“I’m just following the Irish tradition of songwriting, the Irish way of life, the human way of life. Cram as much pleasure into life, and rail against the pain you have to suffer as a result. Or scream and rant with the pain, and wait for it to be taken away with beautiful pleasure.” Shane MacGowan, 1997

Today’s news of Shane MacGowan’s passing shouldn’t be a shock to anyone who has seen the recent photographs shared by his wife, Victoria, but it’s a passing that will have taken the wind out of many sails. He has been a feature in our lives for 40 years.

He’s taught us about ancient Irish history and how Irish influence has played such a huge part in the growth of America. He’s also shown us how to laugh at our own failings. After all, this was a man who “gave the walls a talkin”. His work has introduced countless numbers of people to the joy that can be experienced through traditional Irish music and, even more so, the joy and camaraderie that can be experienced at his concerts.

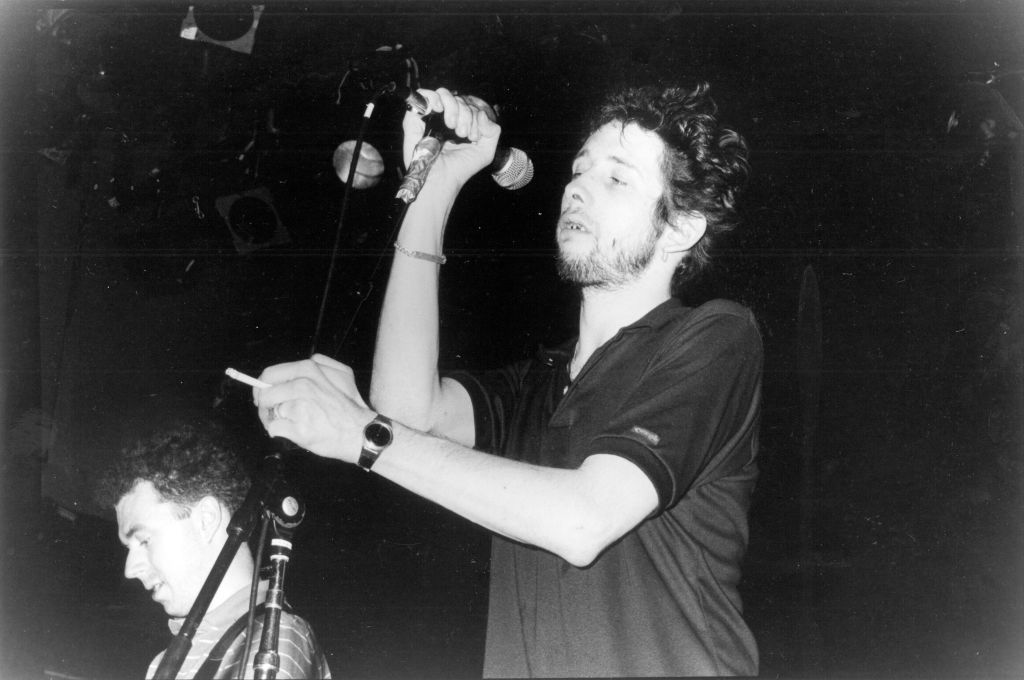

The reunion gigs at Brixton Academy were like no other concert I’ve ever attended. All walks of life were in the theatre, but everyone was your instant friend because you were all there for the same reason: to party with the help of The Pogues.

Born in Kent, he spent his first weeks sleeping in a drawer in his aunt’s bedroom before the family returned to their farmhouse in Tipperary, where he lived until age six.

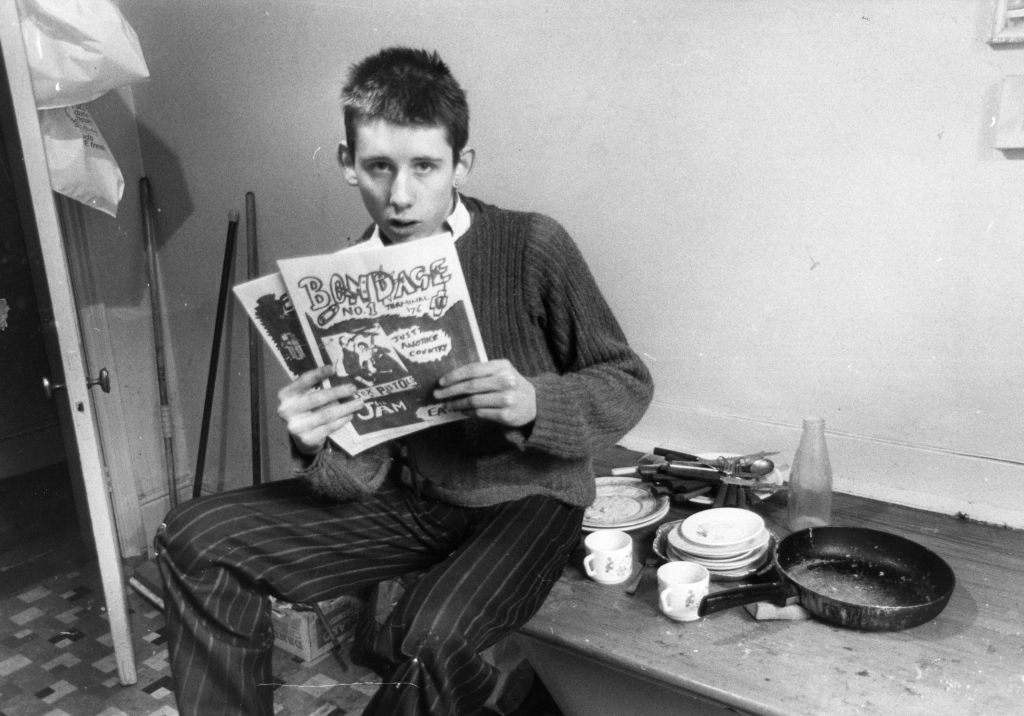

An early indication of Shane’s sharp intellect was demonstrated by the fact he was awarded a scholarship to Westminster School, one of the oldest and most prestigious schools in London. He sometimes would make an appearance until he was expelled for drug use. His parents, both academics, instilled in him a love for literature and music, and the MacGowan household was a melting pot of creativity, with traditional Irish folk tunes blending seamlessly with the rebellious spirit of punk rock that was gaining momentum in the late 1970s, by which time the MacGowans were back living in London and Shane was a well known ‘face’ on the punk scene in London.

This punk scene of the late 70s coaxed MacGowan away from a string of temporary jobs and led first to the formation of the punk band The Nipple Erectors. But it was with The Pogues (full name Pogue Mahone, the anglicisation of the Irish Gaelic póg mo thóin, meaning “kiss my arse”) that he truly made his mark.

Formed in 1982, this folk-fuelled punk throng was to become the bedding for dozens of offshoot musical genres, from Celtic themes from Led Zeppelin in England across the Atlantic to hardcore bands like The Dropkick Murphys.

They hit the ground running, and throughout the 80s, up until 1991, Shane was the principal lyricist in the band and was able to draw on a huge amount of historical knowledge (where else would you hear 12th-century Irish poetry quoted in the same song that mentions the Mỹ Lai massacre?). MacGowan would describe the music his band created as ‘guts balls and feet music… frenetic dance music it handles all sorts of subjects, from rebel songs to comical songs about sex’.

In 1991, Shane parted ways with the band; his behaviour had become too erratic, and Joe Strummer took over duties at the helm of The Pogues. Following his departure, Shane embarked on a solo career, releasing albums like The Snake (1995) and Crock of Gold (1997). While these solo ventures showcased his continued lyrical brilliance, MacGowan’s personal battles persisted. His ongoing struggles with addiction and health issues were well-documented, casting a shadow over his creative endeavours.

But it wasn’t without pushback. In a quixotic quest to conquer his addictions, Shane found himself a frequent visitor to the therapeutic sanctuaries of the Priory clinic in the heart of London and the St John of God retreat in Dublin. Yet, despite these earnest efforts, the lure of potent prescription tranquillisers and copious amounts of Martini remained unshaken.

In a somewhat dramatic twist, the year 1999 saw his contemporary, the singer Sinead O’Connor, alerting the constabulary, having discovered MacGowan in what appeared to be a heroin-induced stupor. MacGowan, however, dismissed the episode as a mere relaxation session with a gin and tonic, leading to no subsequent legal entanglements.

Notably, towards the end of the 1990s, MacGowan found himself somewhat adrift in an Ireland transformed by an economic boom. The nation, now basking in the glow of its newfound prosperity, dubbed the ‘Celtic Tiger’, seemed incongruous with the boisterous, alcohol-infused themes that pervaded his music. MacGowan, with his inimitable vocal style, had become a relic of a bygone era, a living embodiment of Ireland’s storied tradition of the inebriated bard.

READ MORE: Sinéad O’Connor | Nothing compares to one of the true few anti-conformists

Yet, in a twist of fate, 2001 heralded the reunion of the Pogues, a collaboration that persisted until the year 2014. When quizzed about the band’s status post-reunion, MacGowan wryly noted, “We’re not, no… we grew to hate each other all over again… We’re friends as long as we don’t tour together.” This reunion, although fleeting, was a poignant reminder of the group’s enduring legacy in the annals of music.

2015 was a year of significant personal challenges for MacGowan. A fall while exiting a studio in Dublin resulted in a fractured pelvis, necessitating the use of a wheelchair. This was also the year he underwent a rather monumental dental reconstruction – a veritable “Everest of dentistry”, as described by the attending surgeon – which included fitting a gold tooth, a nod, perhaps, to his flamboyant character. It was in this period, marked by physical rehabilitation and dental transformation, that MacGowan declared his departure from the world of alcoholic indulgence, a significant turning point in his personal saga.

Long-time friend and collaborator Nick Cave had this to say on the words Shane put to music: “He has a very natural, unadorned, crystalline way with language. There is a compassion in his words that is always tender, often brutal, and completely his own.”

Shane’s songs, often chronologies of Irish history, diaspora experiences, and the gutsy reality of London life, especially from a mistrusted and stereotyped Celtic perspective, seized the hearts of a generation.

His work with The Pogues, including the unforgettable ‘Fairytale of New York’, showcased his ability to capture complex emotions in lyrics and melody, twisting them into something new entirely. There really is no other Christmas song like it – no other song, in fact. Featuring the Anglo-Celtic darling of Britain’s New Wave, Kirsty MacColl, it remains perhaps the only Festive tune that other artists don’t dare cover, which says something.

As Bruce Springsteen said: We’ll be listening to Shane’s songs in 200 years’ time. His contribution to the world has been extensive, not just musically, but he’s introduced Irish traditions and culture to an audience that wouldn’t otherwise have had the pleasure, and on a personal level, his work has given me countless hours of joy, of melancholy, and of course, history lessons.

These lines from the tender and sweet ‘Lullaby Of London’ sum up how I feel right now –

May the ghosts that howled ’round the house at night

Never keep you from your sleep

May they all sleep tight down in hell tonight

Or wherever they may be

Keep up to date with the best in UK music by following us on Instagram: @whynowworld and on Twitter/X: @whynowworld