Could the game industry’s zest for increasingly beautiful and complex game worlds be damaging the future of the medium?

Late last year, you may have found yourself spending some time meandering around the vast and mind-bogglingly detailed city showcased in the Unreal Engine 5 tech demo released to coincide with the launch of The Matrix Awakens.

As technical achievements go, this richly-detailed environment is deeply impressive, and having experimented with its real-time lighting effects and checked out the unabashed majesty of its long-distance rendering, you’d be forgiven for excitedly thinking that this is what triple-A gaming of the future looks like.

And you’d be right – but not, perhaps, in the way you think.

Whilst The Matrix Awakens tech demo is undoubtedly an amazing technical achievement, it also unintentionally points to a worrying side-effect of modern high-end game design: ultra-detailed ‘open’ game worlds that are ever more complex and richer in visual fidelity, but offer increasingly little of note to do within those worlds.

Granted, in The Matrix Awakens, this is the point, as the experience is a technical showcase and little more. But whilst wondering around those immaculately-detailed streets, it’s both ironic and striking that regarding microcosms, unless triple-A gaming development takes a radical turn, the beautiful yet empty world of The Matrix Awakens is the logical fate that eventually awaits all high-end open world environments.

Look at the troubled 2020 hit Cyberpunk 2077 for example. The world of that game itself is shimmeringly gorgeous on the new generation of consoles, and promises to be more so, when the long-awaited dedicated Xbox Series S/X and PlayStation 5 versions of the game finally arrive. But whilst Night City may look pretty, you don’t have to peek far beyond the aesthetic to see the beautiful illusion collapse in on itself. Beyond a few outfit vendors, weaponsmiths and cyberdocs, there’s precious little to actually do in the game world beyond mainline quests and enjoying the view. A pale imitation of life, that is visually impressive, but little else, even when compared to open world games of previous generations.

Sure, Lionhead’s Fable III may hail from a couple of console generations ago, but the argument can easily be made that Albion, the game world in which the action takes place, is teeming with far more life than 2077’s Night City will ever muster, no matter how many patches developer CD Project RED puts out.

Cyberpunk 2077

The Billion-Dollar Pie

This arms race towards technical perfection isn’t just hurting the quality of triple-A gaming, it’s also had a crippling effect on the frequency of high-end games we can enjoy.

Between 2004 and 2010, the aforementioned Fable series managed to release three original games (not to mention a remaster of the original), and whilst critics might point to a lack in innovation across the saga during this time, sales and critical reception remained consistently good, whilst the core fanbase was happy. They also got more Fable. Compare that to the way top-end game development has changed in the decade since, and the idea of getting three open world titles from a single developer in six years, has become unthinkable. But why?

The answer, to quote the Sean Parker character from The Social Network, is that ‘a million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A billion dollars.’

Red Dead Redemption 2

Monster-selling triple-A titles like Rockstar Games’ Red Dead Redemption 2, for better or for worse, have altered the top-end gaming landscape irreversibly. With the sales of Rockstar’s GTA V currently sitting north of 120 million (all three Fable games combined sold somewhere around 20 million in total), the billions that Rockstar has banked from its open world titles has every major publisher determined to create their own rich, detailed and vast gaming environments.

Of course, this approach does not come without its drawbacks. Developing triple-A titles of the scale, fidelity and complexity of GTA V or Red Dead Redemption 2 comes at a significant cost, and one we all, unfortunately, have to pay.

For one, frequency takes a hit, with development cycles ballooning, often by years, to accommodate games that are constantly aiming to be bigger and shinier. Rockstar’s protracted development cycle for 2018’s Red Dead Redemption 2 was believed to be eight years, worth it perhaps for those that enjoyed the final game and its undeniable levels of polish, but less so for those of us who remember when Rockstar put out three stellar GTA titles (GTA III, GTA: Liberty City and GTA: San Andreas) in the space of just five years.

Size isn’t everything

You could argue that a single Red Dead Redemption 2, with all of its gloss and dizzying scale, is worth three mid-2000s GTAs, and perhaps you’d be right. But if you’re old enough to recall the continued sense of joy those five years brought for fans of open world titles, you wonder if there isn’t a middle ground, where compromise could be sought between technical innovation and frequency of releases.

Whilst it’s doubtful that anybody is pining for games to be further infiltrated by the sort of annual incremental tweaks we’ve come to expect from some EA sports and shooter titles, when it comes to narrative games, perhaps the pendulum has swung too far the other way, reaching a point where scale is valued over quality.

Last year’s announcement from Techland, the developer of the recently-released Dying Light 2, is a perfect example of this. The developer’s widely-reported claim that you’d need to set aside ‘at least 500 hours’ to complete all of the game’s content was met with fan reaction that was far less positive than Techland were presumably expecting it to be. To the point that it would swiftly issue a clarifying statement, explaining that the main storyline quest comprises around 20 hours, with side quests tallying up to 80 hours or so.

The other 440 hours? Well, if history is anything to go by, you can probably guess. Fetch quests, collectibles, content that is often largely meaningless, designed purely to pad out the experience to assure the player that they are getting their money’s worth.

Whilst Techland was simply trying to generate buzz for its forthcoming title amid a crowded gaming landscape, its lack of judgement in boasting about scale points to this wider problem with the medium, the misconception of game publishers that ‘size is everything.’

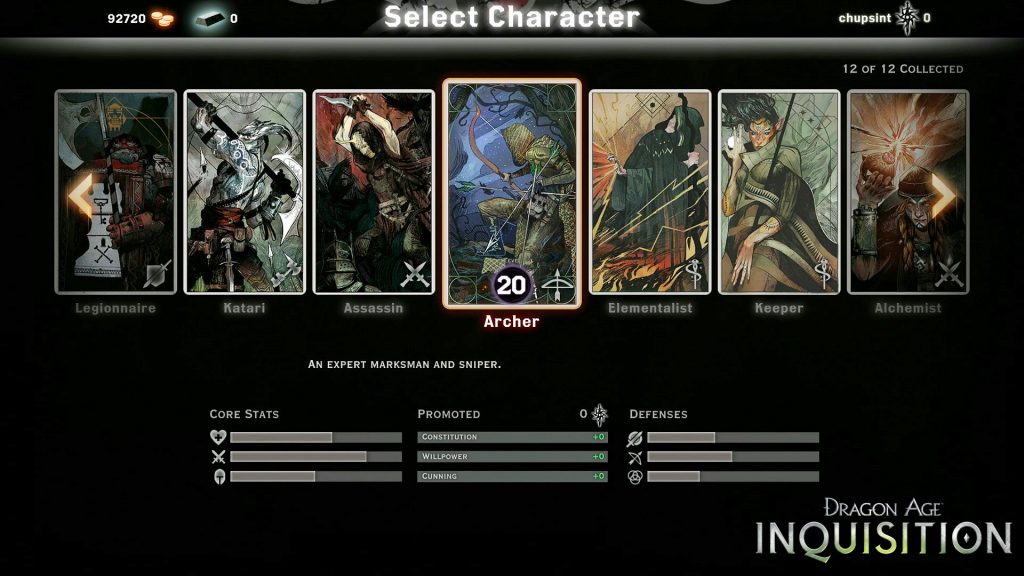

Dragon Age Inquisition

Along with Ubisoft, the developers of the Assassin’s Creed and Watchdogs series, EA is a key culprit in this regard, often impressing a need for scope upon its development teams, which in turn, leads to a whole host of problems.

The kind of scope EA demands for the bulk of its triple-A titles often comes in the form of both size, and revenue potential, as evidenced by the recent output of its RPG development team, Bioware: a textbook case of a company falling victim to a never-ending thirst for growth.

Bioware’s original vision for the currently-in-production Dragon Age 4 saw the company take on board the criticisms that its award-winning predecessor, Dragon Age: Inquisition, was too large, with the development team planning instead to make the fourth game smaller, but more ‘dense’ with narrative choice.

This approach, whilst exciting to fans of the series, did not sit comfortably with EA, who eventually sandbagged development of the game. It insisted instead that Bioware produce a game set in a larger open world, whilst adding in MMO-style elements, essentially reconfiguring a single-player narrative-based series into an always-online multiplayer experience. It’s a demand for growth in every sense of the word that would drag the series away from what had made it so beloved.

Ultimately, EA would abandon this approach in the wake of another game – Anthem – and its disastrous launch, a Bioware title that tried and failed to deliver as an MMO-based RPG. The damage, however, was done. The original, smaller, ‘less is more’ approach to Dragon Age series would not return.

Where’s the fun in that?

There’s an equally unsavoury side-effect to the triple-A trend for online worlds that video game genres continue to lean into, and that’s the drive for fidelity at the expense of fun.

Sure, the worlds that developers create may be increasingly beautiful, but they’re also increasingly empty, and increasingly buggy at launch at least, two problems resulting from the modern trend to release games in these questionable states. All with the intent of patching them with more content and bug fixes at a later point.

Like Destiny 2 before it, Cyberpunk 2077 is a particularly egregious example in this regard, with players still waiting for basic (and promised) features, such as changeable hairstyles and a functioning police chase system, over a year on from the game’s release.

Cyberpunk 2077

Likewise, the dearth of content plaguing Red Dead Online has recently led fans to stage a #savereddeadonline campaign, a predictably doomed venture when developer, Rockstar Games, has clearly decided the title isn’t worth supporting.

Essentially, what we’re seeing points perhaps to a wider societal problem: technological advancement simply for the sake of it. When you consider the technological advancements in cinema over the last 120 years or so, they seem profoundly simple compared to the progress made in video gaming in around half of that time period. Consider the meteoric journey from Pong to virtual reality in 4K, and whilst it’s clear that the medium has come a long way in a relatively short space of time, there is a cost attached to that.

As development cycles expand, in order to afford teams time to make triple-A titles bigger and shinier, publishers find themselves having to resort to ever more questionable ways to bring in income during these ‘development droughts’. Annual releases, cross-generation releases, paid DLC, micro-transactions and now the greatly-derided arrival of the NFT, not to mention the ‘sloppy remaster’ cash-in that Rockstar Games, and others, have resorted to, are all symptoms of a wider issue. The need for developers to cover and finance the widening development timeframes that blockbuster titles require.

Although the endless tedium of grinding and fetch quests, whilst enduring bugs and microtransactions, may be to the taste of some, many gamers are turning off. Both sales and player numbers have demonstrated this, with the recent and high-profile disaster that was the launch of EA’s Battlefield 2042. Triple-A gaming seems to be in danger of forgetting the core element of what gaming should be all about: fun. The increasingly standardised design of Ubisoft’s open world titles has long since supressed the sense of discovery and wonder that these types of titles used to evoke, and even the sandboxes themselves, are often not as fun to play in as they once were.

Fun in gaming, of course, often comes from that pleasant sensation of being surprised, another increasing rarity in triple-A game design. The homogenisation of high-end games development is clearly a factor here: as companies burn through ever-increasing, mind-boggling sums in the pursuit of technical perfection, the direction of these titles becomes inexorably more risk-averse, so as to protect the sizeable financial investment at stake.

Even Sony, whose collection of first-party PlayStation titles continue to be one of gaming’s ‘crown jewels’, is increasingly commissioning open world-style titles such as Horizon Zero West and God Of War: Ragnarok at the expense of other, less celebrated genres.

Chasing Perfection

Ultimately, the tantalising prospect of whether perfection is achievable in games, is perhaps the wrong question to ask. Instead, the conundrum of whether we should be seeking perfection at all is the line of thought that deserves our serious contemplation.

At the dawn of a new console generation, with all of the raw horsepower that affords developers, it’s almost certain that this ceaseless quest for digital verité will continue, but at what cost? Granted, Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption 2 may be the closest thing we’ve seen to a ‘perfect’ recreation of simulated life in an open world, but that game’s protracted development meant no Grand Theft Auto title for the last console generation. On top of that, the cancellation of a planned sequel to Bully, as Rockstar pulled more and more resources from the latter project’s development to pour into its incredibly ambitious open world Western.

Grand Theft Auto V

Surely this must be a concern for fans of high-end gaming, no matter where their loyalties may lie. As amazing as Red Dead Redemption 2 may have been, Rockstar produced exactly one original game in the entirety of the last console generation. Insiders have suggested that the coming generation might produce a similarly low yield. Naughty Dog, creator of the acclaimed Uncharted and The Last Of Us series produced two, compared to five the generation before.

Despite the teams above producing flat-out masterpieces, other developers have been less successful, facing similar challenges, toiling (and sometimes crunching) to produce huge, beautifully-realised digital worlds that then often need to be populated with content post-launch, or remain eerily empty.

On the whole, it’s an artistically-compromised process, not to mention a false economy, and the triple-A games sector is in desperate need of a new industry-influencing champion, in the form of a blockbuster smash hit that scales down in size and length, perhaps being more feature-dense, as Bioware’s Dragon Age 4 (or Project Joplin as it was codenamed) was set to be.

Until then, expect the game worlds created by blockbuster developers to arrive, perhaps, once in a decade. Should they manage to be realised with any greater frequency than that, it’s likely they’ll bear more than a passing resemblance to that gorgeously-rendered Matrix Awakens tech demo: an aesthetically-perfect imitation of life… just, without the life.