Nursing homes are a vulnerable place to be at the best of times. But now more than ever. Care homes have proved coronavirus incubators and sadly account for a staggering share of the death toll in both the UK and the US. It’s time we confronted our biases — both personal and systemic — towards the elderly. Fort Gansevoort’s online Nightshift exhibition is the perfect place to start.

ArrayMichelangelo Lovelace

ML014

At The Intersection of East 79th And Old Cedar

1997

72.25 x 72.25 in

Acrylic on textured canvas

Nightshift brings together 22 drawings spanning from 1993 to 2008. Michelangelo Lovelace’s portraits, drawn from over 30 years experience as a nurse’s aide, bring such character to a space I often think of as characterless. Even the phrase ‘nursing home’ brings back memories of nonenal, high-backed chairs, and institutional hallways — memories I’ve shut away. Perhaps just like how, as a society, we’ve conveniently neglected the elderly.

‘Residents in the Day Room on the Fifth Floor’ (1993) proves a welcome to the community in marker pen. The only figure facing us is, ironically, featureless, emitting authority in a blue power suit on TV. The rest of the room is loosely orientated towards the television set; I say ‘loosely’, because Lovelace brilliantly captures the disjointed drift of chairs and wheelchairs seemingly pointed towards nothing in particular, an angular awkwardness echoed in the sketchily rendered octagonal tables.

Michelangelo Lovelace

ML224

Louise McKenzie

1996

8.5 x 11 in

Ink on paper

A man in the background appears to be asleep, another man to the right of him is scratching his face, a couple to the right again might be talking, but perhaps in murmured tones — you can imagine the television being the loudest thing in the room. Disjointed and subdued the Day Room might seem, but in fact it’s just the opposite: Lovelace brings these disparate figures together with vibrant blues and yellows, hastily hatched net curtains beaming like party streamers.

The exhibition’s real vitality, however, comes from the easy intimacy in Lovelace’s portraits. Though ‘Mrs. Hardwick’ (1993) might be resting her eyes, the pastel pink and green of her pyjama top is dancing through to sunrise. There is serious inquiry in the lines of her face: a hint of agitation in the peaceful folds of her brow, her thin hair tucked tenderly behind her ears. The polka-dot pattern of her favourite chair has been faithfully rendered.

ArrayMichelangelo Lovelace

ML098

4th Floor

1993

23.75 x 18 in

Marker on paper

Michelangelo Lovelace

ML253

James Speed

1996

11 x 8.5 in

Ink on paper

Elsewhere, ’Louise McKenzie’ (1996) gazes at us near cross-eyed, clutching a stuffed animal. Her hair is parted and pulled back in a bun, but loose, frayed hairs seem to skip about the page. With gaunt cheeks and coarse, raised eyebrows, her expression is undecidable. Rather she seems to be scrutinising us, as we observe her. An air of sadness runs up against whimsy, and what we’re left with is the simple dignity of an eye-to-eye exchange.

If I were to describe ‘James Speed’ (1996) — another person with asymmetrical eyes, with heavy lids that look like they’re closing, teeth showing through his open mouth, and midnight stubble coming in — you might get the impression that Lovelace’s portraits are somewhat unflattering. In fact, they are fearlessly honest: with faux-naivety, these works don’t make the pretense of assuming to know their subjects completely; nevertheless, there’s something deeply personal and knowable caught in the energy of the lines.

Michelangelo Lovelace

ML086

Mr. William Angel

1993

23.75 x 18 in

Marker on paper

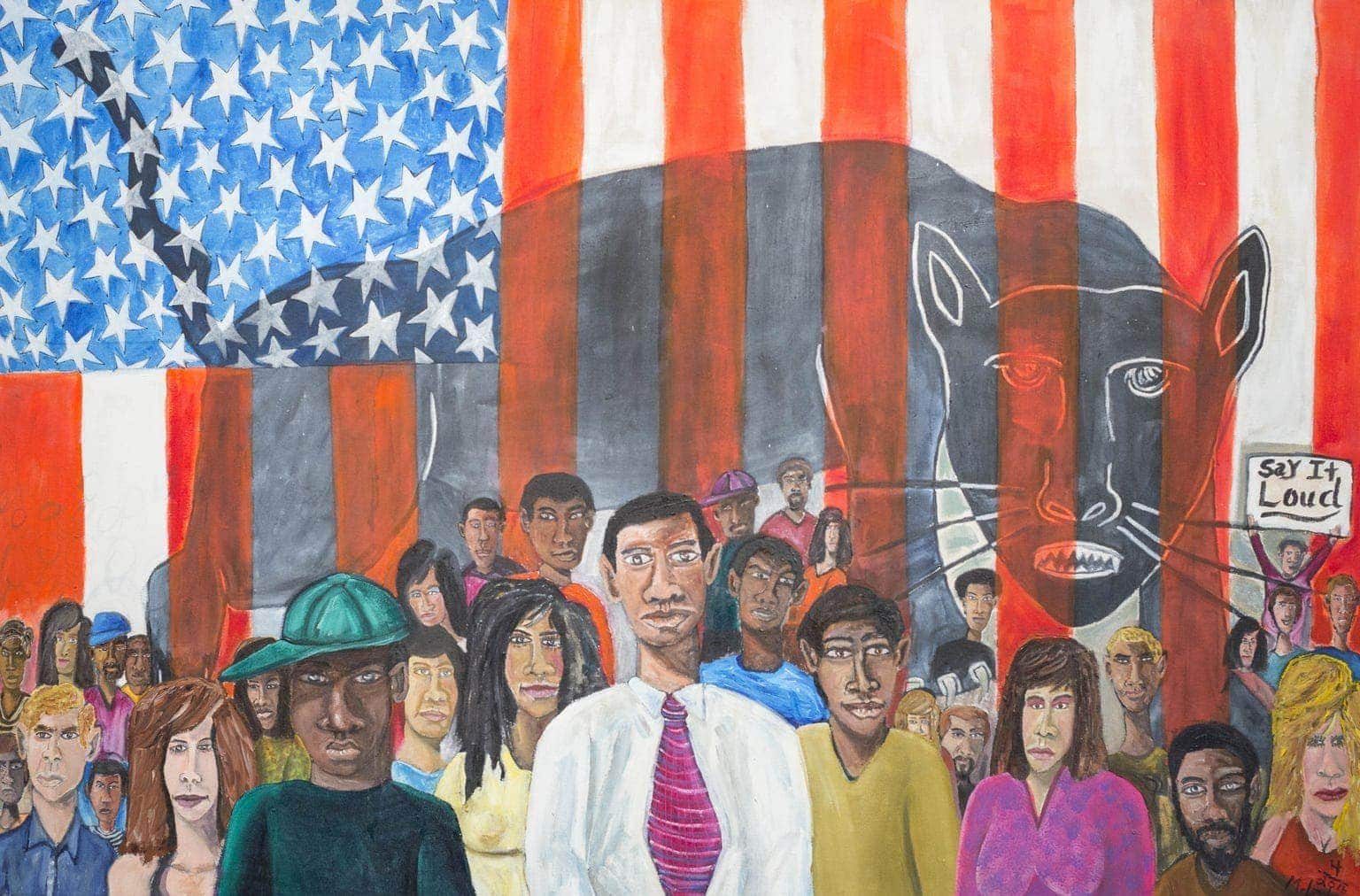

Michelangelo Lovelace is perhaps best known for his bustling toy-town documentations of life in Cleveland. Flat surfaces and two-dimensional plans are brought to bear on issues as deep-rooted and complex as racial injustice, police brutality, and poverty. But in Nightshift, Lovelace trades cycles of violence and vibrancy on inner-city streets for a different kind of community relegated to the margins, largely forgotten by society, shuttered away behind closed doors.

Rather than seeing the elderly as just that — a category — Lovelace urges us to consider individuals with rich inner lives, histories, families, roots, and memories. Lovelace, true to his fashion, puts it powerfully simply: ‘Life is for the living. It’s not just for the young, but it’s for the old too.’