As hip-hop celebrates half a century, Normski’s photographs offer a time capsule of its indelible impact on the UK’s cultural tapestry. He tells us all about when Ice Cube showed him around his mum’s house, casually interviewing Queen Latifah a thousand feet above New York, and asking De La Soul to pose with daisies.

If there’s one name synonymous with the layered and winding evolution of UK street culture, it’s Normski. A staple in the hip-hop and acid-house scenes, Normski rode the wave of almost every burgeoning Black youth movement in Britain from the early 80s onwards.

The Man With The Golden Shutter wasn’t just a photographer; he was a part of the zeitgeist, presenting documentaries and hosting the seminal programme Dance Energy on BBC Radio 1, which would eventually go on to grace TV screens nationwide.

As hip-hop celebrates its 50th birthday this year, Normski’s images serve to remind us of the power of this genre to push boundaries and continuously elevate culture. It’s a genre that transcended its birthplace in America to shape youth culture worldwide, across all races. And Normski was at the centre of that as the tide swept into the UK and Europe.

His new book, Normski: The Man With The Golden Shutter, adds a new cornerstone to his legacy. Published by ACC Art Books, it’s both a memoir and an era’s photo album, cataloguing candid shots and offering recollections that take us back to a time of intense energy, improvisation, and creativity.

But it’s not merely nostalgia. Each frame charters the journey through subcultures, genres, and generations, explaining how we got to where we are now through shot and story, all with Normski’s enthusiastic dedication to detail. These photos remind us that the people behind the lens aren’t always just chroniclers of cultural history; sometimes they make it too.

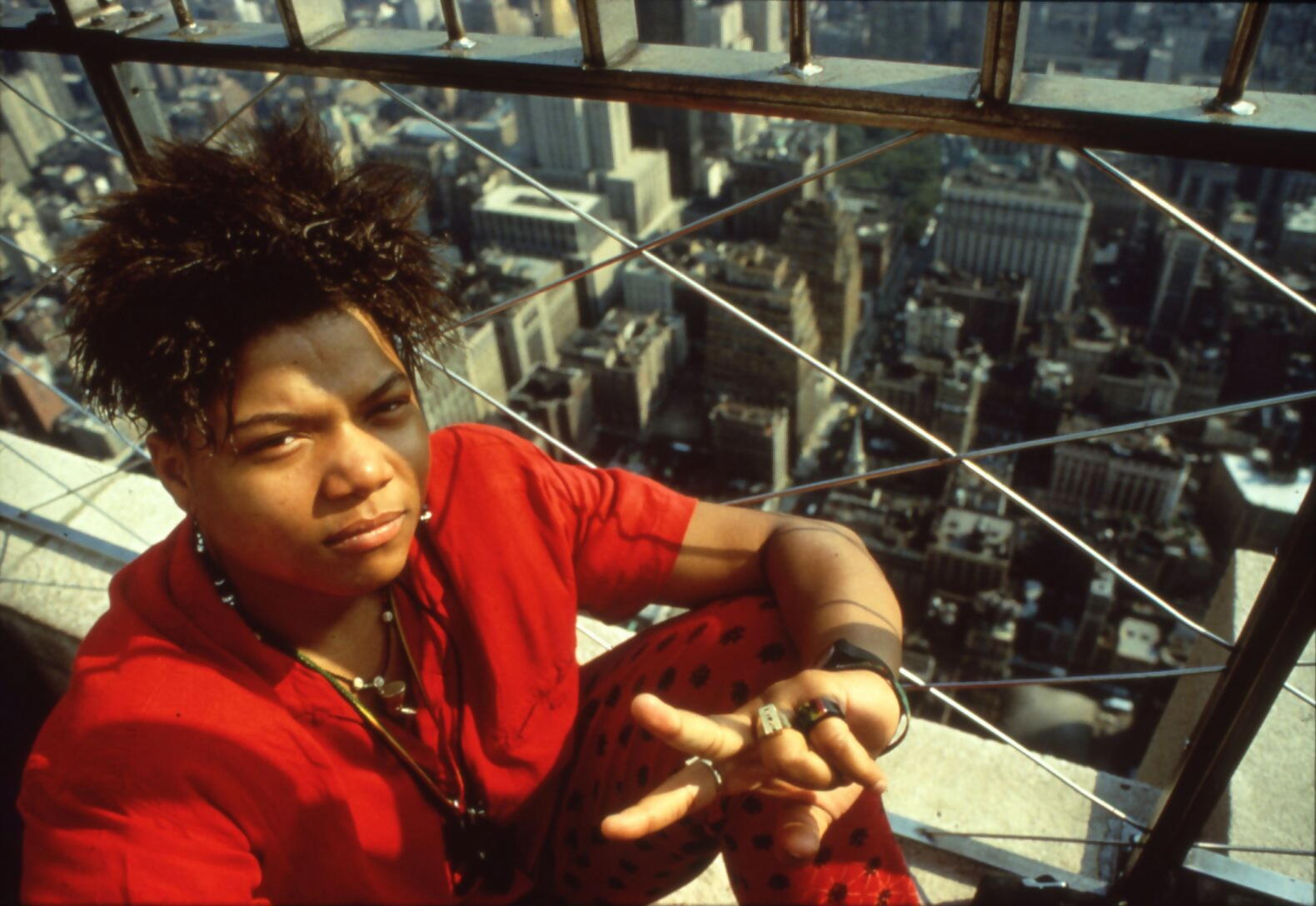

Queen Latifah

Queen Latifah atop the Empire State Building in New York City, 1980s (Copyright: Normski)

“We were at the New Music Seminar in New York in the late 1980s, which was like being an Olympic team abroad, we were literally representing the UK. The Queen Latifah shoot came about because Chris Hunt, who was the editor at Hip-Hop Connection magazine, had made me his leading contributing photographer. There were others, of course, but I had this ferocity of just going everywhere and photographing everything, which lead to me having a two-page feature column at the beginning of the magazine called The Man With the Golden Shutter – which is where the name of my book came from!

“Queen Latifah asked me, “Wouldn’t it be really cool to do the interview and photoshoot at the top of the Empire State Building?” and I replied, “Yeah! Brilliant idea, I’m well up for that!”. The idea was that, from a journalistic point of view, we needed to separate the artist from the madness of the seminar, so where do you go, to a quiet corner of a deli somewhere or another similarly quiet place? Not everyone goes to the top of the Empire State Building and even Queen Latifah said after we stepped out of the lift, “YO! This is really cool!” What none of us had thought about was how windy it gets up there so there was a moment or two when her hair was flying all over the place, but I’m hoping I’ve used the one where her hair looks good! But it was all part of the challenge of the shoot! I always try my hardest to try and have nobody but my subject in the frame so there’s no distraction to the eyeline.

“So much happened in such a short space of time. It’s amazing. Then it became very commercial and popular, and then we had the direction changing to more gang-related stuff. That lovely golden era of culture, no swearing, and the funky element, just transformed into something else, really. But there you go, it’s another generation coming in! Different narratives, different perspectives.”

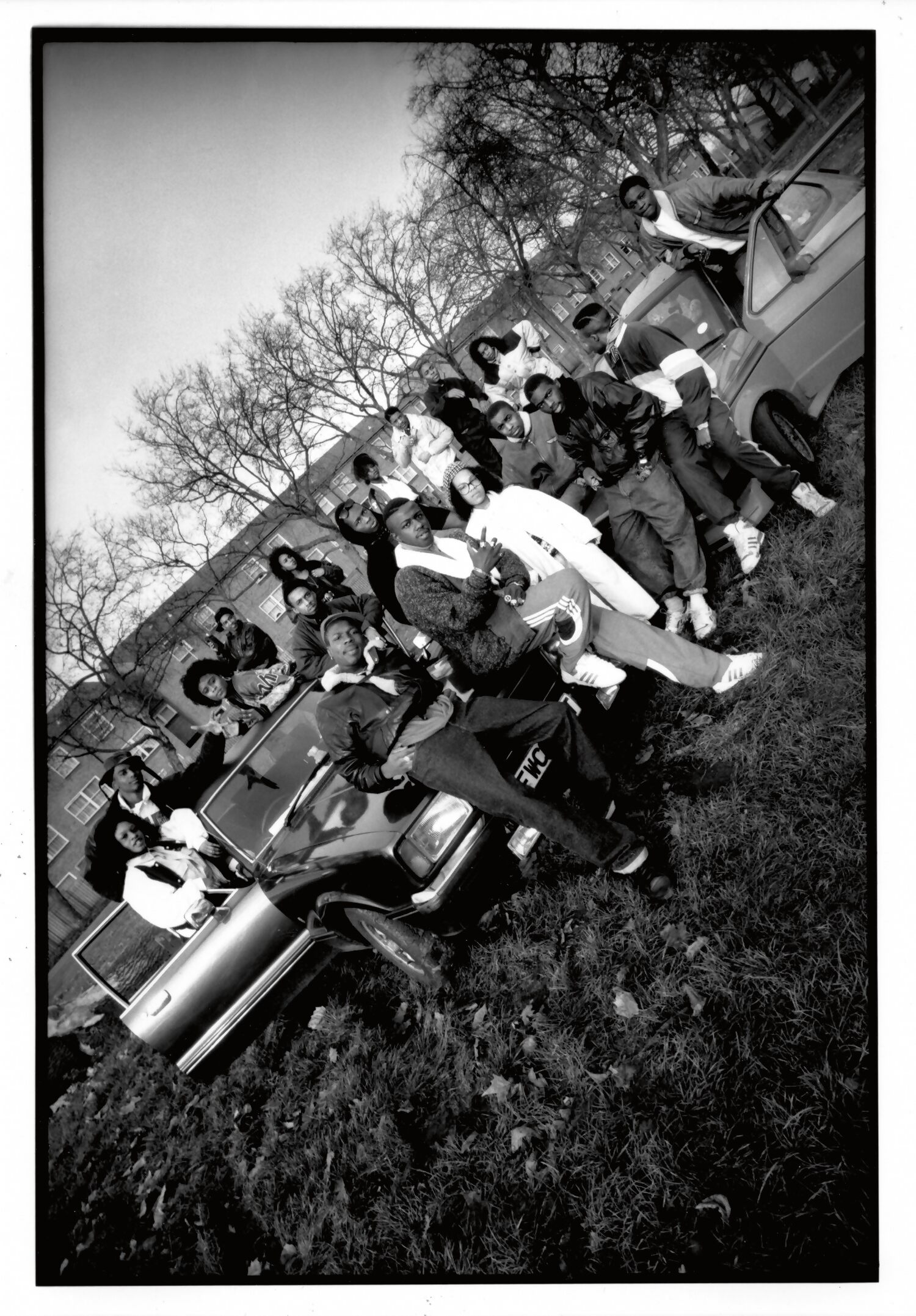

Overlord X and posse

Overlord X and his crew (Copyright: Normski)

“Overlord X’s music was so way ahead of everyone else. It was wicked. I always had this ‘reportage’ style of being sent to a photoshoot on-site, like I was working for a newspaper. We’d agreed over the phone to do the shoot in Victoria Park. I remember having an A to Z in the car, coming in from Camden, where I grew up and lived and making my way to East London, to this place called ‘Victoria Park’.

“I parked up and walked into the park to find these guys. I’d said to them to bring all their mates if they wanted to have them in the photo. It wasn’t hard to spot them because they all drove their cars into the park. I was freaking out, always going by the rules, and they said, “Look, don’t you worry about that.”

READ MORE: Michel Haddi | From Paris orphanage to photographing Tupac, Bowie, and Debbie Harry

“It was like he’d brought the whole block of flats! I love that because it’s true to them, it shows where they’re from, the cars they drove: A Ford Fiesta Mark I, I think, a Ford Grenada – these were the cars back in the day!

“I was lucky. I had the perfect reason to meet and get to know people from all over. When I first came East, I think the furthest was Brick Lane. I didn’t like any of it. It was just too many bricks and concrete for me. Camden’s got green all over it. So it was a big deal to finally have a reason to explore these places. When I first went to South London, it was to photograph Saxon Posse, and that’s what people always used to remember: that guy Normski, you didn’t really know where he was from, but he seemed to be everywhere! And that’s because the scene was so spread out.

“One of the things that gives me great joy is that I didn’t actually have a studio. Before I started studio work, I was self-taught to create a location environment anywhere, to create a studio outdoors.”

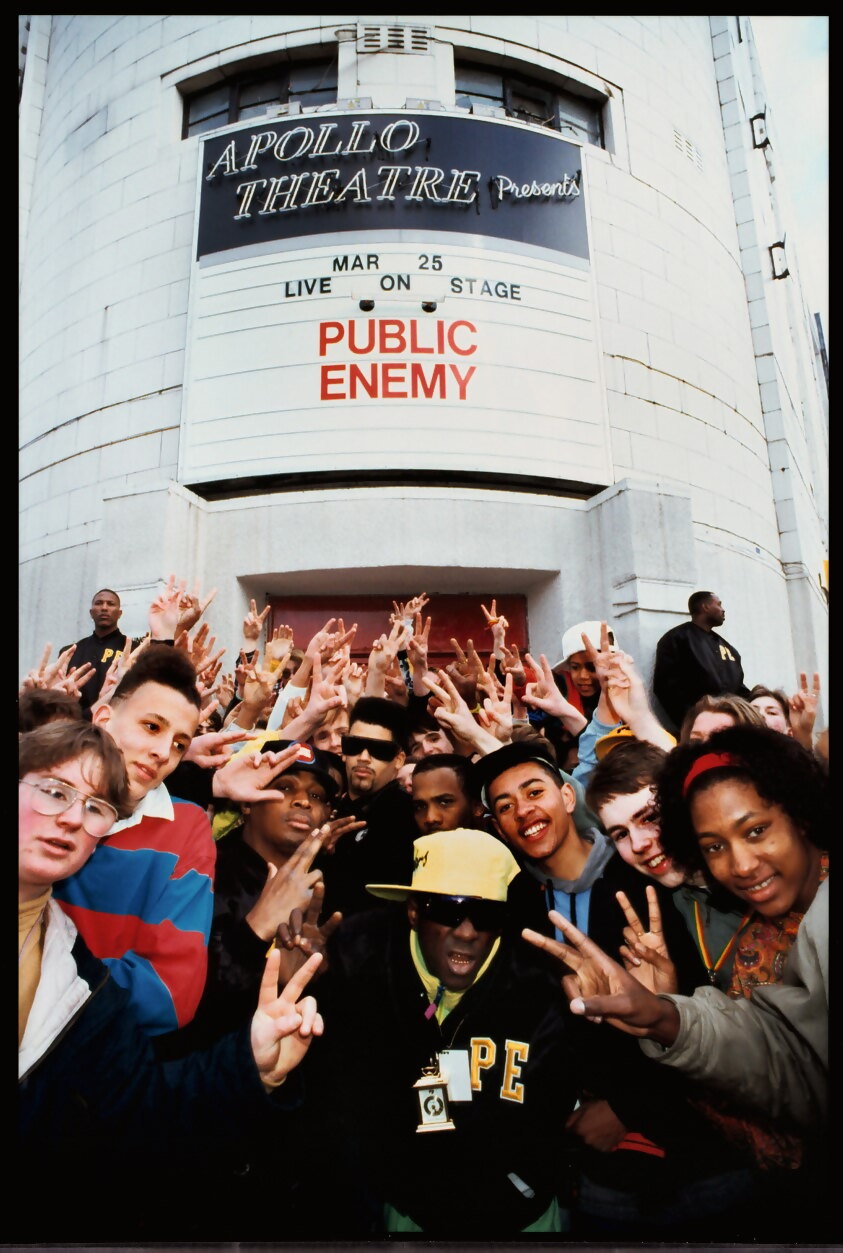

Public Enemy

Public Enemy outside the Manchester Apollo (Copyright: Normski)

“Malu Halasa and I went up to Manchester very early one morning to meet the guys on their tour bus to do a shoot and interview…and they were fast asleep. We didn’t realise that they were on different timezones, travelling, gigging late into the night. Malu stepped onto the tour bus, and one of them said, “No, no, everyone’s asleep, we can’t do anything right now” and she just replied, “Well, that can’t happen.”

“So Malu Halasa walked right up the tour bus, woke Chuck D up (she knows him, and she’d met him before), and he got up and stepped off the bus with a tired Flava Flav and the other guys. Malu told him we needed to take the photos now, and he flat-out refused until she said it was Normski who’ll be taking the photos. Chuck D said, “Normski? Okay we’ll get up for him.”

“And then, in the end, one of the photos from that shoot ended up being on the single sleeve for the UK release of ‘Brothers Gonna Work It Out’. They did like a ‘poster pack’, which included a soft focus photo of them I’d taken. I’ll never forget it. I had no idea I’d one day have a photograph of mine licensed to be the cover of a Public Enemy single.

“That was in 1988. When things like that happen – BOOM! No wonder Rankin loved my work. He was also part of the young London scene, and he was like, “Damn, you’re definitely getting the work, Normski!””

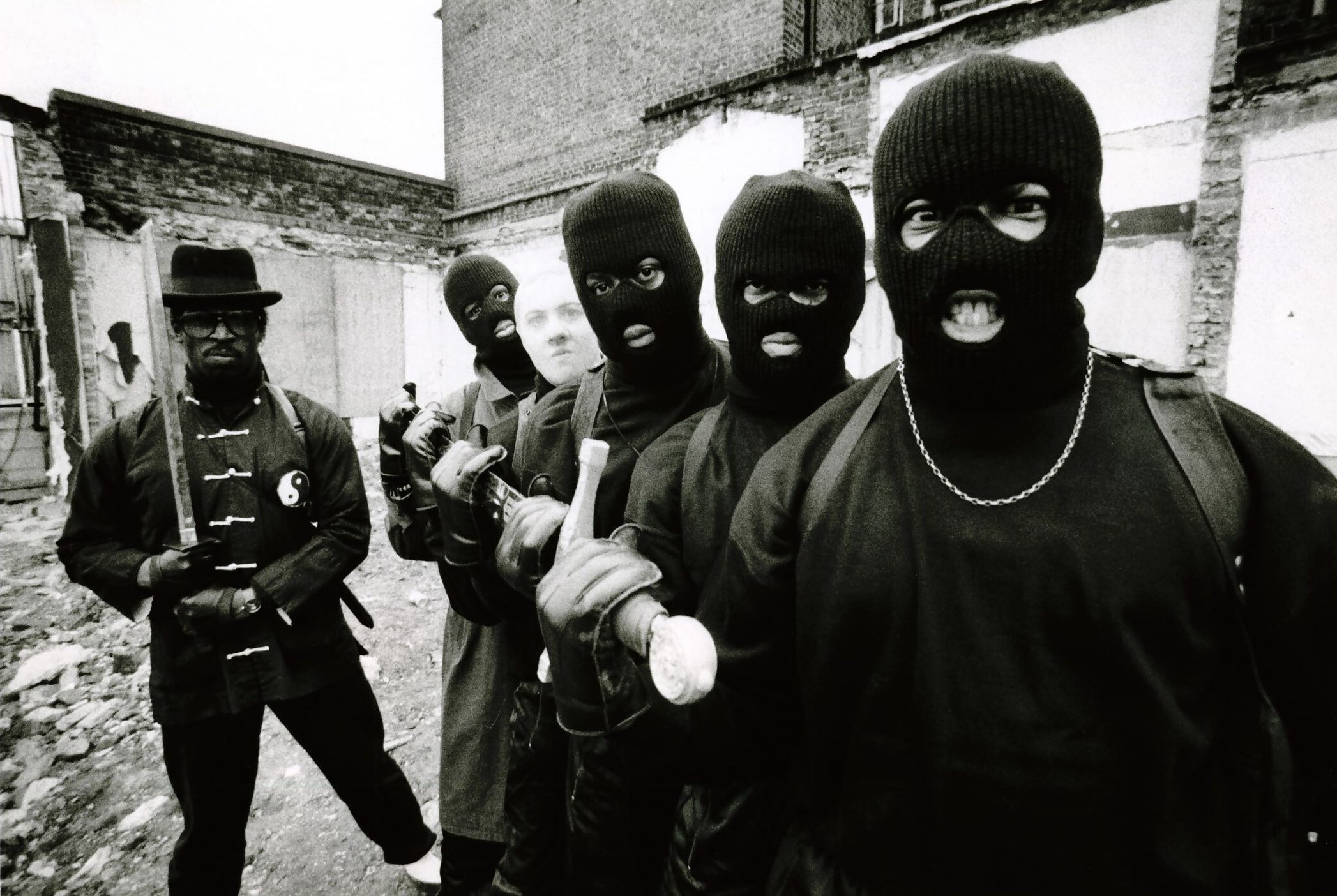

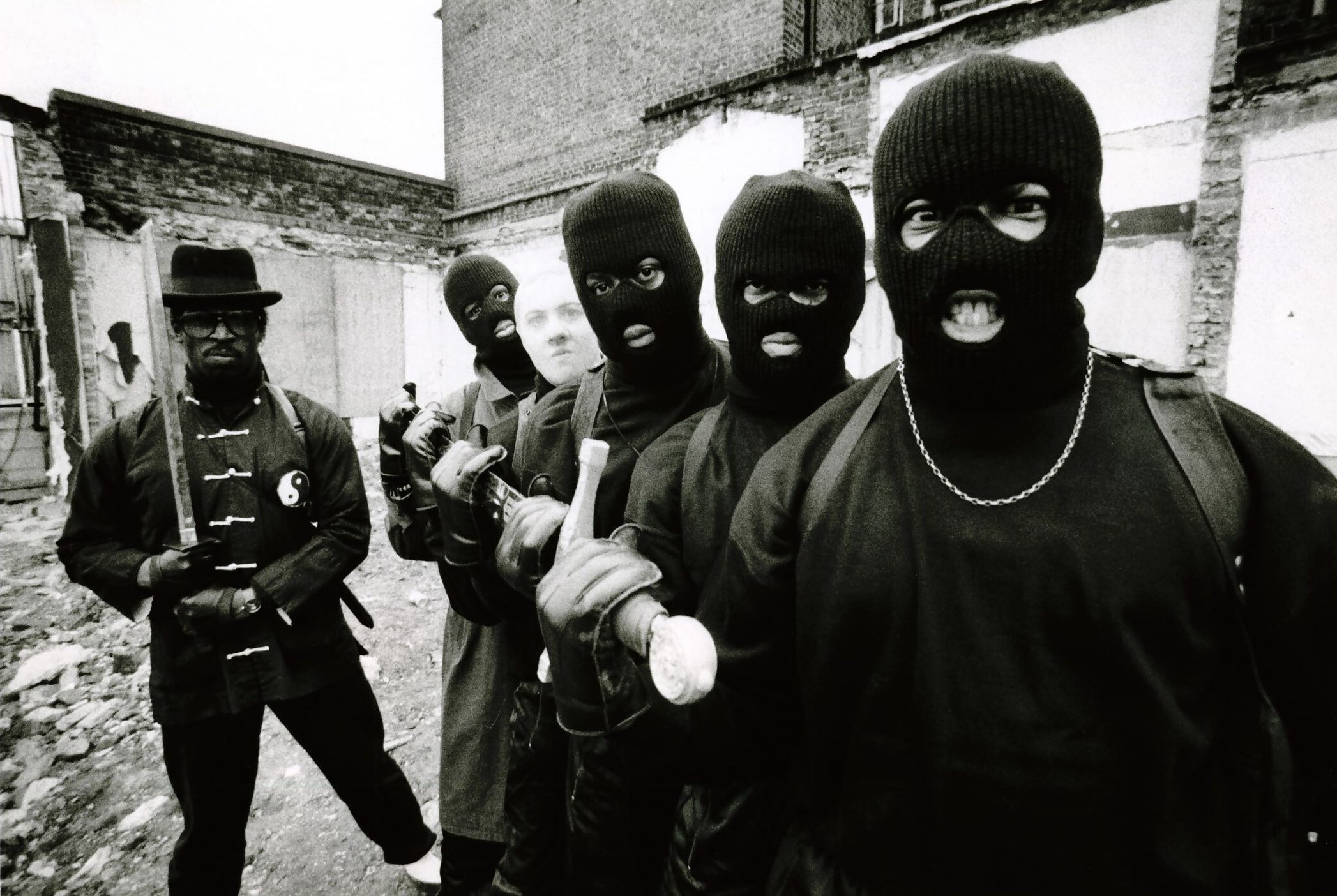

Hijack

Hijack, photographed in 1989 (Copyright: Normski)

“I was very brave to take that picture. Nobody was taking photographs of Hijack because I don’t think anyone was gonna go anywhere near ‘em! And I don’t think they wanted anybody anywhere near them, either! Ulysses, one of the rappers, was a kung fu master. The whole thing about them was this yin and yang element and the fact they had a white brother in the crew and mixed-race brothers.

“I was born in 66; kung fu movies were a big deal for us in the late 70s and early 80s. Everyone wanted to be Bruce Lee, bruv, trust me. We’d grown up with that. So it doesn’t surprise me that you’d have the Wu-Tang Clan in America as well as a bit of that here, but earlier. But Hijack were bringing MORE than just kung fu, they were pretending to be bank robbers as well! They were all about intimidation. As a rap group, they wanted to hijack the whole situation; we’re talking about some next-level stuff.

“When we were doing that shoot, we were in a bit of derelict wasteland and had to climb over a few walls but were spotted by the police! They said, “What they hell’s going on here?!” and I said we were doing a photo shoot for a record. So they said, “Right, well hurry up, and do what you’re doing, because you can’t really be carrying swords around.” You wouldn’t be able to get away with anything like that nowadays because of knife crime. It’d be deemed to be in very bad taste. As much as you might think it’s cool waving a knife or a sword like that around in your video, that’s going to remind a whole heap of parents that they lost their child.

“In the end, this particular shot was banned when it was used because the IRA were quite active, and there were major similarities. Anything that looked like that would have been seen as being in bad taste. So they got cancelled straight away. Ice T then picked them up, with Rhyme Syndicate Records, and they went out to America and did a reshoot, but that was the last record they ever did.”

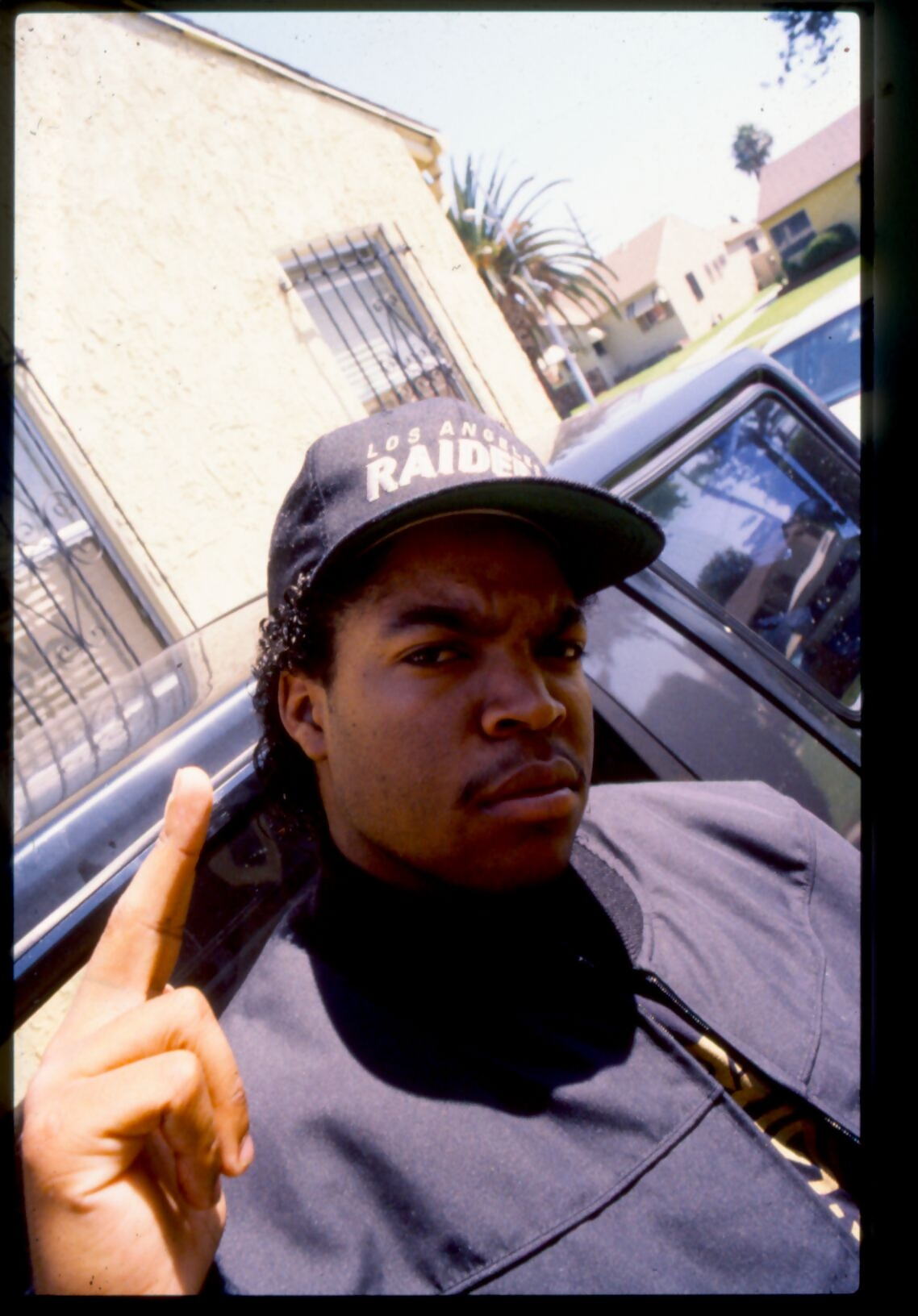

Ice Cube

Ice Cube outside his mother’s house in Inglewood, California, following his split from rap group NWA (Copyright: Normski)

“I’ll be honest with you: being Black has been my meal ticket in life, because I realised there are people like me all over the world. And just because someone’s got a different accent, doesn’t make them much different. When I first flew out to LA, I was more comfortable there than the whole production team I was with. I was the presenter for a documentary about the history of hip-hop, and one of the artists we were interviewing was Ice Cube.

“Before we did that, I got to take intimate photographs of him. He’d just broken up with NWA and was living at his mother’s house, and he wanted to make sure that we knew how he was living. So, we get there, and we’re like, Fuck, this guy’s such a big rapper, but he’s still living at home with his mum. Of course, now we know why: he’d been ripped off and hadn’t been paid. We’ve all seen the film. We all know the story.

“It was a beautiful thing. He invited me and the producer, Sharon Ali, into his house. His mum wasn’t there at the time, but he also seemed to want to show us how he was really living. He showed us his bedroom, and he wouldn’t allow me to take any photographs inside at all: at that point he was still on the FBI register.

“He showed me his 10-track Portastudio cassette mixer (I had a 4-track one back home in London), and he had music and books everywhere; it was more of a cluttered boy’s room than mine! Being inside Ice Cube’s bedroom was a big reality kick for me. It was a nice enough house, but he literally just had a little room upstairs. Single bed. Normal guy.

“He took us back outside and showed us the bullet holes from where someone had shot a gun and left a bullet hole in the window. That had upset him more than anything: “My mom’s house, man. They even took a shot at my mom’s house.” And that’s where I took the photo. You can see he’s got a little bit of an attitude on him. It was very special, and I wasn’t daunted at all in any way.”

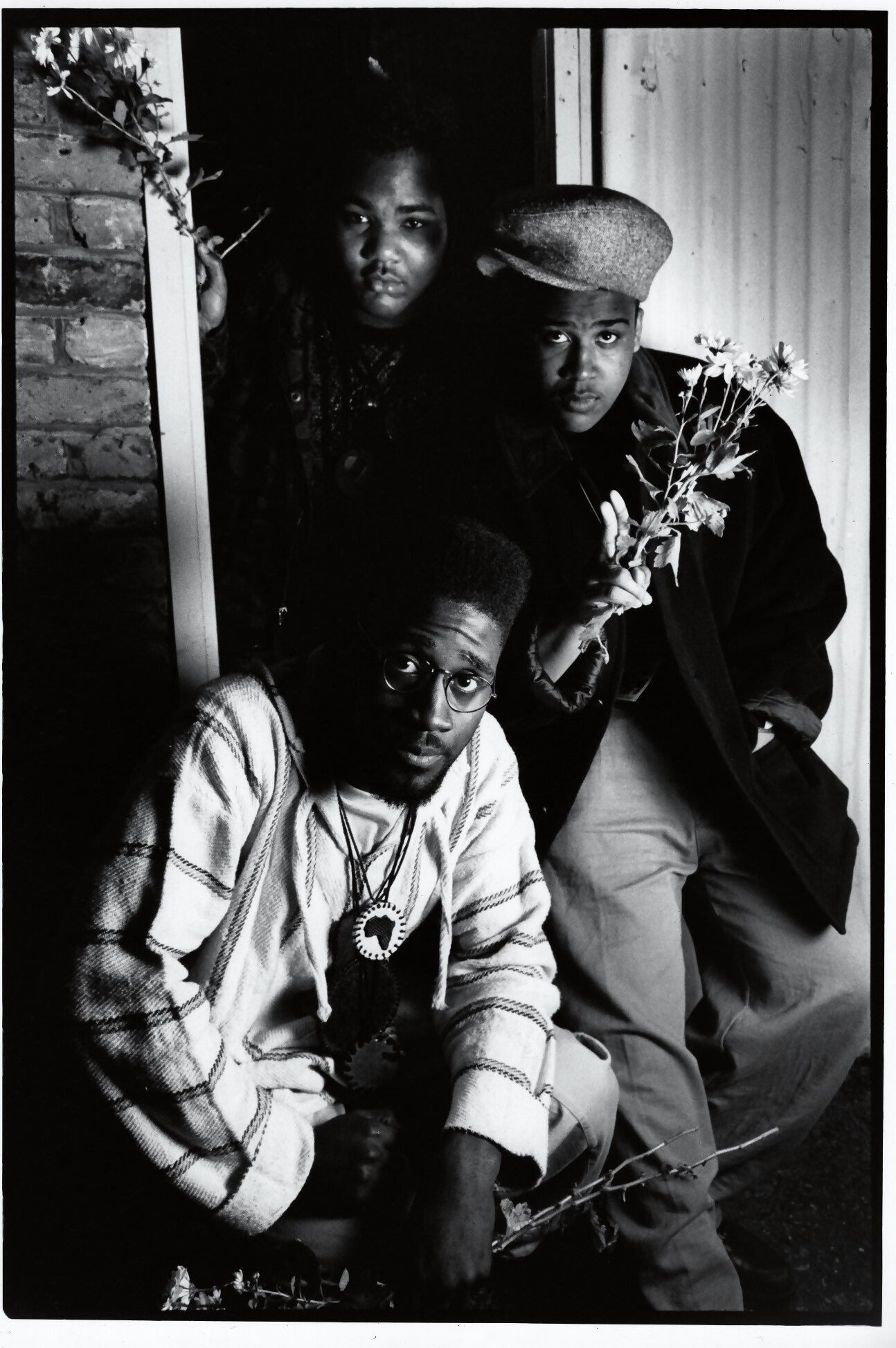

De La Soul

De La Soul in Brixton, 1989 (Copyright: Normski)

“My girlfriend at the time suggested earlier in the day that I take some flowers to the shoot. I was like, “Are you mad?!” but she said, “Because of the Daisy Age!”. I thought long and hard about it because I thought I can’t be walking around with daisies! But then I just went for it. I went all the way to Brixton with a bunch of daisies I’d bought from a flower stall at the market.

“So I did some shots with De La Soul, and then I pulled out the daisies and asked if they wouldn’t mind holding them. They were really confused, but I insisted, “You’re the Daisy Age rappers!” They all looked at each other and said, “You know what? That’s kinda cool. Okay!” No one had ever done that with them before. It was all part of their album artwork and everything, but they hadn’t been photographed with flowers. What I love about photography is when you take something out of its normal setting and do it differently.

“The crucial thing to understand about hip-hop at this time is that none of us were completely sure about what we were about. We were all finding out together. I hope there’s that innocence and naivety that we felt coming through the photos.”

Want to write about music? Pitch us your ideas.

Are you passionate about music and have a story or hot take to share? whynow wants to hear from you. Send your music-focused pitch to editors@whynow.co.uk. Let’s make some noise together.