“In theory every possible and impossible image is there, if you find the right pixel combination.”

Why do you think AI art is taking off now? Is it cultural or down to technological advances?

Technology has made it possible. It’s something people have wanted to do for a long time. There was this technological leap six or seven years ago that was so efficient it crept into everything. Once it became possible to do visual work with it, it got more attention.

Technology has made [AI art] possible. It’s something people have wanted to do for a long time.

You’ve been interested in this for a long time. I read you wanted to test bitmaps…

That’s what got me started very early on: the idea that the digital image is a window to every possible image. The problem is finding them. Initially, I was naïve and thought I just need to run through all the possible combinations and I’d find interesting stuff. Of course that’s not how it works, but in theory every possible and impossible image is there, if you find the right pixel combination.

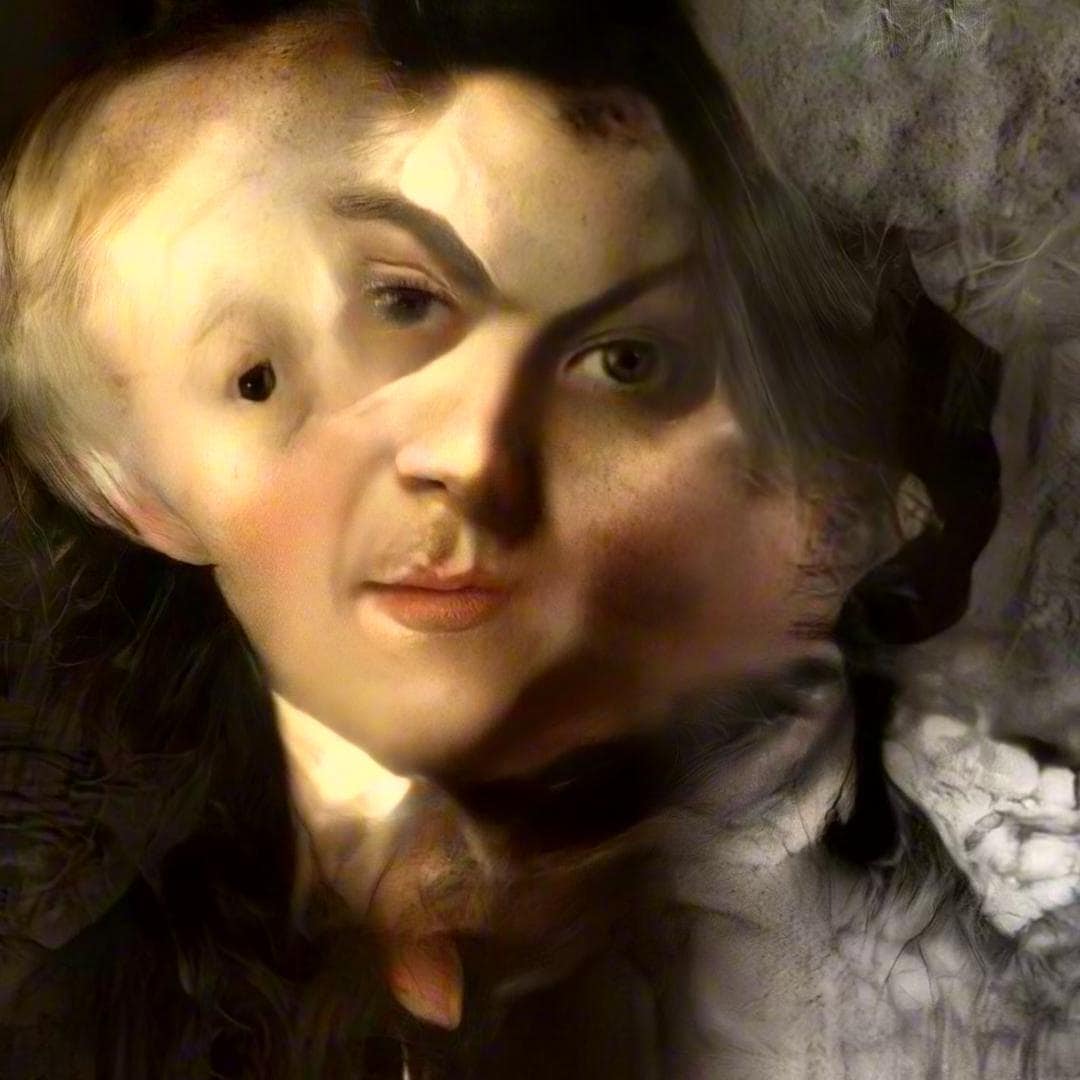

Portrait of Mario Klingemann

You’ve talked about ‘interestingness’ and ‘the uncanny’ as concepts. Do you think these are tied together?

They are. Interestingness is about how we process information. We want to get something that captures our attention. There is an element we already know, then something unusual comes in – a hole in our path, for example. That’s interesting. It’s not beautiful. It’s just not meant to be there.

Interestingness is about how we process information. We want to get something that captures our attention.

When you talk about glitches, it’s an error, and allows you to break out of standard expectations. Most glitches eventually become uninteresting because they have the same effect, so again you try to find those which break the unexpected in a new way. You learn the distribution of randomness; you realise it’s always happening within this expected range and it makes it uninteresting again.

When you work do you see abstract data, or are you looking toward the final aesthetic?

The data is a way to get the real world into my art. Synthetic data is limiting. I believe since we live in the world most of the data should have some relation to this.

The criticism of AI art has often been that it’s just pushing a button. Your argument has been that data is like a pigment for the artist.

Definitely. It’s not that much different than analogue artists or authors. You go through the world. You collect impressions. You see situations. You write them down. A painter takes a slice of that. We make our own essence from those impressions. For me this is very legitimate and it’s not just pressing the space bar. It takes away some mechanical processes. It’s not the same as painting, but there are some elements in how I approach my art that’ssimilar to how painters go about their work.

‘Memories of Passersby I’ by Mario Klingemann

Your work seems to be about occupying transitional spaces, and latent space seems to be transitional. Is that somewhere you’re comfortable?

I believe the interesting stuff happens at the edges. There’s always something between two fields that gets negotiated. That’s how art works for me. Taking several different concepts and plugging them together. In the end I approach it like a big collage.

I believe the interesting stuff happens at the edges. There’s always something between two fields that gets negotiated. That’s how art works for me.

Your recent work Circuit Training at the Barbican was interacting with the audience.

It gave a glimpse of a possible future where humans were used for three tasks: data source, Mechanical Turk, and consumer. The machine collects your likeness, the photo studio tries to capture as much of you as possible, then uses that data to train models in a random way.

‘Hanging Man’ by Mario Klingemann

People look at what the machine created and judge if they like it. In response the machine tries to make more of the stuff people want, and in the end presents images people like most. It tries to steal your time. Attention and interestingness directly translates into lifetime. You give a little bit of your lifetime to the machine.

And was it well received?

Yes, the feedback has been good. So far it has collected half a million images, so people have definitely been interacting with it.

Are you seeing this type of AI work being made in London?

There’s a huge AI scene in London, people like Jake Elves, who’s very close to what I’m doing, but taking it from the queer angle, Anna Ridler, and Luba Elliot who organises a creative AI meetup. From all the people I admire and respect in the AI scene 40% are from London. London is a hotbed for AI art.