Born in the Persian town of Sarab in 1959, artist Davood Roostaei has observed political struggle and persecution throughout every stage of his life. In 1979, his art studies were violently brought to an end by the Iranian regime, who deemed his work incendiary.

Now living in LA, after a stint in Berlin during the fall of the Soviet Union, his work is popular among the likes of Sir Paul McCartney, Hilary Clinton and Sir Anthony Hopkins – largely as a result of its unique ‘Cryptorealist’ style.

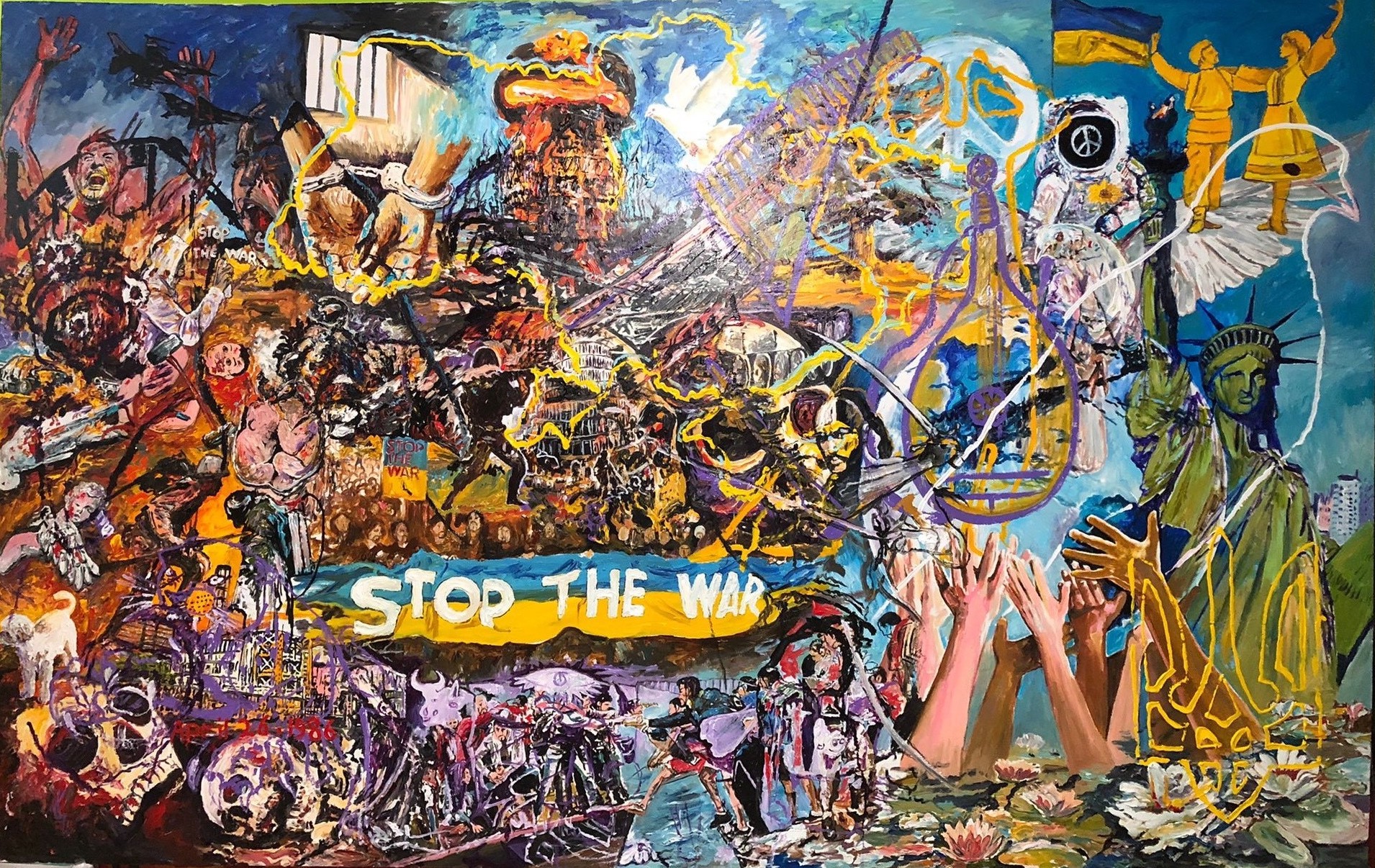

Yet despite the heady nature of his current clientele, Davood is always eager to reflect the plight that he’s observed throughout much of his life in his work. As such, he is currently finishing his latest piece, ‘Imagine – 2022’; this large, 8 x 12 feet painting is estimated to sell for around $1million. All proceeds from the sale will go toward relief efforts in the world’s current global tragedy in Ukraine.

Here’s Davood, in his own words.

Your art was deemed subversive by the Iranian regime in the late ‘70s, disrupting your art studies as a young man. Could you explain what happened in that situation and what it was like for you?

Those were certainly some very turbulent times. The Iranian revolution happened in 1979 and it disrupted my art studies quite violently. At that time, I was going to the Faculty of Fine Arts in Tehran. I then decided to become politically active and did large graffiti art against the regime which eventually got me arrested.

And you were thrown in jail for two years. Could you describe that experience?

It was certainly a very horrific experience. I was thrown into jail in 1981 for two years. But in many ways, it taught me to look inside as an artist and outside as a human being. It had a lasting impact on my perception of life, and my path as an artist.

Davood Roostaei, Activating the Void, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 48 in. © Davood Roostaei.

What was it about graffiti as a medium that allowed you to express your disapproval of the regime at the time?

Well, the nice thing about graffiti as a medium is that you can capture the attention of many thousands of people very quickly – especially in those days before the internet. Political commentary through any type of art can evoke an emotional response, which can be very effective at getting a message across, especially in oppressive political climates.

You sought asylum in Germany after your release. What was that like and how did your artistry develop there?

I gained asylum in Germany in 1984. And that’s when life began again as an artist. It felt like a fresh start, and it truly was.

In Germany I continued my art studies; first at the Kunst fur Hochschule in Cologne and later at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg. The freedom I found there allowed me to experiment and find my own path creatively. Out of this opportunity, I created Cryptorealism.

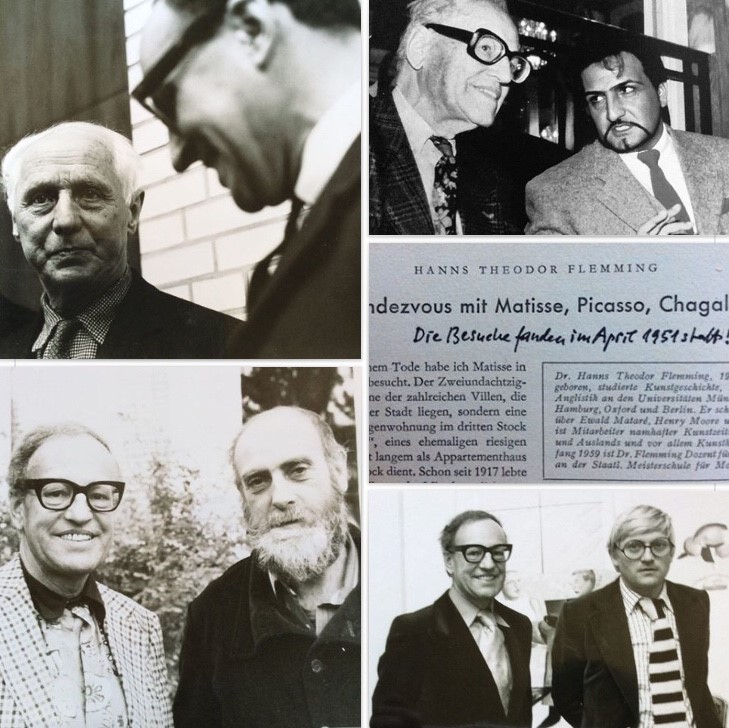

A particularly significant person for you to meet in Germany, it seems, was the art historian Hanns Theodore Flemming. Who was he and what impact did meeting him have on you?

I met Hanns Theodore Flemming in 1986, he had a great impact on my work. Flemming was an incredibly knowledgeable art historian. He spent a great deal of time meeting with many important artists of the twentieth century such as Picasso, Matisse, Chagall, Nolde, and Dali; and had talks with Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Otto Dix, Eduard Bargheer, David Hockney, Andy Warhol and many other great artists.

Hanns Theodore Flemming with Max Ernst, Hundertwasser, David Hockney, and Davood Roostaei.

He also wrote extensively about their works. As a result, he had a very good, in-depth understanding of the progression of art, which I was able to benefit from.

I spent nearly twenty years meeting with Flemming on almost a weekly basis and he became one of my main early biographers and he wrote extensively about my work. He was one of the first people who really appreciated Cryptorealism; and in many ways, I think he fell in love with it, dedicating the last twenty years of his life to writing about it – which I am very grateful for.

How do you define ‘Cryptorealism’ and why did you adopt it as an art form?

Cryptorealism is an expression of hidden meaning, revealed through layered imagery, which requires active participation by the observer. I created it out of a sense of need for a method by which I could express myself fully and allow for a multitude of perspectives to come to life simultaneously on the canvas. Initially it was referred to as abstract Surrealism, though in 1990 it was given the name Cryptorealism.

Cryptorealism is derived from the Greek “cryptos”, meaning hidden or secretive, which implies a fine sense of perception from the viewer. It’s all about making the viewer look beyond what is readily perceptible in both art and in life. In many ways I play a game of visual hide and seek with the viewer in my work.

I overlay different levels of images, meaning upon meaning, then I finish it off with intentional and controlled throwing of colours. There is more than meets the eye at first glance when looking at my work, the various motifs reveal themselves the longer you examine a Cryptorealistic painting.

If ‘Cryptorealism’ is the construction of “meaning upon meaning,” layer upon layer, does your perspective on your own work therefore change throughout its production? What have you observed happens to your relation to your work as you add layer upon layer?

I can often see the painting in my mind, then I go to the canvas to execute it. The study drawings often depict the main themes, which then transform, layer by layer, image upon image, in a web of meaning that may span various topics and timelines, though are connected to reveal a clear meaning or message.

Davood Roostaei, A Cryptic Message, 1990, 45 x 55 in, oil & acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Shophet collection. © Davood Roostaei.

Each layer may appear to change the trajectory of a piece, but in my vision each layer is connected to the one before and after. In this way, it is intentional to inspire the viewer to look beyond what is readily perceptible and be able to make their own connections through the varied images of a given piece.

As a work progresses, some dominant images fade into the background, while others emerge. The effects of this are magnified by the deliberate use of colour splashed upon it to finish a Cryptorealistic painting. I have a very visceral connection with my work, each piece is a part of me, and I am grateful to have this great means of self-expression.

You haven’t used a paintbrush since 1986, using your fingers to paint and produce your works instead. Why?

It enables me to connect more viscerally with my work without the technical and intellectual conventions. I always say, “as ‘reality’ couldn’t speak to the complexities of the modern world, the brush couldn’t do what I needed it to do”. In a way, I can put so much more of myself into each work both intellectually and figuratively.

Davood Roostaei, Glasnost, 1988. © Davood Roostaei.

You lived in Germany during a time of the Soviet Union. How much did politics inspire your work whilst you lived there? Are there any examples of your work that specifically comment on the social politics you observed at the time?

Yes, politics certainly had a great influence on my work in those years. I did a series of paintings about the collapse of the now defunct Soviet Union and also the collapse of the Berlin Wall many years prior to these actual events taking place. In many ways predicting what was to happen.

For example, the painting titled, ‘Glasnost’, was painted in 1988. I painted it three years before the collapse of the Soviet Union, depicting the troubles and the fact that the time for communism was running out.

You moved to Los Angeles in 2000. What drew you there?

I always loved the vibe and energy of Los Angeles. I felt like it would also be a place of greater freedom to live the dreamlife with the sun shining all the time. LA also has a wonderful art scene, which I was always excited by.

Davood Roostaei, Imagine, 2022, 96 x 144 in. (Unfinished/painting in progress) © Davood Roostaei.

You’re currently painting a large, monumental piece to raise $1 million for humanitarian efforts in Ukraine. What was the moment that prompted you to do this?

As someone who has experienced political injustice and war, it always affects me deeply to see others experiencing the same thing. I have lived through both a revolution and war, I know how horrifying it really can be. And therefore, I felt like I had to do something about it, and decided to paint this piece titled, ‘Imagine – 2022’. It measures 8 x 12 feet, and it is both a mediation on peace and a call for it.

Has mankind progressed, in your view, or do we merely repeat history?

We have progressed in many ways, but yes, I would say history does tend to repeat similar problems in new landscapes. However, I continue to be optimistic regarding the resilience of humanity and our ability to persevere and take care of each other. While history repeats, we also seem to learn a little more each time it does.

Davood Roostaei, Technology Vs. Technology, 2021, 48 x 60 in, acrylic on canvas. © Davood Roostaei.

You have a number of notable collectors worldwide now, including Paul McCartney and Hilary Clinton. What do you think the young Davood Roostaei – the one whose studies were disrupted as a result of the Iranian regime – would make of where you are now as an artist?

I have much to be grateful for and I am humbled by the continued support of all of my collectors. In some ways, I still feel I am the young me, though I would be mistaken to overlook the various challenges I’ve faced, as well as the accomplishments, and how they have shaped me into the man and the artist I am today. I am very grateful for all of it, and as long as I am able to continue to paint and do what I love, I think the young Davood would be very pleased.