London’s Hunterian Museum, focusing on surgery, will reopen on 16 May after an extensive five-year renovation costing roughly £100 million, The Art Newspaper reports.

It will reopen with a primary exhibit featuring an impressive array of human and animal remains, while also conscious of the ongoing ethical debate in displaying human remains.

The redeveloped museum accommodates the remaining 3,500 items of John Hunter’s original collection of 14,000 human and animal specimens. The original collection fell victim as collateral debris to German Luftwaffe attacks during the Blitzkrieg.

The exhibition considers changing views on displaying organic remains. Previously, samples were mainly for medical professionals and teaching purposes. However, with a broader audience and evolving interests, the exhibit’s role and the museum’s responsibility have also changed.

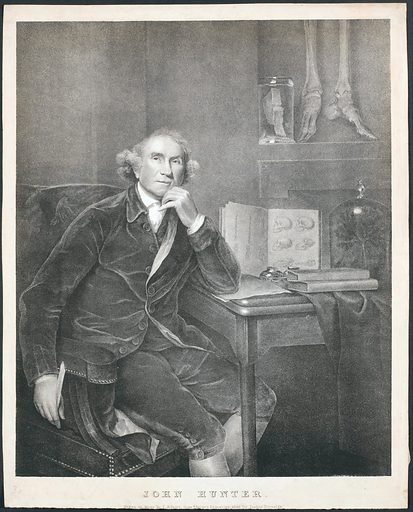

Portrait of John Hunter (1728-1793) surgeon, United Kingdom,. This print of John Hunter (1728-1793), a Scottish surgeon and anatomist, is based on Sir Joshua Reynolds’ painting of 1789.

Below the museum’s surface, with its educational function and glass jars filled with specimens, the exhibition has been redeveloped with a focus on catering to the public’s interest in and awareness of anatomical, medical, and scientifically innovative methods.

An obvious question of ethics and consent surfaces about exhibiting a dead person’s remains. In particular, the case of John Hunter’s ‘Irish Giant’, the preserved skeleton of Charles Byrne, who died in 1783.

In its place will be displayed a portrait by reputable portrait artist Sir Joshua Reynolds, depicting Hunter with the skeleton’s feet edging into the top of the frame.

In light of the vast array of human remains to be exhibited, the Hunterian Museum recognises the need to address sensitivities concerning the display.

View this post on Instagram

The Human Tissue Act 2004 outlines that only human remains older than 100 years are allowed to be kept without permission. Byrne, for example, specifically requested a sea burial (a wish never honoured), but now escapes this unpermitted exhibitionist fate as a skeleton for a more “purposeful” role as a resource for bona fide medical research.

However, there are also questions about the RCS’s ownership of the remains of indigenous peoples, its release for the cremation of the skull of notorious murderer William Corder, and its autopsying of the Belsen concentration camp victims, consisting of Roma Gypsies, Jews and political dissidents.

With some legal guidelines and external pressure mounting from public opinion, the ethical reframing of the Hunterian display remains a task beyond a collection of teeth, bones and surgical tools.