In the late 1950s, New York was an epicentre of the nascent pop art movement. Born as a rebellion against traditional art forms, pop art was inspired by consumerist culture and mass media, with pop artists incorporating everything from comic strips to Hollywood films and advertising into their work.

Among its pioneers were Eduardo Paolozzi, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Ed Ruscha, whose artworks challenged the very notion of art and revolutionised the art world.

Around this same time, photographer William John Kennedy was living in NYC. Having established himself as a successful freelance and commercial advertising photographer, he sensed something special about this new wave of artists. He began to document them – a path that would lead him to become one of the chief documentarians of the pop art movement.

Yet curiously, despite his images’ significance, Kennedy is little known in photography. In a new book, William John Kennedy: The Lost Archive, London-based photography consultant Elizabeth Smith brings together these fascinating images from his archive and introduces us to the talented photographer behind the lens.

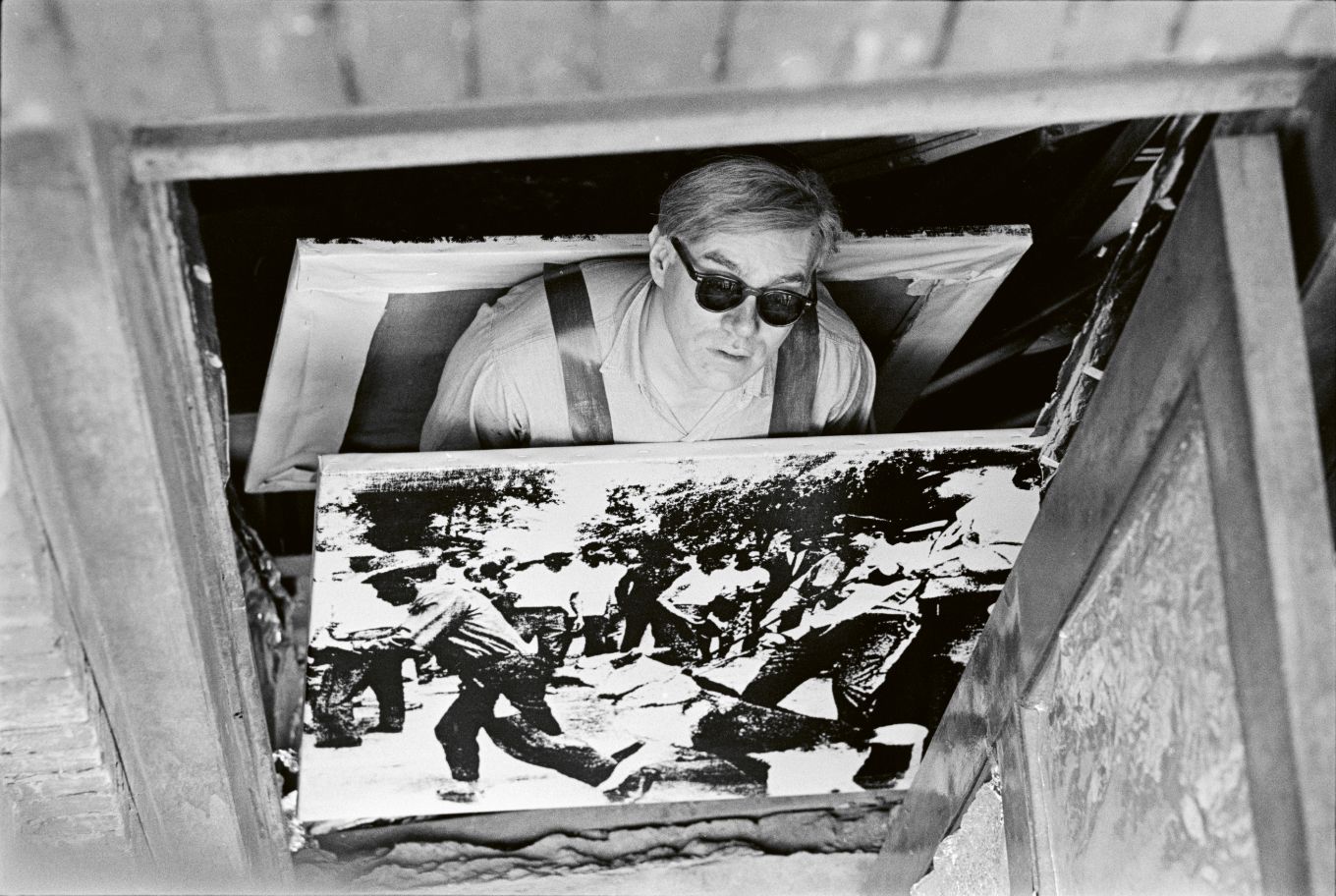

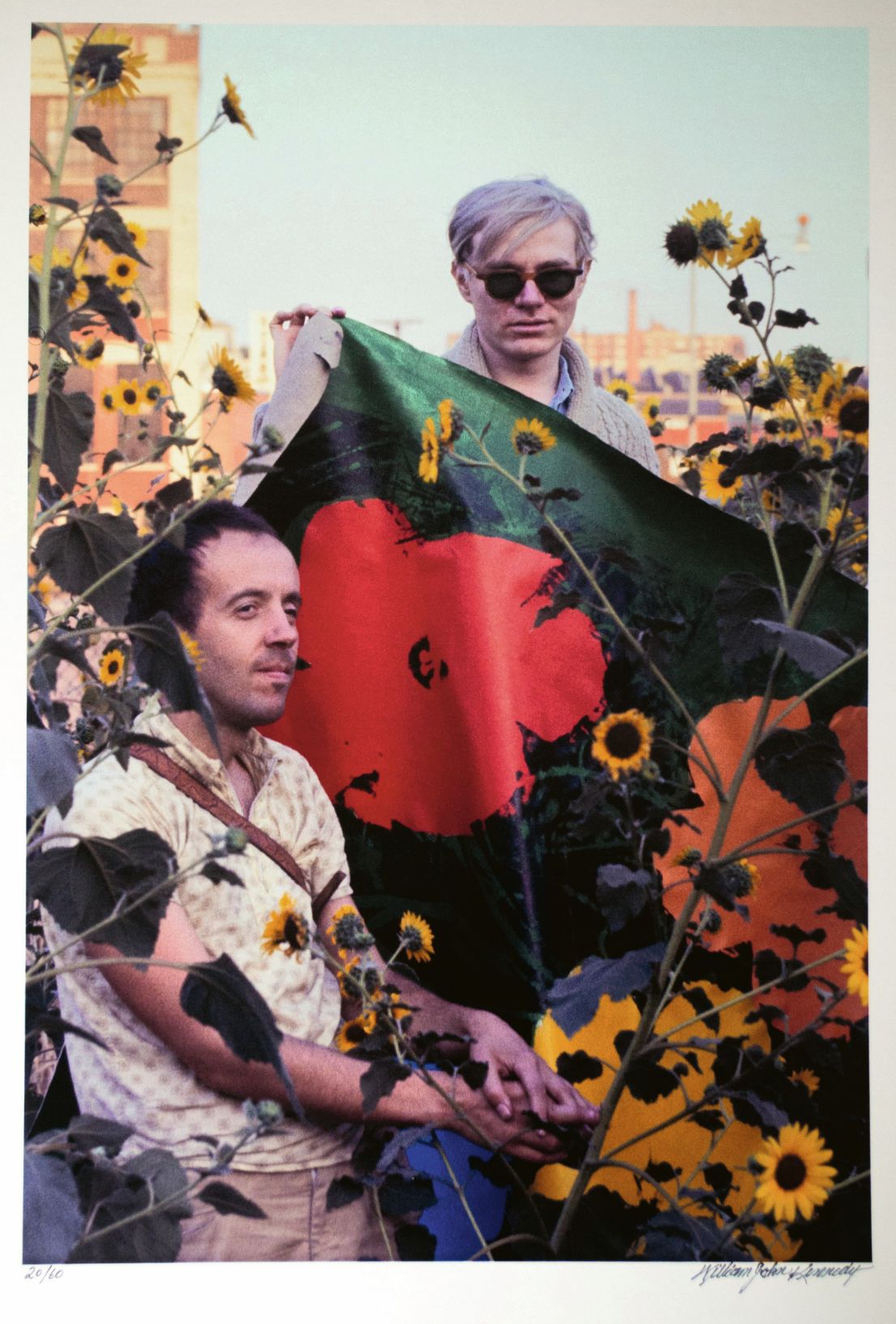

Homage to Warhol’s Birmingham Race Riot

Born in Glen Cove, Long Island, in 1930, Kennedy was adopted by his great aunt and uncle since his parents died when he was a young boy. Kennedy’s great-aunt was passionate about art history and nurtured his love for the arts early on. After studying English and art history, he moved to New York City to study art, design and photography at the Pratt Institute and attend the School of Visual Arts.

When the Korean War broke out, Kennedy enlisted as a paratrooper and received an honourable discharge as a master sergeant in 1953. He then went on to train under the renowned Vogue photographer Clifford Coffin and eventually set up his own studio in New York City.

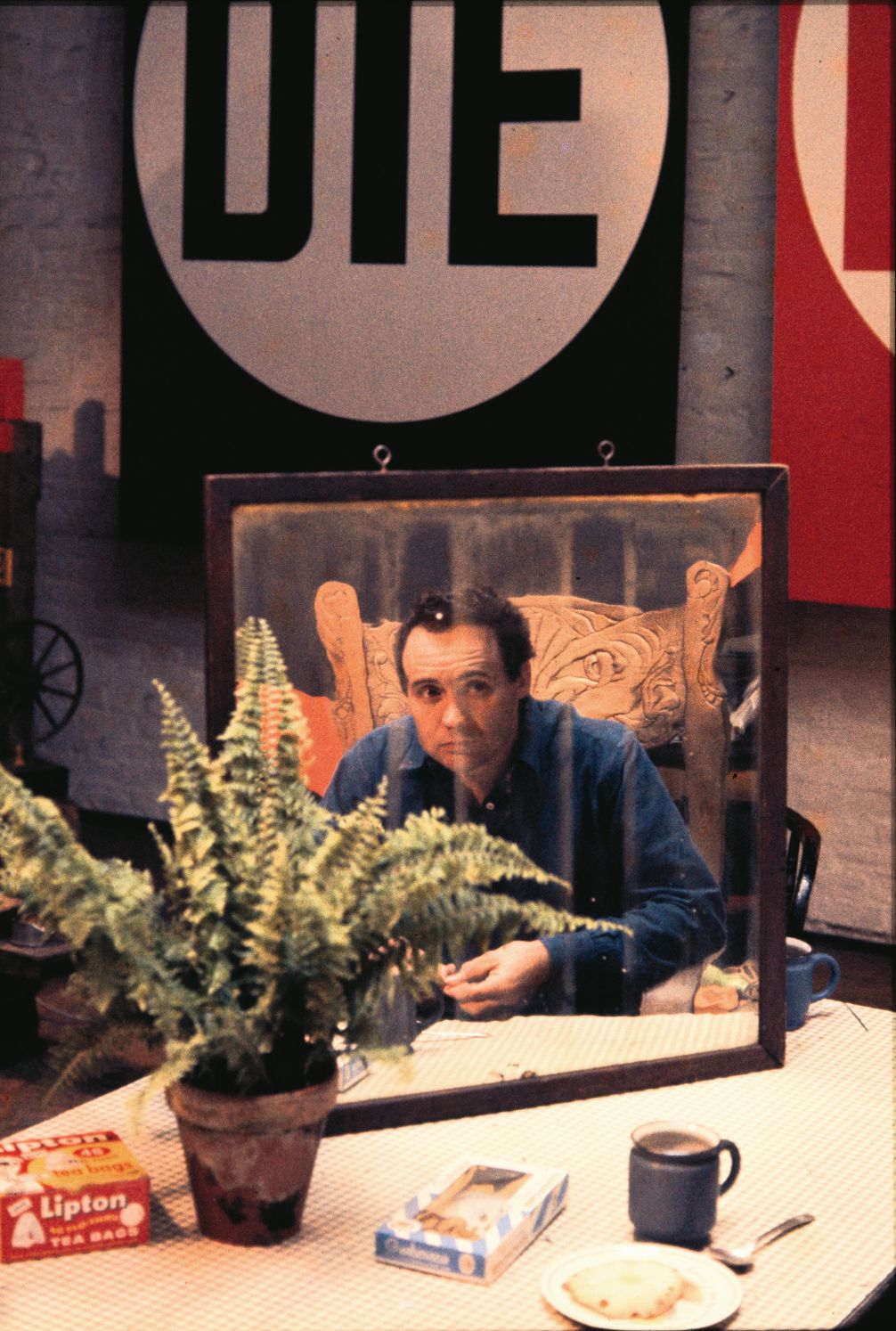

Indiana Smoking in front of Meteors

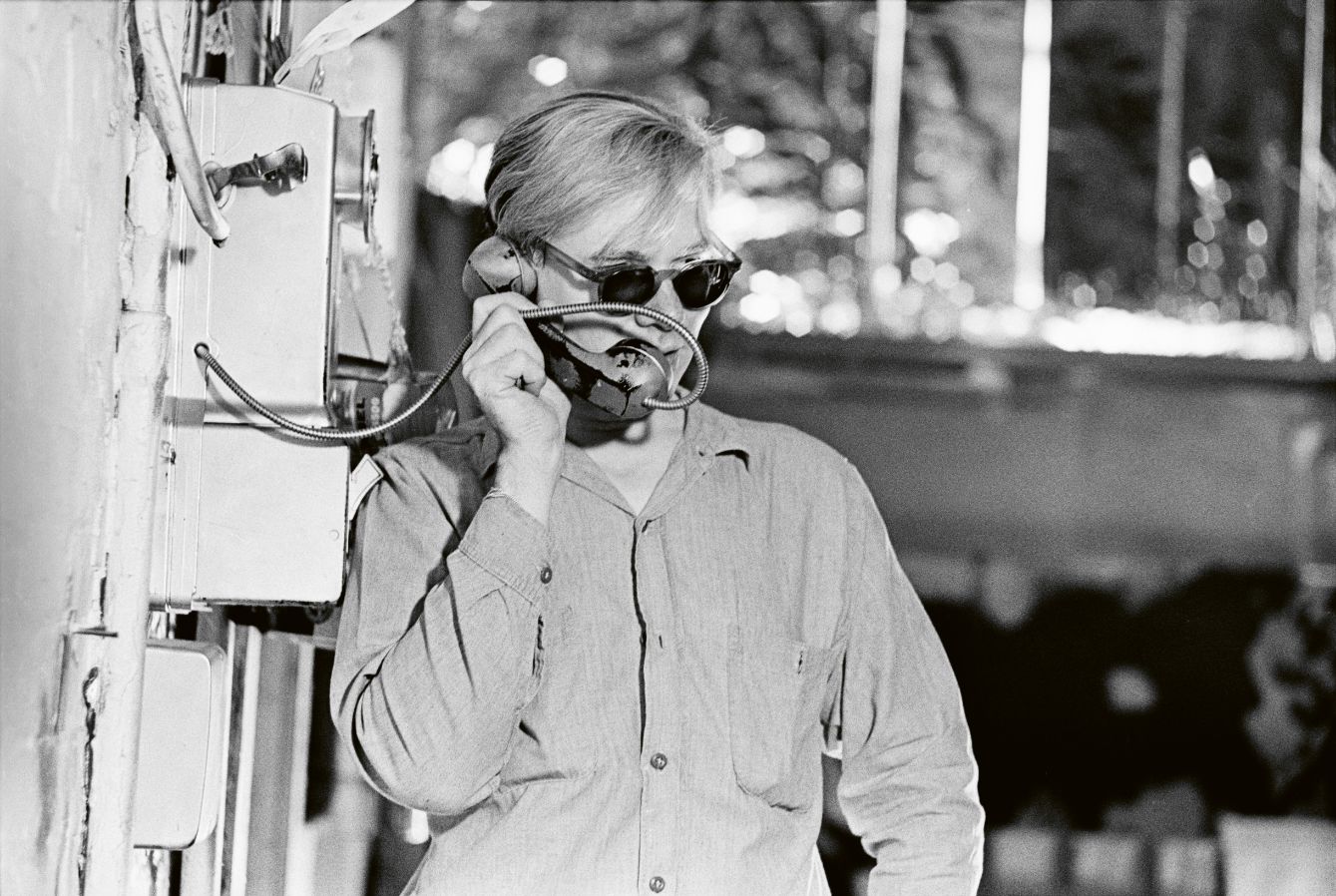

Andy Warhol on the telephone

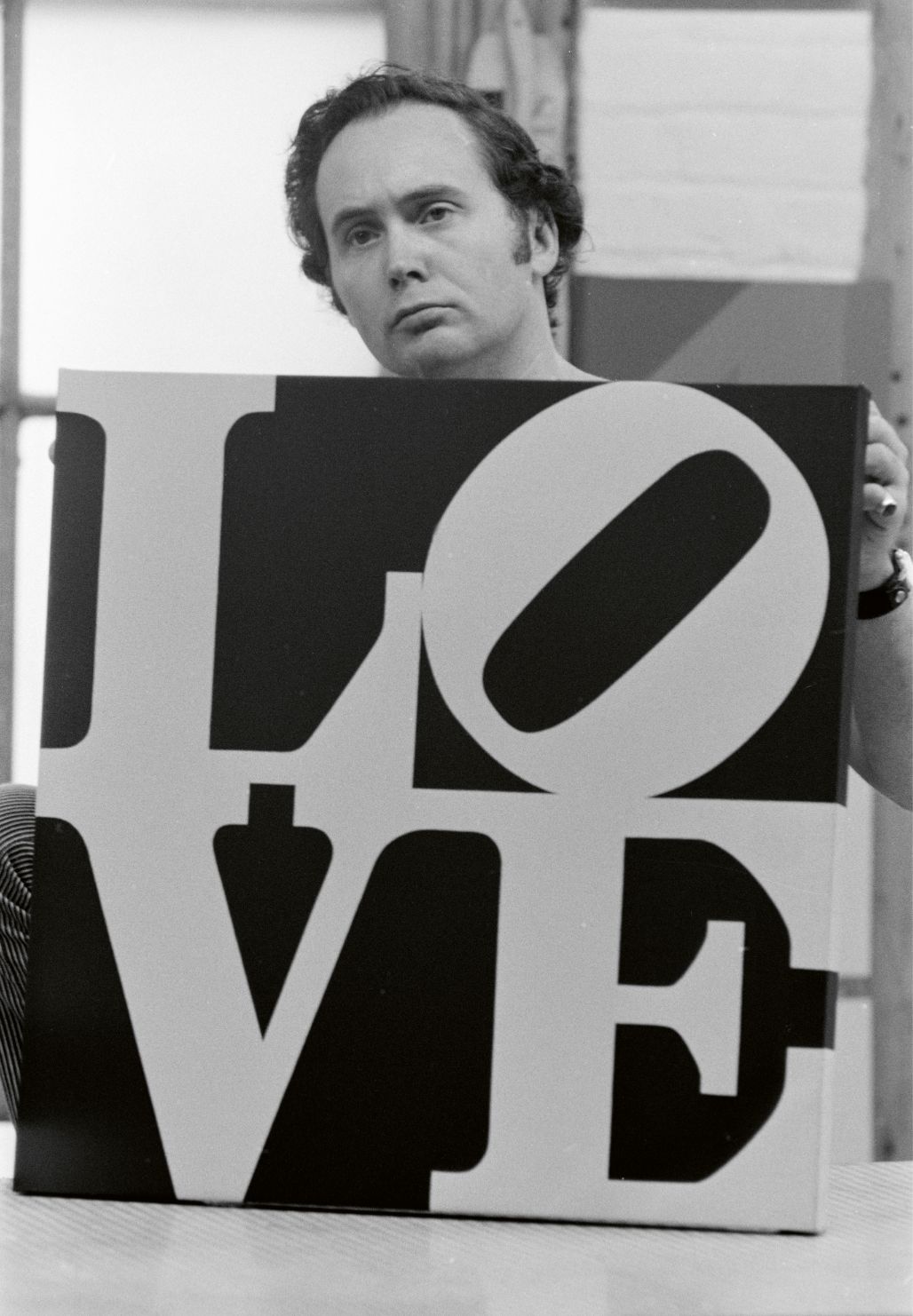

Robert Indiana with LOVE

Kennedy regularly attended open studios and gallery openings to immerse himself in the Manhattan cultural scene. This led him to meet Robert Indiana in 1962, who was then a rising star in the contemporary art world. Indiana created one of the most familiar typographical images of the 1960s, LOVE – where red letters L and O balance atop the V and E – a work which the artist refers to as “probably the best thing that ever happened for me, and the worst thing,” since it quickly became overproduced.

Striking up a friendship, Kennedy visited Indiana and made a series of intimate portraits of him in his studio at Coenties Slip, where the artist was photographed with his artworks, plants and beloved cat.

READ MORE: ‘Andy was a giant’ | Irving Blum, the man who gave Warhol his first show

Indiana introduced Kennedy to Andy Warhol at the opening of Americans 1963 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, a seminal exhibition of which Indiana was a part. Warhol, who was not nearly as well known as Indiana at this point, was not included in the exhibition but was keen to transition from the world of advertising into becoming a fine artist.

Having recently collaborated with Kennedy, Indiana had only good words about his work, describing his approach as “far more synergetic and creative than that of other photographers”. Indeed, he had managed to coax a famously private and reserved Indiana out of his shell for the images and revealed a rare insight into his inner life throughout his career, from his NY studio to Vinalhaven – an island 15 miles away off the coast of Maine, where he eventually retreated. In later years, Kennedy would credit Indiana as the linchpin in his involvement with pop art, for that fateful evening in New York led to another unforeseen collaboration.

Robert Indiana (Copyright: William John Kennedy)

Robert Indiana (Copyright: William John Kennedy)

Robert Indiana (Copyright: William John Kennedy)

When Kennedy first met Warhol in May 1963, he remembered him as somewhat of an enigma. “He was accompanied, as he usually was, by an entourage. Most of the people were talking. Andy stood silently, almost shyly, and slightly apart from the group although obviously a part of it,” Kennedy recalls in the book. Fascinated by Warhol’s presence, which seemed a magnetic blend of contradictions, Kennedy hoped he’d have the opportunity to photograph him.

Shortly after the exhibition launch, Kennedy’s phone rang, and the caller identified himself as Warhol. While he initially thought the call a wind-up, Kennedy soon realised he was mistaken and found himself with an invite to Warhol’s studio – the Factory – to make plans to photograph the artist.

READ MORE: Basquiat and Warhol: Who Exploited Who?

Their first photoshoot took place in early 1964, and like the photos of Indiana, Kennedy was to photograph Warhol with his artworks. This approach would become his signature style through their collaborations. Steered in part by spontaneity, Kennedy could spurn creative ideas on the spot.

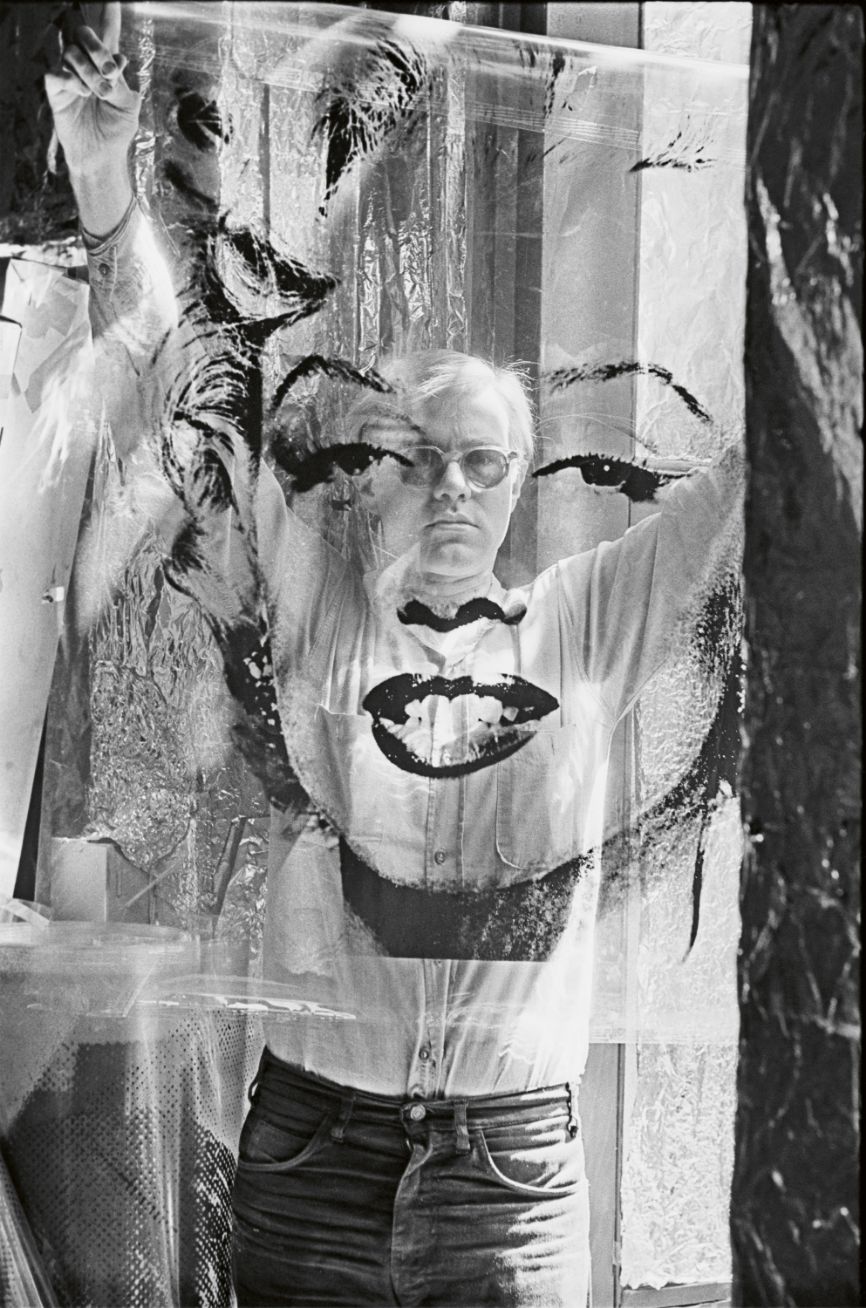

One of the shots to emerge from that initial shoot was the iconic portrait of Warhol standing in the fire exit holding one of his acetates of Marilyn Monroe, which just happened to be lying nearby; after laying eyes on it, Kennedy had asked him to unroll the acetate, not knowing what was on it. The resulting image is a perfect trio of all these elements: Kennedy’s technical expertise, collaborative skill and quick-thinking creativity.

Warhol and Indiana (Copyright: William John Kennedy)

Warhol and Indiana (Copyright: William John Kennedy)

Kennedy returned to the Factory numerous times after that, gradually becoming more familiar with Warhol and those in his orbit, including artist María Sol Escobar (aka Marisol), filmmaker Ron Rice and Isabelle Collin Dufresne (Ultra Violet).

“The Factory welcomed the famous and ordinary in equal amounts,” Kennedy remembers. “It was not unusual to meet rock stars, actors, magazine editors, advertising agency executives, and socialites mingling with the large group of Andy’s underground film stars and his ever-present entourage, who were usually sitting around smoking pot and waiting for Andy to order lunch.”

This intimacy he cultivated with Warhol allowed Kennedy to capture some of his most memorable works. They quickly developed a creative rhythm in which Kennedy would propose ideas, and Warhol was immediately on board, fully trusting Kennedy’s vision. One of those moments was in the summer of 1964.

Driving near the grounds of the World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, Kennedy spotted a large patch of six-foot-tall black-eyed Susans growing in an abandoned field and knew it would be the perfect setting to photograph Warhol’s freshly-painted Flowers series.

He rang him out of the blue, and Warhol uttered three words: Pick me up. This impromptu collaboration led to the iconic set of colour images that Kennedy looks back on as “one of the most beautiful involvements I’ve had with an artist and his work”.

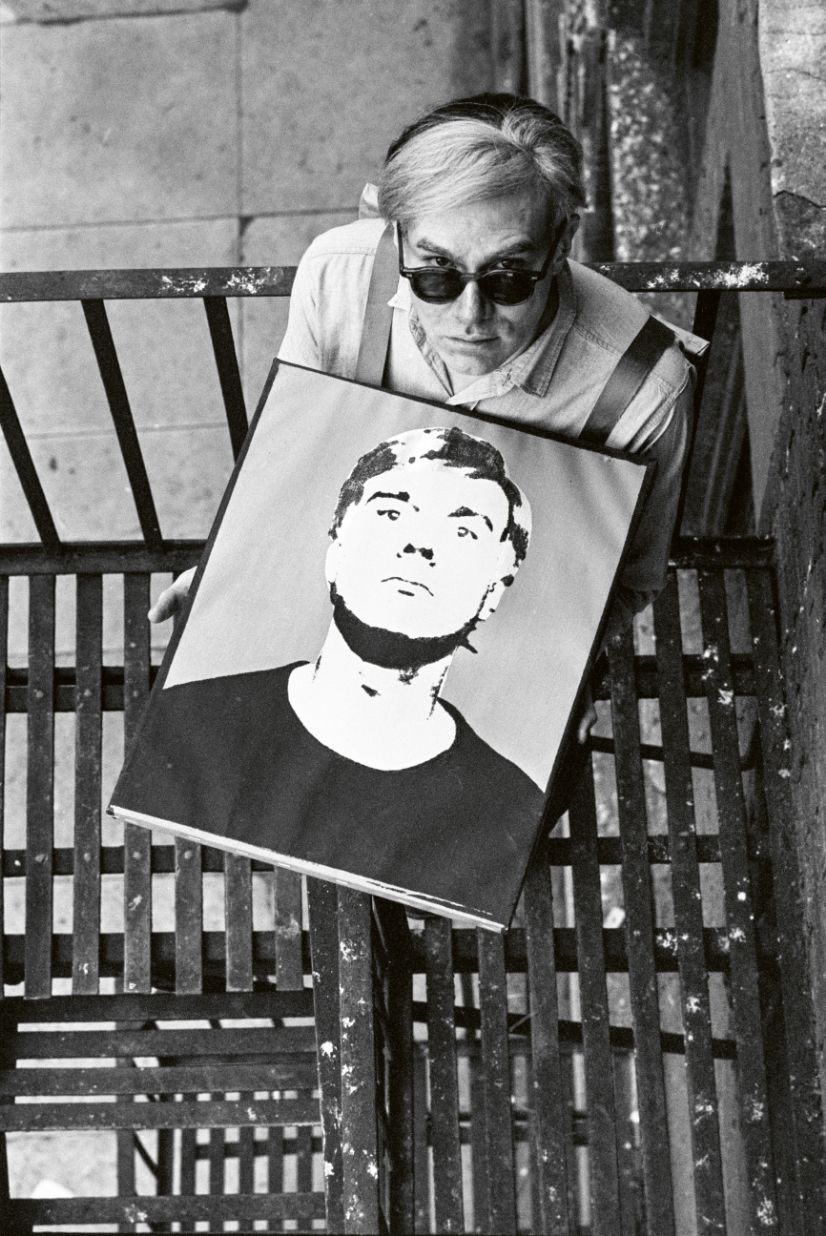

The results were a classic Kennedy-style merging of artist and artwork, as Warhol stands against the makeshift backdrop holding a bouquet. Other photos from that period include Warhol standing on the fire escape of his East 47th Street studio, holding a self-portrait attached to him like a sandwich board – a nod to the artist’s innate ability at self-promotion.

Homage to Warhol’s Marilyn

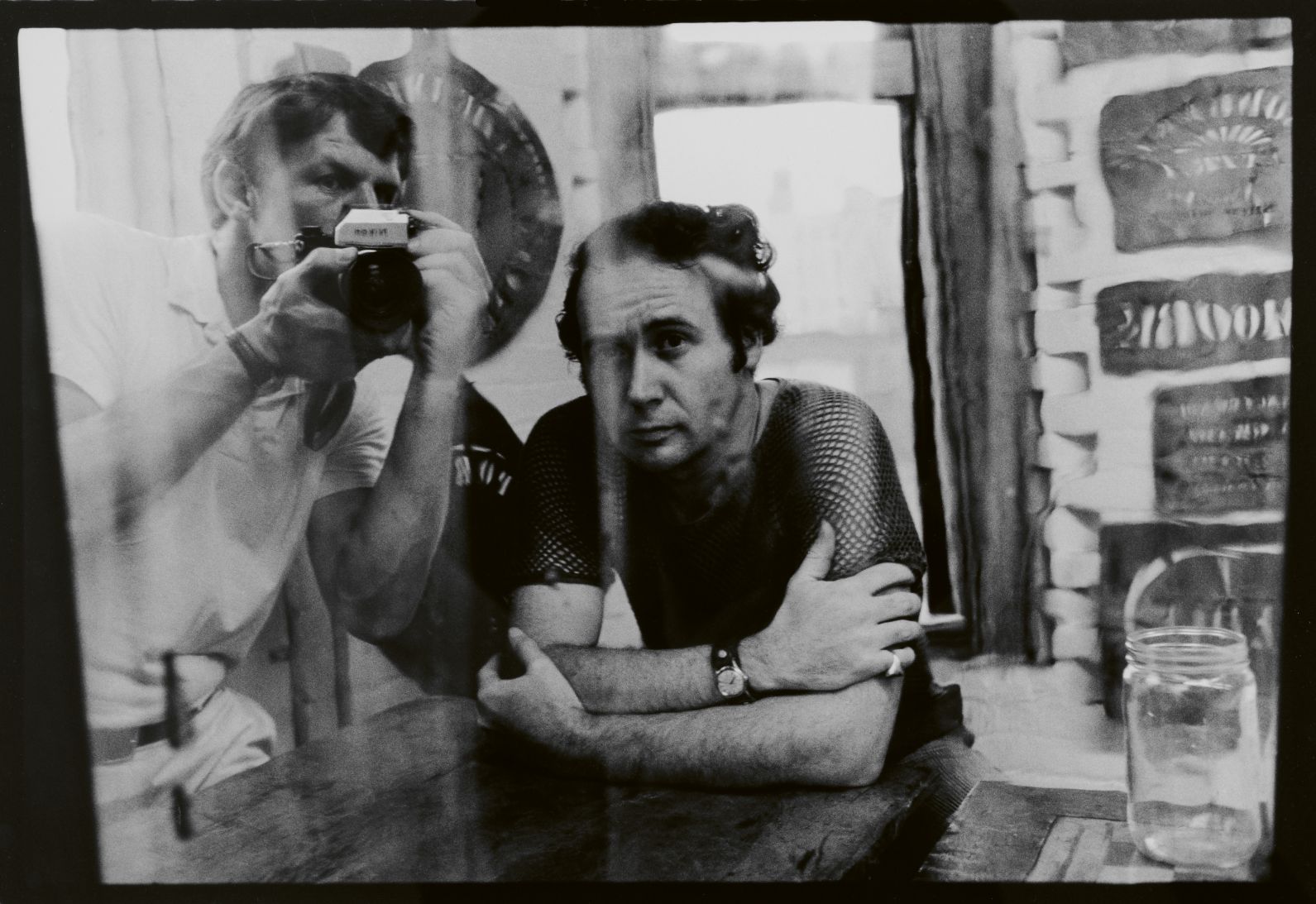

Indiana and WJK in mirror

Homage to Warhol’s Self Portrait

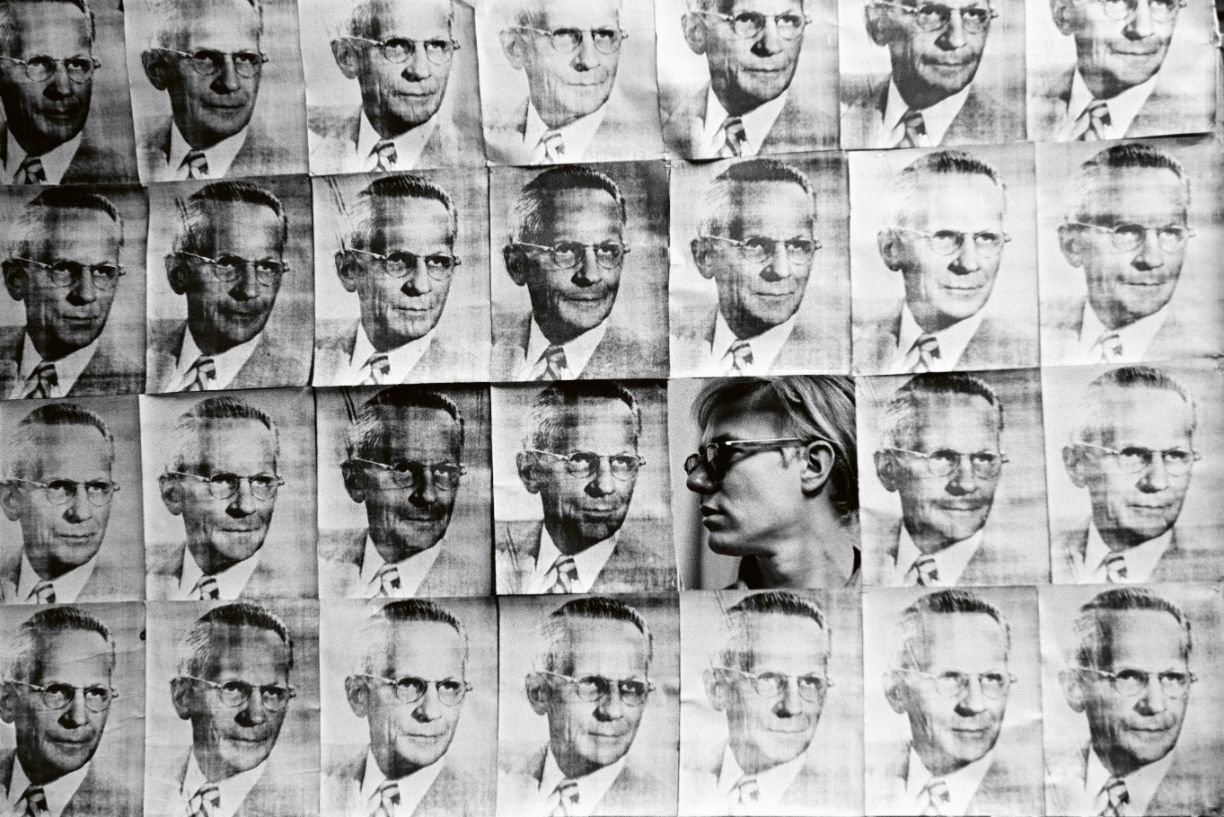

Homage to Warhol’s American Man

As Warhol’s ascent to fame took off, Kennedy became increasingly focused on his own freelance career and eventually drifted from the Factory scene. Shifting his studio to Central Park West – and later, down to Miami in 1984 – he continued to build his professional practice, working for advertising agencies and commercial clients such as Avon, IBM, American Express and Xerox. During this time, Kennedy’s photographs of Indiana and Warhol were put in a box in his closet and forgotten about for the next four decades – until the Kennedys finally rediscovered them in 2008.

When photography consultant Elizabeth Smith was introduced to the work by collector Neil Bookatz, she knew these images had to be shared with the world. “Perhaps [Warhol] remains so noteworthy because he seemed ahead of his time,” she says of the artist’s enduring influence. “His fascination with pop culture, celebrity and wealth resonates with many people today. I think he also remains an enigma. Strangely, since his death, Warhol has become more difficult to understand.

“His public, personal, and private life were completely separate. There was the one Warhol, seemingly shy and reserved but visible as a public figure. Yet privately, he seemed a very different person. We are learning more about his private side, thoughts, relationships – even his spirituality – so I think he is more multi-layered than perhaps originally thought.”

This is where Kennedy’s photos hold such significance as they show Warhol before he became a household name. Despite his own talent and the fame of his images, Kennedy is relatively unknown today. Smith – who believes this is partly due to not having a book published solely devoted to his photography – was keen to bring his remarkable story to light. William John Kennedy: The Lost Archive not only contains the portraits of Warhol and Indiana between late 1962-1964 but also showcases Kennedy’s work too, such as his striking images from the Bowery, at the time, considered Manhattan’s notorious ‘skid row’ as well as his later colour work.

“[Kennedy] took photographs incessantly: fashion shoots, street scenes, portraits. However, that part of his work was sidelined,” Smith says. “It was important that people could hear and see his story from the beginning of his career until the end.

“My takeaway is that Kennedy was multifaceted. He considered himself a fine artist and was also a successful commercial photographer. And he had varied life experiences. He had a profound love for the sea. He was a lifeguard as a teenager and became a deep-water diver and fisherman in his spare time. He travelled as well for his work and pleasure.

“In going through his images, watching the documentary or reading his writings, it seems that Kennedy truly loved being in the moment. The fact that this work remained undiscovered for so many years points to this. He didn’t look back. He was always looking forward. That’s a good lesson.”

William John Kennedy: The Lost Archive: Photographs of Andy Warhol and Robert Indiana are available now at ACC Art Books—images courtesy KIWI Arts Group.