Issey Miyake’s troubled beginnings propelled him to ‘bring beauty and joy’ to the world of fashion, Margaux Daly writes.

“In Japanese we have three words: yofuku, which means Western clothing; wafuku, which means Japanese clothing; and fuku, which means clothing. Fuku can also mean good fortune, a kind of happiness. People ask me what I do. I don’t say yofuku or wafuku. I say I make happiness.”

Issey Miyake was seven years old when his eyes rested on a scene of horror so surreal, so dreamlike, it was unparalleled to anything his ancestors could have witnessed. In 1945, the little boy’s entire life was decimated, explosively, by the most deadly weapon mankind had ever made: the atomic bomb. And so, one of Hiroshima’s most famous sons joined in with the rest of his compatriots in the miserable, painful, and determined reconstruction that followed.

Except Miyake-kun was not miserable. The bomb and its aftershock may well have sealed the fate of several important figures among the young Issey’s friends and family, including his mother, whilst leaving him with a lifelong limp, but these were memories he knew he would never escape from. Instead, he trod a path toward brighter times, as he preferred to think of ‘things that can be created, not destroyed, and that bring beauty and joy’.

Belonging to the postwar generation that rebuilt Japan, Miyake believed “design has the power to change lives by enhancing them, offering solutions to contemporary problems, and bringing joy.” This belief emerged for Miyake when he first saw the decorative handrails on two bridges made by sculptor Isamu Noguchi called Tsukuru (‘To build’) and Yuku (‘To depart’), unveiled in 1952 as part of the city’s postwar transformation into a ‘City of Peace’.

An overview of Hiroshima in autumn of 1945

Inspired by the pictures inside his sister’s French and American fashion magazines (carefully read away from the eye of his army officer father), Miyake began illustrating his own designs. Given no avenues to study fashion design at home, Miyake left Japan in 1965 to immerse himself in the alien world of Parisienne haute couture, studying at École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisisenne, apprenticing under Guy Laroche and later Hubert de Givenchy. He struggled to see his place in fashion’s high society, inspired rather by the 1968 student riots where he “witnessed first-hand the beginning of a new era: the era of the common man”.

Armored with a new sense of confidence as a fashion society outsider, Miyake returned to Japan to open Miyake Design Studio in 1970, where he flourished in departing from the conventional social groups and approved aesthetics of Europe’s fashion scene. He began his lifelong exploration in monozukuri (‘way of making’), searching for ways to create something new using technologies that honoured traditions of the past.

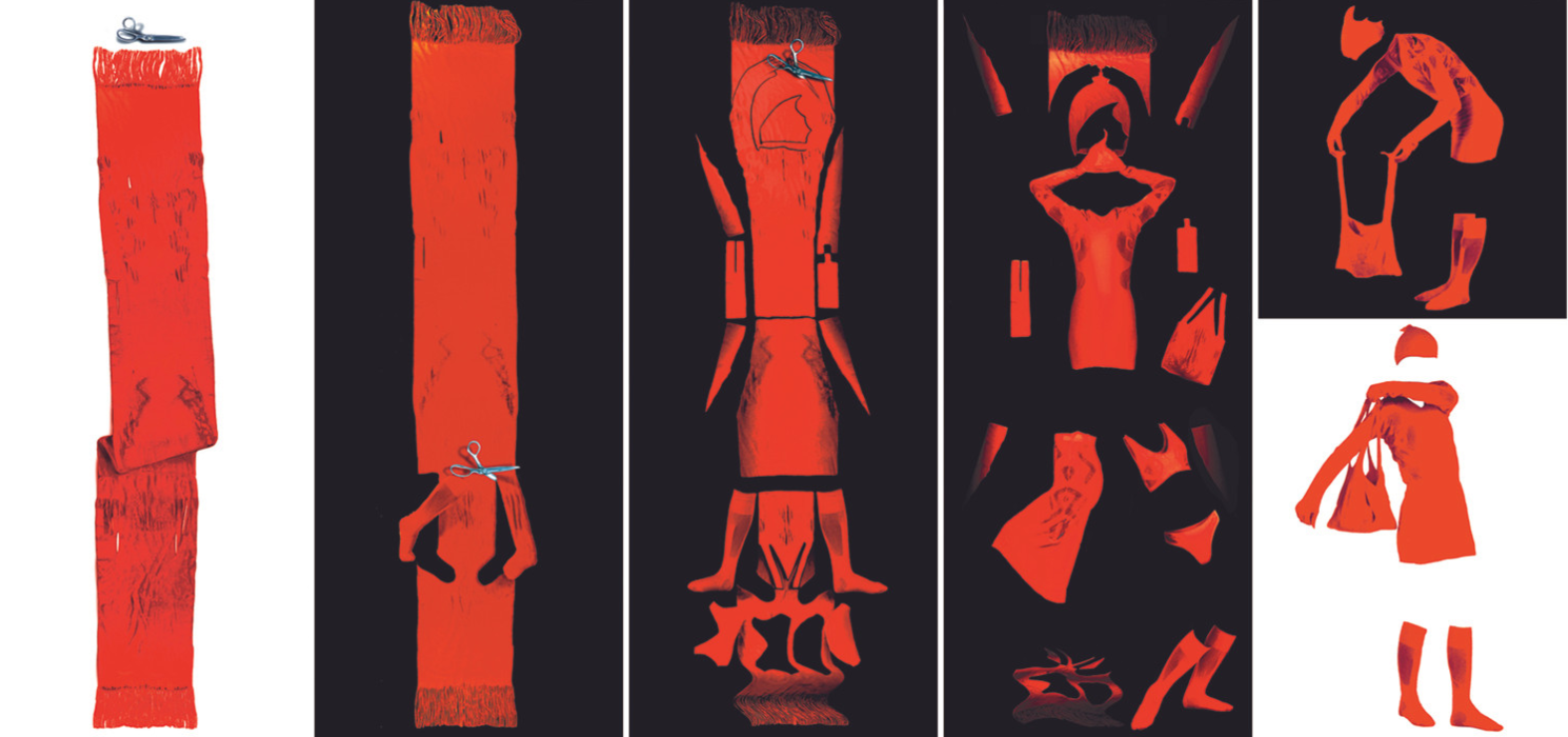

Issey Miyake, Fujiwara Dai, A-POC Queen Textile, 1997

‘Issey Miyake’, his iconic namesake label, showed its inaugural collection in New York in 1971. The show caught such buzz it was performed six times to accommodate all 6,000 attendees. By Autumn/Winter 1973, Miyake secured his place in Paris Fashion Week, showing biannually to this day. His designs won unmatched respect both commercially (netting $50 million in worldwide sales in 1983), and in high-art circles.

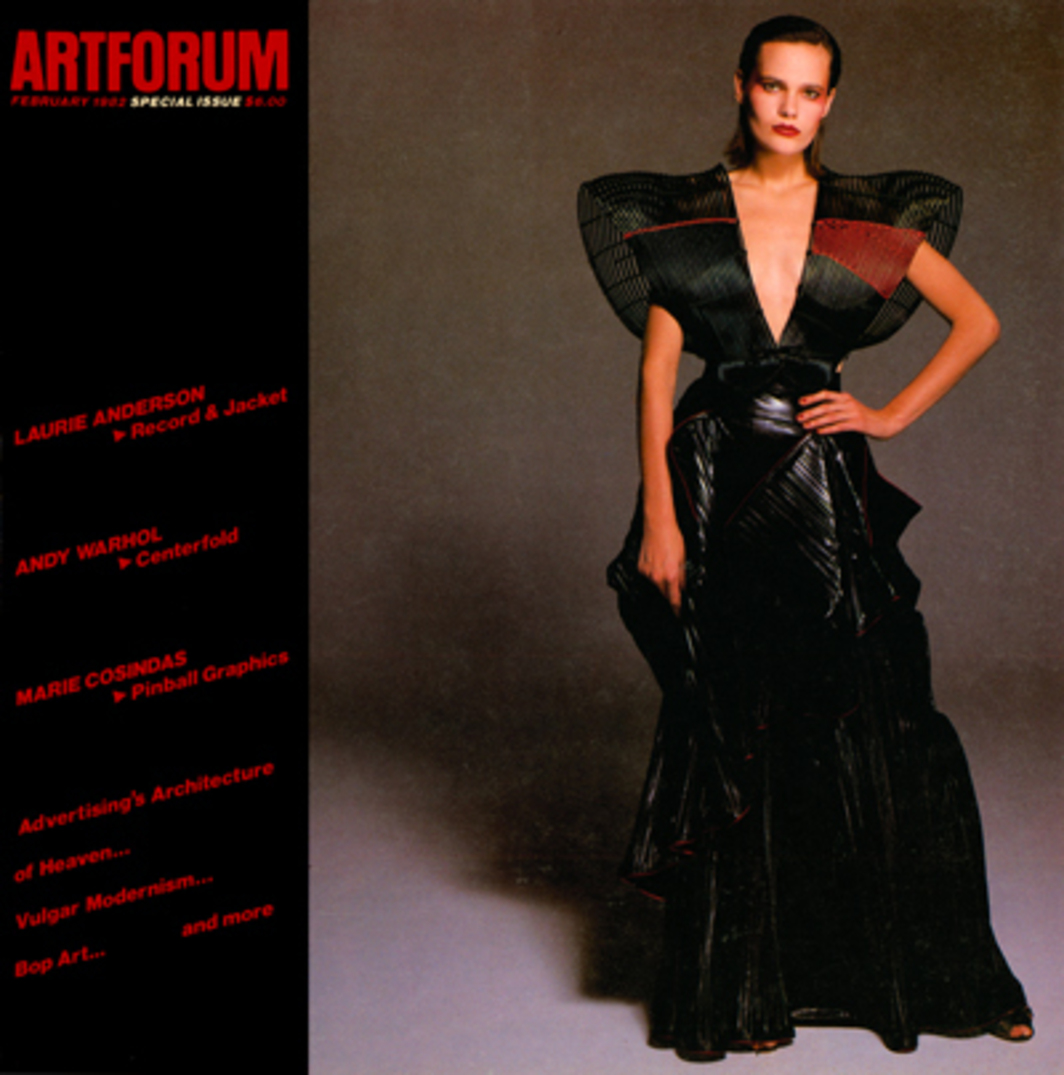

His gown, made of rattan vines, appeared on the cover of Artforum magazine in 1982. Miyake pointed out, not without pride, that “it was unheard of for a piece of clothing to be featured in an art magazine”. The achievement was a precursor to when, in 2005, a Miyake piece became the first to be held in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Miyake’s design on the cover of the February 1982 edition of Artforum magazine

Pleats Please on a Paris runway in November 1994. (Credit: Yoshikazu)

Miyake’s signature pleated designs were first realised when he was commissioned to make costumes for the Frankfurt Ballet in 1991. In a revolutionary act, he cut oversized garments from cloth, folded them into origami-like structures, slipped them between sheets of paper, and pressed them at high heat. The resultant garments featured permanently pressed pleats that bounce with body as it moves. His studio eventually featured its own pleating machines, which could be customised to produce endless possibilities of voluminous, textured designs under the spin-off label ‘Pleats Please Issey Miyake’, launched in 1993.

Issey Miyake in Paris in 1998 (Credit: Denis Dailleux)

In 1998, Miyake launched A-POC (A Piece of Cloth) with textile engineer Dai Fujiwara, a technologically driven initiative to eliminate waste in the fabrication process. Feeding a single piece of thread into a knitting machine, they produced tube-shaped garments, their size and shape customisable depending on their intended use. No useless fabric was made, and labour-intensive cutting and sewing processes integral in normal fashion production were virtually eliminated.

Driven by relentless curiosity for the possibilities within design, Miyake collaborated with craftsmen, textile engineers, and computer scientists alike, harnessing new technological techniques to develop the textiles on which his legacy rests. Despite receiving many awards, including the Kyoto Prize for Lifetime Achievement (2006), Japan’s Order of Culture (2010), and France’s Commandeur of the Lègion d’honneur (2016), Miyake remained grounded in the notion that his achievements are the product of collaborations in and beyond his studio.

In the words of Isamu Noguchi, Miyake’s practice had “more to do with an attitude of warmth and ease – a way of accepting and giving – a generosity that disarms.” Through sustained belief in the power of design, Issey Miyake has bestowed us with a life’s work of innovation. He leaves this world a little more joyful than when he entered it.