Strasbourg 1518 is the latest short from Jonathan Glazer, the British director, whose work includes Birth (2004), Under the Skin (2013), as well as countless visionary music videos and adverts. A defiant and charged response to life under lockdown, the film takes off from the ‘dancing mania’ that overtook what is now a French border town, but what was then part of the Holy Roman Empire. This mysterious event saw between 50 to 400 people dancing day and night, and it is rumoured that some danced themselves to death.

I can’t imagine a much better subject for visionary director Jonathan Glazer than mass hysteria, and more specifically the dancing plague of Strasbourg in 1518. We know very little about the etiology of mass psychogenic illness: some speculate the infamous outbreak of dancing was the result of food poisoning caused by the psychoactive chemical products of ergot fungi, while some speculate widespread stress-induced psychosis. No-one really knows.

Yet the image of hundreds of people dancing for days at a time, unable to stop, is a compelling one. Amusing, surreal — undoubtedly, horrifying. This true story of dancing mania is as infamous today as it was hundreds of years ago, and it’s ripe territory for Glazer, a director who has staked his career on elegantly simple conceits, arresting if ambiguous images, and cathexis in both form and subject matter: troubling manifestations of irrational behaviour.

White walls that appear grey and granular, as if you’ve woken up in the middle of the night and your eyes are still adjusting.

Strasbourg 1518 opens with a woman in a poorly lit room. Plug sockets. White walls that appear grey and granular, as if you’ve woken up in the middle of the night and your eyes are still adjusting.

This exhausted-looking woman puts her face in her hands and begins to turn. Spins, until she is resting in the corner of the room. ‘How are you?’ she asks. ‘From ten to one?’ She rolls her shoulders. Windmills an arm — or rather her arm rotates, despite herself. She laughs.

The great dancing plague of 1518

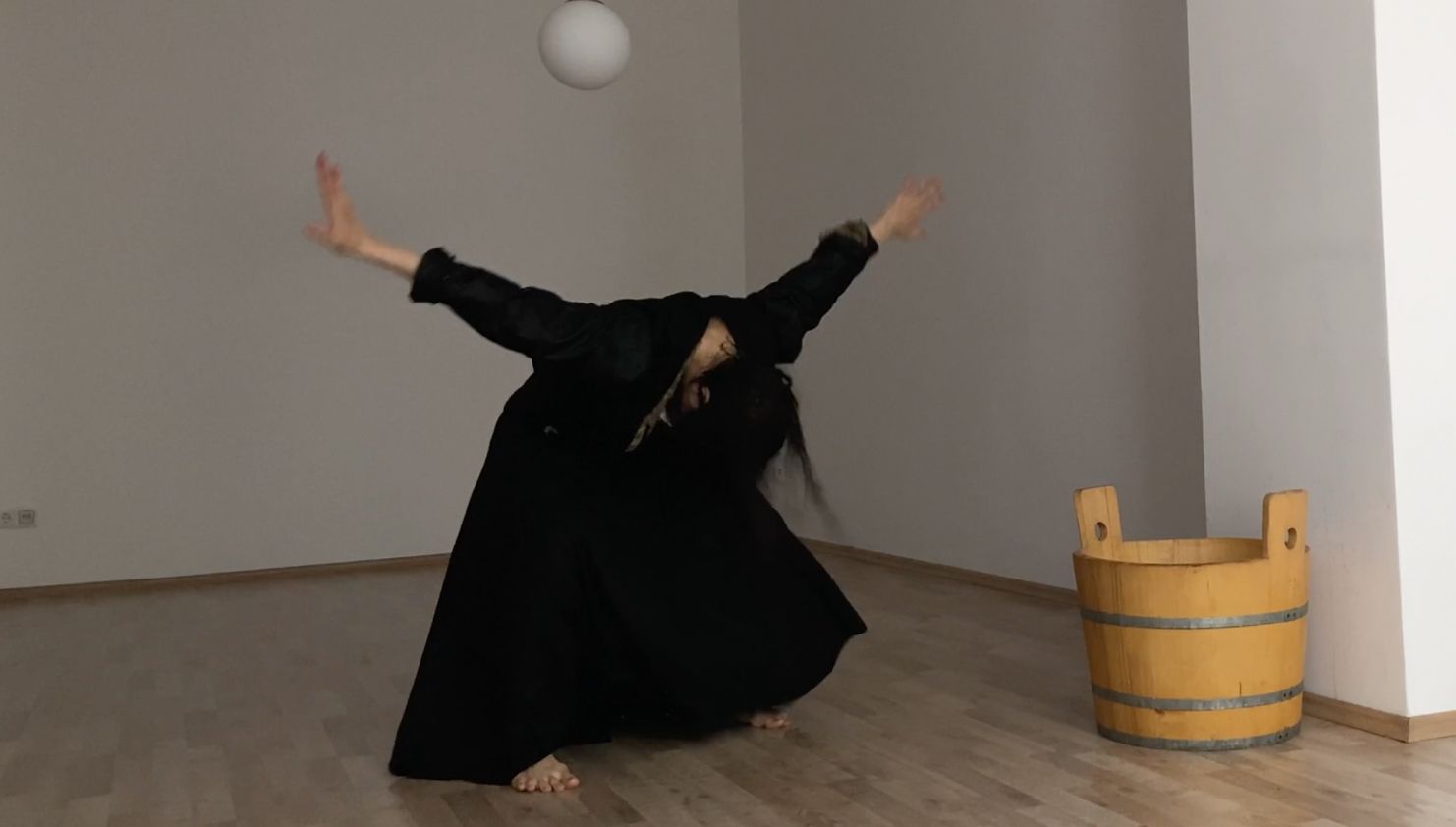

Cut, and cue the relentless pounding of an industrial breakbeat by Mica Levi, as another woman in a bare, studio-flat-sized room claps, twists, and stomps next to a pail of water (the only direct allusion to medieval Strasbourg throughout). Here, she frantically washes her hands.

As she moves about the room, traces of this hand-washing gesture remain, mutating; chaos flows through the dancer’s body and her hands attempt to contain it, perhaps even define it. This is fluid if desperate dance that seems composed entirely of obsessive tics.

She pants and grunts from exhaustion, but then her body violently flips again and her wet hair and hands stick to a different part of the wall.

The white walls offer a moment of reprieve when the woman clatters against them. She pants and grunts from exhaustion, but then her body violently flips again and her wet hair and hands stick to a different part of the wall. Meanwhile, the breakbeat won’t let up.

Cutting between rooms, each as spare and bare as the last, we encounter nine dancers in total — but they might as well be the same person. Each moves as if they are moving against his or her will, bodies lunging and lurching.

Distorted strings yammer, radio-tuning sound effects fade in, blur into birdsong, fade out again, as the bass pummels on. The cuts get faster, flickering from room to room, body to body, stroboscopically. I find myself rocking from side to side in my chair.

A dancing plague that has been lying dormant since the 16th century has come back to infect our present time of lockdown and contagion. Of course, you could say that Strasbourg 1518 is about epidemics that rhyme and reemerge across time; but that would seem to limit its effects, which are visceral and intuitive. Why not simply say that the film is an experience, one that passes from body to body, from filmmaker to viewer?

Glazer’s oeuvre has so far been propelled by a radical trust in imagery — mercurial images that sometimes bypass the intellect and make their own poetic sense. What might seem surreal or alterior about the director’s visual language is mediated by the grimy detail; tactile physicality makes concrete (if uncanny and ambiguous) some yet to be defined real world emotion.

Working within a basic sequence of events, Glazer seems concerned with repetition and variation, iterative time favoured over cause and effect per se (indeed, one of the experiences the director seems interested in capturing on film is that of people not really getting anywhere, humans like wheels churning in mud).

At the same time, those dancers are all of us locked down in our homes.

In Strasbourg 1518, we have a haunting image in the title card; it’s synecdoche for an entire town dancing for days on end, and for mass hysteria in general. At the same time, those dancers are all of us locked down in our homes. While the mood might seem dream-like, it’s those bare plug sockets, light fittings, urban streets glimpsed through windows, and the slap of feet on faux-wooden floors that root us in the material world.

The image of ceaseless dancing behind closed doors is repeated, transformed, and with each iteration begins to read like death-drive (which recalls the panting, sweating man chased by Thom Yorke in a plush car in Glazer’s 1997 music video for ‘Karma Police’.)

Glazer followed Under the Skin (2013) with a seven-minute short (also currently available on iPlayer) titled The Fall (2019). In many ways, Strasbourg 1518 picks up where that film left off. The Fall is a Kafkaesque allegory of mob mentality, of a man almost lynched in a near-bottomless pit, which nonetheless alludes to events in the real world. In relation to this film, Glazer told The Guardian, ‘The rise of National Socialism in Germany for instance was like a fever that took hold of people. We can see that happening again.’

You both do and don’t want Strasbourg 1518 to end, you want it to stop, you need it to continue — perhaps because, like the dancing plague itself, this film is both ‘like a fever’ and like its cure. It’s the vital release of unseen tension and fear, a manifestation of the invisible and the concrete: the ghost of the nation — or a previous or possible nation — caught in the machine.