★★★★★

Above: Dressing for the Carnival (1877)

Touring many modern-day galleries, one will be forgiven for feeling dispirited at the lengthy artist ‘abstracts’ – the ‘rationale’ treatment accompanying the exhibition. Sometimes its contents are indispensable to understanding the artist’s motivations and ambitions, but often it’s beleaguering nonsense hiding poor quality ‘art’.

Winslow Homer was an artist who didn’t allow for such silliness. His viewers would have to make do with what was on the canvas or paper rather than what a curator or Homer himself would supply afterwards. Because to do so with Homer would be to insult.

The best introductory example is in regards to ‘Promenade On The Beach’ (1880), in which two sprucely ladies gaze out to sea under a threatening blue-grey sky. A collector asked Homer to explain. ‘The Girls are “somebody in particular”…’ he wrote back, ‘…and I can vouch for their good moral character. They are looking at anything you wish to have them look at, but it must be something at sea & a very proper object for Girls to be interested in. The Schooner is a Gloucester fisherman. Hoping this makes everything clear.’ As you can tell, Homer did not like to explain his works.

Promenade On The Beach (1880)

Born in 1836 in Boston, Massachusetts, Winslow Homer’s 74-year lifespan witnessed an era of civil and scientific upheaval across the United States and the West that his paintings couldn’t ignore, even after having spent several traumatic years as a war illustrator during the American Civil War. We’re here confronted with a gifted American realist who confidently combines a talent for observation with pure imagination when setting out to depict the scenes of his time.

It was this domestic conflict, pitting abolitionist northern states, united beneath the Union Flag, against anti-abolitionist Confederate states, where the mild-mannered but hungry Winslow Homer had his artistic baptism of fire – his training up to this point had been from his mother, also a gifted watercolour artist, and his tenure in education and as a commercial illustrator. In this National Gallery and UK first, we’re invited to view all of this American master’s work in one place on British soil. The Civil War conflict is introduced as the exhibition’s first theme upon entry.

Sharpshooter (1863)

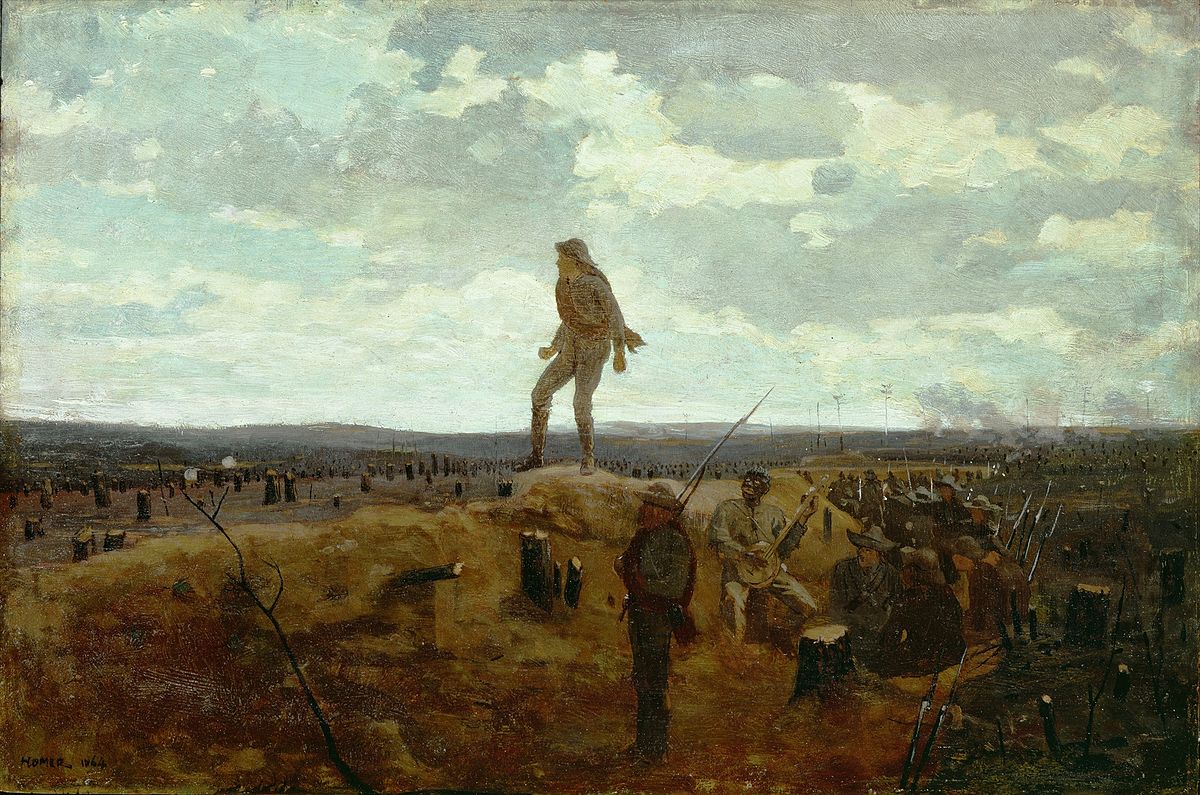

Defiance: Inviting A Shot Before Petersburg (1864)

On the left, positioned very cleverly opposite its antagonising Confederate opponent pictured inside a separate frame on its right, is ‘Sharpshooter’ (1863). A Union Army sniper is poised atop a Virginia tree branch with his rifle aimed dead ahead, pointing to the right of the frame. The long-distance weapon was a new invention, harnessing modern technology that allowed soldiers to pick off targets a mile away from the action. The invisibility of these men often drove their enemies, holed up behind trenches and earthen defences, mad with anxiety. Homer later told of his immediate impressions of the weapons he’d seen in his 20s on the field of battle: “I looked through one of their rifles once . . . [the] impression struck me as being as near murder as anything I ever could think of in connection with the army & I always had a horror of that branch of the service.”

The Confederate soldier in the frame next to the Union Army sniper in ‘Defiance: Inviting A Shot Before Petersburg’ (1864) is incandescent with rage (or perhaps insanity provoked by the panopticon-like phenomenon of the undetectable sniper?). He mounts the battlement with a roar, as if challenging his well-equipped opposite number to a fight on equal terms and closer quarters.

Prisoners of the Front (1866)

The exhibition then proceeds to mirror Homer’s life and artistic progression as we’re shown harmonious but uncertain scenes of children playing in fields, sons accompanying a father on a boat trip, likely off the Atlantic coast in Prouts Neck, Maine, where Homer summered later in his life.

Homer’s attention to African-American and Afro-Caribbean culture, and its resilient character in the aftermath of a war that was fought predominantly over their freedom, is remarkable for its atypicality. Very few artists at the time even portrayed black Americans, let alone treated the plight of the newly freed men, women, and children with this amount of sincerity.

What remains here in a British gallery in 2022, long after Homer’s death but in an age where problematic race relations still hamstring North American civil cohesion, are essential documents of a displaced people suddenly handed agency but with an enormous effort still ahead (indeed, agency in some form only – the ensuing segregation laws capped many of the newly freed African-American’s freedoms).

We’re invited to trace Winslow’s steps to his ancestral homeland: England. The beaches, bays, harbours and locks of Northumberland are where Homer spent two happy years depicting the defiant, unshakeable natives who appeared to have become part of the storms that had battered them for centuries.

Inside The Bar (1883)

They are hardy people, especially the women. Tall, muscular, and statuesque figures with babies slung across their backs return the storm’s roar and sea’s spray with a ready, knowing stare. A standout example is ‘Inside The Bar’ (1883), which Homer made on his return to the States in New York, but it depicts a North Sea fisherwoman.

Whilst I questioned the curator’s daring proclamation that Winslow Homer is not only the best American watercolourist but the best watercolourist ever, eclipsing J.M.W. Turner, this exhibition does demand superlatives. However, at times it feels like the paintings have been organised and displayed in alignment with the issues of our age.

On climate change ‘Channel Bass’ (1904) allegedly shows Homer ahead of his time depicting the damage industrialised societies are having on our natural environment – in this case, sealife – despite there being a long tradition of anti-modernist sentiment in the Anglo-Saxon West in which he belonged, not least amongst Blake and the lesser British Romantics.

The Gulf Stream (1899; reworked by 1906)

On colonialism and race relations, it’s suggested that Homer is sympathetic to the forcibly-created African diasporas of the US and the Caribbean but that he also objectifies them.

On scientific advancement and naturalism, when observing the quiet, watery post-hunt scene in ‘Hound and Hunter’ (1892), we’re supplied the context that Darwin’s On The Origin of the Species was causing ripples amongst the leisurely literate classes, but not what Homer’s musings on theology were. Granted, there’s minimal biographical footprint of the reclusive New Englander, but an equated suggestion like the ones in no short supply next to paintings depicting the Civil War, its aftermath, and black Caribbeans at sea, would have been helpful. Like almost every American of British heritage at the time, Homer’s parents were Protestants, and their son would have had a deep and profound belief in the soul’s continued journey after death.

Northeaster (1895)

The final room contains Homer’s late-career paintings, ones increasingly influenced by his awareness of the fragility of our species and the coming end of his life. Very few human subjects are to be found; indeed, it’s made clear some were purposefully omitted later by his hand. Instead, we see crashing seascapes, silent mountainous vistas, and unforgiving and hostile wintry hillsides.

The chaos is intriguingly relatable to Leonardo Da Vinci’s late-life ‘deluge’ drawings, in which he obsessed over portraying infernal explosions and enormous blocks of collapsing matter. In this display, we too get to see – prematurely for many viewers like myself – the reflections and focus of an elderly spectator of life. It’s a window into your own future and an essential experience gallery-goers should not deprive themselves of.