The Pop Artist’s enormous sculptures were big, bold, and often witty – but many lacked heart or meaning.

Swedish-born American sculptor Claes Oldenburg (1929-2022) died in his home city of New York, on Monday, aged 93. He was one of the leading figures of the US counter-culture in the 1960s and early 1970s. Ironically, some his most distinctive achievements became a template for corporate art of the 2000s.

Oldenburg studied art in at the Art Institute, Chicago before relocating to New York. At a time, the Abstract Expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko dominated the galleries and art schools. Soon they would come to dominate the auction rooms. Once rebellious modernist abstraction would grace the walls of tycoons’ office walls of tycoons and socialites’ Long Island homes. Young artists in the late 1950s rebelled against what they saw as the commodification of art by staging free art performances (called “Happenings”). Oldenburg and his first wife participated in these.

Claes Oldenburg, Tartines, 1964, plaster painted with tempera, on porcelain plates, glass and metal case

Oldenburg had been born in Stockholm and moved to the USA in the 1930s, where his father was a diplomat. He became an American citizen in the 1950s and is considered culturally American. Growing up in economic boom of World War II and the post-war period, the young artist was struck by the plethora of cheap food and consumer goods. He started to produce plaster sculptures of food, which he then painted. The results were like window-display samples. He sold these in an improvised gallery that he called The Shop.

Treating art as a commodity flew in the face of the abstract painters’ statements about art being spiritual enlightenment and personal exploration. Oldenberg found himself part of the emerging Pop Art movement. The movement produced art that defied high-culture expectations, using pre-existing images. Examples are Andy Warhol’s screenprints of celebrities and Roy Lichtenstein’s large painted versions of cartoon panels. Oldenburg made cheap fun art like holiday souvenirs, undermining the seriousness of high art.

Oldenburg followed this up with “soft sculptures” – household objects made in vinyl and stuffed. The saggy typewriters and bulging washing machines were sad pathetic objects that functioned as stand-ins for originals. He made soft sculptures of food, blown up to giant scale. The sculptor’s subversive outlook came to the fore in his temporary museums of ephemera, such a toys, ornaments and packaging. The collections acted as mirrors, reflecting back to society the production of unnecessary goods and the weirdness of normal life.

Claes Oldenburg, Giant BLT (Bacon, Lettuce, and Tomato Sandwich), 1963

The art that made Oldenburg’s reputation, and left a lasting impact, were his giant outdoor sculptures. Oldenburg had been making larger versions of common objects for years, but he wanted to make public sculpture – statements that would confront people and force them to think. His sculpture of tank tracks carrying a giant lipstick was conceived in 1969. It was intended as a critique of the Vietnam War, turning a symbol of might and machismo into something silly and strange. The final version took five years to make and was installed in the plaza of Yale University. By situating a sculpture that mocked war in a place where intellectuals, engineers and politicians trained, Oldenburg intended to take on war supporters in their home territory. Of course, due to student mobilisation, Yale University was also a centre of resistance to the war.

“Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks,” (1969). Credit: Claes Oldenburg; via the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

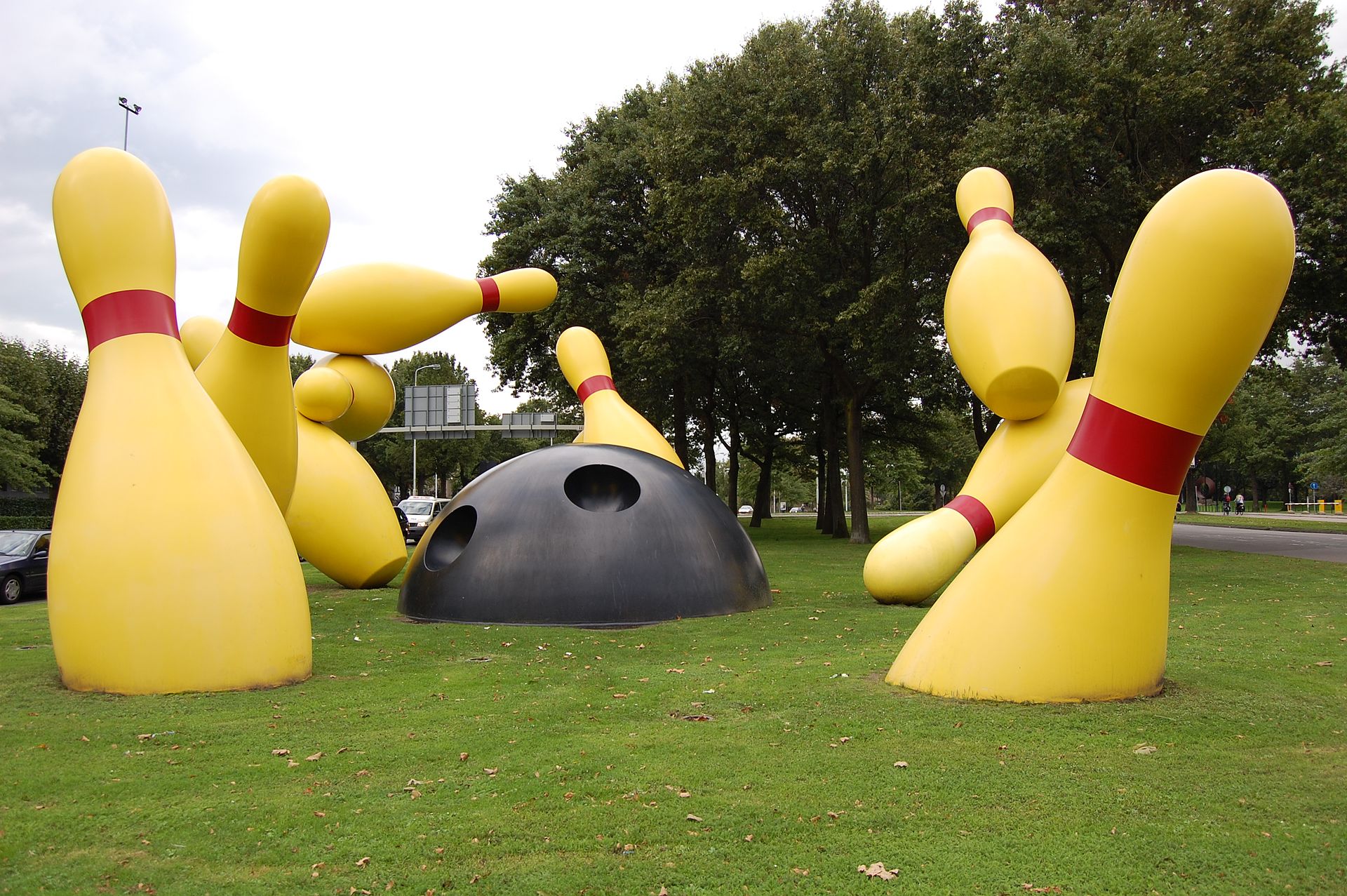

Oldenburg had long been prompting people to think about (and engage anew with) everyday surroundings. Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks (1969–74) was the sculptor’s most political, famous and effective public sculpture. Later giant public sculptures – made in collaboration with his second wife, Dutchwoman Coosje van Bruggen – were more playful and whimsical. These included a bowling ball and pins, a dropped ice-cream cone and a spoon and cherry.

Flying Pins by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Eindhoven, Netherlands

‘Dropped Cone’ by Claes Oldenburg in Cologne, Germany

Spoonbridge and Cherry in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden

It was these simplified, giant objects – influenced by the Surrealism of Magritte, as much as they were by Pop Art – that became a template for public sculpture. They appealed to local governments seeking to stimulate tourism and to corporations, which were obliged by law to spend a certain percentage of every large building project on public art. Notable examples include an eyeball and mechanical flowers.

Oldenburg’s ‘Eyeball’ sculpture in Manhattan

Although some of these sculptures are witty, many lack heart or restraint. While they added liveliness and humour, critics claimed they detracted from civic spaces in terms of dignity and integrity. These comic interventions in public spaces tell us something about our lack of confidence in our heritage and a fear of seriousness. It is ironic that Oldenburg’s first public sculpture was an objection to a military-industrial complex profiting from war – humour with a moral message. How much he himself took the sting out such public sculptures by later producing more whimsical pieces is an open question. What is not in doubt is the creativity and huge influence of Claes Oldenburg, counter-cultural sculptor.