“Little Johnny Jewel / He’s so cool / He had no decision / He’s just trying to tell a vision”. The opening lyrics to ‘Little Johnny Jewel’, Television’s debut single, released in 1975, might be a clue to the way Tom Verlaine saw himself and his band. Verlaine, Television’s founder, guitarist, and sole songwriter, died on Saturday, aged 73, after a short illness. Television and Verlaine’s music embraced contradictions. It continually seemed to be seeking an undiscovered way, always just ahead.

Though always cited as one of the key players in the birth of punk, Verlaine’s sensibility consistently leant more to jazz and classical than rock, and certainly punk. He once described the genre as “just amped-up bubblegum with angrier lyrics”, and it was probably always too earthbound for Verlaine. His lyrics are full of raw and overawing imagery – the ocean, flight, the vast, strange world of the night, and, of course, the moon – a mysterious blend of fright and yearning; his ghostly, strangled yelp of a voice carries the air of a hounded animal.

Yet, Verlaine and his one-time friend and bandmate Richard Hell – born Thomas Miller and Richard Meyers, respectively – have as much of a plausible claim to being punk progenitures as anyone else, and are indelibly associated with its birth as a movement. Both born in 1949, they met at private school in Delaware. Discovering their shared passion for music and poetry, the two became close, and inspired their heroes – French poets and literary proto-punks Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine – they fled school together for the big city.

Sad 2 hear of @TELE_VISION_TV #tomverlaine passing today. He made incredible music that greatly influenced the US & UK punk rock scene in the ‘70’s RIP pic.twitter.com/hbntmsLqMm

— Billy Idol (@BillyIdol) January 28, 2023

After one failed attempt involving a midnight campout in a field and a farmhouse accidentally being set on fire, they finally made it to New York. Changing their names in an act of homage to their heroes (Hell likely inspired by the teenage Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell and Verlaine naming himself after the older poet ‘purely for the sound’ of the name) they imitated Bob Dylan’s act of reinvention and set out to make a new kind of music.

Though they formed what would become Television together, the two friends could not, it turned out, have been more different – especially in their attitudes to artmaking. Hell was wild and provocatively nihilistic: playing the rudimentary bass which Verlaine taught him, he threw himself around onstage, wearing a t-shirt which read “PLEASE KILL ME”.

Verlaine was always much more interested in art than attitude. “Attitude will only take you so far,” he commented, “which for me is never far enough.” Hell would messily slash and spike his hair and safety-pin his clothes in sartorial homage to Rimbaud. Malcolm McLaren pinched this style to give to the Sex Pistols, and a whole pretty vacant and blank generation followed.

After a short-lived early incarnation as the Neon Boys with drummer Billy Ficca the group disbanded, then reformed, having found their magic ingredient: second guitarist Richard Lloyd. He was a musician who could match Verlaine’s skill and vision on his instrument. Looking for gigs, Verlaine approached a ‘country, bluegrass, and blues’ club which, naturally enough, went by the acronym CBGBs. He lied and told them that this was the kind of music his band played. Once they were in the door, other artists swiftly followed, Verlaine’s sometime lover Patti Smith and the Ramones among the first. CBGBs swiftly shed its identity as a country, bluegrass, and blues club.

Verlaine’s sometime lover Patti Smith is among those to have paid tribute to the late musician; once Television were through the door at CBGBs, the likes of Smith soon followed. Photo: Suzan Carson/Michael Ochs

From the freshly rebellious attitude of Hell (whom a frustrated Verlaine kicked out of the band in 1975) to their sullen, cold, and severe aesthetic, to their role in turning CBGBs into the mothership of punk, Television left a hefty legacy within a genre whose confines they never quite fitted into.

Released in 1977 – the same banner year as other debuts by the Sex Pistols, the Clash, Wire, and the Ramones, to name just a few – Marquee Moon looks way, way ahead. A lot of its unclassifiable brilliance is down to the always distinct yet shape-shifting guitar work of Verlaine and Lloyd: livewire, flashing by in turns of tone from chunky and crunchy to jangling and diamond-edged, in music vicariously swinging between cut-throat riff and careening jam, forever about to veer off-course yet stabilised by a precision that can seem almost classical at times – an invisible logic.

From a young age Verlaine was drawn to jazz, gravitating toward the harmonically complex explorations of John Coltrane and the similarly cosmic free jazz experiments of Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman in the ‘60s and, later, the electric period work of Miles Davis in the ‘70s.

The miracle, most evident on Marquee Moon, is how Verlaine intuited some mysterious middle path between styles: his playing, and the meticulous, trembling structures of the music are somehow balanced between the improvisatory ecstasy of Coltrane, Coleman, Ayler and Davis, the tight and satisfying song structures of the Stones, and the jammy psychedelia of West Coast hippie contemporaries The Grateful Dead. It produces a wholly original, majestic edifice of guitar rock, all laced with something of the ironic, self-aware sneer of punk.

Television’s debut album, Marquee Moon.

This heady mix, seemingly unworkable yet undeniable in its perfection, has inspired bands as varied as R.E.M., U2, Sonic Youth, the Feelies, Echo & the Bunnymen and Siouxsie & the Banshees. The two ‘70s Television albums, Marquee Moon and 1978’s follow-up Adventure (they also released an excellent third record in 1992, the self-titled Television), are in the same realm of significance as the four records made by The Velvet Underground. Go deep enough on any song and you’ll hear whole new genres and sub-genres stirring, slouching, moodily, to be born.

The progeny of rock n’ roll, surf rock, punk rock: this musical line leads (if we must categorise these styles something, which we must) onto alternative rock, indie rock, college rock, math rock, and whatever post-punk means now. Listen to a couple of contemporary explorers of this space – say, black midi or Black Country, New Road, to name two well-known British examples – and you’re listening to the space in rock music that Television kicked open.

After only their second album, Adventure, in 1978, and a bad tour as a support act for Peter Gabriel, Television broke up. Verlaine thereafter plotted a career path that was defined, as he himself put it in a 2006 interview, by “struggling not to have a professional career”.

He went his own way, beginning with the self-titled solo album Tom Verlaine in 1979. He continued to make singularly great rock songs – the instrumental breaks on the perfect album-closer ‘Breakin’ in My Heart’ approach the ecstasy of Marquee Moon – but he was always much more interested in experiment than in accomplishment or fame.

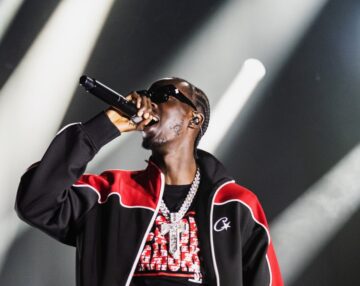

Tom Verlaine performing in 2008. Photo: Stephen Lovekin

listened to Marquee Moon 1000 times. And I mean LISTENED, sitting still, lights down low taking it all in. awe and wonder every time. Will listen 1000 more. Tom Verlaine is one of the greatest rock musicians ever. He effected the way John and I play immeasurably. Fly on Tom.

— Flea (@flea333) January 29, 2023

He retreated from the spotlight, working steadily and meticulously on music that met his own standards and cared not for anyone else’s post-Television yearnings. He scored silent films, toured, and collaborated with Sonic Youth, Smashing Pumpkins, Violent Femmes, Luna, Patti Smith, Bob Dylan, Jeff Buckley, and others; he formed part of the supergroup Million Dollar Bashers; and, in the ‘90s and 2000s veered in a more instrumental direction with two gorgeous instrumental albums, 1992’s Warm and Cool and 2006’s Around, which would, it turned out, be his last.

Though Television reunited in the ‘90s to make a new and hugely enjoyable comeback record, and toured sporadically thereafter, co-guitarist Richard Lloyd eventually left the band for a second time, citing his frustration that Verlaine proved incapable of producing new material fast enough. An unfinished new Television record apparently lies in the vaults.

The reverence in which Verlaine’s fellow musicians hold him has been evident in their social media tributes. Michael Stipe of R.E.M wrote of Verlaine’s “rigorous belief that music and art can alter and change matter, lives, experience.” Flea, meanwhile, tweeted: “listened to Marquee Moon 1000 times. And I mean LISTENED, sitting still, lights down low taking it all in. awe and wonder every time [sic]. Will listen 1000 more. Tom Verlaine is one of the greatest rock musicians ever. He effected the way John [Frusciante] and I play immeasurably. Fly on Tom.”

Verlaine’s intensity of vision and purpose in making music outside boundaries is rare over any career, an example to any artist today in a cultural landscape built on clicks and streams. As he hinted in Television’s debut single, he had to tell a vision – and he kept at it, in his own way. In the words of Patti Smith’s tribute: “Farewell / Tom, aloft / the Omega.”