Andy Warhol’s impression on the art world is seemingly ubiquitous. With a new docuseries set to reveal his diaries, and a theatre production currently on, we spoke to the art dealer who gave Warhol his first show: Irving Blum. Blum’s life in the art world, though, stretches far beyond Warhol alone.

History is a contentious concept. Some view it as a long road with everything influencing everything else; others deem historical moments as arising purely in and of themselves.

For Irving Blum, one of Los Angeles’ first successful contemporary art dealers, it’s a combination of the two. A moment of instinct that fully appreciated the birth of a new movement. A critical gaze within the context of a new artistic sensibility that was emerging when he took over a struggling gallery on Los Angeles’ North La Cienega Boulevard in 1958.

That gallery was Ferus Gallery. And the artistic sensibility – of course – was Pop Art.

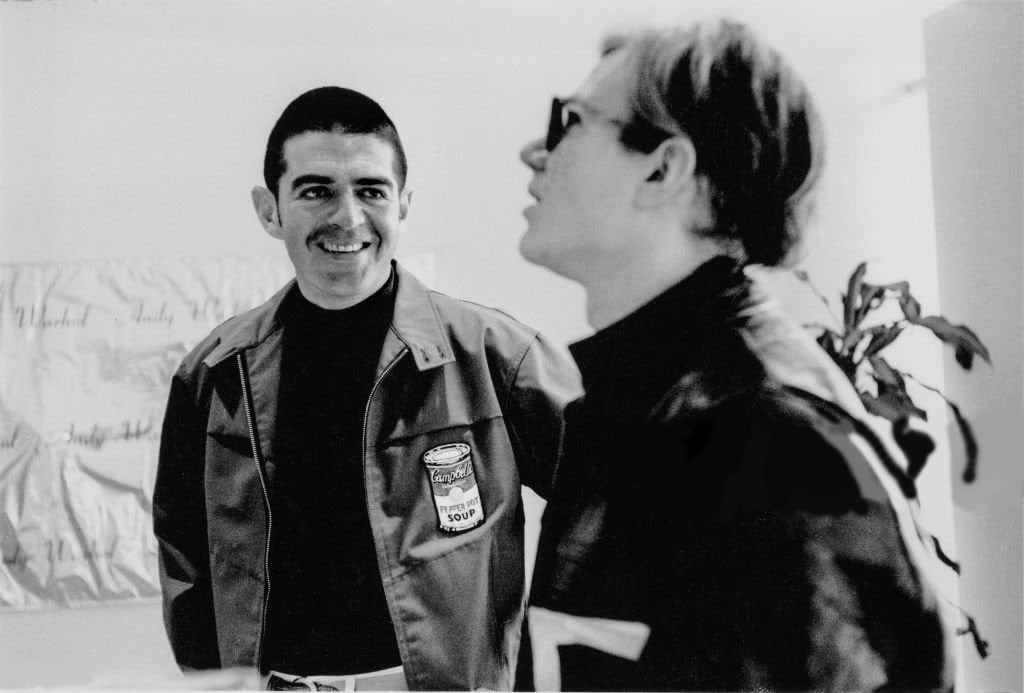

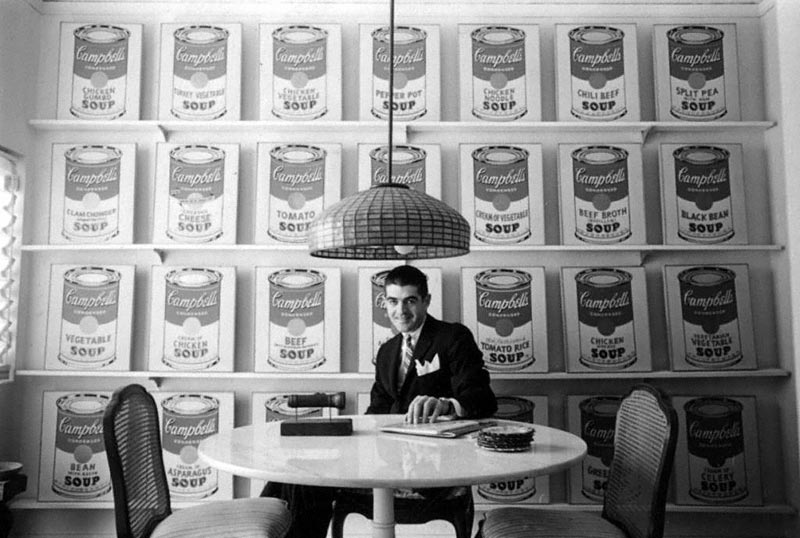

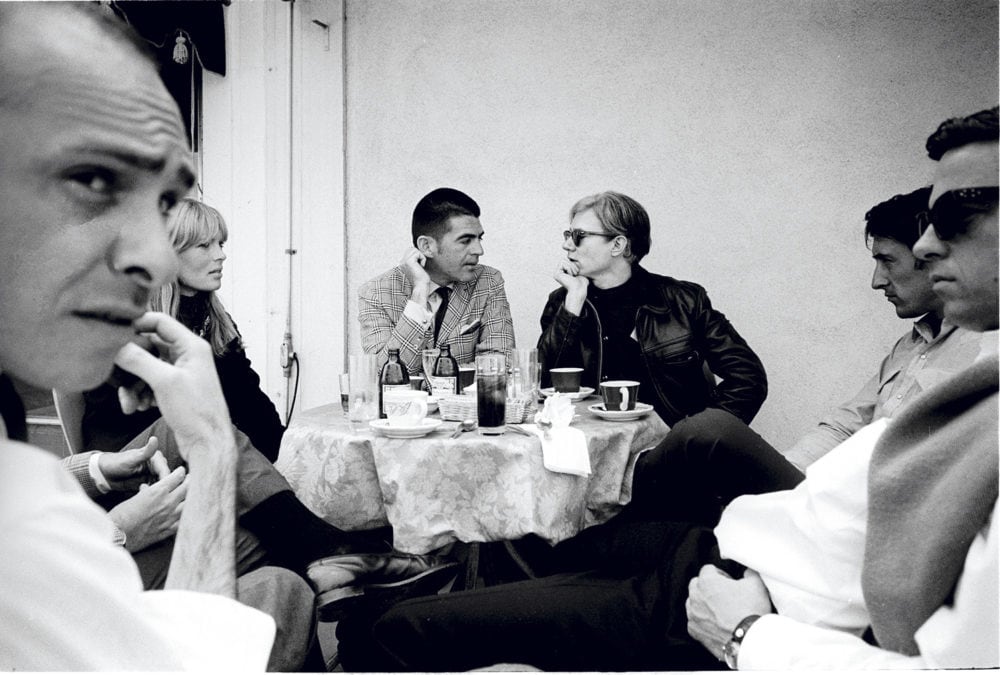

Irving Blum with Andy Warhol’s 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans In 1962. © William Claxton, Courtesy Demont Photo Management, LLC.

For those who don’t know, Irving Blum was the man who brought Pop Art and its leading figure, Andy Warhol, to the West Coast. From there the rest – as they say – is history.

Born in 1930, Irving would go on to join the Air Force before being discharged in 1956, after which he worked for the furniture house Knoll Associates, taking on decorating assignments for corporate companies. A humble occupation it may seem, but Knoll Associates was situated on the corner of 57th Street and Madison Avenue, which was actually quite the artistic hub.

“It seems that most of the New York galleries were a one or two block distance away,” Irving recalls. “So I was able to get to them on my lunch break, and get to know a lot of the dealers, and a number of artists. I was very involved in that world.”

Irving Blum was the man who brought Pop Art and its leading figure, Andy Warhol, to the West Coast

As an early indication of his savvy business mind, Irving saw what was developing in New York’s art world, its post-war buying and selling, as something that could be easily transposed to LA. Not just because it was sunnier there (although that too), but because of its untapped potential compared to an already saturated New York scene.

“I thought I could really compete in Los Angeles,” he explains, “as opposed to doing something in New York, where you had to be funded much more liberally than I was.”

But before Irving immersed himself fully in the LA art scene, once he arrived there in 1957, a slight artistic detour occurred by chance. Through a mutual friend whom he knew from his time in the Air Force, Irving got to know the film director Russ Meyer and helped him write The Immoral Mr. Teas.

“At a certain moment, as he began filming, he said to me, ‘The narrator has the flu, would you come and narrate it? You’ve got a great voice.’ I said, of course. And I did. I narrated the movie.

“At the end of it, he took me to a restaurant. We had a lovely meal together and he said, ‘Irving, I can give you a buyout or a piece of the movie as it progresses.’ I asked what the buyout was. It was $1,500. I took it and that was that.”

Whilst the film would go on to gross “well over a million dollars” (eventually raking in $1.5million) and become Meyer’s first commercially successful film as a director, the $1,500 was what Irving accepted.

Still looking for untapped potential, Irving visited a number of galleries, until landing upon Ferus

In truth, though, this was enough for what Irving craved most: to set up an art gallery in LA. Still looking for untapped potential, Irving visited a number of galleries, until landing upon Ferus Gallery.

“Ferus was the most disreputable in that it was in a rather terrible state, but in a good location. I met the two co-owners of the gallery: Walter Hopps and Ed Kienholz. I spoke with Walter and said I’d like an involvement with the gallery. He said, ‘You’re right on time. Kienholz has decided he wants to go back to his studio, to go back to making art, and he’ll probably sell you his piece of the gallery.’

“I met with Kienholz, we talked, and I told him I’d like to buy his share of the gallery. He said, ‘I’m absolutely prepared to give it up.’ I asked him what sort of money are we talking about? He said $250. I said I can do that, and Walter and I became partners.”

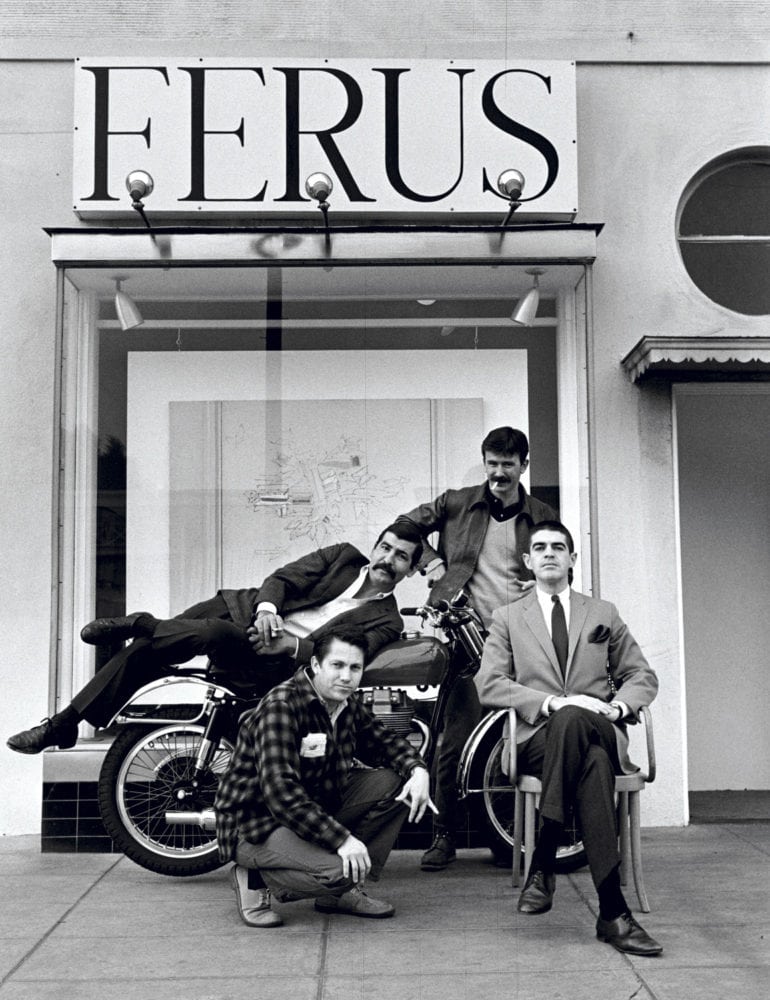

Ed Moses, John Altoon, Billy Al Bengston and Blum in front of Ferus, 1959.

As a co-partner, one of Irving’s first calls was to persuade Walter to move to a better space. As fortuitous as his timing in landing Ferus, a “small but lovely space” also became available across the road; “we were able to take it for very little money then and we went forward that way”.

The move across the road might have been a local one. But Irving’s vision for the gallery was of something a little further afield.

“My only plan was to show the artists on the West Coast – that was really pioneered by Ferus early on, for example in John Altoon and Robert Irwin. I thought I would continue to show these people and, at the same time, bring people in from New York that I knew about.

It evolved very well, but it was rough at the beginning

“There wasn’t that much excitement at the start – there really wasn’t,” Irving admits. “But I persisted. It evolved very well, but it was rough at the beginning.”

It takes a certain fortitude to create a buzz, but Irving was determined to make a success of Ferus Gallery, and asked for the help of three people: Henry Geldzahler, “before he became Henry Geldzahler”; Bill Seitz, who was a curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA); and Dick Bellamy, who was running the Green Gallery at the time.

Rather than be part of a heady elite, cut off from the real artistic movements, “these people went into studios,” Irving explains. “I thought they were really knowledgeable and that they could help me. I went to the three of them said, ‘Can you send me a list of people I should be interested in?’ All three of them did.”

One name appeared on two of those lists. Andy Warhol.

“Andy was on two lists: Bellamy’s list and Geldzahler’s. This was in 1959. So I called [Andy] and asked if I could come and visit. He said yes. I arrived and there were several unfinished cartoons – unfinished – which I thought was really peculiar. There was this music playing: The Ronettes singing ‘Be My Baby’ at peak volume. You could barely talk.

“I was interested in what I saw, but not so terribly interested; I was more interested in him, his curiosity, and his attitude. I liked him. I said, ‘Look, I’m gonna think about these. And we’ll be in touch.’ I left, and that was that.”

I asked why 32? He said, ‘There are 32 varieties and I’m going to do every one’

Almost three years later, in February 1962, Irving would return to New York. One of the first things he did – the unfinished cartoons still on his mind, his artistic instinct still whispering in his ear – was to get in touch with Warhol.

“I went to Lexington Avenue, where he lived in this little house. I walked in and he was in a back room. I walked down a small corridor to get to where he was, and in the corner there were three paintings of Campbell soup cans, and a photograph of Marilyn Monroe torn out of a photography magazine and pinned to the wall, over the soup cans.

“I looked at this little ensemble, walked back and there he was. I said, ‘Hey, three soup cans; why did you do three of them?’ He said, ‘I’m going to do 32.’ I asked why 32? He said, ‘There are 32 varieties and I’m going to do every one.’

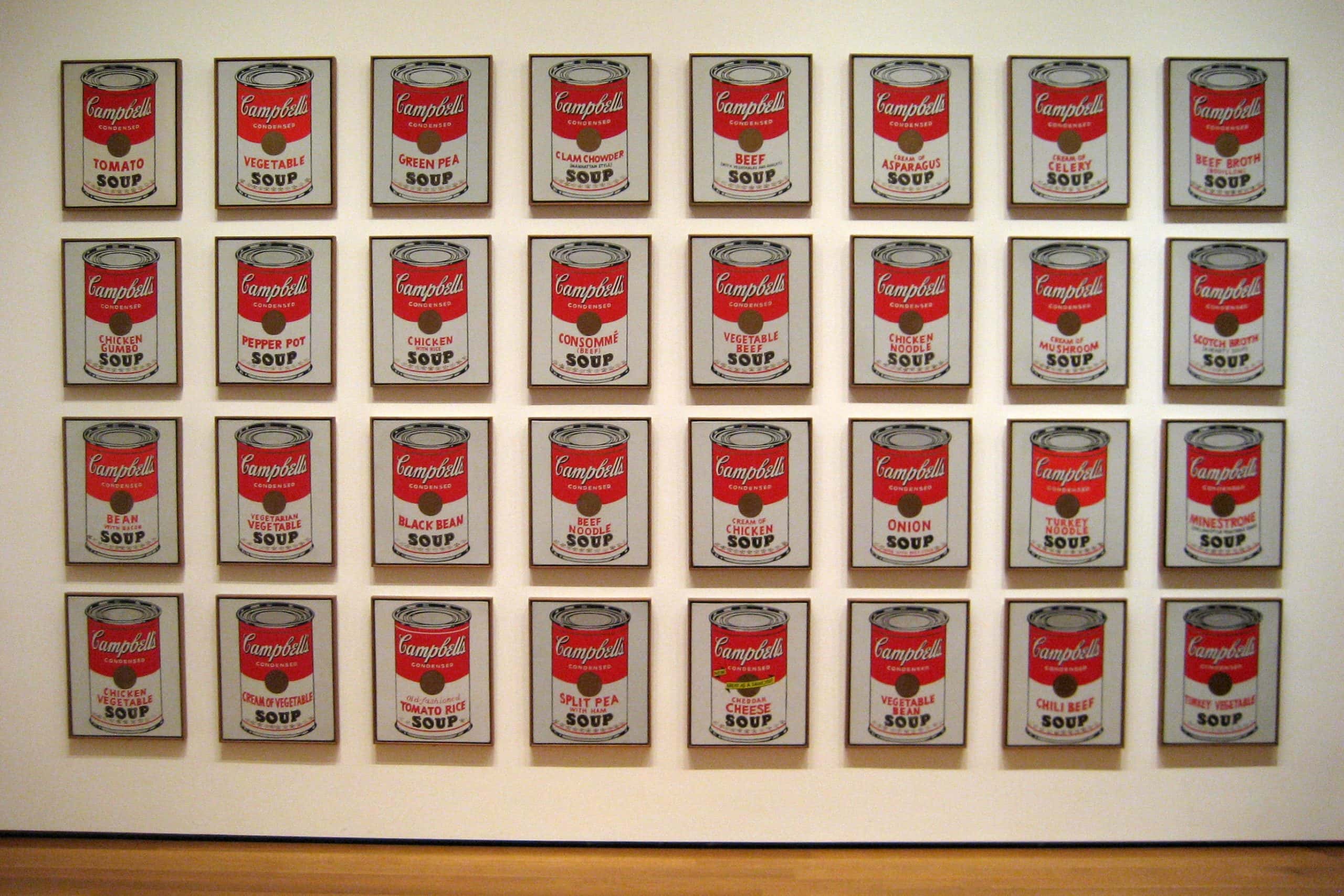

Andy Warhol (American, 1928–1987). Campbell’s Soup Cans (detail). 1962. Synthetic polymer paint on 32 canvases, each 20 x 16″ (50.8 x 40.6 cm).

“So I thought about them. And looked at him. And thought, ‘Do I dare?’ I did. It was a very complicated moment for me. I said to him, ‘Do you have a gallery? Has anyone picked you up?’ He said, ‘No, no gallery, no representation.’ And then I blurted out, ‘What about showing these in California?’ And he thought and thought and thought.”

Instinctive once more, Irving remembered the Marilyn photograph that he’d walked past. “I said to him, ‘Andy, movie stars come into the gallery.’ He said, ‘Let’s do it.’ But it was a lie. Movie stars never came into the gallery. Dennis Hopper came into the gallery; he was the only movie star I had any contact with. But I told Andy we had movie stars. He liked that idea. And that’s how it came about.

“I thought that would engage him; he was rather star conscious. He liked the glamour. And I knew that he did from conversations we had had. So it popped into my mind, and it really worked.”

But it was a lie; movie stars never came into the gallery – but I told Andy we had movie stars

Sure enough, in July 1962, after a tale of Irving’s part-persistence and part-instinctiveness, Ferus became the first commercial gallery to show Andy Warhol, displaying all 32 of his Campbell’s Soup Cans – one, of course, of every variety, from ‘Beef Broth’ to ‘Italian-Style Vegetable Soup’.

Perhaps fed by the growing Pop Art movement’s reflection of everyday items, Irving even sought to treat the paintings like actual cans of soup, standing them all on a shelf as though they were in a real supermarket.

“I stood them on this shelf. I mean, after all,” he jokes, “soup cans were all sold off the shelf.

Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962 Synthetic polymer paint on thirty-two canvases, Each canvas 20 x 16_ (50.8 x 40.6 cm). Andy Warhol, American, 1928-1987.

Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962 Synthetic polymer paint on thirty-two canvases, Each canvas 20 x 16_ (50.8 x 40.6 cm). Andy Warhol, American, 1928-1987.

“And it worked really well. I thought the exhibition was brilliant – of course. But there were a lot of different points of view about it.”

In truth, the exhibition was something of a flop, with only “four or five” of Warhol’s Soup Cans having sold. Once again bringing together that same combination of persistence and instinctiveness (although by this stage you have to ask if it was more bloody-mindedness), Irving sought to capitalise on the limited sales and thought it best to keep the collection together.

“I had the idea of keeping them all together as a unit. And Andy…he didn’t care; I must say he was reasonably enthusiastic, but it wasn’t a problem for him. And so I called the four or five people I sold individual paintings to, including” – incidentally, the one celebrity who did show up – “Dennis [Hopper].

He said, ‘Yeah, I’ll give you a year.’ So I sent him $100 a month for ten months and I was able to secure them

“And I was able to retrieve them and put the 32 paintings together. I called Andy and said, ‘I’ve done it. I’m going to keep the 32 pictures as a group. But, Andy, what sort of money are we talking for this group of pictures?’

“And he thought for a minute and said, ‘$1,000.’ I asked how long he’d give me to pay. He said, ‘How long do you want?’ I said I wanted a year. He said, ‘Yeah, I’ll give you a year.’ So I sent him $100 a month for ten months and I was able to secure them.”

The sum obviously seems remarkably low now. In 2006, for instance, just the single Pepper Pot Soup Can alone sold for $11.8 million (£8.8 million). Oh, how times have changed. Much of course has been written of the Pop Art movement. Through the lens of Irving’s story, who acquired the collection for just $1,000, the amount of money and wealth that has poured into the art world throughout his lifetime is evident.

The very themes the Pop Art movement was rooted in – consumerism, advertising and, thinking back to the Marilyn image Irving spotted on Andy’s wall before it became the pop image that we all know today, celebrity culture – all had the same underlying subtext that was equally shifting the art world: money.

There’s no sugar-coating. Irving has had his successes. Anyone at the start of a market’s boom would have been. But these triumphs were never guaranteed. His acceptance of a buyout for The Immoral Mr. Teas was perhaps an early indication that money was never his sole purpose.

What Irving is far richer in is experience. He recalls tales in a seemingly never-ending thread; anecdotes which weave into yet more anecdotes. Despite speaking on the phone – occasionally distorted by the ongoing storm at the time – you still feel the pull of his colourful stories, which he tells in a matter-of-fact tone; his accent, much like his life, swinging between that of the clipped New Yorker and the laid-back, culture connoisseur from California.

… his accent, much like his life, swinging between that of the clipped New Yorker and the laid-back, culture connoisseur from California

Now 91, Irving still speaks with the energy of a young art dealer, hungry for the next impressive artist or piece to catch his eye. In fact, true to form, I call him just as he’s at Frieze LA. “It’s a beautiful day and I’m at Frieze.”

He doesn’t embellish. He doesn’t need to. In fact, he drops names of key figures in the art world with a tone bordering on nonchalance. The names of dealers such as Ivan Karp and Leo Castelli. The name of artists such as Donald Judd, Roy Lichtenstein (“I stayed with him right through the 60s and 70s and celebrated his accomplishments”), and of course Andy – who yes, he refers to simply by his first name.

He doesn’t labour on these people but brings them up factually to reach the end of his story. That story of course charting the birth and course of the Pop Art movement.

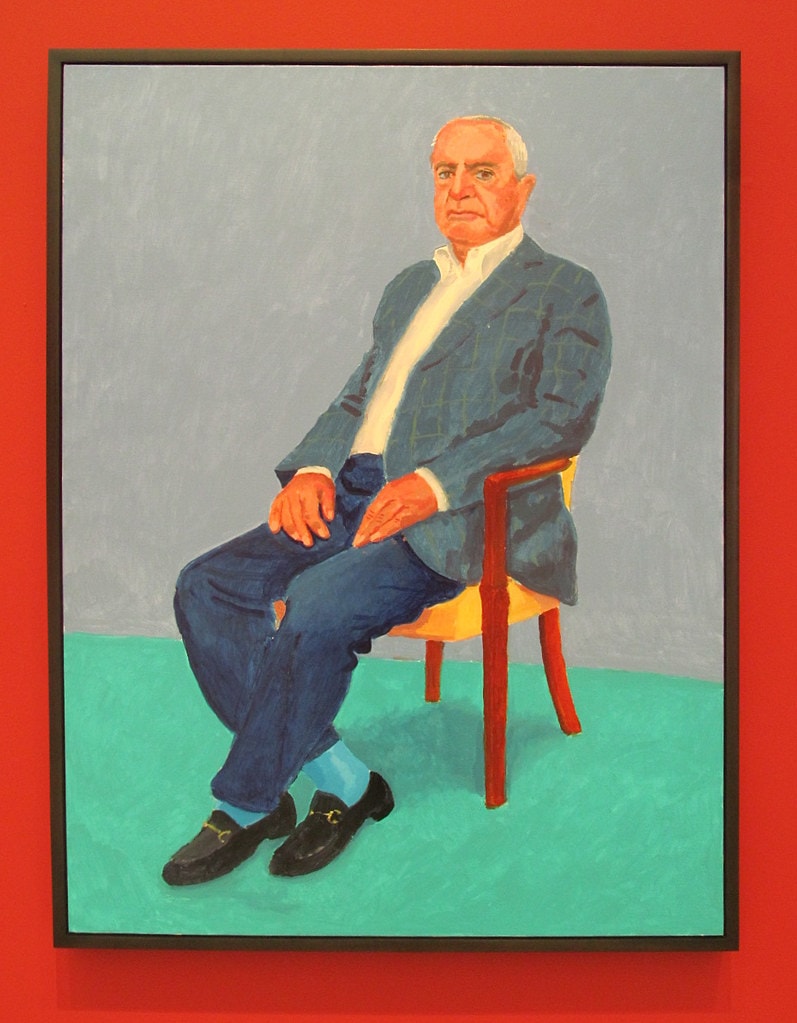

Irving Blum, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, by David Hockney.

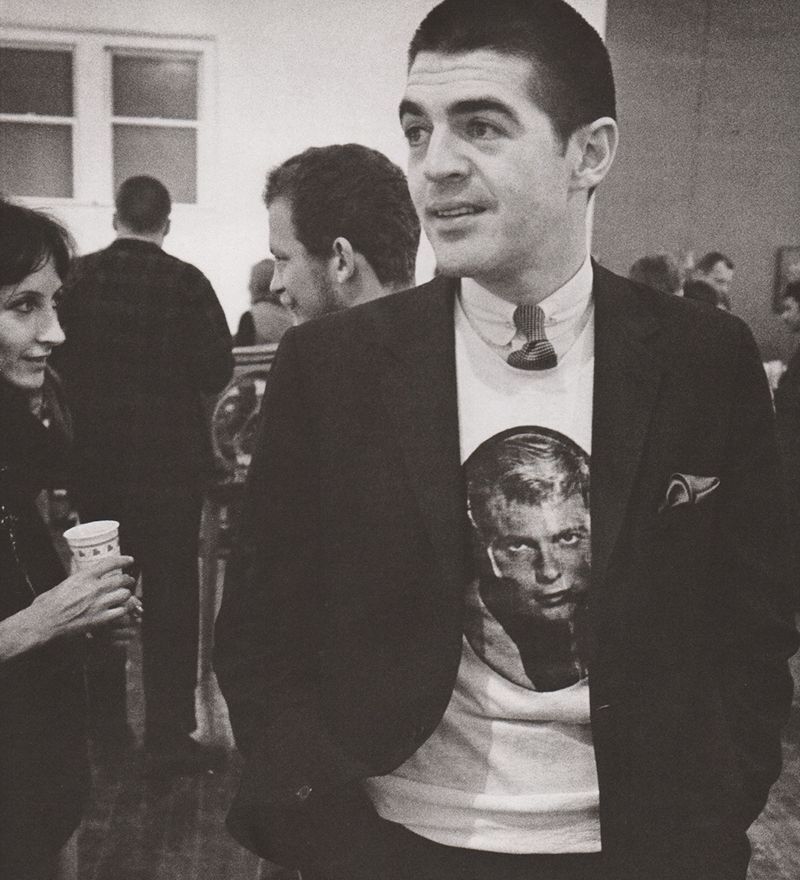

Irving Blum and Grazka Taylor at an event in Los Angeles in 2013.

“I’m very proud,” he now says. “It’s really all about time, isn’t it? You know, you have a point of view, and you stay with it for a moment and then time either bears you out or it doesn’t. For me, it all worked. And I’m very grateful for it. I did what I could to move it along. [Pop] Art had its own life, and it was a remarkable thing to witness.

“I always thought that Andy was a giant. I mean, really, from the beginning, when there wasn’t so much proof. And time has come to bear that out. The guy was absolutely singular, really important.

“I was talking to somebody a few days ago and he said to me, ‘What do you think is the residue of the first time you saw Andy’s work?’ And I said, without even blinking, ‘Picasso and Warhol.’ I believed that then and I believe it now. I think he was a giant. I think time continues to bear that out.”

No doubt it does. Not only is Warhol’s influence so deeply emblazoned in the contemporary art world, but his life too has become a piece of art, constantly being reassessed and re-evaluated in its own right. Take the current play at the Young Vic exploring his relationship with Basquiat, or the forthcoming Netflix docuseries The Andy Warhol Diaries.

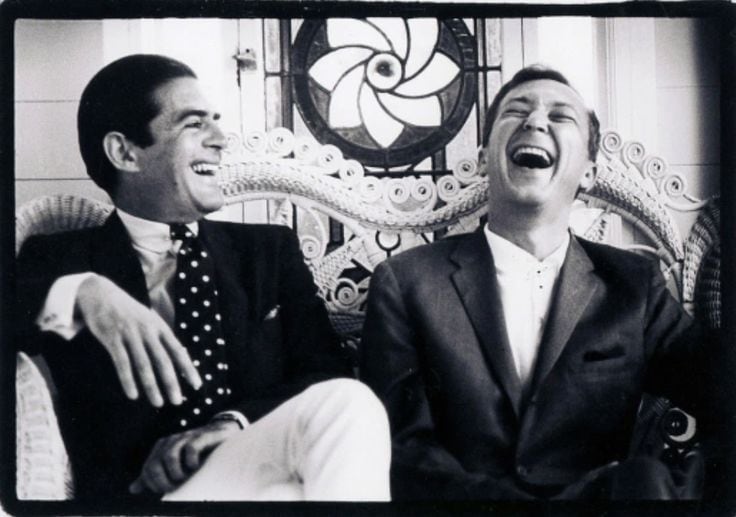

Irving and Jasper Johns.

If anyone embodied the phrase “the idea is not to live forever, it is to create something that will”, it was the man who was credited as saying those words: Warhol himself.

But credit should be extended, too, to the man who persisted in giving Warhol his first show. For he helped shape history too – be it through instinct or the winding road of influences.