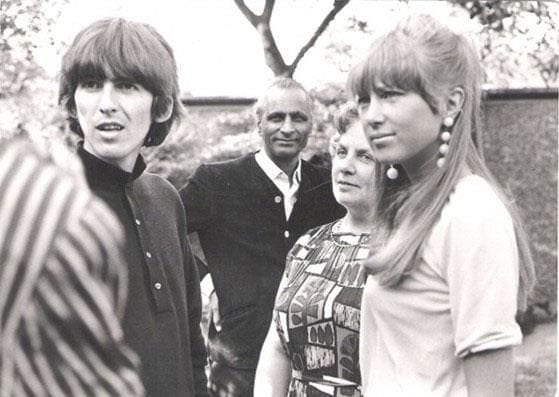

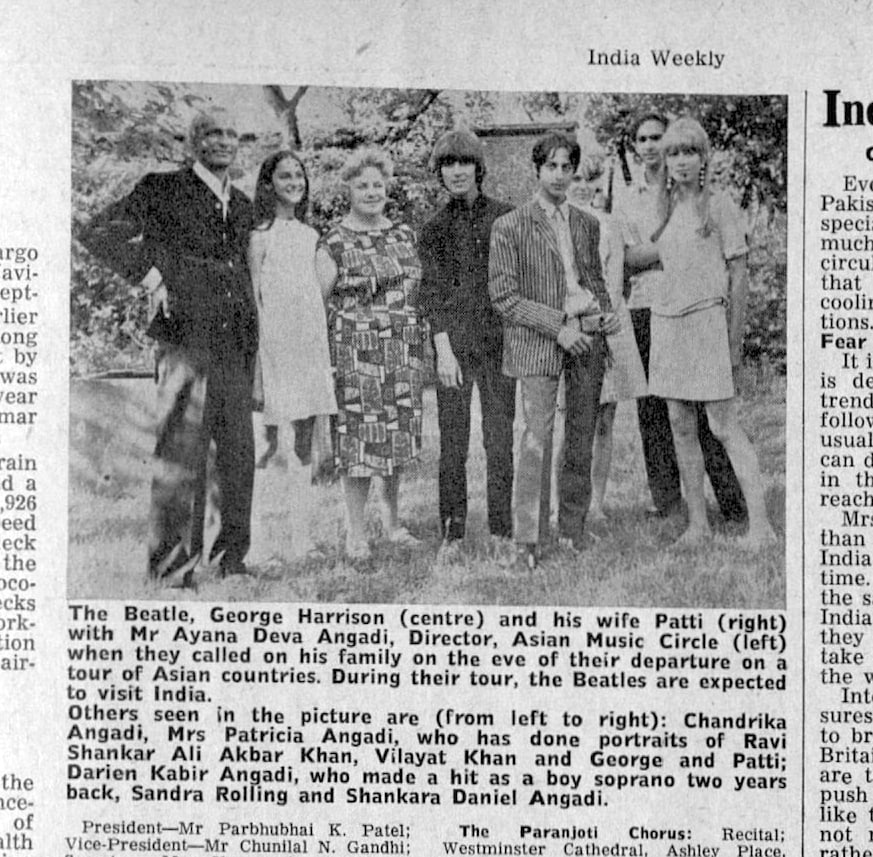

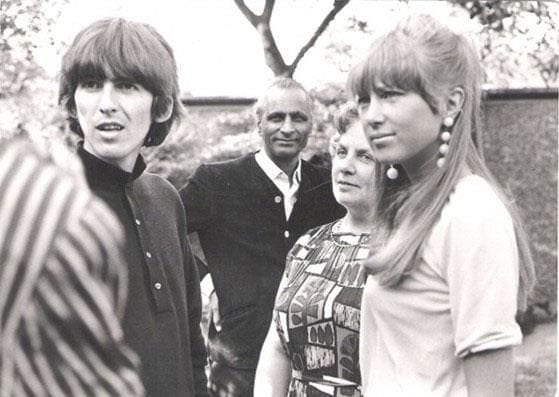

The new friends appearing in India Weekly: George Harrison and Patricia Angadi’s family became close friends after the Beatle asked Patricia’s husband Ayana if he had a spare sitar string to replace George’s broken one

One evening in 1965, 12-year-old Chandrika Angadi was sitting in her father’s study when the phone rang. “I overheard my father on the telephone,” she recalls, “saying, ‘did you say your name was Bingo?’ And then: ‘Oh, I’m sorry, Ringo!’.” Chandrika’s father, Ayana Deva Angadi, had just received a phone call from Ringo Starr. George Harrison had snapped a sitar string during the recording of ‘Norwegian Wood’, and did Ayana have a spare that he could bring to Abbey Road Studios?

“I just started going mad,” Chandrika told me, “making frantic signals to him. And then [my father] said ‘yes we do have a sitar string’. So we all got into the car – my mother, my father, and I.” Inside the studio, her mother, Patricia, sat down to sketch Paul and John, who were playing chess, while Ayana, “got down all their phone numbers and said: ‘We live in Finchley, and we often have musicians and dancers stopping by, we have concerts at our house […] do drop by anytime you like, and you can listen to some music, or play some music, or do whatever’. He was very charismatic.”

And George Harrison did phone, a few weeks later. Chandrika broke the news to her mother – who had just come home from work. “I said ‘oh by the way George Harrison is coming for dinner tonight’ and she said, ‘oh for goodness sake’ because she had nothing in the house. But she could always whip up a sort of egg curry – you know, something Indian, because it was always cheap and cheerful.”

Search for the Angadis on Google and you’ll get bits and pieces of apocrypha and Beatles-related mythology: dates that don’t match up, stories without sources, and poor quality photographs that you have to squint to see. But the more you search, the more you want to find out. Here is this suburban family, standing in their garden in Finchley beside George and Pattie Harrison, the father a left-wing Indian intellectual, the mother an upper middle class white lady with coiffed hair and prim 1950s dresses: not exactly the tie-dye radicals you’d expect to see in connection with The Beatles’s pioneering sound of ’66. So just who were they?

George Harrison, Ayana Deva Angadi, Patricia Angadi, and Patti Harrison

Ayana Deva Angadi, Chandrika tells me, was a very bright Indian student who came to London in 1924, “with the idea of sitting the Indian civil service exam. But he was very interested in Gandhi’s Quit India Movement, and left-wing politics in general, so he never sat the exam.” Instead, he “enrolled in various university courses, studied this and that, and then kind of dropped out of sight.” Well, not quite out of sight: the police were keeping tabs on him as a suspected Cominform agent, thanks to his Trotskyist publications and lectures at Hyde Park Corner.

Eleven years younger than Ayana, Chandrika’s mother Patricia came from an affluent, upper middle-class family in Hampstead. She had been to boarding school and then to finishing school in Paris; she had been a Debutante; had been presented at court to the King and Queen; and had spent her adolescent years on elite cruise-ships, seeing the world and mingling with the rich and famous at glamorous parties. But, as the youngest child of her very proper family, Patricia, who was born in 1914, found herself on the cusp between polite Edwardian society and an emerging modern sensibility.

Patricia Angadi and Suharmi Sentanu

Though neither a rebel nor a radical, the young Patricia was open-minded and boldly self-assured – and so, after enrolling at art school in 1933, she quickly found herself moving in bohemian circles. Her unpublished memoir reads like a roll-call of some of the twentieth century’s most illustrious names: Cecil Beaton, Vincent Price, Benjamin Britten, Ravi Shankar, Jacob Epstein, Marlon Brando (who once called Patricia “a very sensuous woman”), Brian Jones, George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Simon Callow, and many more make cameo appearances from the 1920s right through to the 1990s.

Patricia first glimpsed Ayana from the top deck of a bus in 1939. Gazing out of the window, her head swivelled at the sight of a “stunning looking Indian striding along Fulham Road in a scarlet shirt with a fiercely dedicated expression on his face,” as she recalls in her memoir. A few months later, they met, by chance, at a party hosted by an elderly Maharajah, and within 4 years they were married. It’s hard to imagine just how controversial such a union would have been for a young white woman of Patricia’s social standing in the early 1940s. But against a noisy backdrop of protestation – from parents, relatives, friends, and colleagues – Patricia married Ayana, not out of defiance, but out of love. For the almost 3 decades that the two were together (they separated in 1970), the relationship remained intense and passionate – as well as sometimes turbulent.

READ MORE: Abbey Road had The Beatles, The Olympic had everyone else

Aside from their children (all of whom were “brilliant and beautiful,” as the author and journalist Reginald Massey writes; indeed, Chandrika, the youngest of four, was the first Asian model to appear in Vogue magazine), Patricia and Ayana’s greatest joint achievement was the Asian Music Circle, established in 1953. With the violinist Yehudi Menuhin as president, the AMC organised some of the first Western performances of musicians Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Vilayat Khan, Chatur Lal, and dancers Shanta Rao, Ram Gopal, Ritha Devi, and Sri Lankan Balasundari, and counted Benjamin Britten, the prima ballerina Beryl Grey, and the aristocratic Lady Harwood among its prestigious patrons.

“My father started organising shows and concerts for Indian musicians and dancers,” Chandrika tells me, “and, more often than not, they stayed in our house in Finchley. And he did have quite big stars coming over” – among them, the Indian yoga teacher, B.K.S Iyengar, whose practice is widely followed in the UK today. “[Iyengar] stayed with us in the house,” Chandrika recalls. “I don’t know how long he stayed there, but I remember he lived with us, because my mother used to have private [yoga] lessons with him. And I used to take part; I’ve got photos of myself standing on my head. Inside, we used to have them in our sitting room – we’d push back all the furniture – and when it was fine we’d do it in the garden.”

Over time, Chandrika’s father became notorious – “everybody knew him because he was one of the only people doing that kind of thing” – which is why, when George Harrison snapped a sitar string in 1965, it was Ayana who he called.

Before long, George and his wife Pattie had become regular dinner guests at the Angadis. “It was very ordinary and they were very nice,” Chandrika recalls. “They just felt quite comfortable and at ease.” Patricia painted their portrait, the Angadis and the Harrisons attended concerts together, and George and Pattie even invited the family to spend the day at their house in Esher. On one of these occasions, Chandrika remembers, “George played us the track of their new single, which was coming out, and asked what we thought of it because my eldest brother was very into music. And I think that was Paperback Writer.”

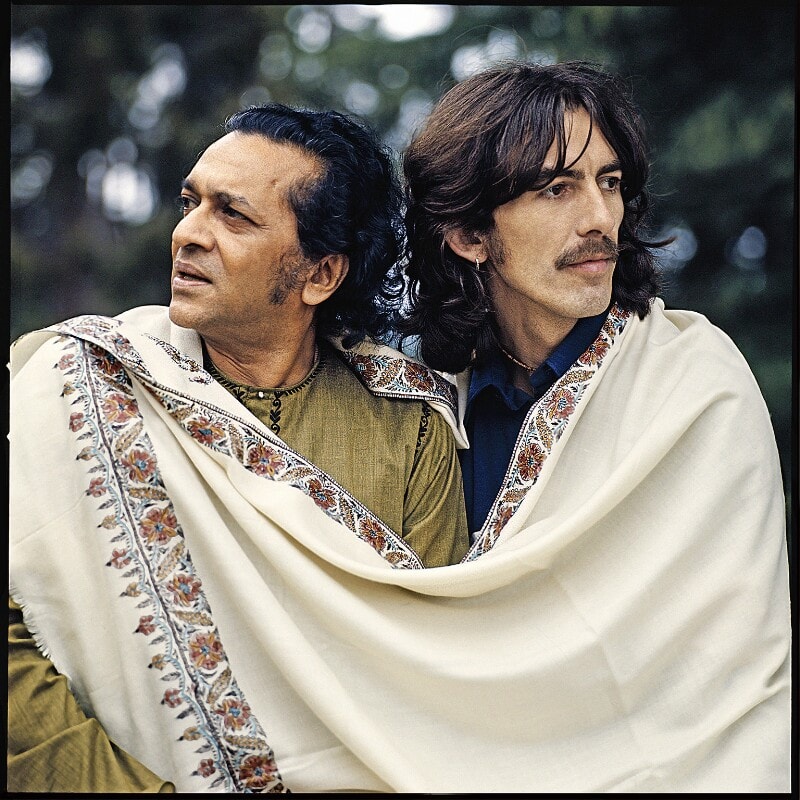

Chandrika was there on the famous night that George met Ravi Shankar at her parents’ home in Finchley. “I remember them standing opposite one another in our hall at the bottom of the stairs,” she says, “and George had brought his own sitar in a wooden case, and he was standing there, very casually, with one foot on the sitar case and Ravi Shankar said: ‘Well if you want me to teach you the sitar, the first thing I’ll teach you is to take your foot off the case.’”

Ravi Shankar and George Harrison

For Chandrika, however, the memory of Shankar that evening is dim – because that was also the night that Paul McCartney (destined, as the 13-year-old dreamed, to become her “future husband”) came for dinner. “I was too afraid to go into the sitting room, but in the end I decided to just make a dash for it and try to be dead casual. I saw a bowl of peanuts, so I took a fistful and crammed them into my mouth, and looked round for somewhere to sit. And the only free place was squeezed up on the sofa next to Paul McCartney. So I did it and then he started talking to me and my mouth was full of peanuts and I couldn’t reply. It was just painful.” Paul, however, was impeccable. “Talk about down to earth,” she says, “he was just so, so sweet. He was just lovely to me. And I was absolutely tongue-tied and horrendously in love.”

Eventually, the Harrisons and the Angadis lost touch – but the Angadis’ influence didn’t quite end there. Some years after the Shankar meeting, Patricia received an unexpected guest. “We answered the door to a young man dressed in saffron robes with a shaved head except for a pigtail emerging from the very top,” she recalls in the memoir. “He explained that he was a prophet from the sect called the Hari Krishna Community […] and did we know anyone who would be interested in helping them to set up a temple over here? I immediately thought of George Harrison, gave him the address and sent him on his way rejoicing.” No Patricia Angadi, no ‘My Sweet Lord’.

The story of the Angadis is a reminder of the fact that 60s popular culture didn’t spring from nowhere – and wasn’t as much of a radical break from the previous generation as we like to think. Without the influence of this suburban family, would we ever have had Revolver? Would the sound of the sitar have found its way into the pioneering pop music of the time?

Perhaps. And then again, perhaps not. Because this isn’t just the story of George Harrison’s meeting with Ravi Shankar; it’s also the story of an unconventional marriage that changed British culture. And though Ayana may have been the “daring” one, as Chandrika puts it – the one with the big ideas – without Patricia, it is unlikely that the AMC could have gone on as long, or as successfully, as it did. It was Patricia who supported her husband’s visions and whims, not only emotionally, and not only pragmatically, but financially too. In between teaching at a primary school and raising her adored children, it was Patricia who laid the table for the Harrisons, who painted their portrait (which they purchased from her years later), and who delighted them with her socialite charm (two years after McCartney came to dinner, he recognised Patricia while grocery shopping and introduced her to his fiancée Linda – such was the impression that she must have made).

We love to tell tales of bright, charismatic men, but in this story, it is Patricia – the curious and open-minded painter, mother, wife, novelist, teacher, socialite, and defiant child of Edwardian society – who stands out. “She was a remarkable woman,” Chandrika says. And who knows – British popular culture might not have been the same without her.