Shannon Taggart’s Séance arrived in 2019, the first monograph from the photographer out of Saint Paul, Minnesota. She spoke to Sammi Gale about illuminating the mysterious world of the spiritual.

Shannon Taggart photographs smoke rising up a chimney in a village inn before a séance in 2013. In the resulting image, there is a face in the vapour. Whether you believe in smoke-scrying as divination or pareidolia (the tendency to interpret vague stimulus as something known), it’s all too human to find sense in the senseless. When Taggart first visited Lily Dale, the world’s largest Spiritualist community, she envisioned an eight to ten-image photo story. Little did she realise she would tie up this little story 18 years later with her new 300-page book, Séance.

Image Credit: Shannon Taggart

In an age of Deepfake and Photoshop, you might think there is something old-fashioned about spirit photography, a phrase that conjures images of solemn double exposures on grainy, Victorian carte de visites. But technology and Spiritualism are intimately entwined. If you accept that Shannon Taggart’s disembodied voice is arriving in my laptop via Zoom from three thousand miles away, it’s not such an imaginative leap to say; a spirit is tapping Morse code on the wall. So it went in the 19th century, with the invention of the telephone, the telegraph, and the photograph — as well as discoveries in physics that suggested the universe was governed by invisible energy forces. ‘People know that photography can trick,’ Taggart says, ‘but it still can inspire belief.’

Spiritualism is having a moment. ‘At least partially,’ Taggart speculates, ‘because of the time we’re in, which is very uncertain. There’s a lot of talk about what people did in the past and how that relates to us. Spiritualism is such an interesting part of history, which has been neglected, not just in photography and art, but also the history of women’s rights, the history of science.’ Indeed, The Gallery of Everything’s current exhibition, The Medium’s Medium, which features Taggart’s work, is symptomatic of a recent curatorial shift attempting to recover 19th and 20th-century Spiritualist art-making for the canon. Critical narratives have focused on feminism, abstraction, and other artistic processes — such as automation — which fed into Modernism. But there’s been disobedience of the spiritual essentiality of the work.

Image Credit: Shannon Taggart

Image Credit: Shannon Taggart

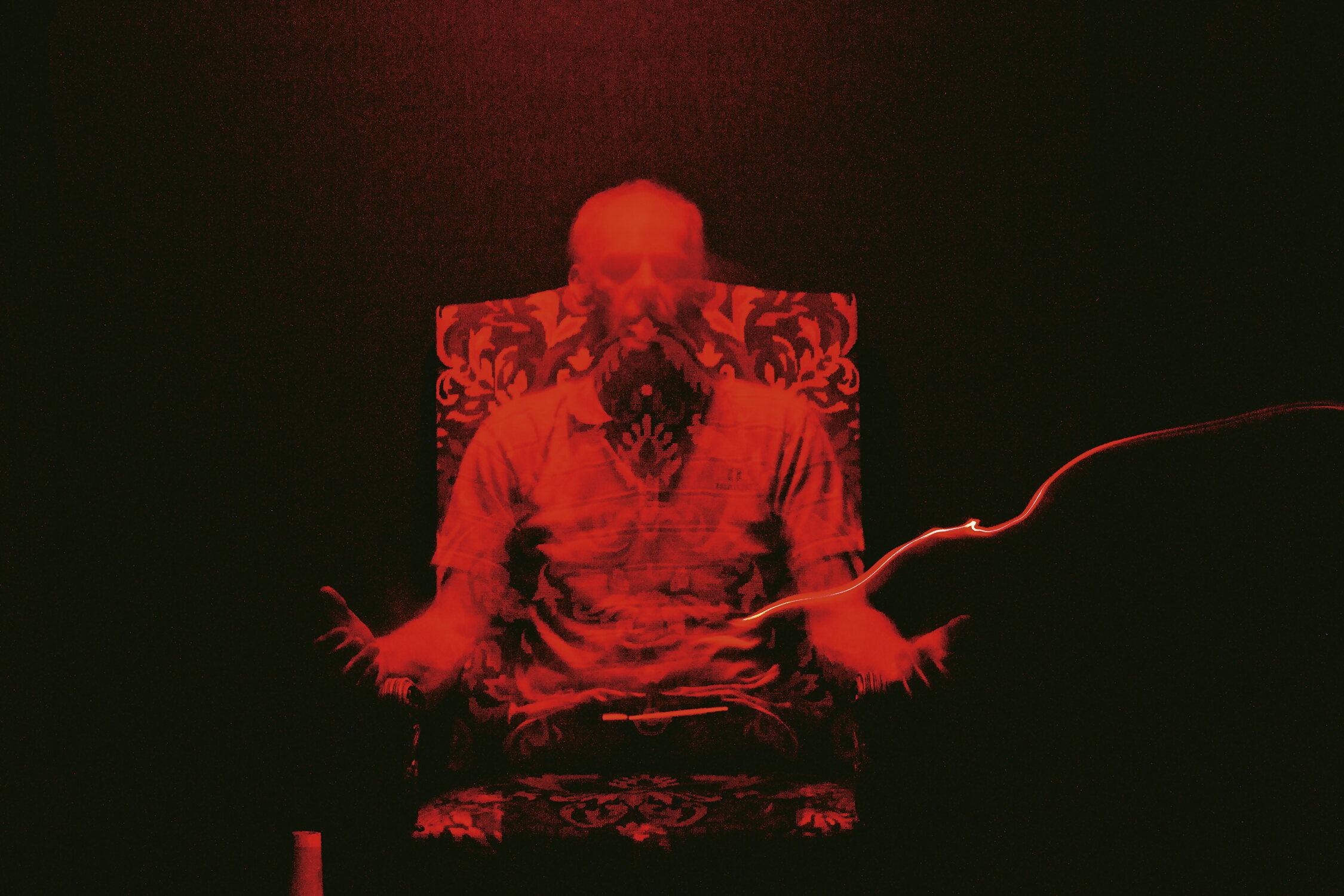

Throughout our talk, Taggart is careful and considered, walking a tightrope and refusing a fixed narrative (sceptic/believer; artist/documentarian). This refusal, and a strong sense of balance, are characteristic of her work, which encourages viewers to experience the material on its own terms. A photo at Gallery of Everything presents warped kitchen utensils on a leather-bound book, signalling us towards an official, unbiased reading: Exhibit A. Another shows a long exposure of a medium in a trance, appearing bright and smudged like someone tried to rub her out of the darkened room. There’s a candid quality to the mise en scène: a video camera on a tripod, the curtains pulled to block out light, a chest of drawers with vases and other domestic clutter.

Taggart’s is an aesthetics of honesty for a subject that has a complicated relationship with deceit. Spiritualism is bound with rationalism: spirits should prove themselves by objective means; however, efforts to substantiate séance phenomena have been fraught with fraud accusations. According to Taggart, ‘this interplay between true and false is rampant in every aspect of Spiritualism.’ For instance, sometimes her Spiritualist friends are shocked to find that she has included, in their opinion, ‘fake mediums.’ When she started the series, Taggart thought she might find a pure True or False. Over time, her aim shifted. ‘The more I embraced the ambiguity, the more interesting the project became,’ she says.

Image Credit: Shannon Taggart

Image Credit: Shannon Taggart

Taggart’s breakthrough proved to be ‘a few happy accidents with the camera’. She gives an example from the book: ‘a woman’s face doubled in the exact way that everybody in the séance was describing they were seeing clairvoyantly, and I just accidentally made that picture.’ She realised that the ‘photographic anomaly’ might be the answer. To photograph the invisible, she would ’hand over the question to the process’, embracing automation and chance: ‘I guess the photographic synchronicity became my Holy Grail.’ Camera mishaps spoke to the reality of the situation in a way that Taggart couldn’t have anticipated. ‘Often the picture you take isn’t the one you intended,’ she says. ‘Confusing who or what is the medium is a very interesting aspect.’

Taggart says that her Spiritualist friends sometimes tell her, ‘Oh, you’re a medium, you’re just using a camera for your mediumship.’ While she would shrug off the label, Séance is for sceptics and believers alike: a work that takes us out of this world so that we might see it more clearly. Immaculately written, true to Taggart’s tightrope style, the book is brimming with horror, humour, and humanity. After viewing, Taggart’s images sneak into the mind, build and become malleable, like ectoplasm. A camera works less like a human eye than you might think. And what your eyes see is not the same as what is seen through someone else’s.