Winning awards is an obvious measure of success, but sometimes it’s the nomination that really matters. For Gwenno Saunders – who as an artist goes simply by Gwenno – that really was the case with her most recent album Tresor, which was among the 12 records nominated for this year’s Mercury Prize, pitting her against the likes of Harry Styles, Self Esteem and Sam Fender.

The prize on the night was ultimately awarded to Little Simz, for her blistering Sometimes I Might Be Introvert – and deservedly so. But Gwenno had already made history simply by being given the nod, with Tresor becoming the first album not predominantly sung in English to be nominated for the Mercury award.

Gwenno and I might have been sitting in a hotel café when we met, overlooking the picturesque beach at Poppit Sands in her native Wales, but in fact only one track on the record is in Welsh. The rest are sung in Cornish, a language which she learnt through her poet and linguist father.

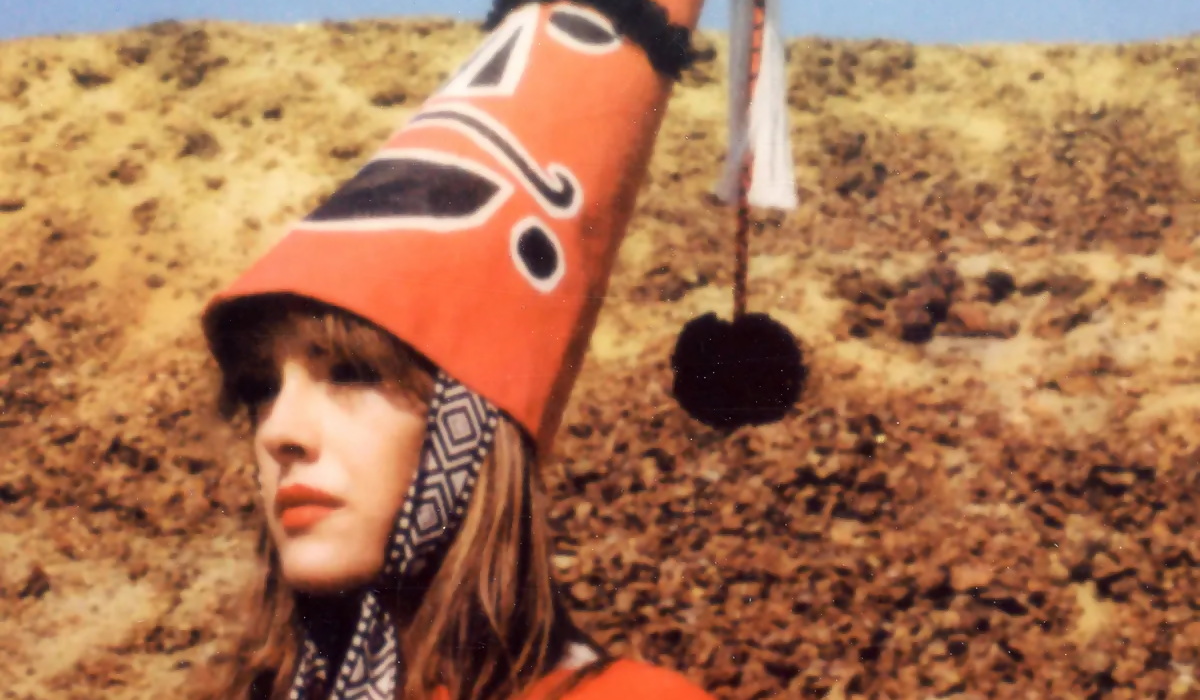

Gwenno at the recent Mercury Prize awards.

Gwenno’s history-making alone is one feat; achieving it predominantly in a language spoken by so few people is quite another. In fact, the latest ONS census figures from 2017 estimate that just 557 people in England and Wales declare it to be their main language. (Gwenno has played more than a small part in the language’s preservation. Her second album, and her first to be sung in Cornish, 2018’s Le Kov, is said to have contributed to a 15% increase in the number of people taking Cornish language exams during 2018).

And whilst Gwenno admits the Mercury nomination still “hasn’t sunk in at all”, her achievement is more indicative, she says, of “not having to make that linguistic compromise, when we live most of our lives in Welsh and Cornish. It’s been a great confirmation that we were right not to compromise from the beginning.

“I’ve got this weird blind faith in committing to what I think is right – I think that’s what you do as an artist. It’s always been about: if the music’s good enough, it doesn’t matter what the language is.”

That’s in no doubt. True to its name, Tresor, is a shimmering, at-times delicate assortment of ethereal psych-folk treasures. Like the beauty of the Cornish land, and its tales of fairies and mythology, there’s a hypnotic, almost immemorial aspect that reels you in.

Photo: Claire Marie Bailey

The opener, ‘An Stevel Nowydh’ (which translates as ‘The New Room’) is in fact all about a sense of displacement and the unknown, as she invites the listener into her home for a cup of tea, lulling them into a false sense of security, before asking, “Is the total lack of meaning an inevitable part of being?” Many an ear of course won’t be familiar with the meaning of the lyrics, but the sense of existential angst is there to ascertain regardless of language.

Titular track ‘Tresor’ has a plodding, equally otherworldly nature, whilst the likes of ‘Keltek’ and ‘Tonnow’ have a ghostliness that could fit on the latter stages of Radiohead’s The King of Limbs. The tranquil album closer, ‘Porth la’ also resembles a quiet gem, titled after the Cornish name for the seaside hamlet Gwenno wrote the album in – unlike Le Kov, which was written in her hometown of Cardiff.

“I guess I was interested [in recording Tresor in Cornwall] because I’d recorded the core of the previous album in Cardiff, imagining Cornwall,” she explains.

“I think I was really aware that the Cornwall I know has been through the home, through records and through stories – and people, because we’re very closely tied with the Cornish-speaking community in Cornwall, it’s a small community so you’re part of it.

“I just wanted to know how I’d feel being in Cornwall and trying to understand what my place is. I think the greatest thing when you’re an artist, is that it’s quite good to be an outsider; and I always will feel like one.

“That’s probably why I’m drawn to Cornwall because I know I’m not Cornish; so I’m always going to have an objective view of the place. It’s not somewhere I can say, ‘This is where I’m from’. I think that outsider perspective is quite important as an artist because you’re always observing things.”

“What’s funny, and I realise as I get older, is that all the people who don’t fit in anywhere else end up in music, because I think it’s a very forgiving place. As a community, I think it’s a very safe space for people to express their vulnerabilities.”

“The reason why I was drawn to music in the first place is because I felt like I would never quite get to the bottom of it; I knew I could never get bored of it because I would never know enough. I think that’s the biggest thing for me: that it’s a safe space for us all who don’t really fit in anywhere else.”

Such interrogation of worldly things has been a mainstay of Gwenno’s life, imbibed not least from her father’s artistic leanings, but also by her mother’s political activism, which was chiefly engaged in campaigning for the Welsh Language Society in the late-80s and early-90s – a cause that led to her being arrested twice. Not that such a thing shocks Gwenno.

“It’s so common. I like the shock value of it outside of Wales; people say, ‘My god, that’s terrible’, but actually it’s so common in Wales. There’re not many people I know who haven’t been arrested for campaigning for the Welsh language and many of them have been to prison as well. Much longer than my mum – who only went for two weeks,” she adds, chuckling.

“For me, that’s what’s interesting with the Welsh language, really, is that the context of it has been so politicised because it’s been oppressed, historically. And also, music has reflected that. A lot of Welsh-language music has been made to express its political value.

“That’s the Welsh language landscape, and it’s what you draw from when you’re thinking and writing in Welsh – you instinctively think about social issues and political issues. That’s how I feel anyway.”

It’s expressed on Tresor, too. The one track on the album that isn’t sung in Cornish is ‘N.Y.C.A.W.’, an acronym for Nid yw Cymru ar Werth, which translates as ‘Wales is not for Sale’.

Perhaps expectedly, given the song’s political message, its tone is one of the more assertive moments on the album, with its titular message amplifying the disdain for the amount of second homes bought in Wales, mostly by people in England. This not only massively increases property prices but also leaves some villages as ghost towns for large parts of the year.

“The track isn’t tongue-in-cheek”, though, Gwenno outlines. “It’s just a look at, ‘What does this slogan mean to us?’ And beyond us shouting it and thinking about second homes, how complicit are we in this massive neo-liberalist project, as individuals? In Wales, where is the balance between taking responsibility over the society that we create and the lack of control we have over that society? Because we don’t control our own affairs.”

Yet despite some of the grievances still being levelled between the England-Wales border, when it comes to music, Gwenno speaks of “a really exciting time for Welsh music”. When we meet, it’s amidst the commendable cross-cultural Other Voices festival in Cardigan, which makes a point about putting on Welsh-speaking artists.

One artist on the same billing as Gwenno particularly excites her: rapper Sage Todz, who spits in English and Welsh and has recently reworked the patriotic ‘O Hyd’ song as a hype song for Wales’ forthcoming World Cup ambitions.

“I think he’s so talented. I saw him perform at the Welsh Music Prize [where Gwenno has previously won Best Album, for her 2015 debut, Y Dydd Olaf]. Obviously, I’ve seen the viral videos of [Sage] as well.”

“There’s a big change with Welsh-language music. I feel like in this past three or four years, it’s widening. That’s what happens with Welsh language music; you think everything’s become samey, then all of a sudden new people come in and have a different take and use the language in different ways.”

And just as it’s an exciting time on a broad level for Gwenno’s native tongue, so too is it a time of change for her and her music collaborator and husband Rhys, with their second child due in February. (Firstborn Nico gets his own spot on his mother’s Mercury-nominated album, contributing a handclap on the album’s titular track).

Gwenno performing at Other Voices festival in Cardigan.

“When you’re a mum,” Gwenno says, “you’re aware of the windows. So my window is now until February for any feeling of time on my own, which you need to write; you need space to think, consider.

“For me, it’s been so integral to my creativity that I’ve continued to create as a parent. And my circumstances have been such that I can – because I know it’s not easy for everybody. I think writing music is so part of who I am, that it’s really important I’m able to do it because I think if I didn’t, I’m not sure what would happen,” she chuckles once more.

For those wondering, Nico speaks Cornish too (as indeed Gwenno’s expecting child will) – something that has created a special bond between grandson and Gwenno’s Cornish-speaking father.

“My dad has never put any pressure on me regarding the Cornish language, ever. He’s never been strict at all; he’s just used it. But he did [once] say, ‘Well, if you don’t use a language, it dies’. He said it quite casually,” she gently laughs again. “I thought, ‘There’s only around 500 people [who speak Cornish], I should probably do something about that.’”

She certainly has done something. In fact, as the first Mercury-nominated artist for a non-English album, she’s a record-maker in more ways than one.