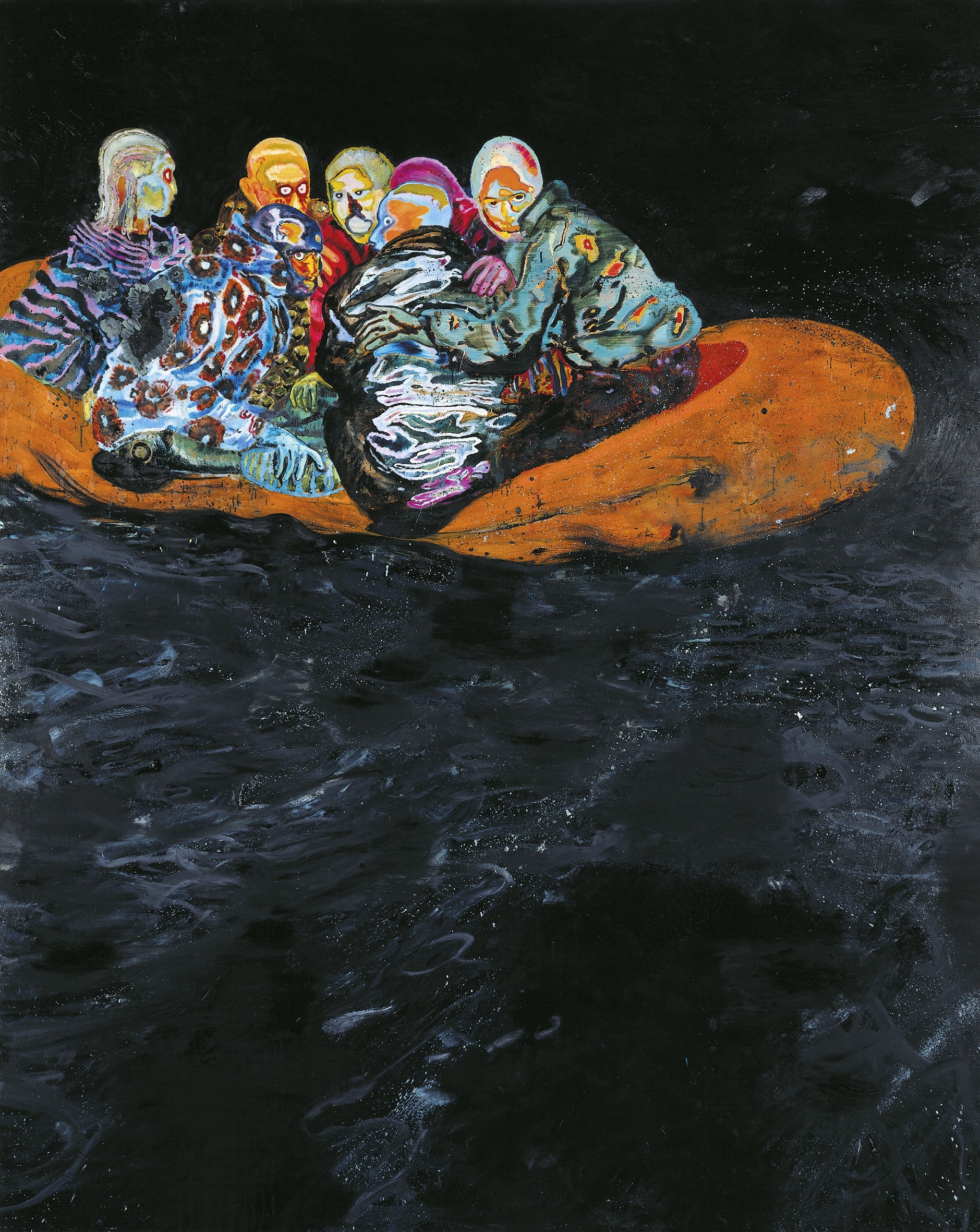

Daniel Richter, Tarifa, 2001, Oil on canvas, 350x280cm, © Daniel Richter / DACS, London 2019 Courtesy of Galerie, Thaddaeus Ropac, London, Paris, Salzburg

For painters in the new millennium, no shortage of challenges of which to keep abreast. The charge against painting’s conservatism and commercialism. The dominance of abstraction. Photographic images everywhere, on our phones and screens. To contend with which, the painters in Whitechapel’s Radical Figures exhibition are taking to the seas.

…the painters in Whitechapel’s Radical Figures exhibition are taking to the seas.

In Daniel Richter’s painting, migrants huddle together in a rubber dinghy. The orange boat looks soon to be engulfed by black paint, dark waters all around. Painted from news footage, ‘Tarifa’ (2001) pushes us towards the Spanish coast, where thousands of African migrants have attempted the crossing. Pulled up short by the slowness of painting’s process — and the painstaking consumption of its product, an image so frequently flashed at us in the news – the viewer pours her consideration into that temporal gulf. What are we looking at? And within which limits?

ArrayNicole Eisenman, Progress: Real and Imagined [left panel], 2006, Oil on canvas, 243.8 x 457.2 cm, Courtesy of Ringier AG / Sammlung Ringier, Switzerland

ArrayNicole Eisenman, Progress: Real and Imagined [right panel] 2006, Oil on canvas, 243.8 x 457.2 cm, Courtesy of Ringier AG / Sammlung Ringier, Switzerland

With the migrants abstracted by lurid colours — pink, orange, turquoise — Richter’s night vision effect draws that act of looking into the canvas. Surveilling the scene, are we the Search and Rescue team or Police Coast Guards? Try searching the figures’ eyes for an answer, and you find wide, terrified hollows. They almost-but-don’t-quite meet our gaze. Rather, we have the privilege-cum-burden of judging them; time, twisting their urgency into the glacial pace of a brushstroke.

Surveilling the scene, are we the Search and Rescue team or Police Coast Guards?

Cecily Brown, too, puts the viewer at sea. The shipwreck is one of humanity’s oldest metaphors: from divine punishment in mythic tales of great floods to moments of failure along life’s journey. In its serene palette — blues, whites, terracottas — and its title, ’The Last Shipwreck’ (2018) suggests we might someday overcome such monumental ruination. Then again, Brown’s flurried mark-making is chaotic — perhaps, this is just the latest in a long chain of disasters.

Cecily Brown, Lucky Beach, 2017, Oil on linen, 210.8 x 170.2 cm, Collection of Laura and Barry Townsley, London, © Cecily Brown. Courtesy of the artist Thomas Dane Gallery, and, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Cecily Brown, Oinops, 2016–17, Oil on linen, 170.2 x 154.9 cm, © Cecily Brown. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

As demonstrated by its neighbouring Richter painting, boats compress a crowd of people into a liminal space; Brown’s, though, refuses to contain them. Ever involved in a push-pull between the figurative and the abstract, you can make out the black form of a boat, emerging as if from a frenetic, arching wave. Just about. More pertinent is the way that everything spills over. The waves into colour. Shape into action. The boat is both a vessel for the nervous energy of its own creation, and a signifier of its failure to contain it too.

The boat is both a vessel for the nervous energy of its own creation, and a signifier of its failure to contain it too.

From shipwrecks, to the places where they wash you up – though you wouldn’t want to be stranded on one of Dana Schutz’s beaches. In ‘Suspicious Minds’ (2019), grotesque figures jostle for space under a striped beach umbrella.

ArrayDana Schutz, Imagine You and Me, 2018, Oil on canvas, 223.5 x 223.5 cm, Courtesy of the artist; Petzel, New York; Thomas Dane, London; Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

These boulder-headed men might have found shade for now, but the fish bones littered and bleaching in the golden sand around them suggest they might soon have to tussle for food. While the tableau’s impish simplicity rebuffs too close a reading, I can’t help but see contemporary suspicions – they took our jobs / he stole my umbrella – amidst the canvas’ tense cast of characters.

I can’t help but see contemporary suspicions – they took our jobs / he stole my umbrella

Nicole Eisenman’s huge diptych ‘Progress: Real and Imagined’ (2006) is as busy as any Bosch or Breughel. In the right panel, waves lap at arctic shores. There is So. Much. Going. On. — hunting dogs, fishing, decapitated heads, a water-birth — that I’ve only just noticed a fleet of hamburgers in the distance, orbiting like UFOs. Advancement, or apocalypse?

Dana Schutz, ‘New Legs’, 2003, Oil on canvas, 152.4 x 167.6 cm, Courtesy of the artist; Petzel, New York; Thomas Dane, London; Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Daniel Richter, Asger, Bill und Mark 2015, Oil on canvas 200x270cm, Sammlung Lutjenburg

Meanwhile, the left panel shows an artist hard at work in a studio-cum-houseboat. All is in motion. Reference images slice through the air. Flowers spatter from a vase like sparklers. The entire scene, saved from drifting off by two bearded seamen clutching either end of an oar.

Here the sea — frame, reference, subject — brings everything together (literally crossing over from one panel to another), tossing the narrative into motion, even as it threatens to jettison the artist. Movement and risk necessary for creation.

All is in motion. Reference images slice through the air. Flowers spatter from a vase like sparklers.

Ocean as evergreen metaphor – for progress, real or imagined — has enjoyed no shortage of spotlight throughout art history. It’s also a hotly contested site in our contemporary moment: refugee crises, burkini bans, pollution and rising global temperatures, situate the sea at the heart of some of our most dearly held convictions and fears.

Beyond connotations of progress, waves and tides are as good a metaphor as any for uncertainty. Fluidity. As we make our tentative way into this new millennium, not knowing where it might lead, we might well feel a little at sea. Here are the artists drawing their context into their canvases, re-charting charted waters. Whether it’s Richter’s infrared, Brown’s chaotic placidity, Schutz’ sunny absurdity, or Eisenman’s beguiling allegory, here are painters making waves.