This week, Netflix has premiered a new show centred on serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer and will premiere Blonde, the fictionalised Marilyn Monroe biopic, next week. We look at whether these works are grossly exploitative or if they have value as pure entertainment.

It’s only been a few days since Netflix premiered their newest true crime related series: Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, and there’s already been accounts that people have had to turn it off because it’s so disturbing.

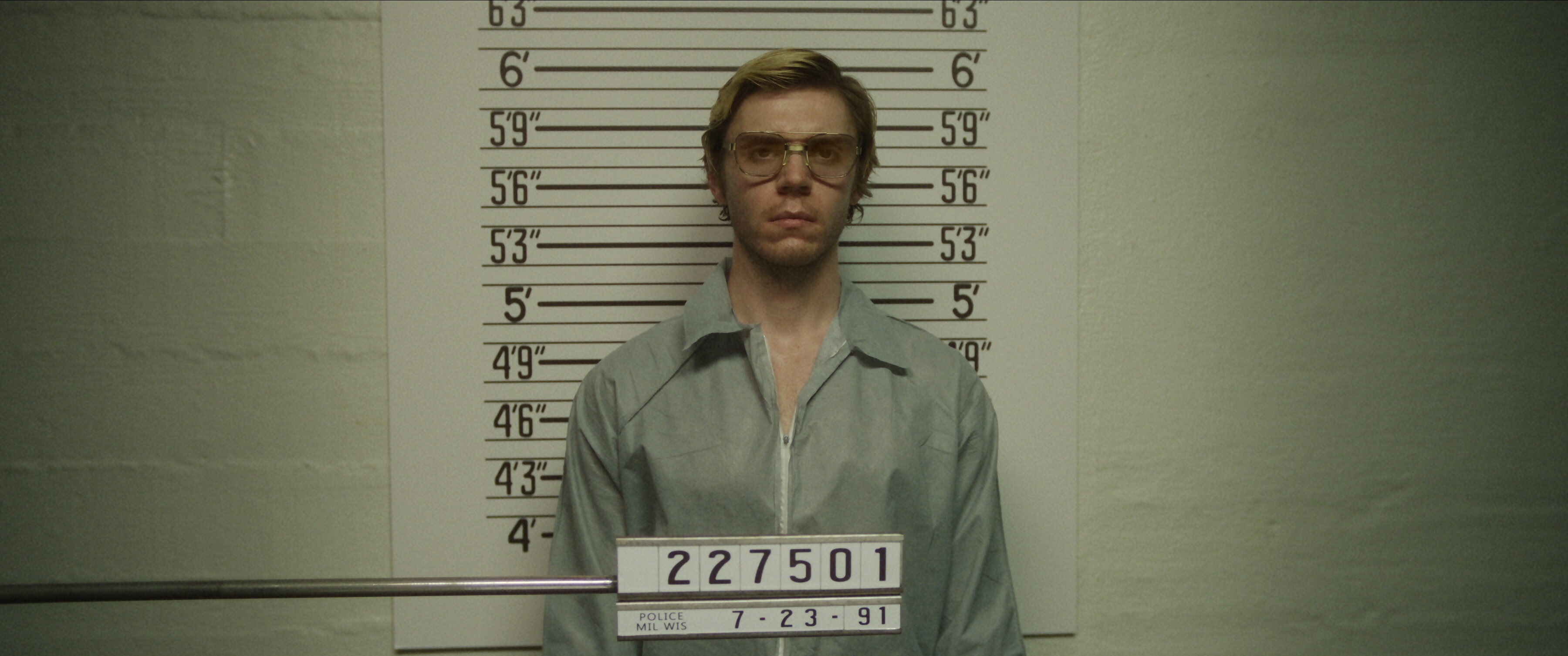

A relative of one of Dahmer’s real life victims has also taken to social media to say Netflix’s show has re-traumatised them. In Ryan Murphy’s take on the infamous serial killer, Evan Peters plays Dahmer, but how healthy is it to keep bringing back a notorious murderer on screens big and small?

I’m not telling anyone what to watch, I know true crime media is huge rn, but if you’re actually curious about the victims, my family (the Isbell’s) are pissed about this show. It’s retraumatizing over and over again, and for what? How many movies/shows/documentaries do we need? https://t.co/CRQjXWAvjx

— eric. (@ericthulhu) September 22, 2022

On the other side of the coin is Blonde, Andrew Dominik’s Marilyn Monroe film which received its world premiere at Venice Film Festival. The reviews have been mixed and even before anyone had seen the film, there was a lot of talk about the film’s NC-17 rating. According to reports, Blonde features very graphic scenes, including a POV shot of Monroe’s vagina.

Ana De Armas as Marilyn Monroe in Blonde. Credit: Netflix

Both Blonde and Dahmer have been accused of being exploitative, making cheap entertainment of real life tragedies. As it often is with these things, the victims of the circumstances have no voice whatsoever, no real influence over how these events and the people are portrayed.

Of course, both Blonde and Dahmer are works of fiction. These are not documentaries and creative liberties have been taken. Blonde is based on a novel by Joyce Carol Oates, but Ana De Armas’ spookily accurate depiction of Marilyn has already been noted. She seems to nail her breathless voice, her delicacy and her sex appeal, effortlessly depicting the starlet’s inner life.

But there is also something distinctively gross about how Marilyn has been portrayed and her story is once again being told by men, feasted on by vultures who are looking to make a quick buck. Sure, Blonde can probably have some artistic value but what exactly are we gaining from it? Does it say anything new about Marilyn by fictionalising, dramatising and scandalising her story?

Similarly with Dahmer, why are we lifting up a serial killer? Why are we giving him the Hollywood treatment? Everyone knows Jeffrey Dahmer but how many of his victims can you name? Would you recognise their faces? Probably not.

Evan Peters as Jeffrey Dahmer. Credit: Netflix

Netflix notes that Blonde is a “reimagining” of Marilyn and it’s not the first time a director has wanted to change history. Tarantino went as far as saving Sharon Tate, who died tragically at the hands of the Manson cult, in Once A Upon A Time…In Hollywood in a strange case of a hero complex.

Same goes for Ryan Murphy’s Hollywood. The series, which depicts Hollywood as the face of progression, mixes fact with fiction in a dizzying manner and it’s sometimes hard to tell what’s real and what’s not. It’s a self-congratulatory attempt at seeming progressive, rather than actually examining history as it happened.

Who are these shows and films for? They’re clearly not interested in providing us with facts, otherwise they would be documentaries. History is filled with problematic fiction films skewing the facts of real life events.

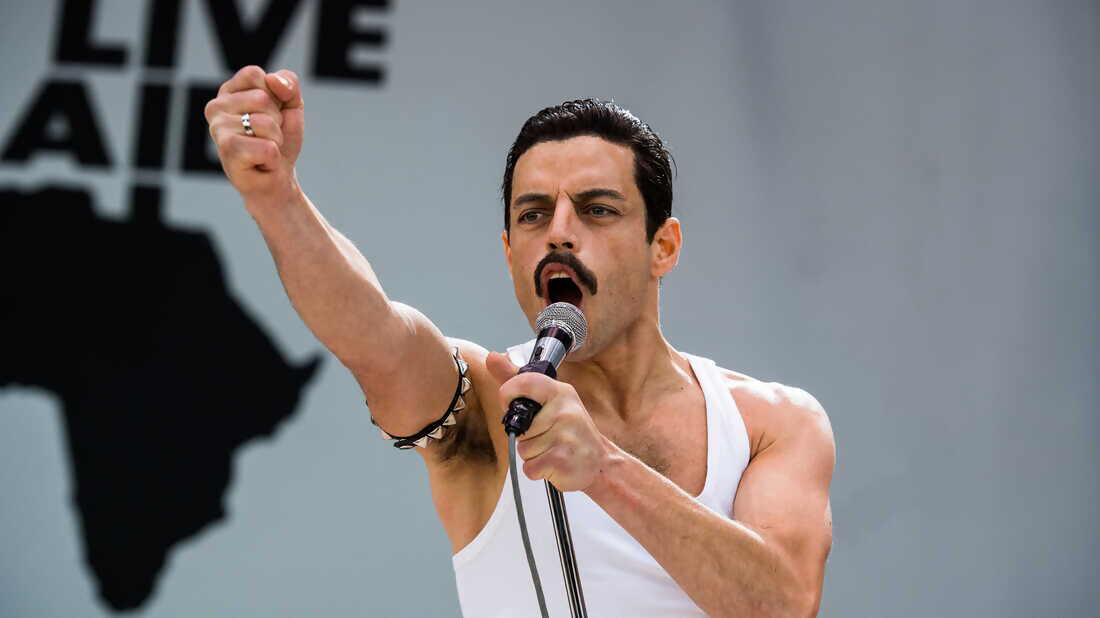

Take the Oscar-winning Bohemian Rhapsody for example. Controversial director Bryan Singer (accused of abuse, but that’s a different article) and screenwriters Anthony McCarten change the timeline of events to push a deeply problematic agenda.

Rami Malek won an Oscar for his portrayal of Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody. Credit: 20th Century Fox

While we can’t be absolutely certain of when exactly Freddie Mercury learned he was HIV positive, it’s widely accepted this was after the famous Live Aid concert. Singer’s film however frames his HIV as a punishment for Mercury’s party days and homosexuality and Live Aid as a way for him to redeem himself.

It’s this strange rearrangement of facts that makes Bohemian Rhapsody so bad. Dramatising something is one thing, lying about it and passing fiction as fact is another. While both Blonde and Dahmer are clearly works of fiction, their value and their entire existence is something we should challenge and question.

This isn’t to say we shouldn’t make fiction films about true stories. There are plenty of ones that are worthy and gracefully handled, such as All The President’s Men, The Social Network (which also fictionalises events heavily, but tells a larger story of betrayal in the digital age) and Spotlight.

It’s more a question of who we are highlighting in history and who gets to tell these stories. History doesn’t belong to anyone, but personal histories belong to those affected by the events and fictionalising something like Jeffrey Dahmer is bound to bring pain to the families of the victims.

Andrew Dominik’s Blonde has proven to be controversial. Credit: Netflix

Marilyn Monroe was notoriously exploited by the industry and it seems like Blonde is a particularly egregious attempt to profit from her and control her image, especially after Kim Kardashian wore Marilyn’s custom-made dress to the Met Gala.

Again I ask, what do we gain from these fictionalised accounts? Blonde may well be the best film of the year in terms of artistry and de Armas’ performance, but maybe it’s time to ask ourselves why we’re so drawn to these real-life tragedies? Out of all the millions of inspiring stories out there, maybe we could focus on the ones that deserve to be showcased and lifted up.