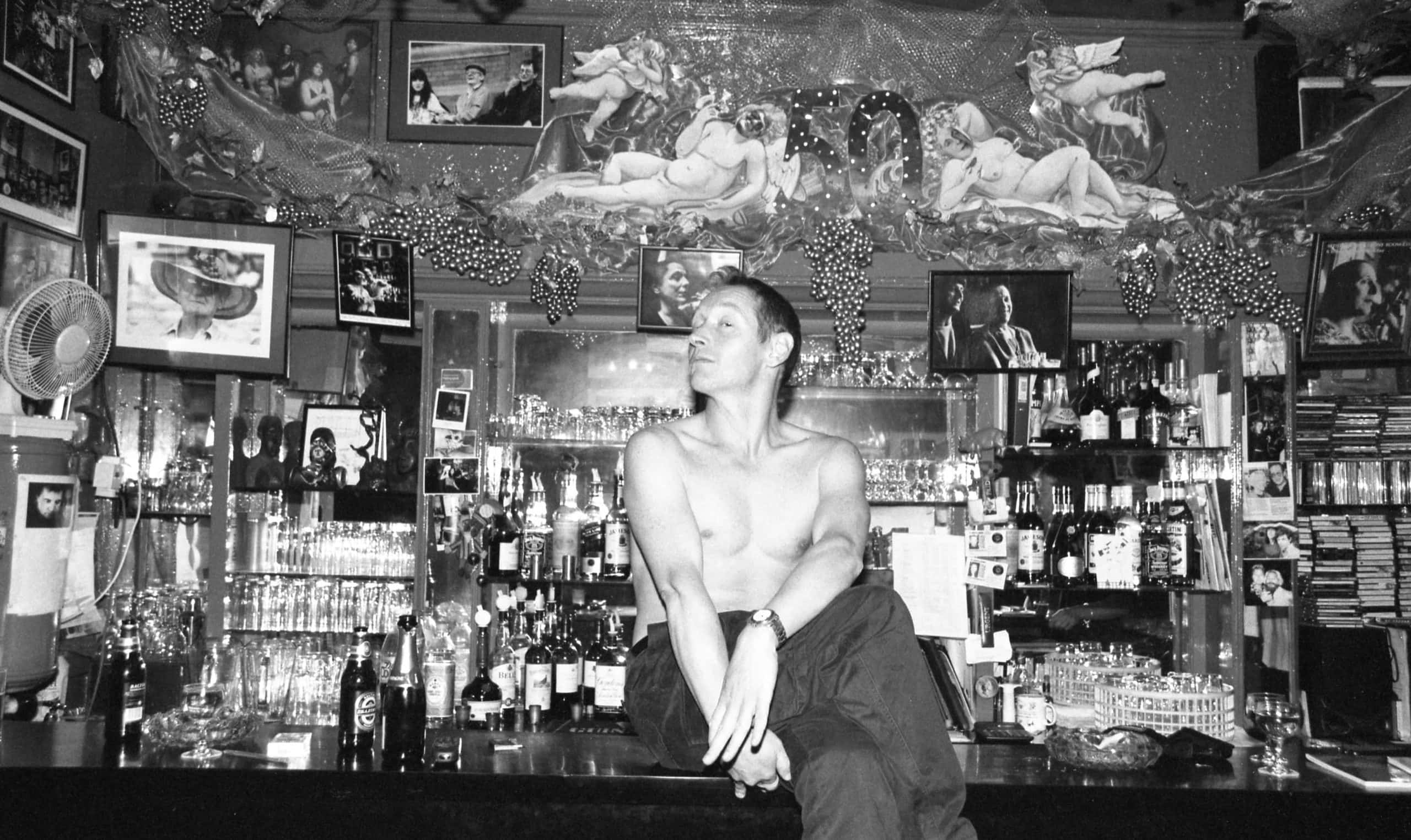

John Goldblatt

Untitled, from the series ‘The Undressing Room’, 1968 © John Goldblatt

Courtesy of the artist’s estate

By Eva Clifford

For decades, Soho has prided itself as a place of acceptance and individuality. It has lured artists, outcasts and subcultures, becoming an epicentre for the music, fashion, design, film and sex industries – as well as a refuge for LGBTQ+ communities and immigrant populations.

While much of its trademark sleaziness may have fallen away over the years, Soho remains the city’s creative heartbeat. Having survived massive transformation and overcome adversity, Soho now faces a greater threat: a major transport hub being built on its borders.

While much of its trademark sleaziness may have fallen away over the years, Soho remains the city’s creative heartbeat.

Shot in Soho – an exhibition held at The Photographers’ Gallery in Soho itself – captures the spirit of London’s most rebellious district through the lenses of seven photographers. Curated by Karen McQuaid and Julian Rodriguez, it seeks to “celebrate Soho’s diverse culture, community and creativity at a time when the area is facing radical transformation.”

William Klein – the renowned American-born French photographer – opens the exhibition with a blown-up photograph showing a group of men exiting an establishment called ‘69 Sauna & Massage’. Caught off guard, the group shield their faces from Klein’s in-your-face flash. Despite the blatant intrusion of their privacy, the men looking directly at the camera are seen laughing. One of the men wears a ring on his ring finger, but as Klein’s photo suggests: men didn’t go to Soho with their spouses for a reason.

ArrayCommissioned by The Sunday Times Magazine in the 1980s, Klein’s Soho series has lain forgotten in his archive ever since. Now seen for the first time on gallery walls, the photos depict a range of Soho characters from gunsmiths, skinheads and drag queens, to an elderly couple in the street peering into a sex shop as they pass.

…from gunsmiths, skinheads and drag queens, to an elderly couple in the street peering into a sex shop as they pass.

Clancy Gebler Davies’ The Colony Room Club (1998-2001) is another lesser-known work, which ushers us behind the doors of a private members’ club. As one of the more grungy members-only clubs, Davies describes The Colony Room Club as “the equivalent of skulking off behind the bike sheds to have a fag.” A place where people drank on an industrial scale, carpets were filthy and the air was perpetually hazy with cigarette smoke. Davies gained full access to the club after charming her way in for a dare, but after the owner confronted her about an extensive bar bill, she began working shifts there to pay it off.

William Klein Men hidden their faces / 69 Sauna & Massage © William Klein Courtesy of the artist

By the late nineties, the Colony was frequented by young British artists including Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Tracy Emin, as well as noted writers, journalists and musicians. While photos were technically forbidden, Davies was trusted enough to roam freely with her camera. Mounted on a lurid green to evoke the original colour of the club’s walls, the candid photos reveal an out-of-bounds and potentially intimidating domain in an unexpectedly tender light.

Elsewhere, the Swedish photographer Anders Petersen’s gritty black-and-white photos conjure an image of him as a somnambulist. Having focused his first project Cafe Lehmitz (1978) on strangers; drinking with them and befriending them, this Soho series shot in 2011 uses a similar method (in that he is less of an observer and more of a participant). As a result, the images take on a diaristic quality.

Devoid of context, they develop like a string of snapshots from a drunken night out, full of mysterious, half-forgotten encounters. The image of a man hanging off a pole in the street furthers the idea of the street as both stage and playground. Yet despite the implied joy of some of his shots, ‘poetic sadness’ is the expression Petersen uses to describe his own images. Intentionally dark and broody, each picture seems to have a narrative of its own – stories that we will never know.

ArrayJohn Goldblatt’s The Undressing Room (1968) is the result of four consecutive evenings at a Soho strip club. Rather than being intrusive, the images are intimate and relaxed. The women – most of them nude – appear at ease with Goldblatt’s presence. His timing is exact and evidently he has an eye for capturing tender, off-guard moments.

Covering scenes with the West End Central police, aka the Soho ‘sweeps’, London-born photographer Kelvin Brodie reveals the authority’s attempts to tame Soho’s wild streak, in his series Soho Observed (1968). Accompanying police on various raids and rescue missions, Brodie gained a firsthand insight into the criminal underworld. Unseen since they were first published, his pictures unfold like a wordless soap opera.

The inclusion of Corinne Day’s photography is unexpected but fitting, due to the fact she was a Soho resident and the series was shot in her Brewer Street flat. In The Brewer Street Work (1990-2003) she captures the endless stream of friends and models that filtered through her home between and during shoots in that prolific period of her career.

Clancy Gebler Davies The Colony Room Club, 1999 – 2000 © Clancy Gebler Davies Courtesy of the artist

Daragh Soden / Looking for Love, 2019 / © Daragh Soden Courtesy of the artist

Anders Petersen / Soho, 2011 / © Anders Petersen Courtesy of the artist

The exhibition’s most contemporary work is by the young artist and photographer Daragh Soden, who was commissioned by the curators to create a contemporary portrait of the area. His response – Looking for Love (2018) – focuses on Soho as a place where people hunt, find and lose both love and lust. In addition to a short film and a series of illuminated screenshots from dating apps, he presents close-crop photographs that hone in on details: a jukebox, a rose, a stairwell… which at first seem disjointed, but serve as enticing prompts for the viewer to form their own narrative.

…a place where people hunt, find and lose both love and lust.

Shot in Soho is largely an ode to what Soho once was, capturing the resilience of the area in spite of a continuous undercurrent of change. Through the eyes of seven photographers, the images bear testament to the enduring spirit of Soho as both a refuge and a playground, where inhibitions run wild and every street corner has an unwritten promise of possibility.

ArrayFrancis Bacon and George Dyer, An Alcoholic Romance

By Raphael Tiffou, Arts Editor

There are of course exceptions to this tale of Soho acceptance, and it is most formidably seen in Francis Bacon’s relationship with his East End lover/burglar/muse/close friend George Dyer. Although Dyer welcomed the attention Bacon’s paintings brought him, he did not pretend to understand or even like them. “All that money an’ I fink they’re reely ‘orrible,” he observed with choked pride.

Bacon’s money attracted hangers-on for massive benders around London’s Soho. Withdrawn and reserved when sober, Dyer was highly animated and aggressive when drunk, and often attempted to “pull a Bacon” by buying large rounds and paying for expensive dinners for his wide circle.

Bacon’s money attracted hangers-on for massive benders around London’s Soho.

Dyer’s erratic behaviour inevitably wore thin with his snooty cronies, with Bacon, and with Bacon’s friends. Most of Bacon’s art world associates regarded Dyer as a nuisance – an intrusion into the world of high culture to which their Bacon belonged. Dyer reacted by becoming increasingly needy and dependent. By 1971, he was drinking alone and only in occasional contact with his former lover, and by October he had died suspiciously in Paris on the eve of Bacon’s largest retrospective thus far.

Anders Petersen Soho, 2011 © Anders Petersen Courtesy of the artist

One of the more striking photographs in the exhibition unpicks this feeling perfectly – an almost god-like Bacon is surrounded by his gaggle of admirers set behind a table heaving with the weight of alcohol. In another, he sits with Lucian Freud and several others on a table in a framing reminiscent of a last supper – they stare at the photographer with the expressions of 50s schoolboys.

The Colony Room Club finally closed in 2008, after providing London’s artists with industrial quantities of alcohol for several decades. In his epitaph for the Club, novelist Will Self argued against the view that the closure demonstrated that ‘the old Soho is being killed off by smoking bans and other sanitising measures.

Corinne Day, Georgina Cooper

Interview Magazine, ‘That imaginary Line’, January 1996 © The Corinne Day Archive

Courtesy The Corinne Day Archive

The truth is that there was another criterion for membership: the hardcore members were first and foremost raging alcoholics.’

Whilst the hedonism has been pushed to the basements, behind closed unmarked doors and invite-only gatherings – it is still there, beating away, pumping life into the clueless tourists above.