Bruce Springsteen lived up to his nickname, ‘The Boss’ last year, by topping the list of the highest-paid musicians for 2021, as the sales of back catalogues saw a boom in revenue for the music industry.

Bruce Springsteen (right) jams with Paul Simon – both artists were reportedly in the top 10 highest-earning musicians in 2021. Photo: Vinnie Zuffante/Michael Ochs Archives.

The world’s 10 highest-paid musicians last year raked in a combined $2.3billion, approximately double what they were typically making in recent years.

It seems somewhat extraordinary that in a year still beset by coronavirus woes, with touring schedules largely ripped up yet again, musicians were able to not just bring in the same revenue but smash their usual earnings.

Yet for anyone who’s been following the music industry closely, the answer is far less surprising. That’s because the sale of artists’ back catalogues: the rights and ownership of their previous works being auctioned off at a serious pace.

From Bob Dylan to Taylor Swift, and, even more recently, David Bowie, these sales have become more and more common, with BMG, Warner Chappell Music and Hipgnosis among just some of willing buyers.

Bob Dylan’s back catalogue is thought to have cost nearly £300million.

And now, thanks to some nifty reporting from Rolling Stone’s Zack O’Malley Greenburg, whose added public documents with information from industry insiders, we’re able to see the benefactors of these large deals and just how much the highest-paid musicians of 2021 reportedly made:

- Bruce Springsteen ($590 million)

- Jay-Z ($470 million)

- Paul Simon ($260 million)

- Kanye West ($250 million)

- Ryan Tedder ($200 million)

- Red Hot Chili Peppers ($145 million)

- Lindsey Buckingham ($100 million)

- Mötley Crüe ($95 million)

- Blake Shelton ($83 million)

- Taylor Swift ($80 million)

- Neil Young ($78 million)

- The Rolling Stones ($75 million)

- Shakira ($65 million)

- Tina Turner ($62 million)

- The Eagles ($61 million)

A number of things are striking from this list, notably how just three woman are in the top 15, and just one (Taylor Swift) in the top 10.

Indeed, aside from the two rap stalwarts Kanye West and Jay-Z, much of this musical rich list consists of older rockers cashing-in on their past work, which again feeds into the lack of diversity among this roster of wealth.

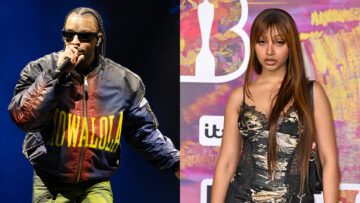

Kanye West, or Ye, was one of the only rappers on the list of the highest-earning musicians in 2021.

This begs the question – which, as you’d expect, we ask all day every day – why now? Why have some of the music elites chosen now (or, 2021, to be precise) to sell off the rights to their life’s work?

As with most things, three aspects help tell the tale: the artists, the labels (or buyers), and us, the people. Each of these, of course, were under the same umbrella of the pandemic.

First, the artists. With the obvious unpredictability of live shows going ahead or not throughout a socially-distanced age, musicians were inevitably looking for something more than their streaming income alone – which can often seem a pittance. One estimate puts a single Spotify stream as equal to just £0.004.

That said, 2021 wasn’t entirely suppressed or in lockdown (unlike the tedium of 2020 from March onwards) and indeed some tours did go ahead, as we learnt to ‘live with the virus’. The Rolling Stones, for instance, put on their rescheduled No Filter Tour – a 13-date showstopper that began in Missouri and ended in Austin.

The Rolling Stones performing in Las Vegas, Nevada as part of their No Filter tour. Photo: Ethan Miller.

Like the good ol’ pre-covid days, this grossed a reported $115.5million, roughly half of which ended up with the band themselves – helping to establish them as the only British act in 2021’s musical rich list.

Yet overall, those unable or simply unwilling to play a show that may easily have been cancelled at any minute, were after other forms of revenue.

For the buyers, record low interest rates in response to the pandemic made borrowing such large sums required to buy back catalogues (Bob Dylan’s alone cost nearly £300million), cheaper than usual.

It’s been a shrewd piece of business too. In its interim financial report, music IP and song management company Hipgnosis, for instance, reported that its portfolio consisted of 146 catalogues, or 65,413 songs, amounting to an aggregate value of $2.55 billion (£1.87 billion).

Taylor Swift was one of the only women on the list of highest-earning musicians in 2021. Photo: Dimitrios Kambouris.

The London-listed company therefore owns the rights to every single one of these songs, gaining revenue for every stream. There may be question marks over how much streaming is worth, but when over 65,000 songs are played in the millions, it’s worth a pretty penny.

Net revenue for the company was reported as being 31% higher compared to the previous year: specifically, $74.1million in the six months to September, compared to $56.7million earned in the same period the year before.

And just as artists will observe other artists selling their catalogues for millions, creating a domino effect of sales, the competition between major music companies and newer startups has led to even more acquisitions.

Precisely why the ownership of old songs is now such big bucks is then down to the final part in this money-making tripartite: us, the consumer, or listener. Whether it’s because of our desire to hark back to simpler times during a challenging couple of years, or because they just don’t make them like they used to, our consumption of older songs has increased and looks like it will continue to grow.

2021 was the first year since at least 2008 that the consumption of current music declined, as we listened to more catalogue music.

Based on statistics from MRC Data, and published in Music Business Worldwide, the consumption of catalogue music accounted for an incredible 73.1% of music consumption in America, with the remaining 26.9% being current music (classified as music released less than 18 months ago). And whilst this was just the US market, it’s a huge barometer on the consumption of music at large.

Indeed, 2021 was the first year that the consumption of current music declined, ever since MRC Data first started tracking streaming music in 2008.

All of this then is music to the ears of both the artists and the buyers, making 2021 not only the year of the back catalogue sale, but also making Bruce Springsteen a very wealthy man.