It was still dark outside when an eight-year-old Justin Broadrick was woken up by the police raiding his home. Living in a Birmingham council flat, the future Godflesh frontman watched as his mum and stepdad were hauled outside for questioning by more than half a dozen officers at 7am. Their crime was being members of shock-punks Anti-Social: a band that, in a bid for Sex Pistols-like infamy, had just published a press release looking for someone to behead on-stage for £15,000.

“In ‘78, there were many small-time Malcolm McLarens running around,” Broadrick remembers, now 53 and talking to whynow on the phone from his home near Prestatyn, Wales. “So many managers wanted to take these two-bit punk rock bands and sell them, with the most ridiculous stories, to the press. My mum and stepdad met one in some fucking pub in Birmingham. The publicity stunt backfired and became main Birmingham news.”

45 years later, Broadrick also makes music that’s shocking and transgressive. However, he’s never had to resort to crass stunts (his mum and stepdad were released from custody with a caution, despite finding several volunteers). Godflesh instead earned their notoriety in the late 1980s by taking an instrument as essential as the drums out of the heavy metal equation.

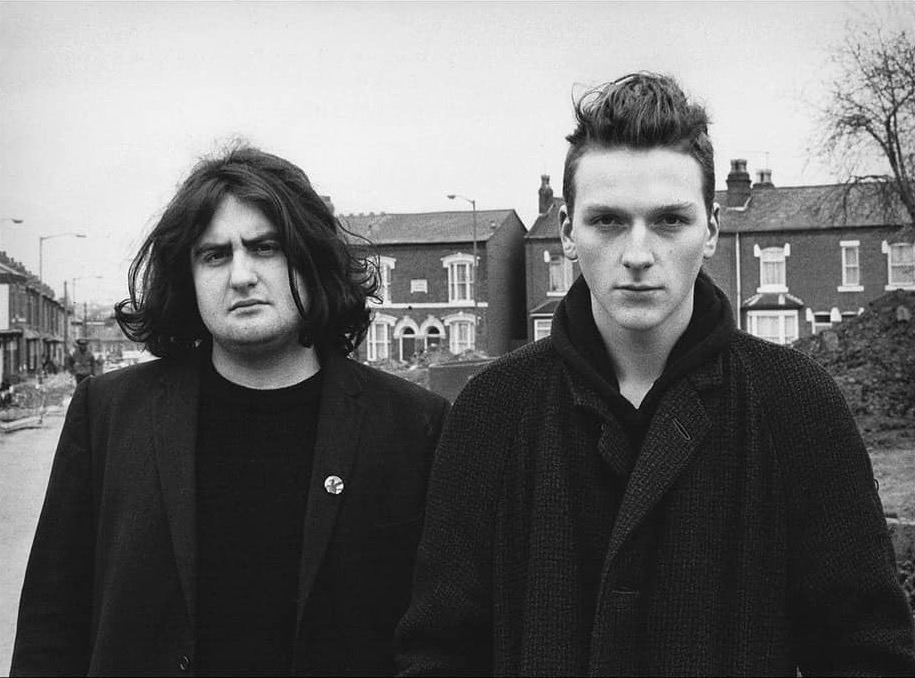

Godflesh, 1988. Photo: Richard Davis.

On their groundbreaking self-titled EP and lauded 1989 debut album Streetcleaner, the duo of Broadrick and bassist Ben “G.C.” Green replaced the kit with a drum machine; the cacophonous beats they programmed were paired with Broadrick’s squealing guitars and incensed roars to, shockingly, make heavy metal the heaviest it had ever been.

Today, such a pioneering yet brutal soundscape means there are only two types of people in this world: people who love Godflesh, and people who’ve never listened to Godflesh. Despite each of their nine studio albums winning critical acclaim, they were never going to sell out stadiums or accrue mass appeal with their music sounding as destructive as it does (their biggest song, 2014’s ‘Shut Me Down’, has barely 1.5 million Spotify streams). Their status among the cultest of the cult is reinforced by the fact the band don’t extensively tour and Broadrick rarely gives interviews.

However, Broadrick and Green are your favourite band’s favourite band. Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett is an outspoken fan, as is Faith No More vocalist Mike Patton. The percussive force of Korn evokes that of Godflesh, Converge were openly inspired by the guitars’ screeching racket, and Rammstein, Fear Factory and Nine Inch Nails later found stardom with similarly mechanical-sounding rock and metal. Godflesh aren’t the most commercially dominant “industrial metal” act, but no one else in the subgenre stretches back as far – nor has displayed the talent to make such heavy music without a drummer in their ranks.

For Broadrick, the secret to revolutionising the heavy metal soundscape lived in hip-hop. “I have one of those early compilations by [British dance music label] StreetSounds,” he says, “where most of the tracks just sounded like a drum machine and a rapper. I was like, ‘Fuck! This is just amazing!’ When that sound exploded, the first thing to really hit me was Run-D.M.C’s [1985 single] ‘King of Rock’ on The Old Grey Whistle Test. It felt so fresh hearing metal guitars with a big, chunky hip hop beat.”

Courtesy of Justin K. Broadrick.

By his own admission, Broadrick isn’t much of a metalhead. As a kid, he overheard his mum and stepdad playing Killing Joke, The Stranglers and Lou Reed’s noise album Metal Machine Music. Then, after going to bed, he listened to whatever oddball music John Peel broadcast on his radio show. In the mid-to-late ‘80s he became smitten with Public Enemy and Eric B & Rakim. So, while Godflesh’s digitised edge came from hip-hop and dance music, the band’s heavy metal intensity didn’t stem from loving Judas Priest or Iron Maiden. Instead, it’s rooted in Broadrick’s own childhood trauma.

“Godflesh is an immersion in what terrifies me,” the frontman explains. “It’s me trying to communicate what I was exposed to as a kid: being so hypersensitive, being so uncomfortable, consistently. I’ve carried it my whole life.”

Broadrick describes his upbringing as “carnage”. After being born in Birmingham to two young parents, he was “about a year and a half” old when his dad left the family. “He was a heroin addict,” the musician remembers, “and not a small-time junkie.” Father and son didn’t meet again until twenty years later.

While growing up in that Birmingham council flat, being raided by the police was just one episode of anarchy. Broadrick describes his mum back then as “an alcoholic and drug-taking lunatic”. He remembers, aged 11, getting high off the second-hand weed smoke lingering in the flat. Wild punk-rock parties frequently raged until 5am while he was at home, made even more overwhelming and damaging by the fact that, as he found out last year, he’s autistic.

Godflesh, 1988. Ben “G.C.” Green and Justin Broadrick (L-R). Photo: Richard Davis.

“I’ve got lifelong PTSD because I should have been cared for as an autistic child with hypersensitivity,” he says. “A child psychologist told me, ‘You were exposed to an extreme lifestyle when you should have been wrapped in cotton wool. You were exposed to carnage and it’s tantamount to child abuse.’”

His school’s misunderstanding of mental health confounded that traumatic upbringing. “I was taken out of school during my first year of junior school and the teachers called my mother in. They were like, ‘Your son is exhibiting quite “special” behaviour.’ All my mum thought I was was pretty fucking weak, as council estate people often did back then.”

Because of his autism and trauma, Broadrick says today, “I’m absolutely crushed by existence. I’m not born for this world; it’s too much for me.” He finds social situations stressful, a major contributing factor to why he rarely does press. “Tonight, it will take me hours to recover from this,” he admits.

Yet, when he does talk, Broadrick is an incredibly verbose and affable speaker. Our interview is almost 80 minutes long, none of his answers leaving anything unexplored. “When I was getting my diagnosis at the Autism Society, they said, ‘Many autistic people are like you: you can’t stop them [talking]!’,” he laughs. “‘You’re constantly searching to be comfortable because humans basically make you feel uncomfortable.’”

Photo: Kim Sølve.

As a result, live performances are an anxiety-triggering prospect for Broadrick. He admits: “For me to perform, I cannot think of the audience as living beings. It’s a painful performance and I can’t communicate with the audience.” Anyone who’s seen Godflesh live will know the frontman never talks between songs – he only ever snarls on top of the band’s pulverising metal.

Broadrick used to cope through alcohol. He recalls once needing to be dragged onto a plane to fly because he was so drunk, before his mental health reached its nadir in 2002. Burnt-out and unable to face the prospect of an impending US tour, the musician suffered a breakdown, cancelled all Godflesh plans and dissolved the band for seven years. During the early 2000s, however, he quit his heavy drinking and dedicated himself to the more atmospheric solo project Jesu.

Today, Broadrick calls music the only job he’s ever had, his therapy. He met Green aged 14 (the pair lived on the same council estate) and soon joined his post-punk band Fall of Because. At 15, he “walked out of his first exam and never went back to school”. He then joined grindcore idols Napalm Death and unleashed all of his aggression at lightspeed on the first half of their debut album Scum: another cult classic among punks and metalheads.

Broadrick started Godflesh with Green as an 18-year-old in 1988, writing songs out of riffs he planned to use during a short stint in industrial band Head of David. “I was like, ‘I want to take these demos and start a new band’ – simple as that,” he remembers. “But we needed a £500 drum machine and we were both on the dole with no money. Ben talked his mum into getting a bank loan, and we went and bought a drum machine that we’d researched.”

Photo: Kim Sølve.

The 1988 Godflesh EP was a clear conduit for Broadrick’s anger and trauma. After a glitching electronic beat opens ‘Avalanche Master Song’, the frontman roars over metal guitars: ‘I could stand the pain for long enough / But the taste is just too bitter.’ Even the claustrophobic, hip-hop- inspired percussion was manipulated to evoke the pummelling sound of Birmingham factories, which deeply impacted Broadrick growing up.

“Birmingham, at that time, was the Detroit of fucking England,” he says, “and I immediately connected with, and was extremely sensitive to, that environment. At the council estate we lived on, at night you could hear factories. In summer, with the windows open, you could smell factories and hear the grinding of sounds. Through my autism, trying to communicate this to fellow kids would be like I was speaking an alien language. It wasn’t until I met older kids who were into music that I could communicate how I perceive that environment.”

After Godflesh got Broadrick off of benefits “relatively quickly”, the musician moved out of Birmingham in the 1990s. Now up in the remote north of Wales, he’s happily isolated with his partner, son and dog, and sounds incredibly satisfied. “We have a property on large grounds with views of the sea,” he says. “I can go walk the dog and not see a single human being, which is fucking amazing.”

The sound of the midlands’ industrial clamour remains key to Godflesh, though. Their new album, aptly titled Purge, is still layering screams and riffs atop drum machine beats. If anything, its sounds seem more allegiant to dance music than those of Godflesh’s origin – especially the drum-and-bass pulses that drive ‘Land Lord’ – but Broadrick’s under no illusion of it changing their underground pioneer status. According to him, the band are still as baffling to the mainstream as they were in 1988.

“People still find Godflesh subversive,” Broadrick says. “There are still people who can’t believe that we use the drum machine as an aesthetic choice. We take from techno, drum-and-bass and early hip-hop, and we abuse those machines.”

For channelling his trauma, eclectic taste and childhood surroundings into Godflesh, Broadrick has created the ugliest of boundary-smashing music. Even thirty-plus years later, no band has outdone the aggression of the drum machine-driven nastiness that he and Green deal in. So, Broadrick wants his legacy to be that of an “innovator”.

“I want to be remembered the way that classic bands from post-punk are remembered,” he says. “I’m proud that this band is seen as some sort of pivotal part of heavy metal. The irony is that we don’t sell-out arenas or sell records. Godflesh’s legacy is huge, but we are a small fucking band.”

Purge is out on 9 June via Avalanche.

Godflesh will be playing Birmingham’s Supersonic Festival, 1–3 September – see here for more information and to purchase tickets.