Photographer Cate Dingley documents New York’s African-American motorcycle clubs, discovering the humanity beneath aggressive stereotypes.

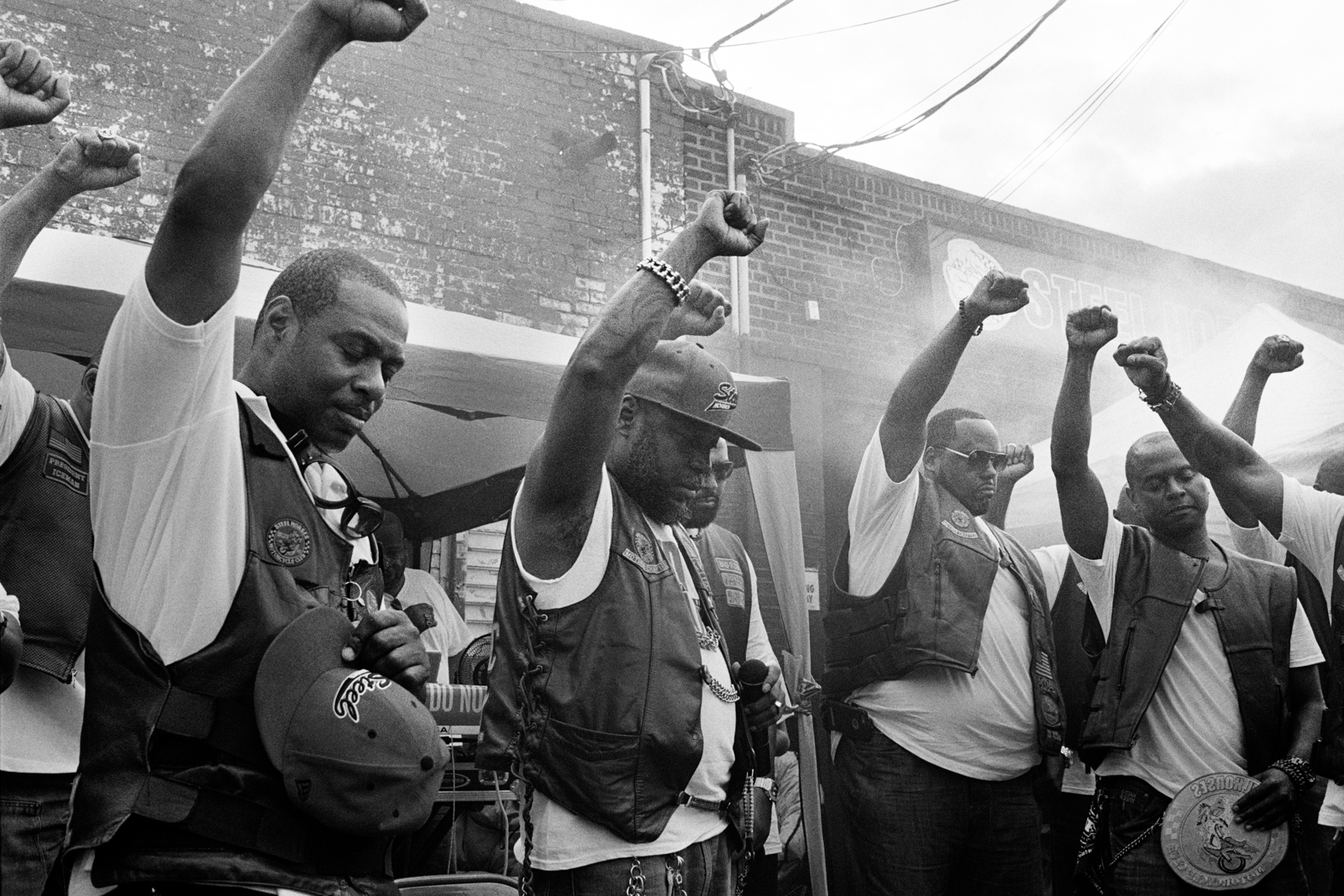

Above: Vice Prez Skip of Steel Horses leads a prayer for victims of violence (Brooklyn 2016)

For decades, the collective sound of engines rumbling into town has been a foreboding noise, a sound that precedes the notorious motorcycle gangs which since the 1930s have been shunned as trouble-makers, associated with violence and crime. But as a documentary photographer with an interest in people who occupy a “transgressive existence on the edge of visible society”, these are exactly the kind of misconceptions that Cate Dingley is intent on challenging. Her ongoing long-term project Ezy Ryders documents New York City’s African-American motorcycle clubs (MCs) and gives a nuanced take on this scene, revealing a humanity that is often overlooked by the negative stereotypes.

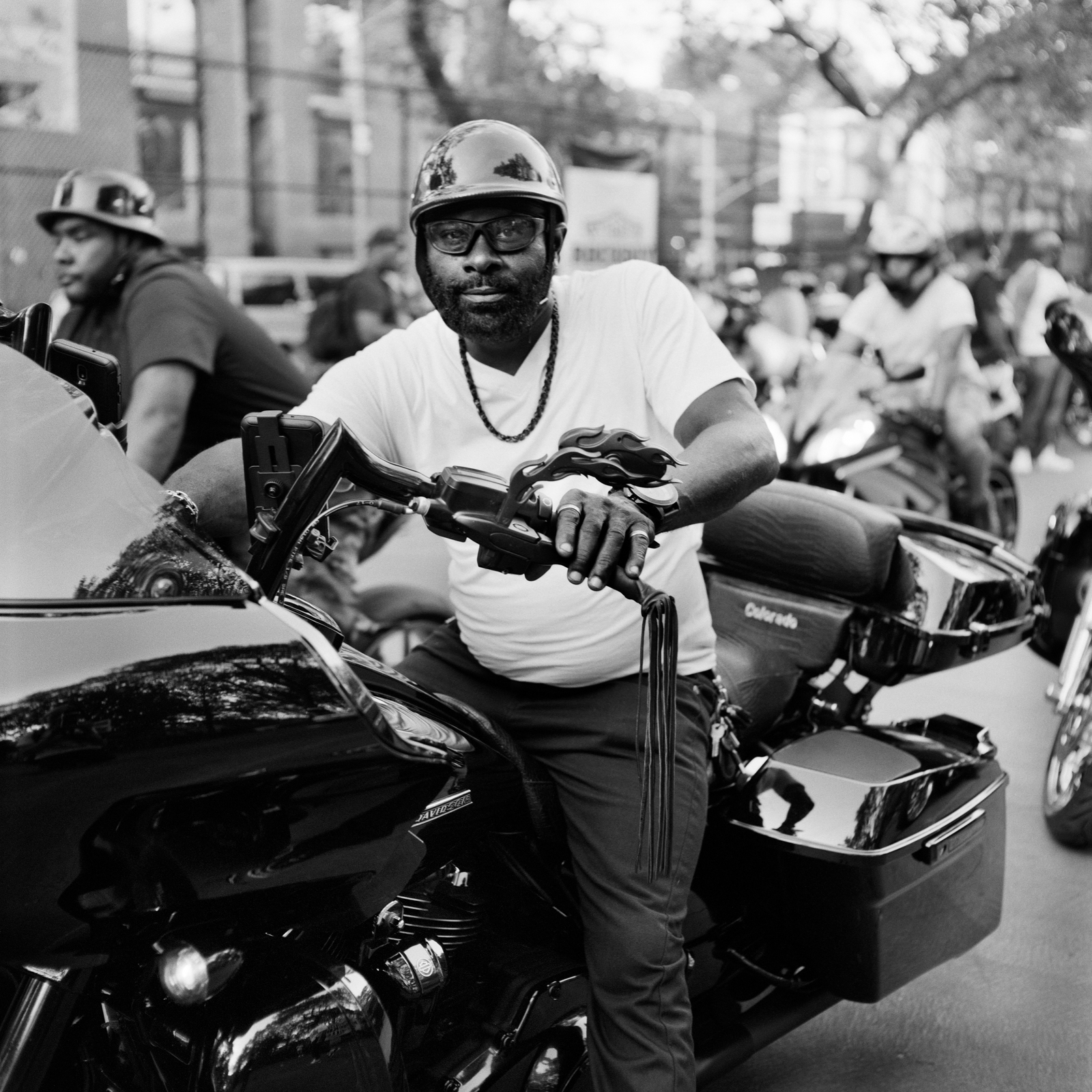

In 2014, Cate was introduced to a Trinidadian motorcycle club in Brooklyn through a mutual friend. Living in New York City she’d seen black bikers before, but it wasn’t until this encounter that she realised the sheer scale of the culture, which is present in all five boroughs of New York and comprises hundreds of MCs and thousands of riders. Though the prevailing image of these clubs is predominantly white and male, she soon discovered that the history of African-American MCs (as well as female MCs) goes back just as far, even if their contributions have been largely ignored. After meeting the club and attending a barbeque – where hundreds of riders were gathered – a world she previously had no idea existed suddenly opened up to her, and Cate knew it was something she wanted to explore further.

Prez Shifty of Blaque Pearls MC outside her home (The Bronx 2018)

Through the process, Cate found that it was not only other people’s preconceptions she was challenging, but her own biases too. “I love it when people surprise me,” she says over email. “Bikers are thought of as a monolith, and black Americans often are too – these riders have so many assumptions about them to contend with. But NY MCs are too numerous and diverse to generalise about.”

“It was a privilege to be able to spend the time that I did with NY’s black bikers and go deep into the scene,” she adds. “I tried to wade through the ideas society has about them, and the image that the bikers themselves like to present to the public and find all the gritty nuance underneath.”

From the outset, Cate knew this wasn’t going to be easy. She’d never ridden on a motorbike before but to gain respect and trust, she knew she had to fully immerse herself in the community. For Cate, this meant forming friendships with the MC members, accompanying them on runs and attending events and gatherings.

“In the MC world it’s all about who you know,” says Cate. “Coming into the set, any outsider will be met with suspicion. I expected this and respected the long process of building trust. It took about a year to feel like people were starting to accept my presence. Word gets around fast on who’s to be trusted and who isn’t.”

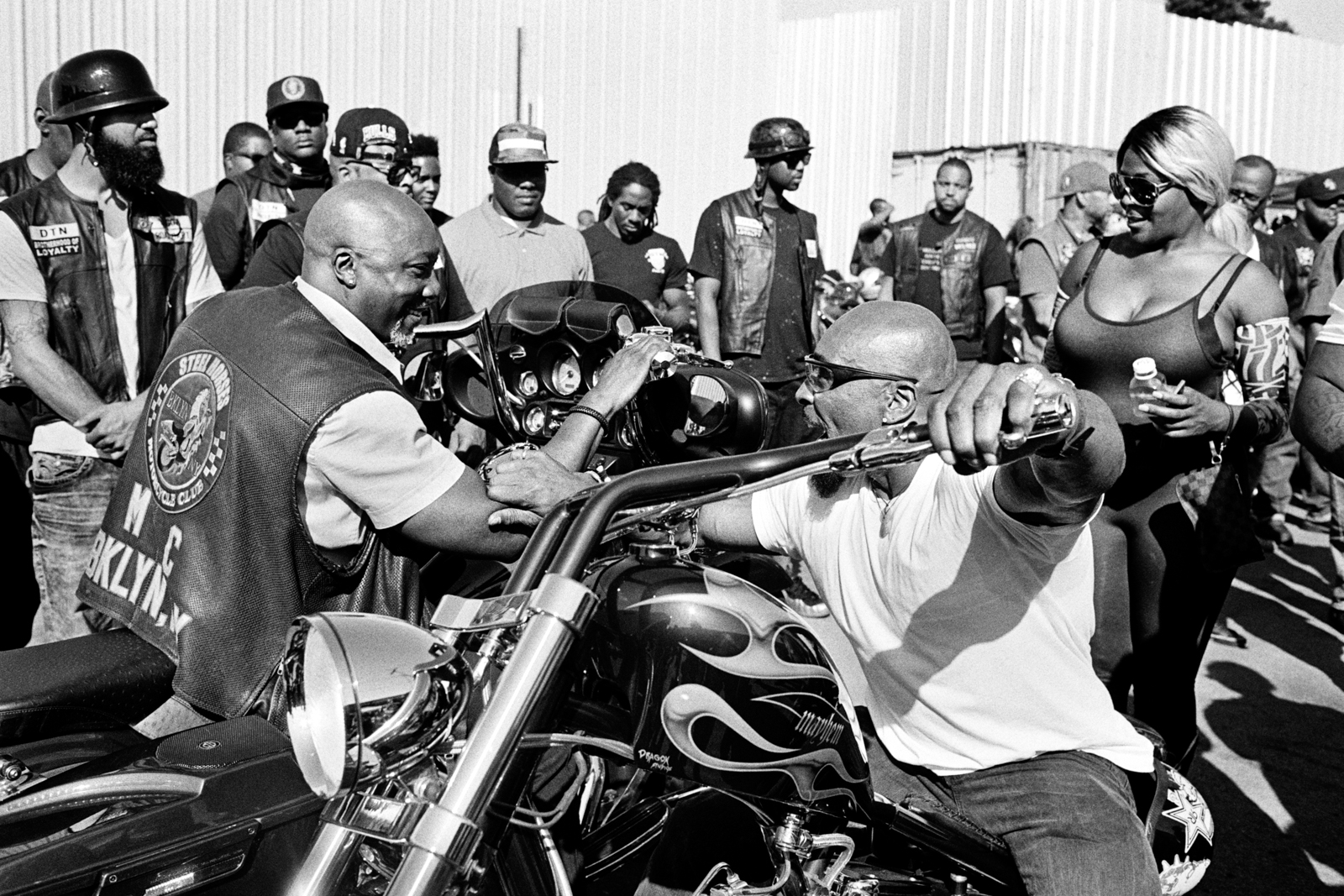

Friends greet each other at the Steel Horses MC bike blessing. This blessing is one of the set’s biggest events of the year, sometimes drawing up to 2,000 riders—everyone is welcome and everyone shows up (Brooklyn, 2017)

Tony & Lizzy about to ride out, The Bronx 2016

Prez Choice’s kids outside Black Falcons (The Bronx 2016)

This first-hand experience led Cate to discover a flipside to the negative stereotypes. “What surprised me most is how family-oriented the MC world is,” she says. “At almost every gathering I went to, wives, husbands, kids and cousins of the club members were welcome and participating. The MC becomes a vast extended family where blood and water are equally thick.”

Through spending time with them, Cate learnt to differentiate between standard MCs and those who self-identify as Outlaws, or “1%ers” as they’re typically known. “It is said that 99% of MCs are law-abiding and clubs are formed simply to ride and forge bonds with their fellow members. And that’s exactly what I witnessed,” says Cate. “[The 1%ers] are very much the minority and relatively open about what they are.”

Gradually accepted into the fold, Cate started doing formal interviews for the project in 2017 and was surprised at how open and honest the bikers were, despite having photographed them for five years. In her newly-published book Ezy Ryders (named after a Jimi Hendrix song), Cate has included the testimonies of 10 bikers, which help defy the myths and stereotypes that are so often enforced upon them – including the idea that all clubs are formed of old white dudes.

“One of the riders interviewed is from a club called HOOD Ryderz, which has roughly equal numbers of women and men and members of numerous ethnicities. Inclusive clubs like this one seem to be the most common,” explains Cate. “Another rider interviewed is the President of a club called the Blaque Pearls, which is made up of women of different races. This president argues that an all-female club avoids the drama of co-ed clubs and focuses more on riding and sisterhood. Growing up she rarely saw women motorcyclists, but this demographic has exploded in recent years.”

Rider in Bed-Stuy (Brooklyn 2019)

Blaze talks to DJ Zok at Black Falcons clubhouse (The Bronx 2016)

The Ghetto Coalition on their annual Pamper Run (Manhattan 2017)

The clubs are also not limited to a particular age group. Cate found that some riders grow up on the scene, with kids as young as five riding bicycles or tiny motorised dirt bikes at club events – and she has dedicated part of her book to these “little bikers”. “Sometimes I asked people ‘when will you stop riding?’” Cate says. “The answer unanimously was ‘when I absolutely have to’. I know bikers in their eighties who still ride.”

For the members, ties of loyalty run deep and there is a sense of responsibility that comes with that. Frequently, Cate witnessed the clubs coming together in times of need to support the community, from mentoring young people to collecting coats for the homeless. One photograph taken in July 2016 shows a group of bikers with their fists raised in solidarity.

This was at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement was gaining traction and the summer of 2016 had been brutally violent, recalls Cate. “Unarmed black women, men and children had been gunned down across the country and two NY cops had been murdered while sitting in their patrol car. Vice President Skip of the Steel Horses MC, with the cap on, is at this intersection – he’s a NYPD detective, and (obviously) a black man. At the Steel Horses bike blessing, which draws thousands of riders, Skip decided to get on the mic and offer a message of unity, hope and justice. Everyone needed some light and comfort and for that brief moment they received it – you could feel the community come together. It was a powerful moment to witness.”

“For me, Ezy Ryders is a story of triumph and joyful rebellion,” concludes Cate. “This is a culture that has thrived over the decades, even while black and women riders’ contributions have been overlooked. I hope viewers can set aside any stigmas they hold about bikers and acknowledge the New York riders’ history, their tenacity, and their strength.”

Ezy Ryders is available to pre-order now. Click here for US pre-orders and here for EU & UK pre-orders. To see more of Cate Dingley’s work visit her website.