Meet the man who captured New York City Disco in the late 70s. Bill Bernstein talks about the differences between clubs, the social significance of the time, and why that moment simply can’t be replicated.

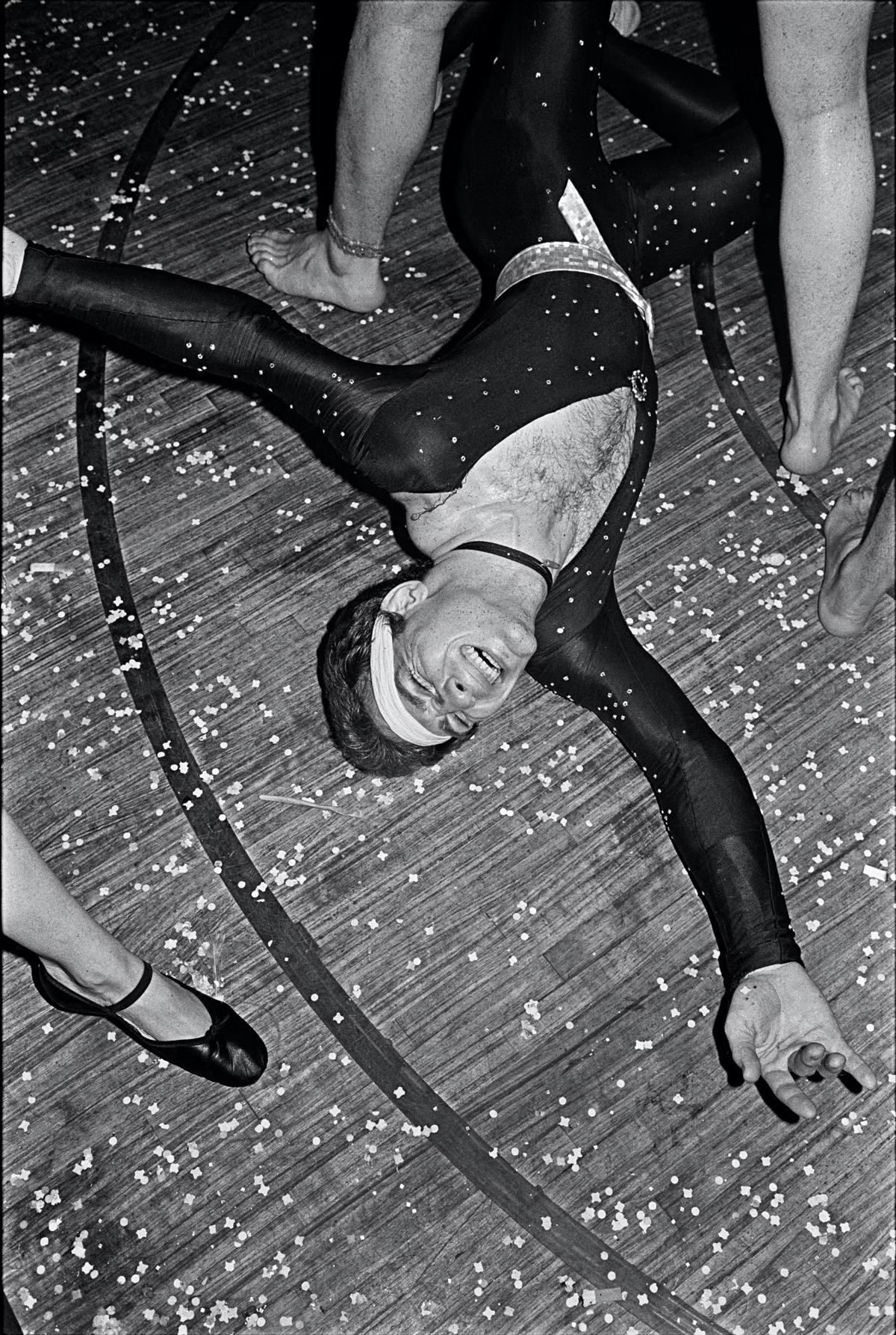

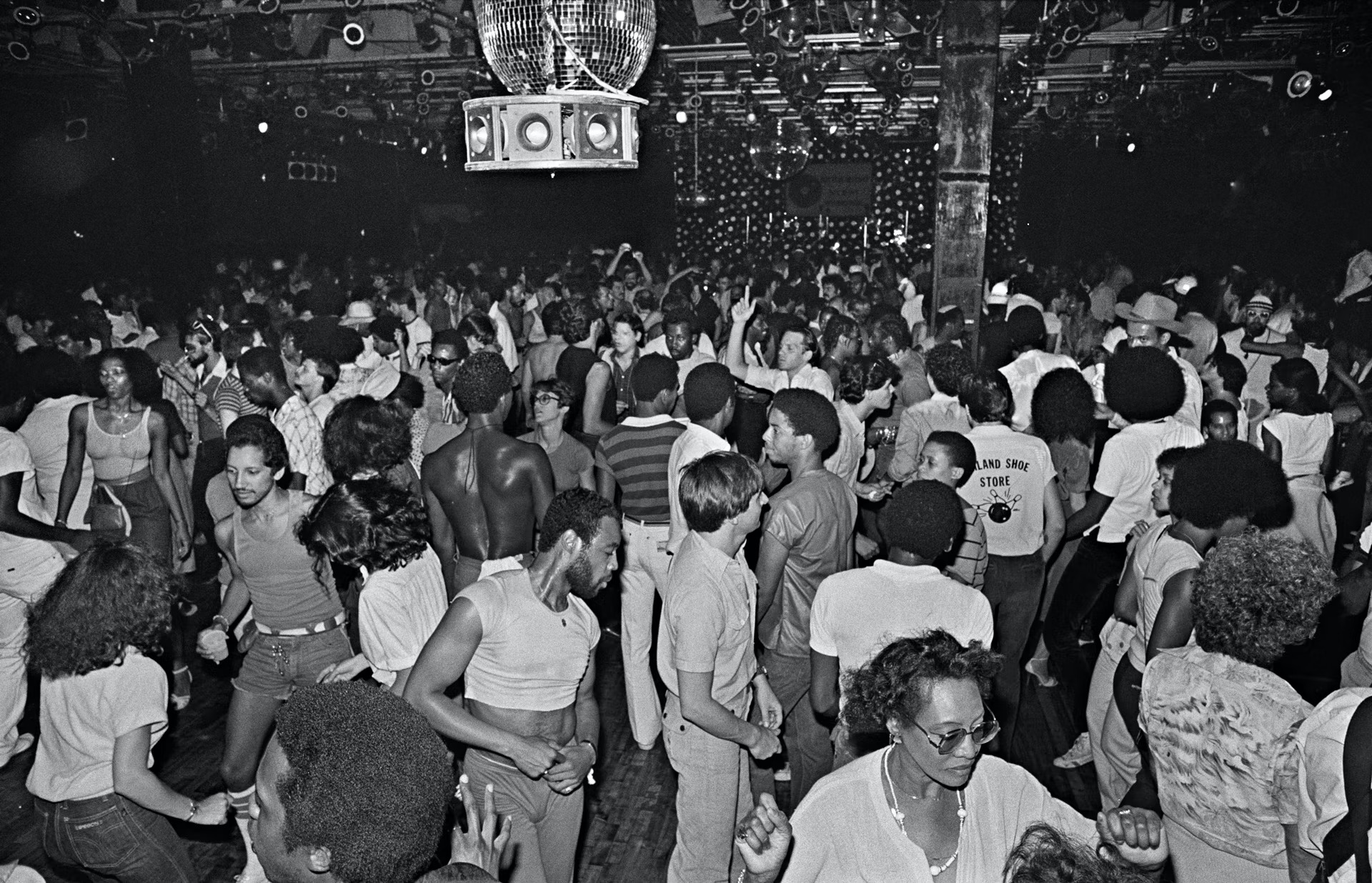

“There was an excitement in the air,” explains Bill Bernstein. “When disco happened, you had all these social movements converging. LGBT next to women’s liberation and civil rights, all partying together on the disco floor. It was so multicultural. That’s what I saw and that’s what was so interesting to me.”

Bernstein didn’t just see it. He documented this fleeting moment – this “flash in the pan” – with photos that for years went largely unseen, living in shoeboxes. Now, they compromise his ongoing London exhibition at Defected Records, and book of the same name, Last Dance.

When I greet Bernstein, he’s flicking through a Keith Haring table book. Haring was a key part of the cultural movement that swept across New York in the early 80s – a movement that Bernstein captured in its infancy, just years prior, at its most carefree and energetic.

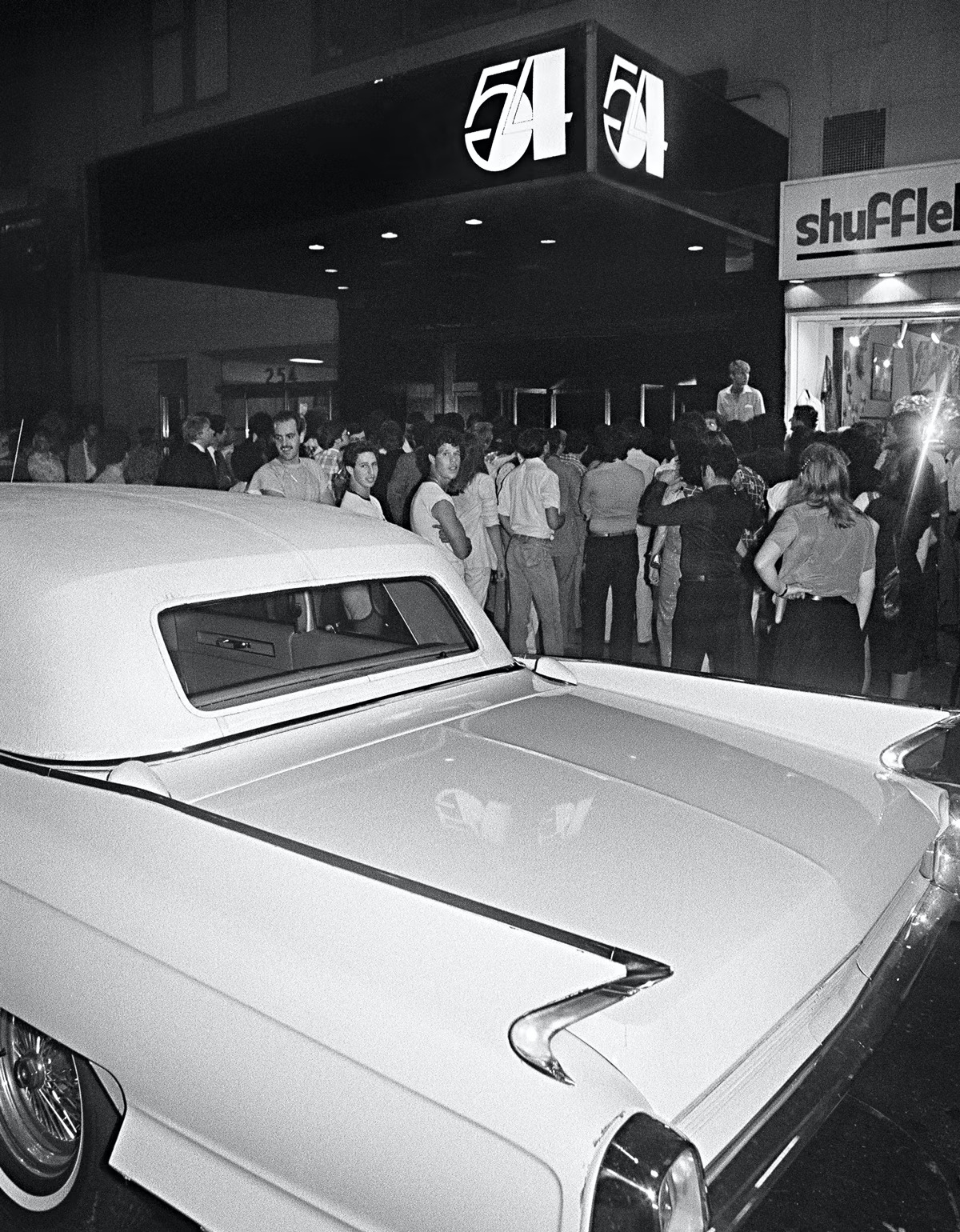

Across infamous venues such as Studio 54, Paradise Garage and the Mudd Club, Bernstein’s work details a point in time increasingly the subject of interest and admiration. A point in time that is also becoming clear could never happen again.

“It feels a little bit like saying, Do you think the Beatles could happen again? It’s happened. So anything that happens now will be compared to that. Before Studio 54, there was nothing like it. I see some clubs today in Brooklyn that try to do the Studio 54 thing, and it feels different. It’s cool, but it feels a little forced. You can’t recreate that energy.

“I just think there was so much else going on, outside of disco, culturally and in the world, set to the backdrop of New York City falling apart. Rents were cheap so artists were attracted to the city. The population was of a certain kind. Then those political movements I talked about before, all meeting under the same tent. It was a perfect storm.”

It wasn’t a storm Bernstein necessarily went looking for. Having studied graphic art and photography at university in Connecticut, he initially wanted to go into graphic design. But after moving to New York City, “doing various jobs here and there”, he decided to become a freelance photographer.

“I started working for The Village Voice in the mid-70s. I was shooting some artists and playwrights in the village and around town. Mostly portraits, which is kind of what I do now, and some street photography. And then I got an assignment one night to go to Studio 54 in 1977. It had only opened a few months before and I was excited to go because I’d heard a lot about it.

View this post on Instagram

“That first night is when I saw the inclusion and I just thought, Wow. I immediately thought of Brassaï, who was the eye of Paris back in the ‘30s. He went down to these clubs and photographed women in tuxedos with their arms around each other – this sort of underground, gender-bending life of Paris. So I thought this was what was going on underground in New York.

“I started going around town to get to the different clubs and each club had its own crowd. Each attracted its different tribe. They were really different, in the experience of the club and the way they were designed. Like Studio 54 was an old studio, with rigging on the roof and the ceiling that could bring down different effects during the course of the night.

“Studio 54 also had an upscale kind of feeling. Everything was very well done. The scenery was really upscale and the sound system was great. The couches were really cool. And they also intentionally tried to get celebrities to come, with special events and press people. Knowing that there were celebrities in there makes the average person want to go in.

“So you needed to dress a certain way. You needed to look a certain way. Steve Rubbell [the owner of Studio 54] would pick people out of the crowd to come in. It was great and it was horrible. It was horrible, because not everyone can get in, but it was great because he was constantly going back and forth between the inside of the club and looking around on the outside and seeing what needed to be included. It wasn’t about just picking one kind of person, it was about making the party inside more perfect. He was really creating the evening.

I wanted to capture the real essence of nightlife.

“But then you had clubs like Paradise Garage, which was a downtown club. People didn’t worry about dressing. They wore workout clothes because they knew they were going to dance all night – from like 11 at night to 12 the next afternoon. So that was a whole different vibe.”

Despite the host of famous faces, they aren’t prevalent in Bernstein’s work.

“I was immediately drawn to the people at the clubs, not the celebrities. The celebrities were always being photographed by paparazzi, and I’d just seen so many horrible pictures of celebrities. If you didn’t know who the person was, it wasn’t a good picture. I wanted to capture the real essence of nightlife.

“The technical stuff was tricky. The clubs are dark. They’re smoky. You’re shooting with a flash. You’re shooting with film. And you’re also shooting people at a party. You’re not posing them. You’re capturing what they’re doing, so it was very, very tricky.”

Bernstein’s first book detailing NYC disco arrived in 1979. “That was more or less a travel guide through New York discos. It was published by Random House and gave information about the door price, dress code, what kind of drinks they served, and just the kind of place it was. It sold about 100 copies, but it was the end of disco. Disco started overly saturating the airwaves and people just got tired of it. It was too commercialised. It kind of died for a number of reasons. Another big one was AIDS. People didn’t want to go out at night.”

Although Bernstein’s disco work drew some attention at the time, for years it lived solely in those shoe boxes. Only in the last few years has it been brought to wider attention. In 2015, it was compiled in a coffee book, titled DISCO. Last Dance launched in November and the first editions sold out by December. His exhibition Glitterbox Presents Last Dance is on display at Defected Records in London, sadly only on display until tomorrow, April 29.