When Johnny Cash walked into Folsom State Prison on 13 January, 1968, the man in black was weathering his darkest days. His first wife Vivian Liberto finished divorcing him just months earlier, he was desperate to bounce back after overcoming his drug addictions, and not one of his songs had seen the American Top 40 in four years. Then the two shows he played, and recorded, in that penitentiary changed everything.

55 years after its release, At Folsom Prison is hailed as one of the true great albums. “That’s where things really started for me again,” the country king told Rolling Stone in 1973. After teetering on the precipice of a downfall, he reclaimed his commercial power with the live single ‘Folsom Prison Blues’. Then, the gravel-voiced solemnity of the entire LP went on to rattle heartstrings for decades.

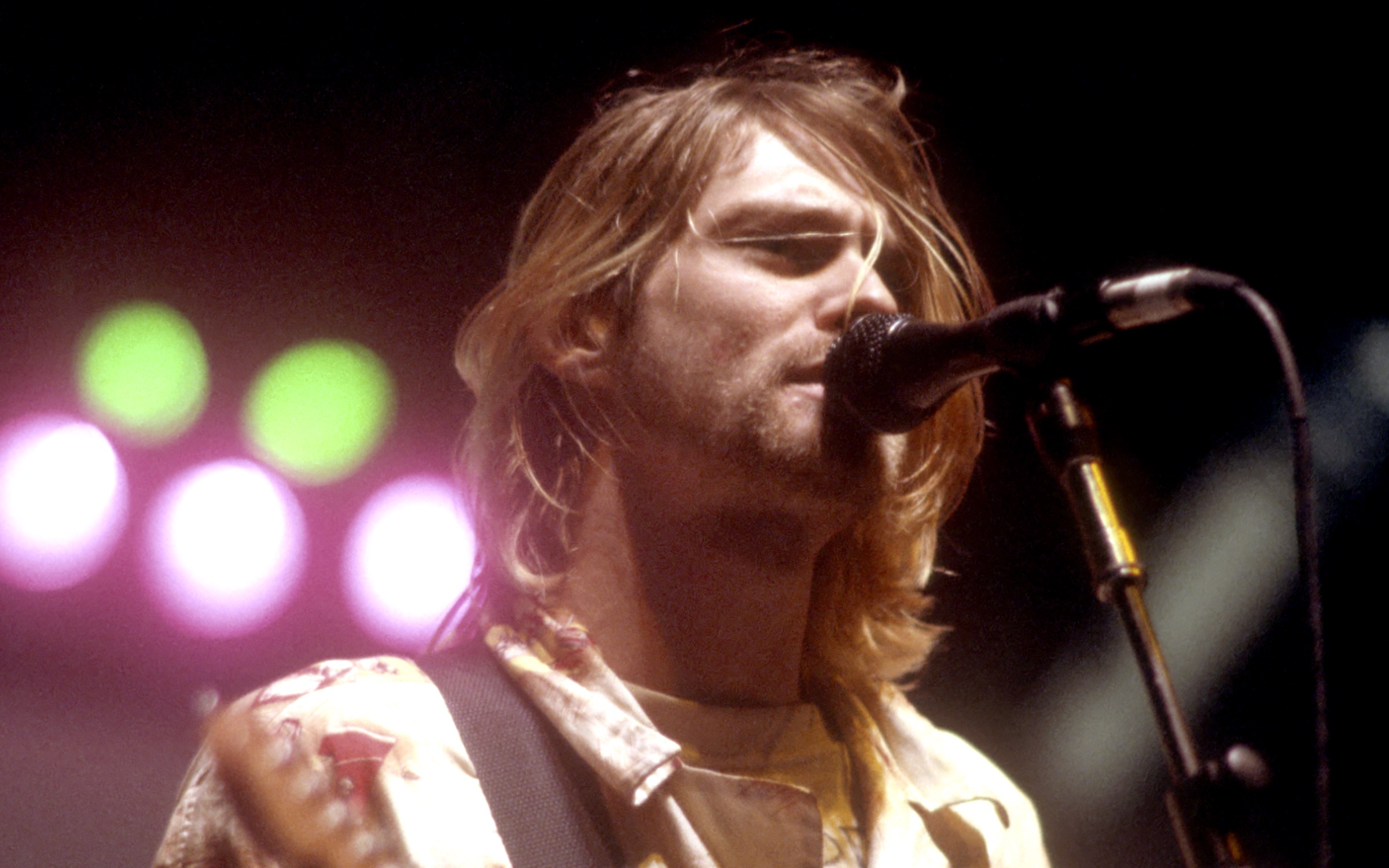

Stories like this cram the musical history books. Kiss were lambasted for writing anthems as nuanced as nursery rhymes – then Alive! perfected their pageantry. Motörhead albums couldn’t crack the coveted UK number one spot until No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith. Bob Marley’s Live! contains the definitive version of his most famous song – ‘No Woman, No Cry’ – and the funerary MTV Unplugged in New York is Nirvana’s unofficial epitaph. So why are they not told anymore?

Photo: Hulton Archive.

Rolling Stone’s list of the 50 greatest live albums contains merely two released in the 21st century – Led Zeppelin’s How the West Was Won and Phish’s New Year’s Eve 1995 – and they were recorded in the 70s and 90s, respectively. Meanwhile, for newer artists, such output represents a commercial downgrade. Live at the Royal Albert Hall was Arctic Monkeys’ first album to not become a UK number one.

Even a cursory glance at any modern megastar’s back-catalogue – Taylor Swift, Ed Sheeran, Imagine Dragons, Maroon 5, Coldplay – will affirm that live releases never out-chart their studio counterparts anymore. Rap heavyweights from Eminem to Drake have never faced the need to release one, full-stop. The live album is dying.

Fact is, the grim reaper’s been stalking the format for decades. In 2021, Classic Rock magazine described Iron Maiden’s 1985 masterpiece Live After Death as “the last great live album of the vinyl era”. The cost of VHS tapes began nose-diving in the mid-1980s, ushering in the age of multimedia ownership. Suddenly, you couldn’t just listen to your favourite artists’ concerts whenever you fancied – you could watch them too.

The dual formats of CD/vinyl and VHS soon divided any live release’s commercial impact in half, split between conventional charts and fledgling video charts. And getting to number five on two separate tables doesn’t look quite as impressive as climbing to the summit of the Official Album Chart, does it?

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives.

It was a navigable speed bump, though. Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged in New York still became a quintessential swansong, while New Year’s Eve 1995 and How the West Was Won functioned as audiovisual time capsules. They were documents of special occasions or mythologised bands that it was impossible to relive in-person at the time of release.

Deeper underground, the record label of Brazilian metal brutes Sepultura put out the acclaimed Under a Pale Grey Sky: an unapproved live recording of the band’s most commercially mighty but now-broken-up lineup. Fellow metal icons Death released Live in L.A. (Death & Raw) and Live in Eindhoven as fundraisers to pay for founder Chuck Schuldiner’s cancer treatments in 2001. There was still money to be made in the live album market – and for dirt-cheap when you cast the cost of recording one gig against weeks in the studio.

Smash-cut to the 2020s and suddenly no form of music makes money. Streaming services charge the consumer £10 per month, as opposed to the £25 per album they’d pay at the shops to buy a one-LP vinyl record. The lack of income is crippling up-and-coming artists, while labels are recouping their losses by writing up “360 deals”: contracts that grant them serious shares of not just the music’s profits, but those of sold merchandise, YouTube revenue and so on.

Plus, most of us don’t listen to full albums anymore, but to themed playlists generated by Spotify and Apple Music. A 2016 study by consumer group Loop found that 31% of people listen to music through playlists, and only 22% through albums. And these playlists almost never feature the live versions of recorded songs. As a result, the number of plays on a classic like No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith – Motörhead’s most popular release in 1981 – are millions behind the figures attached to their studio-recorded albums of the era.

Admittedly, there are dedicated, official playlists for live music. Spotify has one called ‘Legendary Live Performances’, which is almost entirely composed of vintage rockers like Iron Maiden, Metallica and Jimi Hendrix, and boasts more than 100,000 “likes”. Yet the official ‘Rock Classics’ playlist has 11,000,000 likes and zero live songs.

A more modern case study is Belgian post-punks Brutus: their 2019 single ‘War’ has three-million Spotify streams, while the version on 2020’s Live in Ghent album has barely 140,000. Other younger bands – like Black Country, New Road with Live at Bush Hall and Snarky Puppy on Empire Central – had to make their live releases contain all-new material to see the light of day.

Considering labels largely sign bands not to three-or-four-year contracts but to three-or-four-album contracts, you can’t blame the bigwigs for not wasting one of those releases on a live recording that, statistically, next to no one will hear. And you can see why streaming services don’t spotlight live songs, either. If you want to be more fully immersed in the concert experience and do it for free, you’d much sooner head to YouTube.

This platform is where the closest facsimile of the classic live album lives. In the space of one click and a couple keyboard taps, you can skip through any timeless on-stage moments, from Metallica’s legendary Seattle live show to footage of Justin Bieber falling down a hole. It’s a marvellous place.

Black Country, New Road released Live at Bush Hall, an album of entriely new material, earlier this year. Photo: Paul Hudson.

All of those decades-old performances – the kind that How the West Was Won, New Year’s Eve 1995 and MTV Unplugged in New York immortalise – live here. Remember those shows that Dave Grohl played with the Foo Fighters after breaking his leg? They’re here. Countless Depeche Mode tours, musicians test-driving songs before they’re properly released, Kate Bush at the 2012 Olympics – it’s all here, and no form of traditional media can compete with the ease of access and the ease of uploading it all for everyone to see.

There’s certainly nostalgia for the halcyon days of the live album, and it’s doubtlessly deserved. Neither the voice-shredding magnificence of pop or the chest-thumping strength of rock is better than when you’re in the same room as it and you’re swept up among a thousand other fans. It’s where many artists thrive, and the reality that live recordings of that can’t lead to any more Johnny Cash-like victory stories is tragic.

However, that nostalgia cannot beat the sheer simplicity of opening YouTube and watching your favourites play any time, anywhere, at any age. It’s human nature. And you know what: there’s no shame in watching any artist on your screen for free. If you can, though, swing by a gig next time they’re in town. The money they’re not making from their albums anymore needs to come from somewhere if they’re going to keep playing.