When you smash a statue or scribble on a wall, are you just breaking something old – or, could you be making something new? If we’re taking meaning as our raw material, then defacement is nothing less than transformative.

Maybe that’s for the best, because it seems we can’t help ourselves.

Demolition of Cheapside Cross

Starting small, one need only examine a bus stop or a lamppost to see the impulse in action: for every pendulum swing towards order – timetables, zones – an answering knee jerk of ‘nope’. For every bland strip of public messaging, a defiant little tag. Like your big brother tipping over the sandcastle you’ve spent all afternoon working on, or writing ‘loser’ in his secret diary, those gestures are just as likely to be undertaken for their own sake as for a greater cause. And whether the target of that ire is a local council or a pesky sibling, the heart of a defiling gesture is always folded in on itself.

The decision to ruin something, after all, acknowledges the power of the unblemished original; that it is weighty enough, to an individual or a society, to merit ruining in the first place. What’s the difference between graffiti and a doodle if not context? The same design, in a notebook and on a public wall, will have vastly different resonances. One is just a drawing, and one is a statement – whatever it says, it says I was here too.

Think back to primary school. Am I revealing myself to be very, very old if I say that our desks were wooden? In any case, I remember zoning out of boring lessons and into the layers and layers of names and messages carved by year after year of under-11s. ‘You’re a twat’; ‘Your mum’s a twat’: ah, pure poetry, hacked into the varnish with an almost runic aspect. One child could answer another without ever meeting in real life, call and response separated by years – before landing with me, hunched over in maths, and passed on in turn like a game of Consequences when I whizzed off to secondary school.

Those reservoirs of rebellion were exciting – flowing beyond the reach of curriculums and headteachers, yet right under their noses! I wasn’t brave enough to write anything rude, but I did carve my initials with a ruler. I was not a naughty kid, and so the terror-thrill of venturing a toe outside school’s sacred sphere is yet to be surpassed. Beyond the playground, that same impulse which made me scribble on my desk – here’s a line, here I cross it – is sharpened and honed.

While some are content to stick with the basic slapping-their-name-on-stuff approach, inherently defiant because it resists the order of its authoritative canvas, others go further. These individuals understand the power of defacement, directing addressing the system of power which erects those smooth walls, road signs, public monuments, by disrupting it. And here’s the thing: no one bothers to topple a statue they don’t care about; to deface an idol without devotees. In a kind of metaphysical Venn diagram, the most strident act of destruction only cements the sacredness of the very thing it seeks to disempower.

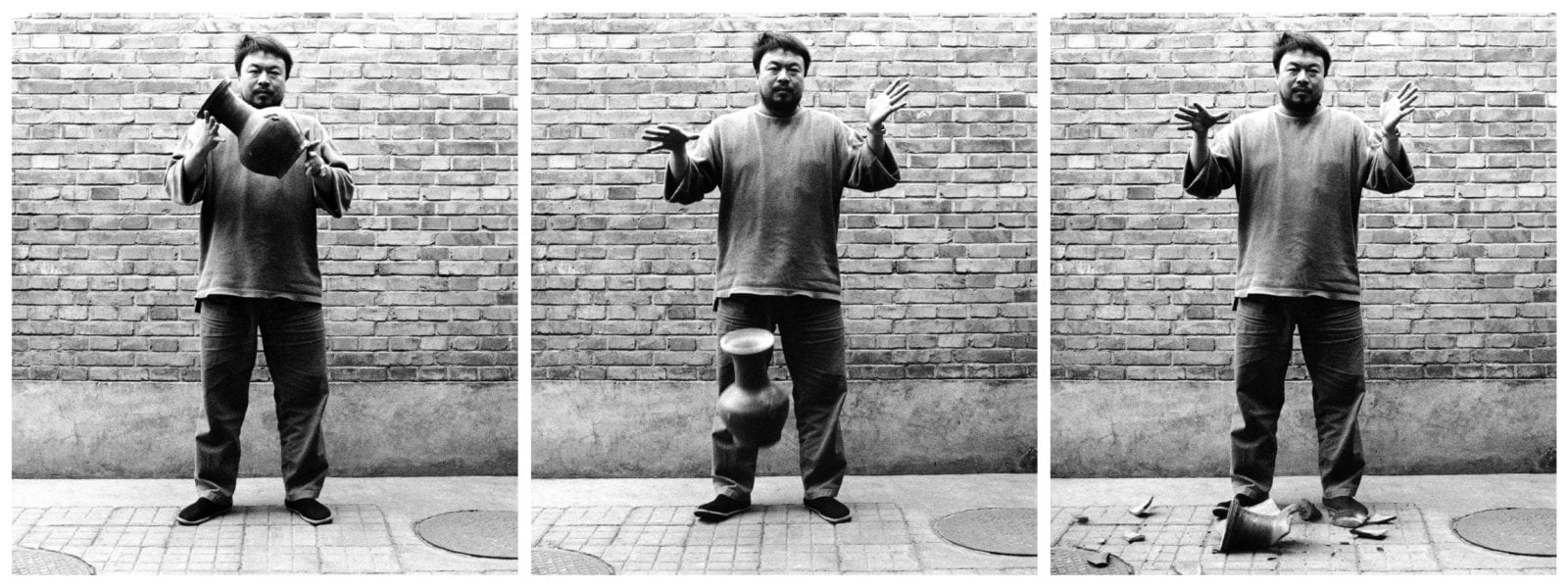

Ai Weiwei’s ‘Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn’, 1995, (the header image) taps into just that equation. The work does what it says on the tin, and takes the form of a series of photographs wherein the artist holds, lets-go-of and smashes a bona-fide artefact: an urn from China’s Han dynasty. At least 2000 years old, explicitly ceremonial, the urn could hardly be more charged with reverence – and that’s what makes smashing it interesting.

As Weiwei himself said in interview with Charles Merewether, 2003, ‘it’s powerful only because someone thinks it’s powerful and invests value in the object’. In destroying the urn, new ideas spring from its collision with the floor – it just wouldn’t be the same with a vase from Asda, would it?

First exhibited in the same year, Jake and Dinos Chapman’s infamous ‘Insult to Injury’ involved intervening on (‘rectifying’, in the artists’ words) a set of 80 Goya prints. Adding clown or dog heads over every visible character’s face, the works engage a similarly pearl-clutching instinct as Weiwei’s urn. Both dare us to face ourselves head on: are you finding this upsetting? Can you tell me why?

Francisco Goya, Sad Presentiments

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Sad Presentiments from Insult to Injury, 2003

A contemporaneous review by Jonathan Jones for the Guardian describes ‘Insult to Injury’, subjecting Goya’s masterpieces to scrawls which recall the horns and arrows-through-heads so ubiquitous on public photos of politicians (or just anonymous models in ads), as nothing less than ‘the last taboo of the liberal, Britart-loving, Tate Modern-going public.’ Depending how you’re feeling, that ‘last taboo’ is either a very exciting or a very scary prospect.

Musing in the same article about crime writer Patricia Cornwell’s purchase and destruction of Walter Sickert’s paintings (undertaken to prove her theory that Sickert was in fact Jack the Ripper), Jones is gratifyingly appalled. Cornwell acted to solve a mystery rather than make a point a la Weiwei or the Chapmans; nonetheless, ‘to destroy a work of art is a genuinely nasty, insane, deviant thing to do’, writes Jones.

But hold your horses.

What makes it more ‘deviant’ than covering a lovingly prepared dinner in washing up liquid? Ripping up your boyfriend’s suits, or burning family photos? Surely it all depends what you hold sacred – Jones is rather giving himself away even if he’s in on the joke, ‘I have fallen into [the Chapmans’] trap’.

For Jones’ Britart-loving, Tate Modern-going chums, the artists’ antics threaten to veer from naughtiness into sacrilege – from vandalism into iconoclasm. Iconoclasm might be a loaded term, but it’s a useful one; basically, it denotes defacement or destruction (see above, desk graffiti) with an ideological motive. While Weiwei’s urn and the Chapman Goyas arguably straddle both categories, history is teeming with more explicit examples from which they lift their precedents.

Enterprising Pharaohs in ancient Egypt used to carve their own faces over statues of their predecessors. The Olmecs made holes in their huge king-head sculptures, and Romans loved nothing more than scribbling on depictions of their ex-emperors. Think of the Protestant Reformation in England, basically a state-sanctioned campaign of straightforward smashing, or of last summer’s spate of statue felling. The more sacred an iconoclast’s target, the higher the stakes – and the bigger the backlash.

If you’re tempted to look at a wall covered in graffiti and sigh sagely, how disruptive, remember that disruption is the point. Ditto, the art critic bemoaning the destruction of a masterpiece, or a patriot raging about our history being erased as old slavers bite the dust. When, where, why: these variables might change, but the human impulse to communicate a metaphorical middle-finger by breaking stuff seems as irrepressible as it is perennially successful.

When that ‘breaking’ upsets someone, when that ‘stuff’ is invested with more power than the sum of its parts, all the better.

Otherwise, why bother?