Above: Red Hot Chili Peppers, De Effenaar, Eindhoven 1988

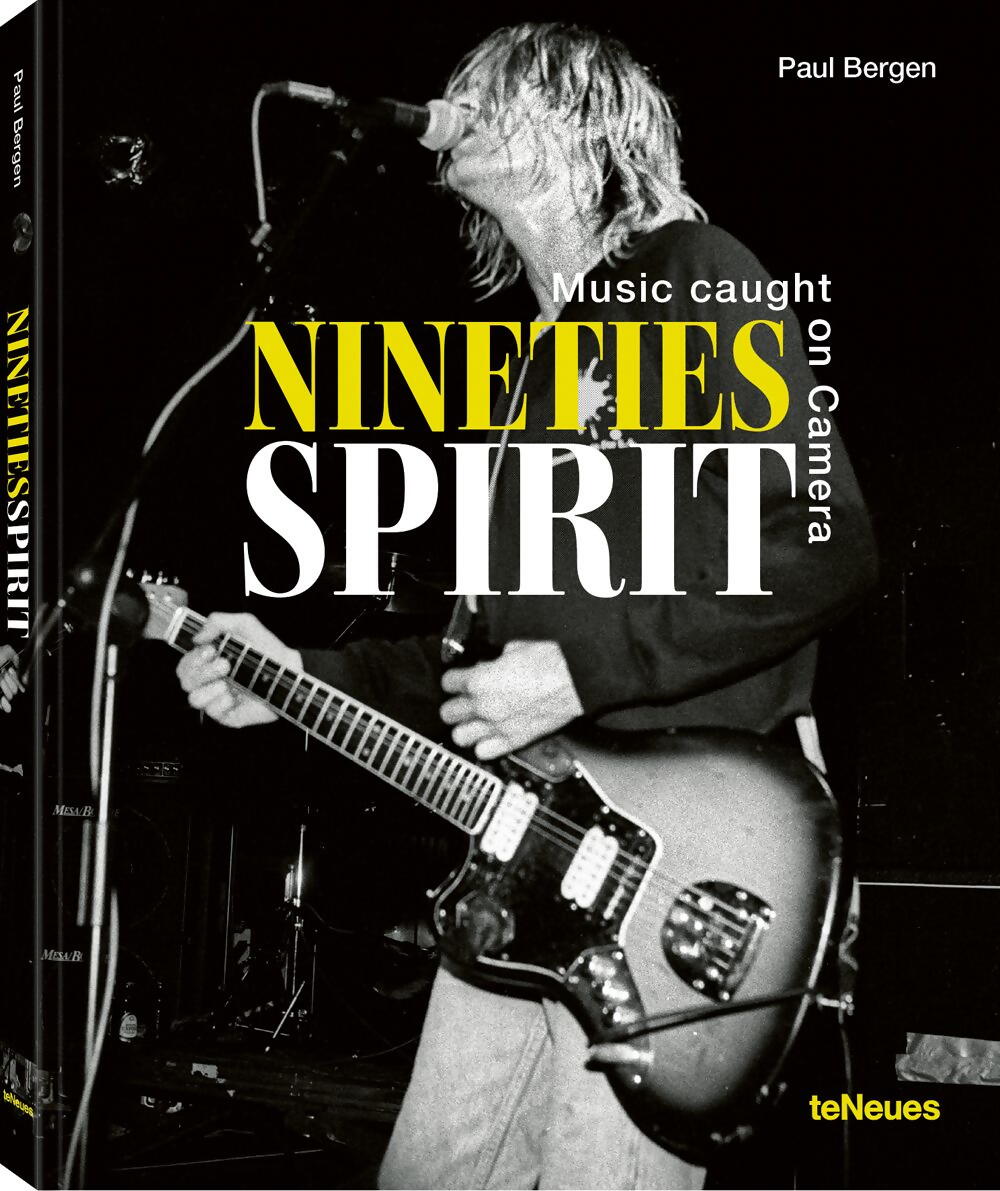

There’s no artist worth capturing on camera from the 1990s that Paul Bergen didn’t take his lens to. Any act that emerged, and any legacy bands reinventing themselves or rooting themselves more firmly on their thrones, are presented beautifully amongst the pages of Mr Bergen’s enormous tome, Nineties Spirit. Accompanying Paul’s photographs are the words of his friend and ever-present music journalist Leo Blokhuis.

Nirvana, Batschkapp, Frankfurt 1991 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

Good afternoon, Paul. Thanks for taking the time to speak to us. What do you miss most about the 1990s and this part of your career?

I miss taking pictures without rules or obligations. In the large venues, the first three songs were generally allowed to be photographed, but in the smaller venues, you could choose to shoot the entire concert. You could, as it were, work towards the ultimate moment.

That’s changed considerably today. Fortunately, you can still work from the photo pit at most concerts, but it happens more and more often that the photographers are positioned at a distance. As a result, it has become increasingly difficult to distinguish yourself by taking a unique photo.

Things have changed quite a bit with the invention of social media, and there are several artists for whom photographers are no longer invited to take their pictures. Add to that the contracts which need to be signed, and it’s become much less fun. Because of that, you can understand what I cherish from the first 20 years of my musical career.

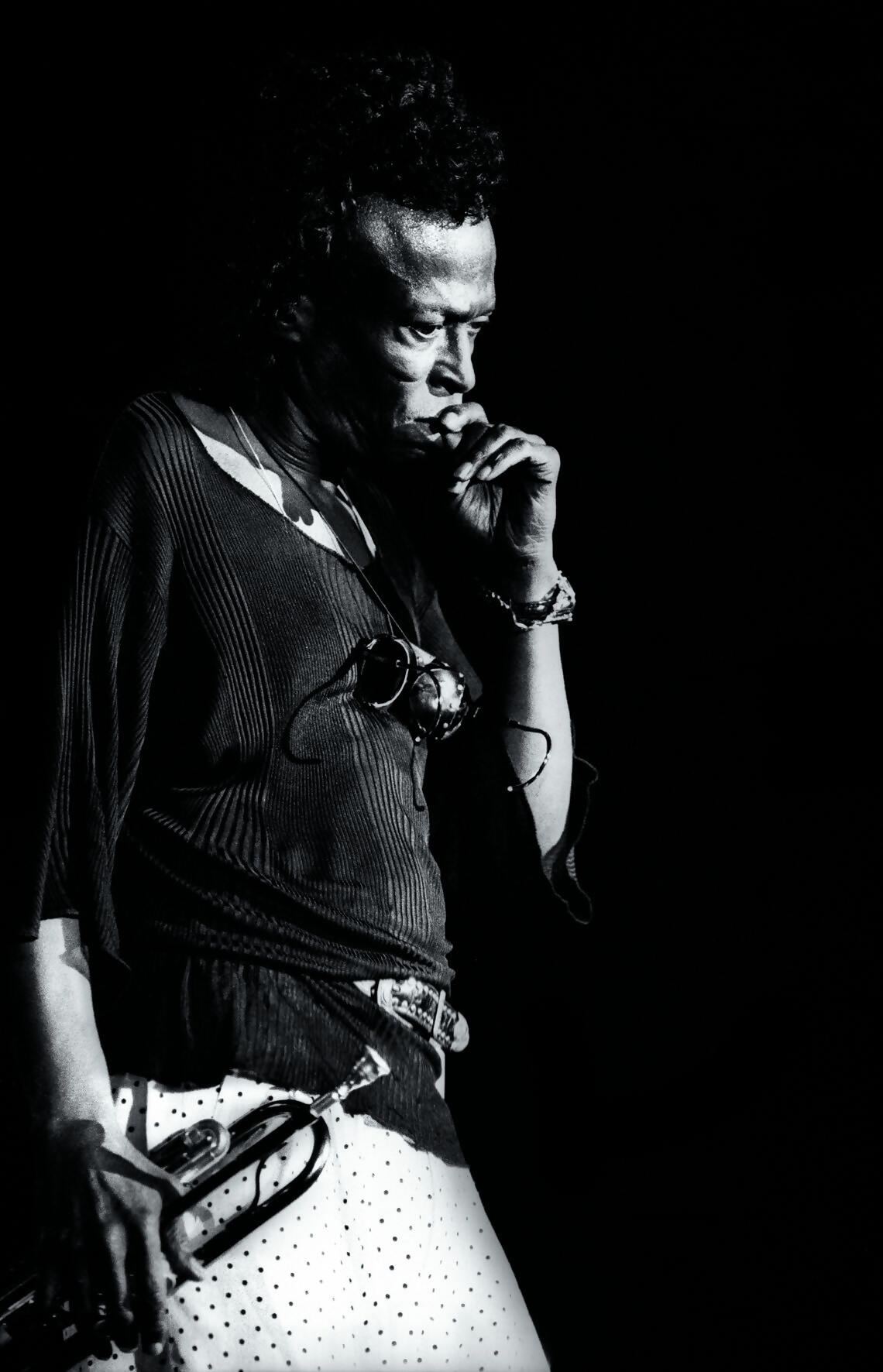

Miles Davis North Sea Jazz Festival, The Hague 1991 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

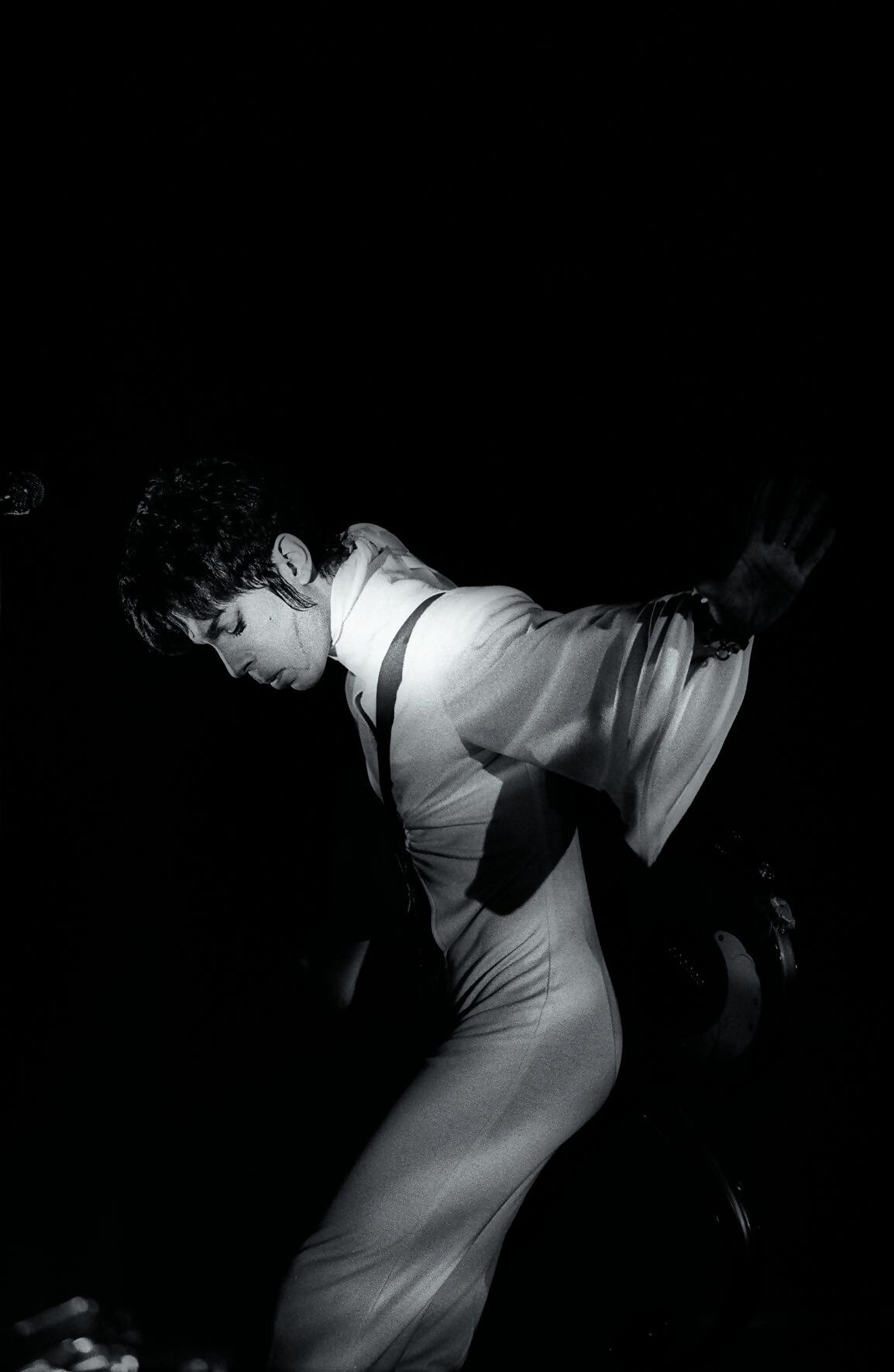

Prince, Brabanthallen, Den Bosch 1995 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

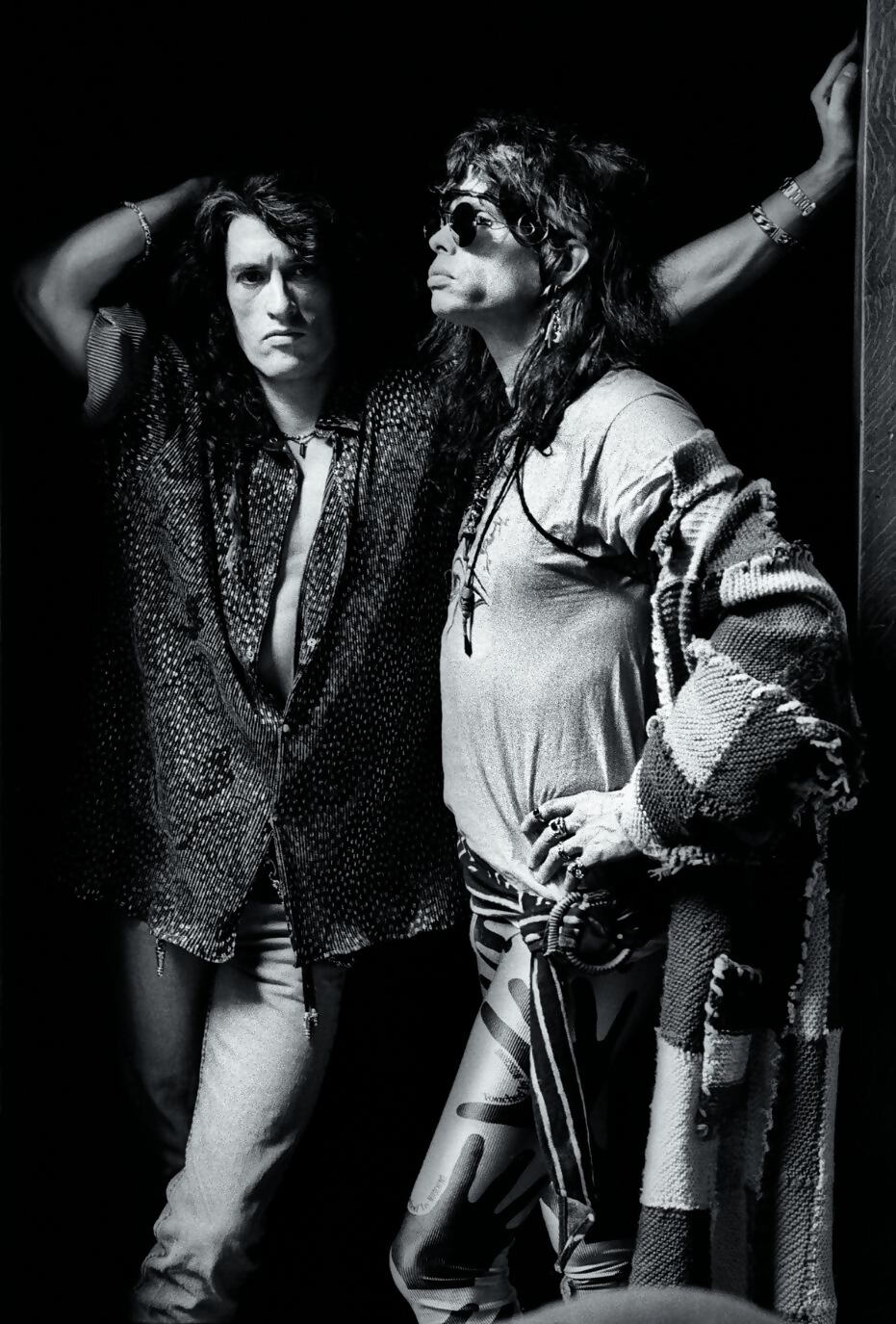

Aerosmith, Amsterdam 1993 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

What are your thoughts on Woodstock 99? Many see it as symbolic of the decline in optimism that Woodstock typified. Were you there? Was the ensuing carnage unique, or are Netflix viewers simply watching the unfolding events of a regular hard rock/nu-metal festival?

I wasn’t there, but I read about it and saw it on TV. Woodstock ‘99 was quickly described as ‘the day the music died’ or ‘the day the 90s disappeared’. The 1990s had a reputation as a positive period, but according to many music journalists, that positive bubble burst in the chaos and violence of Woodstock ’99.

READ MORE: Denis O’Regan | The 80s’ most prolific tour photographer

Everything that could go wrong went wrong: the extreme heat, exceptionally high prices of food and drink, poor security, rough and aggressive music, and groups of horny, violent men who scoured the festival grounds. Over the years, many factors have been blamed for the outbreak of violence, but there’s no one reason. In any case, we can speak of the festival as a black page in the history of the 1990s.

Daft Punk, Amsterdam 1997 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

David Bowie, Vorst Nationaal, Brussels 1996 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

Mary J. Blige, Amsterdam 1999 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

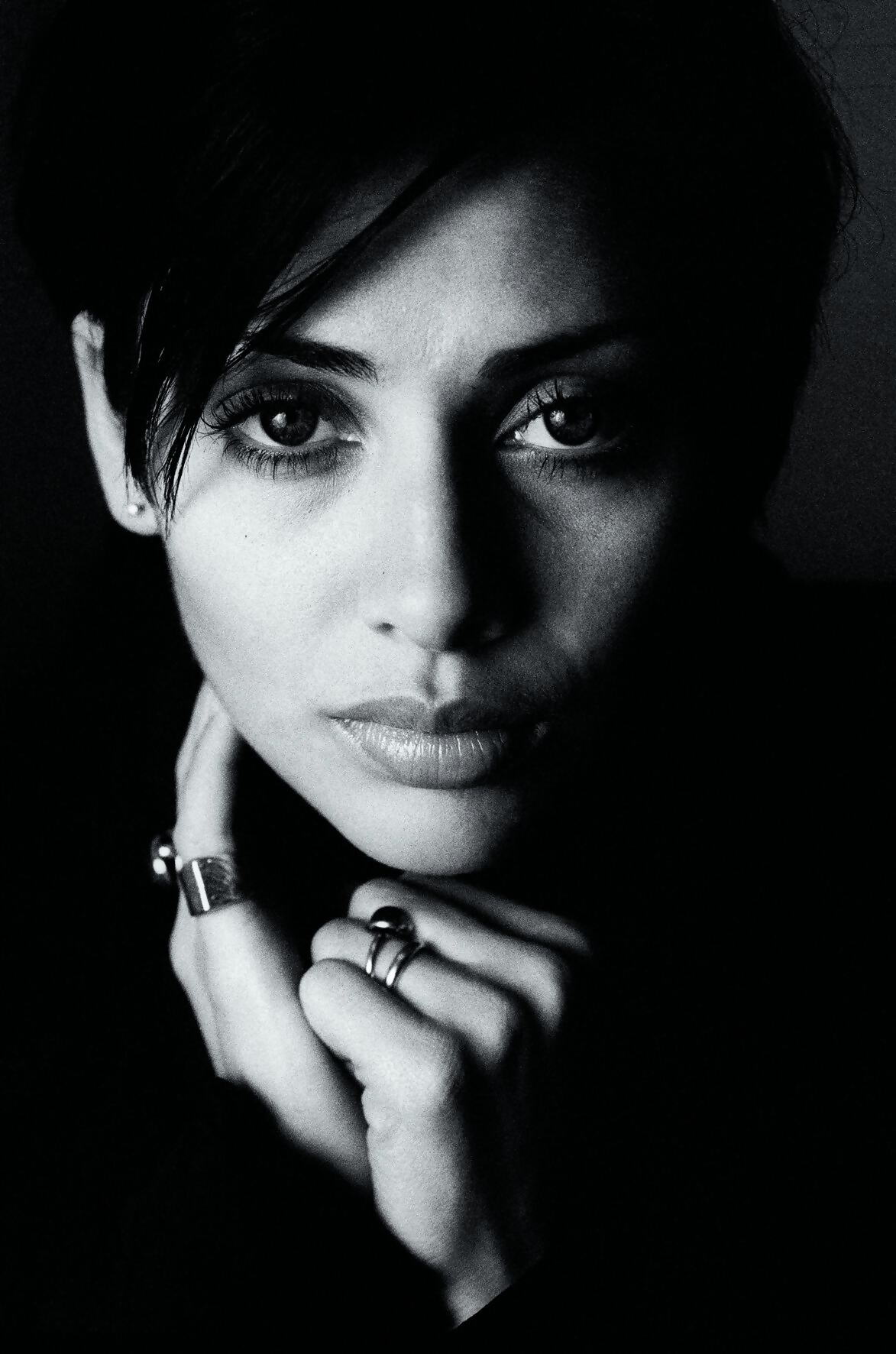

Nathalie Imbruglia, Amsterdam 1998 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

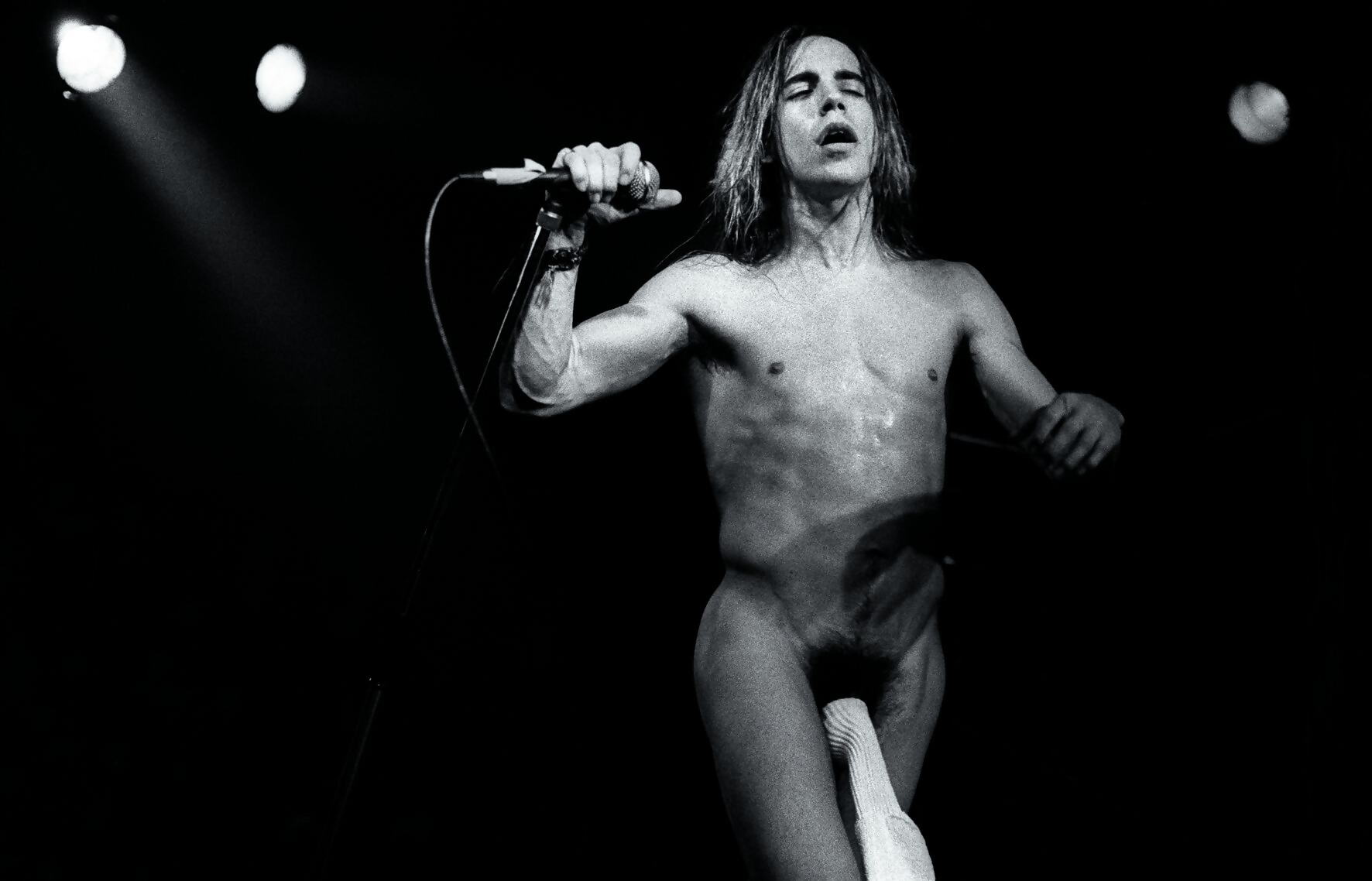

Iggy Pop, Beach Rock, Scheveningen 1994 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

Do we edify these people as demigods? Is this healthy? Throughout your book, the mystique around these famous faces is almost like idols worshipped centuries ago.

Many fans regard musicians as demigods because of the music they make or their rockstar attitude. When one becomes famous, people start to look up to you and react differently; everything you do is under a magnifying glass.

But celebrity adoration is human nature, and sometimes we crave it. Sportsmen, movie stars, and even politicians are often idolised. A simple song can lead to adoration. I don’t adore anyone. I respect them, yes, but that’s it.

READ MORE: Mick Rock | The man who shot the 70’s

Honestly, I never feel like I’m photographing a demigod during a concert or a photo session. I don’t think most of the musicians feel that way, either. They feel pressure from the outside because they have to make an even better album than before, and many artists may also have stage stress, but they’re usually grounded during the shoots.

Nineties Spirit – Music Caught on Camera by Paul Bergen

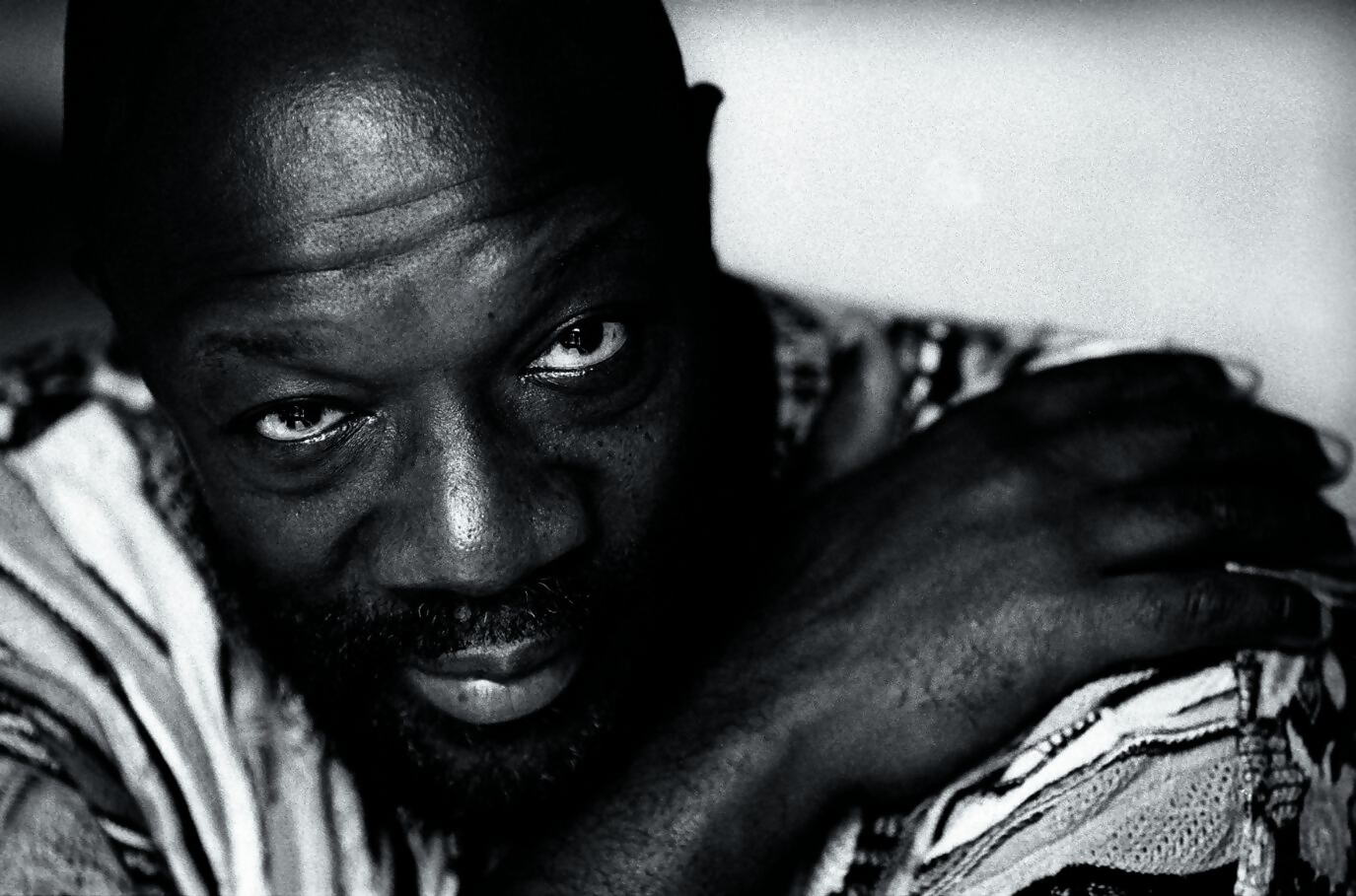

Isaac Hayes, Amsterdam 1995 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

U2, Goffertpark, Nijmegen 1993 (Credit: Paul Bergen)

What are your three decade-defining albums from the era?

Ten by Pearl Jam, Melon Collie and the Infinite Sadness by Smashing Pumpkins, and (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? by Oasis.

What’s the best music documentary made about the decade?

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck (2015).

Nineties Spirit by Paul Bergen, published by teNeues, is available now at Waterstones.