A mirror would normally suffice. Glimpsing yourself in the morning, red eyed, bed haired, before and after the shower, maybe you’d send a photo of your face with some text floating about to an acquaintance, finally before slumber, with inexplicably beautiful hair that’s completely useless now. What would compel you to have it painted?

Subjected to the dissociated glare of someone with a brush, anxiously wondering what you’ll permanently appear as, portraiture can be a nerve-wracking business. Before photography, a portrait represented a critical way of means for an artist, working on commission from the landed, the wealthy, and royalty. They had to flatter, make the subject look younger, remove warts, fat, birthmarks, double chins in order to stay working as an artist. The camera liberated all that; portraiture broke free. Conventions leapt out the window, friends began to be depicted as ugly, their figures fragmented, torn, Picasso painted Gertrude Stein in a way she hated, telling him it looked nothing like her, “it will”, came his typically mythic reply.

Crucially, here, artists can paint the portrait of whoever they want, in an attempt to reveal their essence, and having these artists paint you however they want can be an honour worth shelling out for. In this article, I’m wanting to explore those who have had their portrait painted in record numbers, as well as artists who have mercilessly painted the same subject in a singular series. What does it do to the painted, to the sense of self?

It means something, to be painted. It can be an expression of permanent status, of cultural publicity. If you found yourself crawling Parisian nightlife between 1933 and 1960 with a penchant for cabaret, you were likely to stumble across La Vie Parisienne. On walking in, you would hear a voice of such huskiness that Jean Cocteau described as issuing from the singer’s sex. It was Suzy Solidor, owner of the bar, singer of explicit lesbian desire, surrounded by portraits of herself.

ArrayBorn in St Malo, Brittany, Suzy Solidor lived her life following ‘solidorian’ principles, operating in the world as it was presented to her, making it work for her. She was beautifully androgynous and hyper aware of her image – adept at turning her body into a commodity. Her first lover, antiquarian Yvonne de Bremond D’ars, began the portrait push, invested in making Solidor an icon. She was a singer, actress, the first woman to own a nightclub in Paris. The portraits take painted, sculpted, photographed form, a great advertisement for the artists who painted them, as well as being an expression of cultural success for their subject. Stuck by the toilets or sold, the portraits she didn’t like did not enjoy prominence in her bar or life.

Her solidorian principles meant that she kept the bar open during the occupation and it became a popular haunt for Nazis, meaning she had to leave Paris in 1946, returned in 1954, before leaving in 1960 for the southern town of Cagnes-Sur-Mer and establishing an antique store and cabaret. In the second installment at Paris, Francis Bacon painted Solidor’s portrait, using the commission to pay off a gambling debt. Solidor hated the picture, eventually selling it in 1970, before Bacon bought it back four years later and destroyed it.

Francis Bacon, Solidor

At her last cabaret, larger, older, cross dressing and demanding to be called The Admiral, she would perform in the middle of her two hundred and twenty four portraits; they all feature her long, shapely, broad shouldered body, sheer blonde bob. The quality wanes hugely. There are good portraits by Tamara De Lempika, Man Ray, Cocteau, dubious portraits by Francis Picabia, awful portraits by lesser known artists. Naive, poor quality paintings of a face, serving only to put a larger number on a collection. There is a clear narcissism that permeates many of the paintings, a desire to be as painted as possible, to solidify a position as ‘the most painted woman in the world’, a title which is broadly unquestioned.

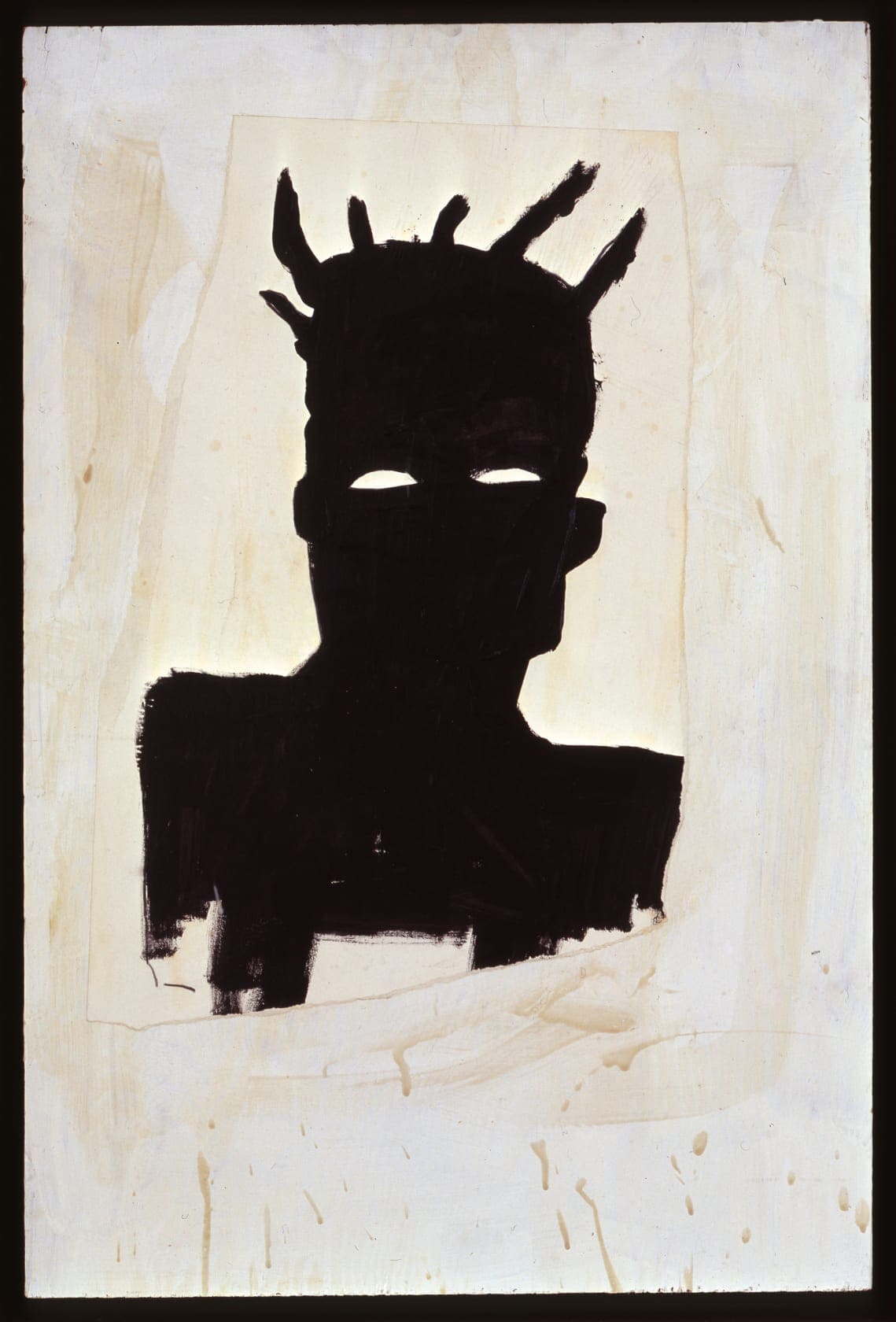

Self-portrait, Jean-Michel Basquiat

One day around 1980, the British pop artist Antony Donaldson was in Paris, attending a dinner with fashion designer Emmanuelle Khanh. A woman called Joan Quinn was there, discussing an idea she had of asking many artists to do her portrait. By chance, Antony had that morning purchased a book on Solidor at a flea market, which Joan took an immediate interest in. Antony gave her the book, Joan’s collection of portraits began to rocket upwards.

Heir to this painted throne, Joan Quinn is a key patron of LA’s art scene, former West Coast editor of Interview, former society editor of the LA Herald Examiner, she has been a central figure in the art world over there since its incarnation in the mid fifties. The collection is a who’s who of great modern and contemporary artists, especially if they live in California. Hockney, Basquiat, Warhol, Mapplethorpe, the list goes on until the count reaches 192*. It is a collection of dizzyingly high quality, owing to the love and affection that the artists feel for her.

Daughter of legendary race promoter J.C. Agajanian, Joan met a young Billy Al Bengston at her father’s speedway, who introduced her to the Ferus Gallery crowd, including Ed Keinholz, Ed Moses, Robert Alexander, which then led her to Frank Gehry, Ed Ruscha, and then any LA artist’s name you can think of, or google. The scene was extremely small in those early days, and any support was warmly appreciated, adding credo to a scene that struggled to escape New York’s shadow. Along with her husband Jack, Joan befriended, supported and proudly exhibited the great and true artists of the avant-garde community, hosting seminal salons in their Beverly Hills home, welcoming and embracing artists as family.

Untitled, Ed Moses

Her portraits began in 1953, when Joan was 16, with a fabulous John Carr painting and, encouraged by Warhol to develop a collection of portraits and start a TV programme (which she did, the cable show The Joan Quinn Profiles has been showcasing West Coast talent since 1993), she has accumulated so many that her house cannot display them all, there is not enough wall space to hang the myriad pictures of her visage. No matter, her love for art is stronger than her vanity, and as such she never interferes in any artists’ interpretation.

This results in a portrait collection of such variety, Joan done in sticks, rendered as an Interview magazine stand, as a pisces sculpture, painted onto a door, in smashed glass, as a xerox collage, tiny, huge, vibrant, eclectic, ugly, flattering. When artists fell on hard times and approached her for support, she would offer them a commission in return for a portrait. A unique aspect of this collection is that many of the artists have never made a portrait before or since depicting Joan. Made for her birthday, Ruscha’s characteristically detached J. Q. painted on two separate tiny bits of wood pushes portraiture past its limit.

Joan feels like a bowl of fruit after all these different renditions, a still life composition that exists for artists to use in whichever way they please. It is a great flattery, but it must do strange things to your sense of self – what am I? Who Is Joan Quinn? as one exhibition of her portraits is titled. Many articles and some artists say that it is impossible to know, but the answer seems simple – an endlessly generous, ambitious, warm icon of Los Angeles, with total dedication to the arts. It’s not about her, it’s about the artists. This has been the inspiration and motivation for some 192 artists to create her portrait.

ArrayAppearing on The Joan Quinn Profiles in 1994, Huguette Caland detailed the moment she decided to start painting LA artist Ed Moses, seeing him at an exhibition opening in Paris, not speaking to him, and beginning at full pelt to paint his portrait, in a series that would exceed one hundred pictures. Artist prowling after sitter, without his knowledge, the memory of his face, then his personality after she moved to LA.

He saw them two years before the JQ show and was so horrified that he told his gallery to never show Caland’s work, or else he would leave. This is a subject we have covered before, but it is an important step both structurally and ideologically for this article to include this case. An artist painting after a visual accident, propelled to paint a stranger’s face, treading the boundary between abstraction and representation, so bizarrely accurate and enamoured that it may have hindered Caland’s career to have painted them, she was never represented by an LA gallery in her years there. The painted reacted with abrasion, affected, confused.

Twenty-four years later, across the country, across the pond, Chantal Joffe’s marriage was falling apart. At the very beginning of the year, Joffe decided to work on a self-portrait every day until the end of December. There is no gracious absence of unwanted blights, only unwavering commitment to show what is really there, a mirror to what was happening in her life. The visual shifts stem from her position in time and space, harsh winter’s light in London, the pitch black of night, the intense heat of New York, each one unique in their evident displeasure of being looked at, at being seen.

Each of these pictures was painted with the same small mirror, raw, quick, the same face she wakes up to every morning and wishes goodnight to. The same eyes, the same chin, turned slightly sideways towards you, staring straight at you. Once you’ve spent enough time with them, their difference can be admired. They are experimentations and meditations on the form, green sometimes creeps through the cracks of the painted surface, it’s a thrill to see how they morph and change whilst categorically being identical – all self portraits, 2018. Collected, for Joffe, they began to feel like company, a crowd hanging out with her in the studio. Each line of her face became familiar, Joffe started to welcome the same blemishes into the picture, embracing the way that each line of her face would follow into the next work – nice to see you again, wart.

Self-portrait, Chantal Joffe

They were all she could do, and that is all they are. Self portraits are as close as Joffe can get to writing a memoir, so documenting that emotional year through portraiture tells you all you need to know about how she was feeling, what she was going through. You can see it in her eyes, brushstrokes, clothes. They are not meant to flatter, not meant to lie. If the line is to be believed, then there are 365 (or thereabouts) of these pictures in Joffe’s studio. An unflinching inward gaze, recording the moment.

To have your portrait done, then, means a lot. If they’re made for narcissism’s sake, the pictures tell you that. If they’re made for art’s sake, the quality shines through. To be painted so many times (especially without your knowledge) can freak you out, rattle you, lead you to nastiness. To paint yourself mercilessly can be a comfort and a diary. Portraiture has been set free for well over a century, and it is still revealing more and more about how we see each other, ourselves, and the world.

*Correct as of 2011 – Source: Mysterious Objects, Portraits of Joan Quinn.

CORRECTION: The original article incorrectly named Alfred Carr as the first painter of Joan.