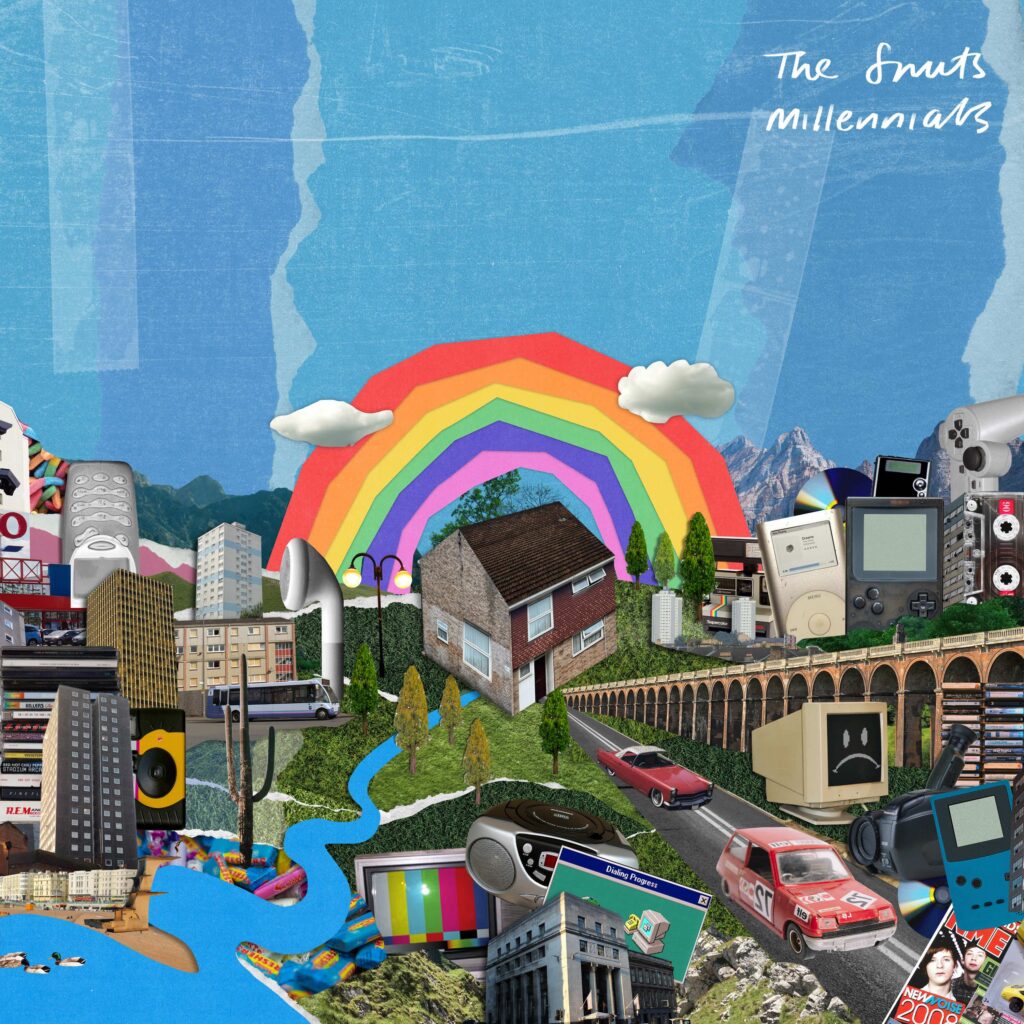

The Snuts’ third studio album, Millennials, is out now via the Scottish indie-rock outfit’s own label, the poignantly titled Happy Artist Records. Whilst the band’s 2021 debut W.L. and 2022 follow-up Burn The Empire bagged them a UK Number 1 and Number 3 album chart accolade, respectively, the confines of the personality-obsessed music industry was quietly taking its toll.

What you have in this band is four best mates: frontman Jack Cochrane, guitarist Joe McGillveray, bassist Callum Wilson and drummer Jordan Mackay. This winning formula is at the core of their drive to make music and has helped spur them in creating a devoted fanbase. It’s also, in part, why they felt it necessary to break away from their major label Parlophone and the music industry at large, with its growing obsession for reality stars and social media clout.

Millennials is a testament to their newfound creative freedom, with its gloriously catchy, festival-ready bangers and lyrics that embrace how their lives were before the more controlling aspects of the music industry took hold. We speak to Jack Cochrane to find out just what this record encapsulates.

Jack, how does it feel putting this album – your third record, Millennials – into the world?

It’s cool, man. The two records we made before were both in COVID times, so this one is so different. For the first two there was a disconnect making music and not actually getting to feel that fucking energy. It’s nice getting down to gigs and actually shitting yourself playing new songs to people, wondering if they’ll like them.

The first two records also had so much worry and pressure. There was a feeling I think that someone could just take this away from you at any stage; that our output could not be good enough. I feel like with this record, in splitting with the label, it was on us – if things didn’t go the way we wanted them to, we took that all on ourselves. We took a lot of pride in that sense, that this is going to be a lot of our hard work that makes this record. There was nobody to fall back on, we’ll make the success ourselves, and we enjoyed that aspect. And we weren’t worried about being super cool or what someone would expect us to do, which was kind of liberating.

It’s called Millennials. Why’s that?

The start of the process for me was just that liberation of moving to a new label. I wanted to make sure I’d not missed out on things I thought were too cool to sing about; to tap into places I felt I’d missed out, songs perhaps I’d forgotten to write. And from that all of these things started popping up. For me, Millennials is the idea of the highlights, the low-lights, and all the steps it takes to be where you’re at – even if you don’t know where that is. ‘Where are you? Are you happy? Are you feeling good?’ Immediately, it became this collection of songs for a general millennial figure in their life.

I think we’ve been lucky. We came along at a nice point. I’d hate to be starting our journey as an artist right now. That would terrify me. We’ve been lucky that our art’s always been super people-based. Before we decided to be recording artists, we wanted to be a band that plays on a stage and people connect with. That was how we got music growing up, so everything The Snuts was people-based. This time round we were really able to tap into what it means to be human, where we’re from, where others are from, and what the similarities are; what kind of qualities and fears do we all share.

You wrote most of these tracks whilst touring for your previous record, Burn the Empire. What was the process like of putting it together?

I think this time – again, because we’ve been through a couple of high-pressured records – we didn’t set out to even make a record, we just fucking made music in Scotland. We went to a studio up in the north, like at the foot of Ben Nevis – we had to get like a boat across. There wasn’t a pub there, wasn’t a shop, just fucking sheep and us. And the studio was amazing. So we went there, played some music, drank some wine, pressed the red button and just went to see if it was any good. We just wanted to make music for ourselves. Then the first track we played we thought, ‘This is quite good – we should build on this.’

We wrote maybe 50% of the record in Scotland then needed to go on tour, but were enjoying making it; because we did it in a stripped-back way – laptop, guitar pedals, drumkit, that was it – we realised we could do that anywhere. We didn’t need a three-grand-a-day studio that we’d had before – we probably never needed that.

So we took it on the road, and that pure urgency of being on the road, that lifestyle, town-to-town, side-to-side, all that energy was captured, bottled, and we stuck it into this record – high-energy, high-pace – tapping into how we were feeling; because being on the road is tremendous but it’s also fucking terrible. You feel everything. Even when you feel nothing, you feel it completely. So it was like, ‘Let’s get all this into this record, keep making this,’ we set a date and then that was that.

That ties into the context behind this album: it should really always just be a bunch of mates making music, but previously it wasn’t. What were the steps that led to you leaving your major label?

When we first signed our record deal, we were in such a different place, being an artist was such a different thing. Everything was really music-focussed; over the years of being at a major that just totally U-turned. I think you see that music’s a business, which it is. Everything comes from a personality base and like, ‘Let’s work on your personality,’ – personality first and then music can come after that. If they can get people to like you and the aesthetic, then you can bring the music into it. And for us that was so alien and uncomfortable–

And also defied what you’d previously shown, which was that people were really connecting to your songs…

For sure. It was a constant push-and-pull; we needed to stay true to what we were doing but then also had this pressure of what keeps us in the job. So the vision started to really drift apart. So much of the job now as an artist, I felt went against our ethics and morals. The second record, Burn the Empire, was all about pulling down the big corporations and how they control everything; we were making that record ‘cause that’s how we were feeling at the time.

And then we’d sit in the boardroom with it and they were like, ‘How do we sell this in a really clever way, to get one of your fans to buy five copies of this?’ I was like, ‘I don’t want one of my fans to buy five copies; we’ve just made this record and nobody’s got any money, we’re in the middle of a fucking economic crisis.’ I felt like I lost too much of myself and started being that guy in a sense. So the record for me was a big catalyst to realise we need to start thinking about what we want.

The label you set up is called Happy Artist Records – and there’s a reason it’s called that. Can you explain why that is?

Aye man, that’s a good one. Like I said, I don’t think we really knew what a recording artist was. We just wanted to be signed. As soon as we signed to Warner they put us in the studio. It’s in the basement of the Warner building; the Warner building’s got five labels in the building, so you can feel like the atomic energy in that building.

We’re in there, feeling really uncomfortable, making really shit music, and the head of the label comes down and says, ‘How do you feel these studio sessions are going? Are you happy?’ I’m rattling my brains, thinking, ‘Surely the right answer here’s ‘yes, we’re happy,’’ so I say that. And he just walks away and says, ‘There’s nothing worse than a happy artist.’ I’m thinking, ‘We’ll have a label one day, whether it’s ten year’s time, three year’s time, we’ll do it.’

And that helped build the mission statement of what we want to try and do with the label, to give people that place – young artists especially, because young artists I speak to now are genuinely scared to be an artist, scared to put music out, scared to express themselves because it’s so easy for people to disregard what they do, because there’s so much of it. People aren’t making the shit they believe in because it doesn’t “make sense” to make that record now.

They’re scared because of the personality side you say they need to cultivate?

Most artists I think are introverted. There are very few that aren’t like that. It’s the opposite of what your body’s telling you to do when someone says to you, ‘Go and be a reality star.’ So the idea for [Happy Artist Records] over the next couple of years is to create an actual safe space for people to come in, and say, ‘Alright, this is what I’ve got here and this is where I want to take it; this is what I want to become as an artist, and how do we do that?’ We’ll give the time, space and energy, and help with their social media – because you need someone to take that off you.

Speaking about the album itself and some of the tracks, ‘Gloria’ is about love in the everyday. How so?

I think you should always write from a pure place, so I wanted to do that and bring this semi-fictional quality to the track, to put my experience into a couple of other people’s bodies and tell it from the third-person, because that’s genuinely my story, man. I’m with the pure love of my life; it was never like this Hollywood story, we just came together in this pretty underwhelming circumstance. And we’re really content with what we are, and really happy with what we’ve got.

So many songs are the opposite of that, it’s like almost celebrating this hardship. So that was that track and we wanted to give it a name. I was watching silent films at the time – I do these weird things to get inspiration – and just as we’re thinking, ‘What kind of character can we name it?’ it just says ‘Gloria’. We sang it and thought, ‘That’ll do’.

Many of the themes on ‘Millionaires’ are similar; tackling love and how it triumphs over everything else. In some ways does that relate to your own journey leaving a major label?

I think so, man. I think when you’ve been in something for a while, like a job or anything like that, you start to lose the enjoyment a bit. I feel like as a society, there’s this idea that graft and success and money will bring happiness, but I don’t think graft and success always correlate financially. And you shouldn’t be disappointed when they don’t. There’s a comfortable place that you need to be happy. Too much is fucking crazy – you can be fucking miserable. We just want to be the absolute best version of ourselves. For me, everything I try to do is to be happy and more positive doing it. Those need to be hand in hand for me.

And what’s the final track, ‘Circles’, about?

Sonically, again it’s just summing up what we need to function, survive and be happy. I think we’re always waiting for disaster, thinking the whole world’s going to end. So it’s this post-apocalyptic thing in my head. We were watching an epic when we were doing it – one of those classics, Independence Day or Apocalypse Now – and the end scene when this dad puts the young daughter on the back of a motorbike and rides away trying to escape the impact. I was thinking about that person where it’s just you two together, at that moment.

The album is just under half-an-hour in length, it’s quite punchy. Was that a very conscious decision you made?

I think it’s totally a sign of the times. I think, perhaps subconsciously, the way we all consume music, including me as a listener, I just want everything to be happening. I think most people are quite guilty of short songs now. I would prefer it not to be like that but I think that’s the way we do it now. For this album, we cut a few tracks off to keep it to ten. We hit a comfortable amount of songs that I would like to have in my life. It’s weird man, these songs become my life and I need to go and fucking play them every night. So I better believe these. I need to feel those.

Before doing music full-time, you were a joiner, Callum [Wilson, bass] was a slater/roofer, Jordan [Mackay, drums] was a mechanic and Joe [McGillveray, guitar] had qualifications to be a stonemason… do you ever become quite taken aback at how far you’ve come?

Well that’s actually a joke there, man – Joe’s actually just a stoner, mate. One time we were describing our jobs [in an interview] and at the end of it, I just said, ‘Joe’s a stoner’ and they never took that down. How good is that? He’s just a stoner, mate. Most of the time I just let that one go by, that he’s a stonemason.

Stonemason, stoner – whichever it is – have you been able to take stock and enjoy how far you’ve come?

For sure, and that takes years to actually do that. All those demons and pressures build up inside of you, and you need to try and find the space to enjoy a lot of what you’re doing man; because you’re mostly so focussed on being successful, or more just holding onto it. It’s always been about progression with us. I’ve never been too stressed with the destination, but always about holding on and making sure it didn’t go anywhere, or I didn’t lose the love for it. So now, with this record, that’s gonna be the thing; we’re enjoying this, we’re doing it well, people are digging it, we have more say in what we need to be healthy and happy doing this. And all that shit takes work.

And now, of course, you can do all that on your own terms, with your own label…

I think so, that was quite a big thing; it was a big risk to do that, but it’s never once felt like we’ll be fucked. We’ve done all the heavy lifting – we know we did. What’s funny is [the major label] would probably love the way we are right now, and how open we are and the way we put ourselves into new circumstances. Sometimes you need to break away to be a better version of yourself.

We see that as a movement in music now – look at RAYE for instance, breaking a recent BRIT Award record after she left a major…

Absolutely, it’s across the board now. It’s a wave as well. It’s not like one size fits all with every artist; it doesn’t work where you have one model of someone doing something amazing and give that to someone else to do that. So it’s nice this wave is coming. I’m confident in my ability, I’m confident in people who like what I’m doing. I think it’s great. I think you’re going to see more and more of it.

And what’s next for you?

Keep on writing, get back into ideas. I’m a super 30% kind of guy. I’ll take something at 30% to the band and see if they can help me finish this and get this thing out. I think the thing about us is we’ll do something so different or be more selective and try and work with people that we love and put something together that’s even more massive.