when doing so.

These institutions are just some of the big names involved with the Sacklers; even the Sackler Trust itself is just one of three Sackler-funded charities in the UK – the other two being the Dr Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation, and the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Foundation. Combined, the three have donated a total of £168.5 million since 2009. Eye-watering, knee-weakening cash, and yet it is the breadth of Sackler dealings in this country that is truly most staggering. Their money is everywhere. Everywhere. From the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Old Vic, to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, to Kew Gardens and the Royal Opera House, to Chelsea Westminster and Moorfields Eye hospitals – you name it, chances are they’ve taken money from the Sacklers. The slimy tentacles of the opioid-funded family stretch throughout British society, buying influence in some of the most respected, historical and important institutions in Britain.

For the Sackler’s philanthropy isn’t really about generosity. The extent of their donations proves there is no concerted, driving moral goodness behind them; nobody supports everyone and everything. Rather, the Sacklers want their name pasted on the walls of as many of the world’s most important institutions as they can find, and they want them there for eternity. The trust is merely an exercise in self-promotion, in ‘reputation laundering’, in whitewashing sins; ultimately, in living forever.

Depending on what corner of the internet you believe, it was either Banksy or the Egyptians who said you die twice: first when you draw your final breath, and then again when your name is said for the last time. Whoever uttered that wisdom – almost certainly not Banksy – it is the second type of mortality that the Sacklers are hoping to evade. After all, the three brothers – Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond – who took the Sackler name from the streets of Brooklyn to the walls of the finest institutions in the world, are all already dead. Yet here we are, writing about them, reading about them, talking about them.

Philanthropy throws a cloak of invincibility over people. How could you possibly attack someone donating such gargantuan sums of money to charitable causes? Well, exactly, and the Sacklers are not the first to employ this tactic.

In 1909, G.K Chesterton wrote an article for The Illustrated London News. It began: “Philanthropy, as far as I can see, is rapidly becoming the recognisable mark of a wicked man. We have often sneered at the superstition and cowardice of the mediaeval barons who thought that giving lands to the Church would wipe out the memory of their raids or robberies; but modern capitalists seem to have exactly the same notion; with this not unimportant addition, that in the case of the capitalists the memory of the robberies is really wiped out.” This passage, omitting the first line, serves as the epigraph for Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain.

Giving to the Church in the medieval ages washed the sinner’s hands of their blood. It also provided – I suppose more directly, if only in the belief of the barons – a path to immortality. Human nature hasn’t changed. We want to be loved and we want to live forever. What more could you ask for?